Journal of Financial Planning: December 2022

Executive Summary

- The current study is a replication and extension of the early work of Sharpe et al. (2007). They found strong empirical support for financial life planning in fostering trust and commitment in the planner–client relationship.

- To expand on Sharpe et al. (2007), the study at hand provides an in-depth exploration of the theory of trust and commitment developed by Morgan and Hunt (1994) with a focus on the antecedents to the formation of commitment and trust from a client’s perception.

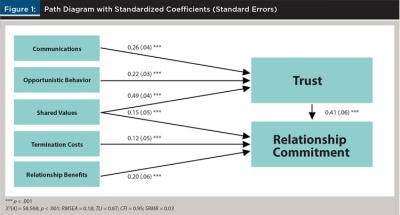

- Structural equation modeling (SEM) results support the theoretical model. Specifically, that trust and commitment are built by the following antecedents: (1) communication abilities, (2) an absence of opportunistic behavior, (3) perceived relationship benefits, (4) the costs of terminating the relationship, and (5) shared values.

- These results suggest that technical skills alone, such as generating high investment returns, may not be sufficient to build client trust and commitment and provide continued financial life planning support.

Megan McCoy, Ph.D., LMFT, AFC, CFT-I, is an assistant professor in the personal financial planning program at Kansas State University. Her research focuses on financial therapy and has been published in top-tier human development and family science, marriage and family therapy, and financial journals. Dr. McCoy volunteers for the Financial Therapy Association Board of Directors and serves as the co-editor of the Financial Planning Review.

Ives Machiz, CFP®, is a doctoral student in Kansas State University’s personal financial planning program. Ives is also an instructor at Kansas State. Ives practiced as a fee-only financial planner for 22 years. Ives earned his B.S. degrees in accounting and in computer science and his M.B.A. from Arizona State University. Ives’s research agenda focuses on the relationship between financial education and financial health.

Josh Harris, CFP®, AFC, is a doctoral student in Kansas State University’s personal financial planning program. Josh is a visiting professor at Wofford College. He received his B.A. from Wofford College and his M.B.A. from the University of South Carolina. He is pursuing research in family financial socialization, financial therapy, and professional ethics.

Christina Lynn, CFP®, AFC, CDFA, is a wealth management consultant as well as an instructor of wealth management at Columbia University. She is a doctoral candidate in personal financial planning at Kansas State University, with research interests in behavioral finance, divorce finances, and digital assets.

Derek Lawson, Ph.D., CFP®, is an assistant professor of personal financial planning at Kansas State University and a financial planner at Priority Financial Partners, based in Durango, CO. His research is practitioner-focused, allowing him to combine his past and present experience as a financial planner with his research interests. Lawson’s research focuses on relationship dynamics, physiological stressors, financial therapy, behavioral finance, and consumption decisions, with a primary focus on younger adults not near retirement.

Ashlyn Rollins-Koons is an investment professional practicing in Northern California and a doctoral student in Kansas State University’s personal financial planning program. Ashlyn’s research interests are in behavioral finance, religion and finance, natural disaster financial planning, and family financial socialization. She can be reached at ashlynr12@ksu.edu.

This paper was developed as part of a project co-led by Carol Anderson (the president of MQ Research & Education and founder and vice president of Money Quotient, Inc.) and Deanna Sharpe (associate professor in the personal financial planning program at the University of Missouri), with invaluable support from Thom Allison, CFP® (founder of Allison Spielman Advisors and MQ University faculty member). The Financial Planning Association provided funding for the research.

Note: Click on image below for PDF versions.

At the core of the practice of financial planning is establishing and maintaining a professional relationship with clients. The CFP Board has even codified the client relationship into the practice standards as the first step of the financial planning process (CFP Board 2019). But how can financial planners establish and maintain relationships? Moreover, how does a financial planner successfully build trust and maintain a committed relationship with their clients?

Early work by Sharpe et al. (2007) provides insight into these questions by asking financial planners and their clients what aspects of the planner–client relationship influenced trust and commitment in clients. Sharpe et al. (2007) explain that trust and commitment were not tied to just the financial details but rather the ability of the financial planner to communicate to their clients that they understood each of their unique life contexts, values, and situation. Sharpe et al. (2007) explain that their results indicate that through incorporating a financial life planning (FLP) perspective, the planner’s role shifts from “maximizing a client’s investment return to helping the client utilize financial resources to construct a meaningful life” (14). And that shift is what builds trust and ultimately establishes commitment.

FLP has been described as financial planning focusing on the quality of life, an individual’s historical and present relationship with money, and helping clients align their financial decisions to their values (Kinder Institute n.d.). More specifically, FLP can be defined as:

A comprehensive approach to planning that is appropriate and useful for all ages—young adults and those nearing retirement. It is based on the philosophy that the most successful and satisfying retirement experiences are based on a series of thoughtful, future-focused decisions made throughout one’s adult life. Skills, values, attitudes, resources, and relationships that are developed and honed during one stage of life all contribute to meeting the challenges and recognizing the opportunities of the next stage of life (Anthes and Lee 2001, 91).

The current study is a replication and extension of the early work of Sharpe et al. (2007) to explore the evolving role of financial life planning in building trust and commitment in the financial planner–client relationship. While early and important, the work of Sharpe et al. (2007) was limited in its integration of theoretical constructs and use of solely descriptive statistical analysis. To expand on Sharpe et al. (2007), the study at hand provides an in-depth exploration of the theory of trust and commitment developed by Morgan and Hunt (1994) with a focus on the antecedents to the formation of commitment and trust from a client’s perception. Structural equation modeling (SEM) explores these critical pathways of influence to provide invaluable insights into what aspects of the planner–client relationship aid (or hinder) the development of trust and commitment.

Theoretical Literature Review

In the foreground of Sharpe et al. (2007) was the theory of commitment and trust (Morgan and Hunt 1994). The theory prescribes clear antecedents to trust and commitment in any client relationship, including the financial planner–client relationship. One of these antecedents to trust and commitment is communication. Sharpe et al. (2007) focused their work solely on communication as an antecedent, drawing a delineation between communication abilities and commitment implied in the communication. The current study looks at all antecedents described in Morgan and Hunt’s (1994) theory, rather than only communication as an antecedent to trust and commitment.

Trust and commitment theory (Morgan and Hunt 1994) allows for antecedents—the predictive factors—to lead to commitment, trust, or both commitment and trust. The two key antecedents of developing commitment are the cost to terminate the relationship and the perceived relationship benefits that will be received. The two key antecedents to building trust are communication abilities and opportunistic behavior of the professional. In addition, the final antecedent (shared values) helps build commitment and trust. The theory posits that the presence of trust leads to a commitment from the client. We begin this theoretical literature review by describing trust and its antecedents, followed by commitment and its antecedents.

Trust

Trust in a financial planning context can be defined as the client (trustor) expecting the financial planner (trustee) to be reliable, honest, and competent (Cull and Sloan 2016). Trust within a relationship consists of the confidence one party has in another’s integrity and reliability (Morgan and Hunt 1994). Ultimately, trust is required in the client’s act of relying on the planner’s advice to achieve an outcome (Hunt, Brimble, and Freudenberg 2012). Financial planning can be challenging for a client to adequately evaluate due to the education and training required to understand some of the complexities of a comprehensive plan (Christiansen and DeVaney 1998). Furthermore, the issues addressed in the financial planning process can be emotionally laden to clients (e.g., end-of-life or estate planning), requiring a high level of trust, similar to trust developed with the therapist, to endure the discomfort of specific financial planning topics (Pullen and Rizkalla 2003). A client being transparent with financial assets, debts, habits, and goals can make a client feel vulnerable, requiring a client’s trust in their planner to be candid (Dubofsky and Sussman 2009). Trust has been found in several studies to be a key component for quality interaction in a planner–client relationship, as demonstrated by the reliance required on one another, the vulnerability involved, and the positive expectations established (Hartnett 2010; Sharpe et al. 2007). Alyousif and Kalenkoski (2017) found that the more clients trust their financial planner, the more likely they are to seek financial advice.

Antecedents to Trust

Two key antecedents to building trust are communication ability and opportunistic behavior of the professional. Morgan and Hunt (1994) explain that the planner must have communication ability to build trust. Communication ability is at the forefront of the original Sharpe et al. (2007) study that the current paper is replicating and thus will have a central role here. In the original study, Sharpe et al. (2007) diverged slightly from the theory in that they looked at communication ability in building trust and commitment. Their work separated communication into three domains: topics, tasks, and skills. Communication topics are what professionals talk about, such as retirement planning, risk management, and legacy planning (Sharpe et al. 2007). Communication tasks are the objectives you achieve—defining the scope of the engagement and gathering data. Communication skills are methods by which professionals communicate—nonverbal, verbal, and spatial. Sharpe et al. (2007) found that all three communication domains were highly associated with trust and commitment.

Opportunistic behavior is negative, so trust is preceded by an absence of self-serving or deceitful behavior from the adviser (Morgan and Hunt 1994). Clients who believe or observe that their advisers are not looking out for their best interests will have diminished trust (Morgan and Hunt 1994). Instead, a financial adviser who keeps an eye out for strategic opportunities suitable for a particular client’s situation would increase trust, according to Morgan and Hunt’s (1994) theory. When discussing planner–client relationships, Dubofsky and Sussman (2010) say that clients and planners have certain expectations of each other. If those expectations are not fulfilled, the relationship and the individuals will suffer. For example, a client expects an adviser to make decisions in their interest; if the planner does so, the planner will meet the client’s expectations. The parties would continue to build trust, or in Dubofsky and Sussman’s (2010) words, bond.

Commitment

Client commitment is essential for the planner’s business revenue model. Client commitment has been measured by whether a client has considered or has taken action switching advisers and one’s short-term intentions of continuing with their current adviser (Cheng, Browning, and Gibson 2017). A client who does not feel committed to the planner–client relationship will have a higher propensity to leave (Yeske 2010). Because the cost of onboarding new clients is higher than maintaining clients, a financial adviser is motivated to foster a client’s commitment to the planner–client relationship. Furthermore, the stakes are high concerning client commitment. Fulk, Watkins, Grable, and Kruger (2018) describe the profile of the individual who lacked commitment to their financial planner. They are (a) older, (b) have a higher level of household income, and (c) have a higher level of household net worth (Fulk, Watkins, Grable, and Kruger 2018). Because these characteristics typically represent a profitable client profile, it stresses the financial planner’s economic importance of client commitment. Research by Cheng, Browning, and Gibson (2017) reveals exciting insight into the topic of client commitment. They find that it was positively related to satisfaction, trust, the frequency of meetings, investment-related education communication, and the use of personal notes and greeting cards, whereas relationship commitment is negatively related to small talk about hobbies.

Antecedents to Commitment

The two key antecedents of developing commitment are the cost to terminate the relationship and the perceived relationship benefits (Morgan and Hunt 1994). One’s low level of commitment may be neutralized if the costs to terminate the relationship are high regarding the money, time, or energy needed to establish a new relationship. The complexity of a client’s circumstances, for example, is related to a client’s commitment to the planner–client relationship (Yeske 2010). The more complex their plan is, the more likely they will be committed, as finding a new adviser and starting the planning process over may create a significant time cost. If the perceived benefits of the relationship are high, then there will also be a greater commitment to the relationship. For example, Fulk, Watkins, Grable, and Kruger (2018) suggest a client might look at investment performance when considering whether to find a new adviser. Cummings and James (2014) caution advisers to avoid solely relying on quantitative benefits and suggest that psychological benefits (e.g., having a trustworthy source during significant life changes such as losing a spouse) may factor into clients’ commitment decisions.

Antecedents to Trust and Commitment

Shared values are the last antecedent incorporated in the Morgan and Hunt (1994) theory of trust and commitment. This antecedent is unique because it feeds into both trust and commitment. Shared values are directly related to the financial life planning movement (Levin 2003; Wagner 2000; Wagner 2002; Walker 2004). Financial life planning is a genre of financial planning that not only addresses the technical elements required (e.g., investment management) but goes beyond that by developing a holistic plan customized for the client’s unique goals, values, and beliefs (Sharpe et al. 2007). Financial life planning is also called “value-based planning” (Sharpe et al. 2007). The role of the financial adviser has evolved to offer a holistic approach that requires communication abilities to uncover the underlying values of the client (Sussman and Dubofsky 2009). The financial planner’s mission is to be able to aid the client in discovering their values and creating a shared vision of how those values are integrated into their financial plan; this is not unique to just financial life planning proponents. The CFP Board’s (2020) Practice Standards clearly state that understanding clients’ values are an essential aspect of the data collection phase of financial planning:

Not only should CFP® professionals obtain relevant quantitative information (e.g., age, family situation, income, expenses, cash flow, assets, liabilities, employee benefits, government benefits, retirement accounts/benefits, insurance coverage, estate plans, capacity for risk, etc.) and relevant qualitative information (e.g., the client’s health and life expectancy, family circumstances, values, attitudes, expectations, earnings potential, tolerance for risk, needs and goals, priorities, etc.), but CFP® professionals are also expected to clearly describe to the client what quantitative and qualitative information will be required and collaborate with the client to obtain that information.

In 2007, Sharpe et al. explored the planners’ and clients’ perspectives on planners’ ability to collect information about clients’ values (e.g., cultural and family values). They found the ability to foster shared values to be a contributing factor in developing trust and commitment, as the theory proposed. This paper will more precisely examine how the theory of trust and commitment (Morgan and Hunt 1994) plays out in financial planner–client relationships.

Methods

Data

This study used convenience sampling through multiple avenues to reach a sample of financial planning clients. The Financial Planning Association (FPA) provided a list of all members’ email addresses for the Money Quotient Research Consortium (MQRC) to email a request to participate in the study with a direct link to the Qualtrics survey for financial planners. FPA, Money Quotient, Michael Kitces, XY Planning Network, and the Financial Therapy Association posted an invitation to participate and a direct link to the survey on their social media outlets. The collection of planner data took place in the first quarter of 2021 and yielded 395 usable surveys. The data collected with the planner data is available for future studies.

After the electronic survey, planners were asked to help obtain clients’ perspectives by inviting five or more of their clients to participate in the client component of this research. To extend that invitation to their clients, planners were directed to provide a random number-generated hyperlink to their clients. To encourage client participation, the first 340 clients to complete the survey were given the option to receive a $50 Amazon gift card or a $50 charity gift card that could be donated to the charity of their choice. Client data collection took place in the first quarter of 2021 and resulted in 435 usable surveys. The data used in this paper only focused on the clients’ perceptions, but the dataset will be available to examine planner perceptions in future research. Demographic information for clients is presented in Table 1.

Data Analysis

Conventions for Variable Coding

The variables used in this study are Likert-type variables on a scale from 1 to 5, except for four questions, which are scaled from 1 to 7. The value 1 represents the strongest disagreement or the most negative view of the question, while 5 (or 7) represents the strongest agreement or the most positive view of the question. When the question wording was such that this convention was reversed, the variables were reverse-coded, which is noted in the variable’s description.

Dependent Variables

There are two dependent variables—trust and commitment. Trust was designed to measure the level of trust a client has in their financial planner and consists of five separate items (a = 0.77). Commitment was designed regarding the relationship between a client and planner and consists of six separate items (a = 0.73). The trust and commitment scales used for this study were created for the Sharpe et al. (2007) study. Both scales were assessed for internal consistency using Cronbach’s alpha. While a range of possible interpretations has been presented, generally, levels of 0.7 or higher are considered acceptable and, therefore, internally consistent across items (Taber 2018). As guided by the Morgan and Hunt (1994) theory of trust and commitment, the trust variable also serves as a predictor variable for commitment. In this way, one could describe trust as an intermediary outcome or a precursor to commitment.

Independent Variables

A total of five independent variables are considered antecedents of trust and commitment. Communication abilities and opportunistic behavior are hypothesized to be linked only to trust. Communication abilities are defined as the client’s perceived strength and effectiveness of communications with their financial planner and were measured using the scaled responses to six items (a = 0.72). Opportunistic behavior is defined as the client’s feelings toward their financial planner’s potentially opportunistic behaviors and integrity using the scaled responses to five items (a = 0.60). Opportunistic behavior’s internal consistency is below the generally accepted level for internal consistency. Still, the construct has robust CFA fit statistics (Kline 2016), which is a positive indicator of the measure’s consistency. Relationship termination costs and relationship benefits are associated only with commitment. Relationship termination costs are defined as the client’s perceived cost of ending the relationship with their financial planner and were assessed by scaled responses to the five items (a = 0.74). Relationship benefits are defined as the client’s perceived benefits of working with their financial planner and were measured by the scaled responses to six items (a = 0.76). A fifth variable, shared values, is associated with trust and relationship commitment. Shared values are defined as the client’s belief that their financial planner shares their underlying values and is assessed by the scaled responses to nine items (a = 0.78).

Analytic Methods

The survey data was coded, and initial analysis was completed using Stata Version 16 for Mac. Structural equation modeling (SEM) calculations, including confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), the measurement model, and the full structural model, were computed using MPlus Version 8.4 for Mac. The path model diagram, along with standardized coefficients and fit statistics, can be seen in Figure 1. The analytic method used in Mplus was maximum likelihood (ML). This analytical method treats all the variables, including latent variables, as continuous (Muthén and Muthén 2017). Under ML, missing data is handled using listwise deletion for any cases with missing observations. Maximum likelihood estimation resulted in a 1.16 percent reduction in the number of observations included in the SEM analysis, which would be expected to have a negligible impact on the strength of the analysis.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Summary statistics for the questions are presented in Table 2. The mean result for most questions indicated a slight skew to neutral and positive responses for clients. However, the statement “I do not question my planner’s recommendations” received a mean rating of 2.68 (SD = 0.85), while questions regarding staying with a financial planner indefinitely (M = 2.90, SD = 1.19) and being able to be persuaded to work with a different financial planner (M = 2.87, SD = 1.08) were less favorable. Notably, the last two questions are on commitment to the current financial planner. Planners received stronger scores in the domain of satisfaction and relationship termination. Satisfaction received a mean score of 3.74 (SD = 0.97), while follow-through received a mean score of 4.89 (on a 7-point scale, SD = 1.28). In communications, planners received a mean score of 4.90 (SD = 1.37) for asking questions to assure recommendations were understood.

Confirmatory Factor Analyses

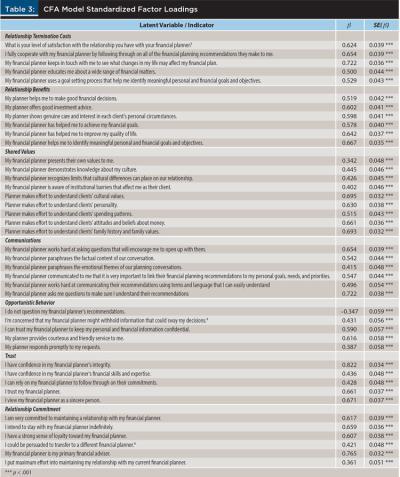

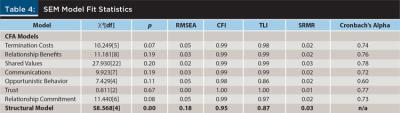

Confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) were performed on latent variables that represented the seven constructs in the model: (a) relationship termination costs, (b) relationship benefits, (c) shared values, (d) communications, (e) opportunistic behavior, (f) trust, and (g) relationship commitment. Loadings for each indicator on its latent variable are listed in Table 3. Complete CFA model fit data and Cronbach’s alpha for each latent variable are summarized in Table 4.

CFAs were performed using questions chosen a priori based on the Morgan and Hunt (1994) theory of trust and commitment. Each CFA was then optimized to eliminate questions that did not load well onto a construct, indicating that the question does not correctly fit into that domain. When indicated, covariances between related questions were added in the CFA models to help analyze model fit. While the latent variables were ultimately not used (in favor of summed scores), the CFA analyses, along with Cronbach’s alpha scores, helped verify each construct’s internal validity and consistency.

Relationship Termination Costs

During the CFA process, two questions were eliminated from this construct. Factor loadings for the remaining questions ranged from 0.50 for financial planners providing education to 0.72 for financial planners keeping in touch for changes. All loadings were significant with p < .001. The CFA model fit was good (c2[5] = 10.249; p = .069; RMSEA = .05; SRMR = .02; CFI = 0.99; TLI = 0.98). All fit statistics are within the ranges suggested by Kline (2016).

Relationship Benefits

The variances of one set of two questions were allowed to covary with each other, indicating interrelatedness between a client’s perception of good investment advice and their view of the planner’s care for their circumstances. Factor loadings ranged from 0.52 for planners helping the client make good financial decisions to 0.67 for planners helping make meaningful personal and financial goals. All loadings were significant with p < .001. CFA model fit was good (c2[8] = 11.181; p = .192; RMSEA = .03; SRMR = .02; CFI = .99; TLI = .99). All fit statistics are within the ranges suggested by Kline (2016).

Shared Values

The variances of five pairs of variables were allowed to covary with each other, which indicates a strong interrelationship between the questions that focus on the planner’s understanding of the client’s culture and values. This variance indicates the nuance in what each question is trying to measure, as the survey questions approach shared values from multiple angles. Factor loadings ranged from 0.34 (on the lower end of acceptability) for the planner presenting their values to the client to 0.70 for the planner making an effort to understand the client’s cultural values. All loadings were significant with p < .001. The variation in these two factors did not covary in the model, which may indicate that clients focus more on their values and whether the financial planner understands those values than on the financial planner’s values. CFA model fit was good (c2[22] = 27.390; p = .197; RMSEA = .02; SRMR = .03; CFI = .99; TLI = .99). All fit statistics are within the ranges suggested by Kline (2016).

Communication Abilities

One question was eliminated in the CFA modeling process, and the variances of two pairs of variables were allowed to covary with each other, linking the need to tie financial planning to goals and the financial planner communicating understandably and checking to assure that understanding. Factor loadings ranged from 0.42 for the financial planner paraphrasing the emotional themes of the client to 0.72 for the financial planner asking questions to ensure the client understands. All loadings were significant with p < .001. CFA model fit was good (c2[7] = 9.923; p = .193; RMSEA = .03; SRMR = .02; CFI = .99; TLI = .99). All fit statistics are within the ranges suggested by Kline (2016).

Opportunistic Behavior

One question was eliminated in the CFA modeling process, and the variances of two variables were allowed to covary, providing courteous and friendly service and the client not questioning recommendations. While it is not advisable to overstate this covariance, the potential connection between the client’s willingness to accept advice, how the advice is presented, and how the client feels they are treated is an interesting relationship. Factor loadings ranged from 0.35 (at the lower range of acceptability) for not questioning the financial planner’s recommendations to 0.62 for courteous and friendly service. All loadings were significant with p < .001. CFA model fit was good (c2[4] = 7.429; p = .115; RMSEA = .05; SRMR = .02; CFI = .98; TLI = .96). All fit statistics are within the ranges suggested by Kline (2016) and are quite strong in this regard, which is important since this construct had a lower Cronbach’s alpha value.

Trust

The variances of three variables were allowed to covary with each other, indicating a closer relationship between the client’s perception of the financial planner’s expertise and their follow-through, the client’s trust in them, and their perceived sincerity. Factor loadings ranged from 0.43 for the financial planner’s follow-through to 0.82 for the perceived integrity of the financial planner. All loadings were significant with p < .001. CFA model fit was good (c2[2] = .811; p = .667; RMSEA = .00; SRMR = .01; CFI = 1.00; TLI = 1.00). All fit statistics are within the ranges suggested by Kline (2016). The CFA model fit was especially strong, which is important for a dependent variable.

Relationship Commitment

The variances of three variables were allowed to covary with each other, indicating an associating commitment to the planner, the possibility of changing financial planners, and the planner’s role as the primary adviser. Factor loadings ranged from 0.36 for the client putting maximum effort into their relationship with their planner to 0.77 for having the financial planner as the primary adviser. All loadings were significant with p < .001. CFA model fit was good (c2[6] = 11.440; p = .076; RMSEA = .02; SRMR = .05; CFI = 0.99; TLI = .097). All fit statistics are within the ranges suggested by Kline (2016). The CFA model fit was very strong, which, as noted before, is important for a dependent variable.

Measurement Model and Change to a Summed SEM Model

In a latent variable SEM analysis, the next step after CFA is to construct a measurement model that combines the CFA models but does not yet add paths (relationships) between the constructs. As noted, the model is complex, with many constructs, variables for each construct, and a relatively small sample size. Hence, we could not get a measurement model to converge, which means that (1) a structural latent variable model would be extremely unlikely to converge, and (2) the validity of a structural latent variable model would be questionable even if it did converge. Based on this, and given the strong internal consistency measures from the CFA models and Cronbach’s alpha scores, we decided to use a summed structural model. Rather than using latent variables, a summed structural model will use a sum of the client responses for each construct. While this approach may lose the ability to analyze some of the variation and nuance between indicators for different factors, it should produce a valid path model between the constructs, along with appropriate measures of variation and significance.

Structural Model

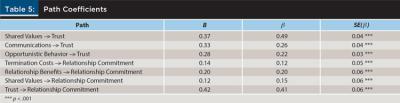

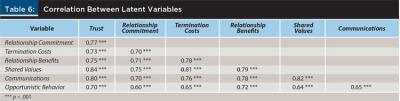

The structural model was deemed acceptable as it did not display strong model fit characteristics for all measures of fit. Chi-square was significant (c2[4] = 58.568; p < .001), but it is usually so when sample sizes are above 400; this is not a rare phenomenon and can be discounted (Kenny 2015). However, another measure was outside the range recommended by Kline (2016); RMSEA was 0.18, well above the acceptable range of 0.08 or less. TLI was marginally acceptable at 0.87. Two measures, CFI (0.95) and SRMR (0.03), were strong. Based on the preponderance of the measures, we are comfortable proceeding with the path analysis and considering the relationships it will indicate. Full model fit statistics for the structural model are presented in Table 4. Path coefficients for the structural model are presented in Table 5. Correlations between the model’s observed variables are presented in Table 6.

The model has seven structural (explanatory) paths, and all are statistically significant. Three paths lead to the trust dependent variable, and four paths—including one from trust—lead to the relationship commitment dependent variable. The R2 value for both dependent variables is significant as well. For trust, R2 is 0.77, and for relationship commitment, R2 is 0.65. The model explains 77 percent of the variation in relationship commitment between the client and financial planner and 65 percent of the trust between the client and financial planner.

The paths leading to trust are all significant at p < .001. The standardized coefficients for the paths leading to trust are 0.49 for shared values, 0.26 for communication, and 0.22 for opportunistic behavior. Two paths leading to relationship commitment are also significant at p < .001. The path from relationship benefits to relationship commitment has a standardized coefficient of 0.20, and the path from trust has the strongest direct loading on relationship commitment with a standardized coefficient of 0.41. Two paths leading to relationship commitment are significant at p < .05. The standardized coefficients for paths leading to relationship commitment are 0.12 for termination cost and 0.15 for shared values. Note that shared values load more strongly onto trust than relationship commitment. Also, there is an indirect path from shared values to relationship commitment; if that is considered, the total loading from shared values to relationship commitment is 0.55.

Discussion and Implications for Practice

Using structural equation modeling, this study found strong support for Morgan and Hunt’s (1994) theory of commitment and trust, and it reaffirmed the call by Sharpe et al. (2007) for the development of financial planning skills centered on building and maintaining relationships. The pathways prescribed by the theory were all statistically significant, and the R2 for trust and commitment were 0.77 and 0.65, respectively. These are strong R2 for social science, as some have claimed an R2 of .09 is sufficient to conclude in this field (Itaoka 2012). This means this study created a theoretically derived model that explains 77 percent of the variation in relationship commitment between the client and their financial planner and 65 percent of the trust between the client and their financial planner. The strong R2 suggests the antecedents to trust and commitment used in the model are highly relevant, which may indicate that technical skills (e.g., generating investment returns, tax saving strategies) alone may not be sufficient to build trust and commitment.

To summarize the theory and the results, the findings show that the two key antecedents to building trust are communication abilities and opportunistic behavior of the professional; that the two key antecedents of commitment are the cost to terminate the relationship and the perceived relationship benefits that the client believes they will receive; and that shared values build both commitment and trust. Finally, the presence of trust leads to client commitment. In this discussion, there will be an examination of each of these antecedents tied to tangible implications for the practitioner. These factors (or antecedents) will be discussed further in light of tangible takeaways for practitioners to implement in practice.

How to Build Trust

Trust is built through communication skills and the absence of opportunistic behaviors (Morgan and Hunt 1994). Communication skills in our study were focused on the planners’ ability to ask the right questions, paraphrase, and link recommendations to underlying goals, needs, and priorities. It was fascinating to see the differences in these communication abilities compared to the original Sharpe et al. (2007) study. Clients rated the planners’ ability much lower in the present-day study than in the past study. While reviewing this finding, the authors did not believe that present-day planners were worse communicators but rather that the present-day clients have higher expectations of their planners’ ability to communicate. Potentially with the rise of fintech and robo-advising, these communication skills have become more important to clients as it separates the financial planner from these more “affordable” alternatives.

Another key takeaway from communication was the importance of paraphrasing conversations with clients. It is essential to paraphrase the conversation’s factual and emotional content to ensure the client feels heard, understood, and validated (McCoy and Van Zutphen 2022). It is also vital to paraphrase so the planner can ensure they fully understand their clients’ underlying goals, needs, and priorities and give personalized and pertinent financial planning recommendations. Paraphrasing is also crucial during virtual engagements as it is easier to get distracted while meeting online rather than in person (Archuleta et al. 2021).

The second antecedent of opportunistic behaviors was also important to building trust. The results from this section of the analysis suggest there may not only be a potential connection between the client’s willingness to accept advice and how the advice is presented but also how the client feels they have been treated impacts their willingness to receive advice. Clients appear to have a strong need to believe in the integrity of the planner. Integrity goes beyond the fiduciary relationship required in our profession to encompass other aspects such as the quality and promptness of our treatment of clients. While Cheng, Browning, and Gibson (2017) found that frequent communication is essential to building trust, more research is needed to unpack the tangible skills required to ensure clients feel that they are receiving timely and accurate responses. This finding should encourage planners to consider their response time to their clients. Are there ways to work with a larger team to ensure timely responses? Is fintech or automation needed to ensure clients know when to expect a response?

How to Build Trust and Commitment (Shared Values)

One of the essential antecedents in Morgan and Hunt’s (1994) theoretical approach is the idea of shared values. The theory posits that shared values help create trust and commitment in clients. The results suggest that understanding your clients’ values, personality, spending patterns, attitudes, beliefs, and family history is foundational in building trust and commitment. However, what may be more interesting is that the data also seems to be trying to tell the story that clients find it very important that financial planners understand their own underlying beliefs, attitudes, and values around money. In the counseling world, we often refer to this process of self-exploration as the “self of the therapist” (Lum 2002). Research in the area of self of the therapist has found that this process of intentional self-exploration by a practitioner is linked with better technical skills, improved empathy with the client experience, stronger interpersonal skills, and lower rates of occupational stress (e.g., burnout) by the practitioner (for a review, please see Bennett-Levy 2019). Colloquially speaking, self-exploration is important as you may only be able to take your clients as far as you have gone. In addition, without self-exploration, you may present financial planning recommendations based on your own biases or underlying beliefs around money that are not aligned with your client’s values. While understanding and presenting one’s values as a planner is important, comprehending and aligning with a client’s values seems more imperative in establishing trust and commitment.

How to Build Commitment

Along with shared values, commitment is also built by relationship termination costs and perceived relationship benefits (Morgan and Hunt 1994). In essence, commitment is produced by positioning yourself as irreplaceable to your clients. Our assessment incorporated two questions about technical skills (i.e., “My planner helps me make sound financial decisions,” and “My planner offers good investment advice”). The rest of the questions were not built on technical skills but on the financial planners’ ability to meet their clients’ needs through action steps like checking in with clients, ability to educate clients on financial concepts, showing genuine care/interest in the client, and helping clients achieve the clients’ self-identified goals. These “soft skills” are the crux of building commitment in your clients. Technical skills can be replaced by other financial planners or technology, but financial life planning offers clients an irreplaceable human element. It allows the financial planner and client to share an ongoing financial journey as clients pursue goals that will lead to a meaningful life (as opposed to solving a financial equation). This idea becomes especially important given that, on average, clients were not so willing to stay with their financial adviser indefinitely. This could indicate that planners take client commitment for granted or that clients’ needs are not being met.

These soft skills take intentionality, especially given the increase in virtual financial planning engagement rates. Archuleta et al. (2021) explained that we often become more task-oriented when using virtual engagements to meet with clients. Financial planners would benefit from ensuring their agendas for virtual meetings include specific time set aside for connecting with their clients and discussing what’s going on in their lives. This is a time to continue engaging your clients in their values and goals. These are subject to change, especially in light of the tumultuous past few years (e.g., COVID-19, political unrest, inflation).

One interesting result from this section was how highly clients rated the importance of the question, “My financial planner keeps in touch with me to see what changes in my life may affect my financial plan.” This result suggests that planners must regularly check in with their clients (and if meeting with a couple, both partners). The advent of fintech can facilitate this check-in. Automating emails and social media to create a web of support so that clients feel like you are always just a click away can make them feel like you are providing the “white glove” service they may desire (Archuleta et al. 2021).

Finally, it is essential to note that included in this section was a question about client follow-through (i.e., “I fully cooperate with my financial planner by following through on all the financial planning recommendations they make to me”). Planners often refer to specific clients as resistant to follow-through or resistant to change (Klontz, Kahler, and Klontz 2016). Clients self-reported that they were good at cooperating with their planners. This counterintuitive finding is worthy of note as their sense of following through feeds into their commitment. Klontz, Kahler, and Klontz (2016) have a controversial line in their book when they say there is no such thing as resistant clients; instead, if a planner perceives resistance, it is a sign that the planner is erring. When clients do not follow through with their planning recommendations, it is not a sign of their stubbornness but rather a sign that planners need to slow down and investigate what is missing. Perhaps the recommendation needs more scaffolding to provide them with the skills to follow through (Sterbenz et al. 2021). For example, a planner may suggest a client sees an estate attorney but not provide referrals to conveniently located estate attorneys with sufficient availability. Perhaps the planner’s recommendation is not in line with their actual values and goals, and planners need to have more conversations to determine their client’s underlying desires.

An example of this could be suggesting the clients pick a charity for donations when they may want to help a family member reach their educational goals instead. Perhaps the recommendation asks them to change a behavior that serves a purpose in their life (De Shazer et al. 2021). An example of this could be if the clients are supporting an adult child financially, and you suggest reducing their financial contribution to the child. On paper, it may be the right decision, but perhaps supporting their adult child helps them feel close to their child and facilitate a relationship that otherwise would be strained. None of these examples mean that the financial planning recommendation is incorrect. Still, if a client is not following through, it is time for a financial planner to put the onus of figuring out why they are not following through on themselves rather than the client. Resistance is a symptom that you are missing something, not that the client is acting out against you, and if you push too hard when a client is exhibiting resistance, it may result in a fracture in trust (Ford and Ford 2010).

Trust and Commitment

This study focused on how clients build trust and commitment with their planners. Trust and commitment are essential in serving and retaining our clients, but it is also important to note that clients who trust their advisers are more than twice as likely to refer their advisers to friends and family (Madamba and Utkus 2017). Trust is a complex concept to define. Cull and Sloan (2016) completed a systematic review of how trust has been defined in financial planning articles and found that there have been at least 36 different definitions of trust. One such definition comes from Madamba and Utkus (2017); they explain that trust is multifaceted and has three essential components. The three components are defined as ethical (fiduciary responsibility to clients), functional (planners will deliver as promised), and emotional (creates peace of mind for the clients). These three components overlap with the antecedents described in our study and provide additional support that planners need to ensure that they are building trust with their clients, primarily since our results provided continued support for Morgan and Hunt’s (1994) theory that building trust will lead to increased commitment in clients.

As mentioned in the literature review, commitment is essential for revenue but also has been linked to increased financial planning efficacy (Yeske and Buie 2014). One fascinating aspect of commitment uncovered in the statistical analysis is that being in an exclusive relationship with a client is not as strong of an indicator of commitment as one would have thought. Planners working hard to build trust with clients would appear not to have to worry about referring their clients to other professionals. This finding may also provide additional support for a team approach to working with clients, as having timely responses and following through with promises were more powerful predictors of trust and commitment than being the primary adviser to a client.

This study provided important insights into how planners can facilitate trust and commitment from their clients using confirmatory factor analysis. Confirmatory factor analysis is a popular version of structural equation modeling that looks at the relationship between variables based on theoretically derived models (Bandalos and Finney 2018). A strength of this study is that the questions and measures were guided by theory before any analysis. This a priori selection of the theoretical questions is a strength of this study. It provides credence that the results are accurate and not a result of a statistical fishing expedition (Crede and Harms 2019). However, there are significant limitations that need to be expounded.

Limitations

Despite the robust findings of this study, some limitations must be noted. First, in terms of demographics, the sample was not diverse in terms of race/ethnicity and thus may not be generalizable. The sample was younger than the sample in the original Sharpe et al. (2007) study. Perhaps, since clients were provided an incentive to participate in the study, planners may have asked clients to participate in the study who were earlier in their accumulation stage of life because they would benefit more from the incentive than older, more financially established clients. Or, it could be that younger participants are more likely to participate in online surveys than older participants, according to some studies (Kelfve, Kivi, Johansson, and Lindwall 2020). Another limitation of our sample is that planners self-selected for the study and sent the survey to clients of their choice. It was not based on random sampling because we wanted to be able to link planners and clients in the larger dataset. Future studies should find ways to decrease sampling bias.

There were a few limitations due to the size of the sample, the complexity of the structural model, and the nuanced interrelationship between indicators used to measure different factors. We could not combine the CFA models into a measurement model (or full structural model) that converged. The statistics from a model that does not converge are unreliable, so we used the CFA models to confirm the strength of each of our constructs and then converted the factors from a latent variable to an observed summed score for each of our constructs. A measurement model is not needed when all variables are observed, so we were able to proceed to a structural model using the summed scores (Kline 2016).

Finally, Morgan and Hunt’s (1994) theory of commitment and trust is a marketing theory that perhaps focuses more on the planners’ outcomes rather than the clients’ outcomes. In other words, the theory was created to increase the number of clients a marketer may have at any point in time rather than examine the bidirectional positive outcomes of trust and commitment for both the practitioner and the client. Potentially there could be a stronger theory developed by financial planners to examine the planner–client relationship. As Buie and Yeske (2011) said, “CFP® practitioners have an urgent need to develop basic financial planning theory. Without underlying buttressing theory, how can we practice as a profession?” (38). The use of this theory also creates a need for a discussion regarding the ethical considerations of these suggestions on fostering trust and commitment. While the authentic intention of this study is to enhance the client and planner relationship by better understanding trust and commitment from both the client and planner perspective, the potential naivety of the approach is acknowledged. Determining the antecedents of trust and commitment generates the possibility of potential malicious misuse of the information. For example, after reading this study, advisers would now know that shared values are an antecedent to trust and commitment and could potentially falsely portray shared values with clients to close business. For this reason, a reminder is needed of the CFP® code of ethics’ call to act with honesty, integrity, and in a manner that reflects positively on the financial planning profession and CFP® certification (CFP Board 2022a).

Conclusion

The key takeaway from this paper is that a financial planner cannot rely alone on technical expertise to deliver upon the planner–client engagement. Instead, the findings emphasize how essential communication skills, understanding the client’s values and beliefs (e.g., shared beliefs), demonstrating integrity (e.g., the absence of opportunistic behaviors), and helping clients understand the tangible and intangible benefits of financial planning (e.g., cost to terminate and perceived benefits) are the skills that a financial planner needs to focus on to create trust and commitment with their clients.

The CFP Board (2022b) recognized this need by adding the psychology of financial planning as the newest principal knowledge topic in the evolution of establishing and developing client relationships and learning about client goals and values. As new financial planners graduate from various degree programs, they will come armed with basic knowledge and experience. But there is a need for current practitioners to engage themselves in developing and maintaining their proficiency in establishing trust and commitment within planner–client relationships. There are several continuing education and graduate school opportunities for novice and veteran planners to learn more communication skills. The Financial Therapy Association has a designation called the certified financial therapist (CFT) designation. Their program is a self-study program with online videos, resources, exams, and experience hours. There are also several online university programs. Kansas State University’s graduate certificate in financial therapy was the first program developed. Kansas State University’s certificate consists of four online, eight-week graduate-level courses that were designed as either a standalone certificate, or they can be taken as part of their master’s in financial planning degree. Creighton University has a graduate certificate in financial psychology and behavioral finance with five online, eight-week graduate-level courses. Golden Gate University and Texas Tech have online financial life planning programs, with Texas Tech having hybrid options for attendance (i.e., courses can be taken online, in-person, or both). Finally, the CFP Board added client psychology to their educational domain. The CFP Board released a book titled The Psychology of Financial Planning (CFP Board 2022b). It will have an increase in educational opportunities related to that domain for CEU credit, as well.

Citation

McCoy, Megan, Ives Machiz, Josh Harris, Christina Lynn, Derek Lawson, and Ashlyn Rollins-Koons. 2022. “The Science of Building Trust and Commitment in Financial Planning: Using Structural Equation Modeling to Examine Antecedents to Trust and Commitment.” Journal of Financial Planning 35 (12): 68–89.

References

Alyousif, Maher, and Charlene Kalenkoski. 2017. “(Mis)Trusting Financial Advisers.” SSRN Electronic Journal: 1–69. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.2955828.

Anthes, William, and Shelley Lee. 2001. “Experts Examine Emerging Concept of ‘Life Planning’.” Journal of Financial Planning 14 (6): 90.

Archuleta, Kristy L., Sarah D. Asebedo, D. B. Durband, S. Fife, M. R. Ford, B. T. Gray, M. R. Lurtz, M. McCoy, J. C. Pickens, and G. Sheridan. 2021. “Facilitating Virtual Client Meetings for Money Conversations: A Multidisciplinary Perspective on Skills and Strategies for Financial Planners.” Journal of Financial Planning 34 (4): 82–101.

Bandalos, Deborah L., and Sara J. Finney. 2018. “Factor Analysis: Exploratory and Confirmatory.” In The Reviewer’s Guide to Quantitative Methods in the Social Sciences. Routledge: 98–122

Bennett-Levy, James. 2019. “Why Therapists Should Walk the Talk: The Theoretical and Empirical Case for Personal Practice in Therapist Training and Professional Development.” Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry 62: 133–145.

Buie, Elissa, and Dave Yeske. 2011. “Evidence-Based Financial Planning: to Learn...Like a CFP.” Journal of Financial Planning 24 (11): 38–43.

Crede, Marcus, and Peter Harms. 2019. “Questionable Research Practices When Using Confirmatory Factor Analysis.” Journal of Managerial Psychology.

CFP Board. 2019. “The 7 Step Financial Planning Process.” Last modified February 28, 2019. www.cfp.net/ethics/compliance-resources/2019/02/the-7-step-financial-process.

CFP Board. 2020. “Practice Standards Reference Guide: Reference Guide to the Practice Standards for the Financial Planning Process.” Last modified November 4, 2020. www.cfp.net/ethics/compliance-resources/2020/11/practice-standards-reference-guide.

CFP Board. 2022a. “Code of Ethics and Standard of Conduct.” Last modified July 23, 2022. www.cfp.net/ethics/code-of-ethics-and-standards-of-conduct.

CFP Board. 2022b. “CFP Board Releases Six-Part Book on Psychology of Financial Planning”. Last modified April 27, 2022. www.cfp.net/news/2022/04/cfp-board-releases-six-part-book-on-psychology-of-financial-planning.

Cheng, Yuanshan, Chris Browning, and Philip Gibson. 2017. “The Value of Communication in the Client-Planner Relationship.” Journal of Financial Planning 30 (8): 36–44.

Christiansen, Tim, and Sharon DeVaney. 1998. “Antecedents of Trust and Commitment in the Financial Planner–Client Relationship.” Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning 9 (2): 1–10.

Cull, Michelle, and Terry Sloan. 2016. “Characteristics of Trust in Personal Financial Planning.” Financial Planning Research Journal 2 (1): 12–35.

Cummings, Benjamin F., and Russell James III. 2014. “Factors Associated with Getting and Dropping Financial Advisors Among Older Adults: Evidence from Longitudinal Data.” Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning 25 (2): 129–147.

De Shazer, Steve, Yvonne Dolan, Harry Korman, Terry Trepper, Eric McCollum, and Insoo Kim Berg. 2021. More than Miracles: The State of the Art of Solution-Focused Brief Therapy. Routledge.

Dubofsky, David, and Lyle Sussman. 2009. “The Changing Role of the Financial Planner Part 1: From Financial Analytics to Coaching and Life Planning.” Journal of Financial Planning 11 (8): 38–4.

Dubofsky, David, and Lyle Sussman. 2010. “The Bonding Continuum in Financial Planner–Client Relationships.” Journal of Financial Planning 23 (10): 66–78.

Ford, Jeffrey D., and Laurie W. Ford. 2010. “Stop Blaming Resistance to Change and Start Using It.” Organizational Dynamics 39 (1): 24–36.

Fulk, Martha, Kimberly Watkins, John Grable, and Michelle Kruger. 2018. “Who Changes Their Financial Planner?” Journal of Financial Planning 31 (8): 48–56.

Hartnett, Neil. 2010. “Trust and the Financial Planning Relationship.” Journal of the Securities Institute of Australia (JASSA) 1: 41–46.

Hunt, Katherine, Mark Brimble, and Brett Freudenberg. 2012. “Determinants of Client-Professional Relationship Quality in the Financial Planning Setting.” Australasian Accounting Business and Finance Journal 5 (2): 69–99. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1867907.

Itaoka, Kenshi. 2012. “Regression and Interpretation Low R-Squares.” In Proceedings of the Presentation at Social Research Network 3rd Meeting, Noosa. Mizuho Information and Research Institute, Inc. https://ieaghg.org/docs/General_Docs/3rd_SRN/Kenshi_Itaoka_RegressionInterpretationSECURED.pdf.

Kelfve, Susanne, Marie Kivi, Boo Johansson, and Magnus Lindwall. 2020. “Going Web or Staying Paper? The Use of Web-Surveys Among Older People.” BMC Medical Research Methodology 20 (1): 1–12.

Kenny, David A. 2015. “Measuring Model Fit.” David A Kenny. Last modified September 12, 2022. https://davidakenny.net/cm/fit.htm.

Kinder Institute of Life Planning. n.d. “What is Life Planning?” Last modified December 8, 2021. www.kinderinstitute.com/about-2/.

Klontz, Brad, Rick Kahler, and Ted Klontz. 2016. Facilitating Financial Health: Tools for Financial Planners, Coaches, and Therapists. National Underwriter Company.

Kline, Rex B. 2016. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. Guilford Publications.

Levin, Ross. 2003. “When Everything You Have is Enough.” Journal of Financial Planning 16 (2): 34–35.

Lum, Wendy. 2002. “The Use of Self of the Therapist.” Contemporary Family Therapy 24 (1): 181–197.

Madamba, Anna, and Stephen P. Utkus. 2017. “Trust and Financial Advice.” Vanguard Research. https://static.vgcontent.info/crp/intl/auw/docs/resources/adviser/Vanguard_research_Trust_and_financial_advice.pdf?20190930%7C173924.

McCoy, Megan, and Neal Van Zutphen. 2022. “Developing a Productive Client–Planner Relationship That Addresses the Psychological Elements of Financial Planning.” In The Psychology of Financial Planning. National Underwriter.

Morgan, Robert, and Shelby Hunt. 1994. “The Commitment-Trust Theory of Relationship Marketing.” Journal of Marketing 58 (3): 20–38.

Muthén, Linda K., and Bengt Muthén. 2017. Mplus User’s Guide: Statistical Analysis with Latent Variables. Muthén & Muthén.

Pullen, Courtney, and Leanna Rizkalla. 2003. “Use of Self in Client Relationships.” Journal of Financial Planning 16 (2): 36–37.

Sharpe, Deanna, Carol Anderson, Andrea White, Susan Galvan, and Martin Siesta. 2007. “Specific Elements of Communication that Affect Trust and Commitment in the Financial Planning Process.” Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning 18 (1): 2–17.

Sterbenz, Elizabeth, Dylan Ross, Raylee Melton, Jed Smith, Megan McCoy, and Blain Pearson. 2021. “Using Scaffolding Learning Theory as a Framework to Enhance Financial Education with Financial Planning Clients.” Journal of Financial Planning 34 (12).

Sussman, Lyle, and David Dubofsky. 2009. “The Changing Role of the Financial Planner Part 2: Prescriptions for Coaching and Life Planning.” Journal of Financial Planning 22 (9): 50–56.

Taber, Keith S. 2018. “The Use of Cronbach’s Alpha When Developing and Reporting Research Instruments in Science Education.” Research in Science Education 48 (1): 1273–1296. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11165-016-9602-2.

Wagner, Richard. 2000. “The Soul of Money.” Journal of Financial Planning 13 (8): 50–54.

Wagner, Dick. 2002. “Integral Finance: A Framework for a 21st Century Profession.” Journal of Financial Planning 15 (7): 62–71.

Walker, Lewis. 2004. “The Meaning of Life (Planning).” Journal of Financial Planning 17 (5): 28–30. https://doi.org/10.1108/aa.2002.03322aaa.001.

Yeske, David. 2010. “Finding the Planning in Financial Planning.” Journal of Financial Planning 23 (9): 40–52.

Yeske, Dave, and Elissa Buie. 2014. “Policy-Based Financial Planning: Decision Rules for a Changing World.” In Investor Behavior: The Psychology of Financial Planning and Investing. Edited by H. Kent Baker and Victor Ricciardi. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: 189–208.