Journal of Financial Planning: April 2021

By Kristy L. Archuleta, Ph.D., LMFT, CFT-I™; Sarah D. Asebedo, Ph.D., CFP®; Dorothy B. Durband, Ph.D., AFC; Stephen Fife, Ph.D., LMFT; Megan R. Ford, LMFT; Blake T. Gray, CFP®; Meghaan R. Lurtz, Ph.D.; Megan McCoy, Ph.D., LMFT, CFT-I™; Jaclyn Cravens Pickens, Ph.D., LMFT; and Gerald “Jerry” Sheridan

Executive Summary:

- The COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated the relevance and prevalence of virtual client communication.

- This paper offers a multidisciplinary perspective on best practices and theory that create a productive virtual environment to protect and enhance client outcomes.

- This paper integrates the theory of polymedia and the Therapeutic Pyramid to address the multiple types of media used in financial planning client relationships.

- Best practices in these key areas are introduced: necessary preconditions, professional’s way of being, and professional-client relationship dynamics—as well as skills and techniques associated with the psychological environment, physical environment, communication, and meeting effectiveness.

- Client confidentiality issues and cautions for advising at a distance are also presented.

Kristy L. Archuleta, Ph.D., LMFT, CFT-I™ is a professor in the Financial Planning program at the University of Georgia. She is a co-founder of the Financial Therapy Association, the Journal of Financial Therapy, and Women Managing the Farm. She has published numerous scholarly articles and co-edited two books on financial therapy. She serves on the board of directors for the National Association of Personal Financial Advisors and three editorial review boards. She is often featured in podcasts and major news media outlets and won awards for her cutting-edge research.

Sarah D. Asebedo, Ph.D., CFP®, is an assistant professor and director of the Life-Centered Financial Planning graduate certificate at Texas Tech University. Her practice and academic experience have earned notable industry and research recognition including the 2016 Montgomery-Warschauer Award, 2017 Top 40 Under 40 Award from Investment News, and the 2014, 2017, and 2018 Best Research Awards from the Journal of Financial Planning and Academy for Financial Services. She is a past president of the Financial Therapy Association and editor of the Journal of Financial Therapy.

Dorothy B. Durband, Ph.D., AFC, is a professor of personal financial planning and associate dean for academics and faculty in the College of Human Sciences at Texas Tech University. She teaches communication and counseling skills courses and her research interests are personal financial behavior and workplace finance education. She is the lead editor of Financial Counseling and Student Financial Literacy: Campus-Based Program Development.

Stephen Fife, Ph.D., LMFT, is an associate professor and program director of the Couple, Marriage, and Family Therapy Program at Texas Tech University. His research centers on couple therapy, the treatment and healing of infidelity, therapeutic change, and professional athletes and relationships. He co-authored two books on couple therapy: Couples in Treatment and Techniques for the Couple Therapist. He is the co-developer of an award-winning, innovative meta-model of psychotherapy called the Therapeutic Pyramid.

Megan R. Ford, M.S., LMFT, is the ASPIRE Clinic Coordinator in the College of Family and Consumer Sciences at the University of Georgia. She is currently completing a Ph.D. in financial planning, housing and consumer economics at UGA. She is a past president of the Financial Therapy Association and former copy editor of the Journal of Financial Therapy. She also co-authored The Fundamentals of Writing a Financial Plan. Her research interests center on couple financial dynamics, financial intimacy, and interdisciplinary collaboration and intervention.

Blake T. Gray, CFP®️, is a Ph.D. student and research assistant at Texas Tech University. He has eight years of experience in the financial planning profession in a teleservice capacity serving Vanguard clients. His research centers around how households perceive and manage their financial decision-making roles. His work has been published in Applied Economics Letters, Financial Planning Review, and the Journal of Positive Psychology.

Meghaan R. Lurtz, Ph.D., is a senior research associate at Kitces.com. In addition to her work on the site, she teaches in the personal financial planning master’s programs at Kansas State University and Columbia University. She is a past president of the Financial Therapy Association and has authored book chapters in Client Psychology. Her research has been published in Financial Planning Review, Journal of Consumer Affairs, and Journal of Financial Planning.

Megan McCoy, Ph.D., LMFT, CFT-I™, is a professor of practice and the director of the personal financial planning master’s program at Kansas State University. Her research on financial therapy and financial well-being has been published in a range of journals including the Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning, Journal of Family Economic Issues, and Family Relations among others. She serves as secretary for the Financial Therapy Association. She is also the associate editor of profiles and book reviews for the Journal of Financial Therapy.

Jaclyn Cravens Pickens, Ph.D., LMFT, is an associate professor in the Couple, Marriage, and Family Therapy program at Texas Tech University. Her research focuses on the influence of technology on romantic relationships and the practice of relational teletherapy. In addition, she provides training on teletherapy practices at the local, state, and national level to mental health professionals.

Gerald “Jerry” Sheridan is a Texas Tech Life-Centered Financial Planning Certificate graduate and a registered investment adviser representative with Emerald Blue Advisors, Inc. He focuses on retirement preparation, planning, and lifestyle continuation. He guides clients to maximize their retirement income and minimize their exposure to taxes. He is also a licensed life insurance agent.

Note: Though listed in alphabetical order, the authors have indicated this research was an equal authorship contribution.

JOIN THE DISCUSSION: Discuss this article with fellow FPA Members through FPA's Knowledge Circles.

FEEDBACK: If you have any questions or comments on this article, please contact the editor HERE.

NOTE: Click on the Figures below for PDF versions.

Financial planners are accustomed to communicating with clients virtually and in multiple formats (phone, video conference, email) given increased client mobility and preferences (Sheils, Tucker, Fox, and Dunkerley 2013). However, the COVID-19 pandemic has significantly accelerated the virtual meeting modality to the extent that it is now a necessity.

The unique environmental circumstances and increased stress caused by COVID-19 have impacted clients and financial planners (Bareket-Bojmel, Shahar, and Margalit 2020; Osterland 2020). Client communication and relationship development in a virtual setting presents unique challenges. For example, a virtual setting can affect how a family communicates and can potentially exacerbate or alter power imbalances amongst family members (Arellano 2020; Grady et al. 2011). Money conversations in any format are challenging as they have the potential for an array of emotions, psychological responses, and relational processes such as stress, anxiety, and conflict (Engelberg and Sjoberg 2006). With these considerations in mind, the need for effective client communication in a virtual format should be at the forefront of financial planning research and practice.

Research has made significant progress in understanding the interaction between money and the psychosocial environment. However, little is known about how a virtual setting might enhance or detract from money conversations within the context of financial planning.

Sensenig et al. (2020) found that no empirical studies had been conducted regarding financial planning in a virtual setting. As a result, Sensenig et al., looked to the mental health literature to draw connections to financial planning for two reasons: (1) high rates of counseling-like incidents exist in financial planning sessions (Dubofsky and Sussman 2009); and (2) the integration of client psychology in financial planning curriculum (Chaffin and Fox 2018).

Sensenig et al. (2020) found that virtual mental health services were just as effective, or more, as those delivered in person. They also found that there were additional benefits to virtual mental health, like decreased costs, increased practitioner reach (i.e., geographic distance), lower dropout rates, and increased ability to collaborate with other professionals. “These findings suggest financial planners might leverage a virtual delivery channel to provide effective recommendations while expanding their reach and providing an experience that is less stressful and more convenient” (Sensenig et al. 2020, pg. 48).

Kornegay and Kornegay (2019) made a similar suggestion: “While technology is sometimes seen as creating barriers to effective personal communication, it can also be harnessed to enable you to engage with your clients and prospective clients in ways that can be more personalized and effective than ever before and at a much lower cost in terms of time and dollars spent” (pg. 21).

It is not difficult to see how financial planners can quickly find themselves in uncharted territory when working with clients within the context of a challenging topic (money) while in a new format (virtual) for an extended period of time. Numerous articles are available that provide anecdotal suggestions for how to conduct virtual meetings and establish virtual presence (e.g., Frisch and Greene 2020; Henebry 2020). However, little is known about how these skills and strategies might affect the client relationship through trust, commitment, and client-centered outcomes like financial satisfaction and well-being. This is a significant research and practice gap that can no longer remain unaddressed given the opportunities and risks that virtual meetings offer. Grounded and evidence-based best practices are needed to illuminate the skills and strategies necessary to facilitate effective virtual client meetings for money conversations.

The purpose of this paper is to address this research and practice gap to lay the foundation for skills and strategies that shape virtual client meeting effectiveness, client outcomes, and direction for future research.

Because there is little existing evidence-based knowledge to understand these effects within the financial planning literature, this paper draws from existing theory and research from other professions to establish a starting point. Fortunately, robust research exists for virtual meetings within the mental health profession (Hertlein, Blumer, and Mihaloliakos 2014; Hilty et al. 2013; Pickens, Morris, and Johnson 2020), and an interdisciplinary approach is essential to draw on this evidence and advance the knowledge, skill, and effectiveness of a virtual approach in financial planning. Consequently, this paper includes a multidisciplinary author team to ensure the content represents expertise from researchers and practitioners in financial planning, couple and family therapy, financial therapy, and psychology.

Despite the lack of empirical research in virtual financial planning, theoretical articles provide insights to financial planners on potential challenges to virtual financial planning and ways to enhance the effectiveness of online communication. This paper proposes a theoretical framework that integrates the theory of polymedia (Madianou and Miller 2013) and the Therapeutic Pyramid (Fife, Whiting, Bradford, and Davis 2014), an empirically informed model of therapeutic effectiveness, thereby providing theoretically-informed best practices and considerations for working virtually with clients.

Theoretical Framework

The theory of polymedia (Madianou and Miller 2013) addresses the multiple types of media (e.g., phone, email, video conferencing) used in financial planning that facilitate virtual client relationships. The Therapeutic Pyramid (Fife et al. 2014) illustrates how to weave these technologies into relationship building strategies. This section provides an overview of these theories, as well as an integrated framework for successful financial planning in a virtual setting.

Theory of Polymedia. At its foundation, the theory of polymedia recognizes that the preconditions of access, availability, affordability, and literacy must be met to use technology in a way that adds value (Madianou and Miller 2013); these preconditions are examined throughout this paper. The theory of polymedia differs from other multimedia theories in that it also emphasizes “the social and emotional consequences of choosing between those different media,” as well as the moral responsibility that occurs when using varying types of media (Madianou and Miller 2013, pg. 170). The potential for emotional and social consequences (positive and negative) generated from various media options lies at the center of the modality choice—and movement amongst media options—for the financial planner-client relationship. The question becomes how the use of remote meeting technologies detracts from or enhances the strength of the financial planner-client relationship and, ultimately, the impact this has on client outcomes.

The theory of polymedia recognizes that many types of technologies are commonly integrated into our daily lives, like cell phones and email (Madianou and Miller 2013). For example, email and phone calls are often used in conjunction with a webcam in video conference meetings to facilitate the working alliance between the professional and client. Furthermore, the type of information included in the communications may differ based on the type of media that is used.

The theory of polymedia helps practitioners understand how these multiple media touchpoints work together and that these “communication technologies have implications for the ways interpersonal communication is enacted and experienced” (Madianou and Miller 2013, pg. 170). The communication technologies shape one’s perspective of how to enhance the socioemotional aspects of virtual client meetings. “Socioemotional aspects” refers to the emotional side of a relationship that focuses on building trust, rapport, and empathy (Klingaman et al. 2015). Thus, the focus is utilizing communication technologies to intentionally foster professional-client relationships, while also reaching clients’ financial goals. One of the goals of this paper is to use the theory of polymedia to increase the intentionality around the use of multiple media platforms and enhance the socioemotional experience for both the professional and client.

Therapeutic Pyramid

The relationship between the professional and client in the mental health field, often referred to as the therapeutic alliance (Greenson 2008), is the strongest therapist-influenced factor of effective therapy (Sprenkle and Blow 2004). Preliminary research by Sharpe et al. (2007) hints that there is a similar professional-client alliance that occurs within financial planning and that it, too, strongly influences the effectiveness of financial planning practices.

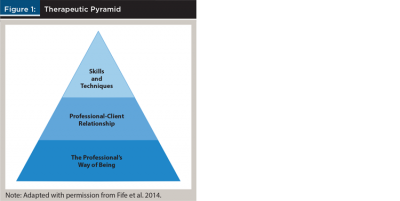

It’s difficult to separate therapeutic alliance from the techniques and skills that facilitate the alliance. Fife et al. (2014) proposed a meta-model set in a pyramid formation that conceptualizes the process and structure of three interrelated factors of working effectively with clients: (1) the professional’s way of being, (2) the therapeutic alliance, and (3) skills and techniques. The pyramid structure, shown in Figure 1, illustrates that the effectiveness of each factor rests upon the level below it. Researchers and practitioners can directly apply this model to understand successful financial planning.

At the top of the pyramid are the professional’s skills and techniques—essential knowledge and practices (Fife et al. 2014). The ability to effectively use these skills and techniques rests upon the quality and strength of the professional-client working relationship. Research indicates that the professional-client relationship accounts for about 30 percent of the variance of client outcomes (Asay and Lambert 1999). Fife et al. (2014) described the quality of the professional-client relationship as grounded in the professional’s way of being, which serves as a foundation to the professional-client relationship and application of skills (Figure 1).

Way of being is the professional’s “in-the-moment stance or attitude toward clients” (Fife et al. 2014, pg. 21). Way of being is a concept developed by Buber (1958) who emphasized the fundamental relatedness of human beings and proposed two different ways of relating to others: as objects (I-It) or as people (I-You). When objectifying others (I-It), we regard them as obstacles or means—things that are irritants or problems to us or things that can be used by us (Fife 2015). In contrast, when regarding others as people (I-You), we are open to them, alive to their humanity, and responsive to their needs (Fife 2015). Applied to financial planning, way of being means that professionals recognize the uniqueness of each individual, couple, or family with whom they work, rather than approaching clients in a one-size-fits-all manner.

Integrating the Theory of Polymedia and the Therapeutic Pyramid

When the Therapeutic Pyramid is laid within the theory of polymedia, moral responsibility is applied to the professional-client relationship, and managing social and emotional consequences of polymedia engagement are connected to both the professional-client relationship and the professional’s way of being (Fife et al. 2014; Madianou and Miller 2013).

The theory of polymedia’s moral responsibility includes using the appropriate type of media at the appropriate time. Tharp (2018) suggested there is a de facto fiduciary relationship created when the financial planner initiates a client interaction. This obligation requires that the financial planner take on the responsibility to create and enforce the entire environment in which the transactions take place. This environment will include aspects concerning technology platform decisions, the words being used, the appearance of the virtual meeting, and the clothes the planner is wearing. The planner must be proactive in making overt and thoughtful decisions prior to the session that encourage the client’s behavioral current reality and learned emotional reactions during the session.

Consider the situation when someone breaks up with their partner via text. Was using text messaging in this situation the morally responsible choice to make? Likewise, in a professional-client relationship, moral responsibility would encompass the prudence enacted when delivering interpersonal communication. For example, communicating sensitive information through email rather than using a secure mode of media, or leaving a voicemail when permission was not granted, could breach confidentiality and undermine the trust of the professional-client relationship. Similarly, emailing a client a comprehensive financial plan without discussing it may have negative emotional consequences, including increased anxiety and decreased motivation to work toward the clients’ goals.

Culture also influences moral responsibility. For example, when in-person meetings cannot occur, some clients may prefer to meet using video conferencing software, while others prefer to meet via phone.

At the foundational level, professionals must understand how their attitudes (way of being) toward polymedia affect the client and the outcomes of their work together: a client might detect a professional’s negative attitude toward videoconferencing, which could negatively affect the openness of the relationship. A professional might find it difficult to connect and manage clients’ emotions and dynamics virtually, or it may seem easier because the professional and client are not in the same room. In other words, it might be easier to ignore clients’ emotions or fail to pick up on their non-verbal cues in a virtual setting. Virtual communication could also make it easier for the professional to hide their own emotions, attitudes, and non-verbal cues because of a perceived media barrier. These scenarios illuminate how the professional’s way of being can affect client relationship outcomes.

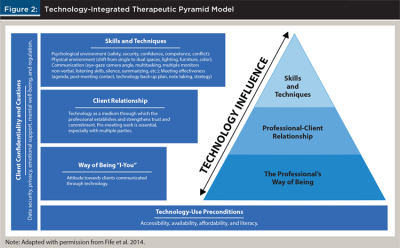

Figure 2 illustrates how technology influences the three interrelated factors of the Therapeutic Pyramid that facilitate effectively working with clients. At its foundation, technology-use preconditions represent the prerequisites of virtual services, including accessibility, availability, affordability, and literacy. Running vertically from top to bottom of the model is client confidentiality and cautions, which increase with virtual services.

The remainder of this paper will describe how the theory of polymedia (Madianou and Miller 2013), combined with Fife et al.’s (2014) Therapeutic Pyramid meta-model, provide new insights for best practices in virtual financial planning. It will begin with a description of preconditions required to start meeting virtually: accessibility, affordability, availability, and literacy. A discussion of the professional-client relationship, the professional’s way of being, and the interaction between these two elements will follow. The focus will then shift to virtual skills and techniques and, finally, risks professionals must consider when working with clients at a distance.

Theoretically Informed Virtual Meeting Best Practices

Preconditions: Accessibility, Availability, Affordability, and Literacy. Consistent with the theory of polymedia, preconditions to virtual services must be considered to ensure the appropriate technologies are accessible, available, affordable, and understandable to both the professional and client.

The professional should discuss with the client whether services can be delivered via asynchronous methods (e.g., email), synchronous without visual information (e.g., phone calls), or synchronous video conference services. Synchronous video conference services will necessitate a platform to provide the technology-assisted services, which requires that professionals identify whether HIPAA/HITECH regulations should be followed, whether a platform offers a Business Associates Agreement (BAA), and which type of functions are required to offer services (i.e., screen share, whiteboard, multisite conferencing, payment portals, video recording, live auto captioning, transcription).

A potential barrier to accessibility, availability, and affordability is the quality of internet bandwidth and technology utilized to deliver and access services. Professionals should inform clients about all required technology and level of bandwidth recommended to access technology-assisted services, as it can affect both the audio and visual transmission. Testing bandwidth quality prior to a session is helpful, as well as minimizing the number of devices utilizing the internet during the time of the session, closing out all non-necessary applications and browser windows before the session and, if possible, using an ethernet cord connected directly to a router.

Way of Being. Once preconditions are considered, the professional can incorporate each layer of Fife et al.’s (2014) pyramid into virtual client meetings. Consistent with Fife et al.’s model, the professional-client relationship, skills, and techniques employed are influenced by the professional’s way of being. Therefore, way of being should be the first consideration before any relationship-building or skills, techniques, or communication strategies are applied. Professionals must be mindful of their in-the-moment response or reaction to clients—as either objects or as people—in both virtual and in-person settings. Those who are too task-oriented, become frustrated or impatient with clients, overgeneralize or stereotype others, or focus primarily on their own financial gains risk shifting into an objectifying view of clients—seeing them either as a thing they have to deal with (i.e., an obligation, problem, irritation) or as a means to their own ends.

Professionals engaging with clients virtually may need to be particularly mindful of their way of being with clients. Clients often sense the way in which they are viewed, and an I-It way of being, will likely have a negative impact on the relationship, regardless of the financial planner’s knowledge and skills (Fife et al. 2014). On the other hand, clients respond very well when they are authentically seen and heard. Professionals who approach clients with an I-You way of being develop relationships of respect, trust, openness, and collaboration with clients. This is accomplished in virtual meetings as financial planners demonstrate genuine interest in their clients, listen carefully to their concerns and financial goals, and are responsive to their needs.

To understand their own way of being, financial planners must first reflect upon themselves, their own personal issues, attitudes, behaviors, and reactivity that may cloud their interactions with their client, and countertransference that may occur. They must also recognize their position of expertise and how their desire to be correct may undermine their clients’ reality (Whiting, Oka, and Fife 2012).

In a virtual space, way of being may not be communicated as intended or as efficiently or effectively due to the nature of polymedia. This makes the professional’s recognition of their own way of being even more important in facilitating the professional-client relationship. To assist financial planners in facilitating a client-focused way of being and fostering a strong virtual professional-client relationship, a review of communication best practices for virtual meetings is presented.

Professional-Client Relationship. The strength and effectiveness of the professional-client relationship rests directly upon the professional’s way of being with the client, which then shapes the application of skills and techniques. Thus, the professional-client relationship is the next area of consideration for virtual client meetings. While financial planning experts and researchers have emphasized the professional-client relationship, its empirical treatment has been modest compared to research in mental health, where scholars have devoted significant attention to its influence on client outcomes.

In financial planning, research shows that communication skills are associated with trust and commitment to the financial planner (Sharpe et al. 2007); however, little is known about how—and in what ways—the strength of the relationship affects client outcomes. Therefore, it is difficult to determine how a shift from in-person to virtual services might pose challenges to or enhance the client relationship and, consequently, client outcomes.

Fortunately, mental health research can provide insight into these potential effects. Research has shown that among all factors associated with successful therapy outcomes, the client relationship is the most important therapist-influenced factor (Asay and Lambert 1999; Horvath 2001; Wampold and Imel 2015). Research also has shown professionals can establish an effective working client relationship in virtual counseling sessions (Norwood et al. 2018; Simpson and Reid 2014). Similar to a therapeutic setting, the professional-client relationship is at the heart of successful financial planning services. Effective working relationships require that financial planners build trust, commitment, and rapport (Hunt, Brimble, and Freudenberg 2011). Virtual services may require additional effort to connect with clients and overcome potential challenges when using a variety of media.

When working with couples or family groups, financial planners must develop and manage relationships of trust and commitment with multiple parties. This expanded client relationship requires financial planners to simultaneously build a working relationship with each member of the client system (D’Aniello and Fife 2020).

Relationship-building strategies may be challenging in virtual settings where it is difficult to have an impromptu interaction with individual family members when conducting large and remote meetings. Instead, pre-family meeting work is needed to build these individual relationships. Furthermore, a strong professional-client relationship includes consensus on goals—something that can be complicated when working with a couple or family, as individual family members will likely vary in their values, motivations, and interests (Davis and Hsieh 2019).

Skills and Techniques. In the Therapeutic Pyramid, skills and techniques refer to the therapist’s application of models, techniques, and skills with clients. Wampold and Imel’s (2015) research found that only 8 percent of the variance of client change was due to the therapist’s model and techniques. However, this does not mean that skills and techniques are not important; rather, they work together with the client relationship to create successful client outcomes. In virtual work with clients, an additional layer of skill and technique is required that goes beyond the theory of polymedia’s preconditions of accessibility, availability, affordability, and literacy (Madianou and Miller 2013). These skills and techniques are organized into these areas: (a) the psychological environment, (b) the physical environment, (c) communication skills, and (d) meeting effectiveness.

Psychological Environment. Effective delivery of services requires that clients feel mentally and emotionally safe, so they can fully engage in the conversation (Timulak 2007). While professionals cannot control all aspects of the clients’ psychological environment, they should do everything possible to create an environment in which clients feel psychologically safe, emotionally present, confident, and secure in the relationship so they fully engage in the conversation. A working relationship that generates this secure psychological environment is facilitated by technology competence and the process of providing virtual services (Maheu et al. 2018). When financial planners are new to video-assisted professional services, it is important to prepare through role playing with colleagues to increase familiarity and reduce anxiety so virtual communication is not a barrier to client connection. Financial planners might also reduce clients’ anxiety through a short test call or free 15-minute consultation.

The financial planner’s preparation and confidence with the process of virtual interactions will increase clients’ confidence in the professional rather than raising questions about competence. The recommended information for supporting clients in preparation for change to both the physical and psychological environment may seem overwhelming. Financial planners can develop a Virtual Service 101 document that provides information on required technology for virtual services, optimal bandwidth, ways to test bandwidth, and creating a professional environment for virtual services. An additional recommended component of a Virtual Service 101 document is “troubleshooting technology” that covers common technology-related issues, how to fix them, and who to contact to resolve problems.

Another inevitable aspect of the psychological meeting environment is conflict that can vary from minor differences to extreme and pervasive arguments. Conflict can exist between the professional and client but is most often observed within the client unit. Conflict is just as relevant in a virtual setting as it is in a face-to-face one. In fact, the technology itself can cause imbalances in the conversation that can exacerbate conflict, such as access to a webcam or strong internet connection. People tend to respond to conflict in different but predictable ways (Asebedo and Purdon 2018), and it is critical to watch for these conflict response patterns in a virtual setting, although it might be harder to identify them and the financial planner will need to develop expertise in this area to pick up on subtle cues that may be further muted by technology. An understanding of clients’ personalities, conflict styles, and resolution strategies prepares financial planners to adjust the conversation to give voice to less assertive clients and to increase cooperation (Asebedo and Purdon 2018). Multiple forms of media may further complicate creating goal consensus and resolving conflict; nonetheless, creating shared understanding is important for a strong working relationship and is possible with patience and understanding, despite media challenges.

Physical Environment. While technology-assisted professional services have demonstrated equivalent effectiveness to in-person meetings (Hilty et al. 2013), the use of technology to deliver services changes the way in which these services are conducted (Bischoff et al. 2004; Springer et al. 2016) and requires special consideration and creativity to overcome barriers. One of the foundational considerations is the shift in control over the professional environment. With in-person services, the financial planner has control over their office and the ability to create an environment conducive to providing optimal services; however, the transition to a virtual setting creates a situation where two or more environments are used during service delivery. Thus, financial planners should consider all locations as professional spaces (Luxton, Nelson, and Maheu 2016) and give special attention to which type of environment is required to deliver technology-assisted services; moreover, financial planners can support clients in developing a space they feel comfortable in, that removes or limits distractions (both over technology and in the selected room), and that enhances auditory and visual quality. Lighting is a critical factor for quality visual information that aids in non-verbal communication. The location and type of lighting source will impact how well participants see one another. The room should be well lit, and backlighting should be avoided (Luxton et al. 2016); light sources (including natural light) are generally most effective when placed in front of a person and may reduce the quality of visual information if located in front of the camera or behind the person.

Another consideration is the design of the room itself. Previous research on the financial planning office environment and its impact on client stress found, for example, that the traditional office (i.e., a formal desk) when compared to a more therapeutic office (i.e. a couch, moveable chairs, no coffee table separating the furniture) was less conducive to information gathering and lowering client stress (Britt and Grable 2012; Grable 2017). Financial planners will want to consider designing home office spaces, even if the client can only see a small portion of it, with these previous findings in mind. For instance, perhaps consider having a couch or a calming painting in view behind the planner. Avoiding traditional office images and set-ups in a home-office may be just as valuable as avoiding them in a traditional office.

Communication Skills. Eye contact is an important component of non-verbal communication and is accomplished differently in virtual meetings. Because of the location of most cameras, individuals appear as though they are looking down rather than at the other person’s face and eyes (Bohannon et al. 2013). Both financial planners and clients should consider how the location of and proximity to the camera provides different types of information.

Researchers recommend placing cameras at the top center of the primary monitor so information is communicated at eye-gaze angle (Tam et al. 2007), which refers to making eye contact with the person on the monitor as opposed to the camera—thereby giving the perception of looking away (Luxton et al. 2016). Alternatively, positioning the image of the client near the camera—wherever it is located—will enhance the appearance of eye contact. It is also important to not appear distracted if you need to break eye contact. For example, when looking at a second monitor with client information or taking notes, the client only sees that you are looking away from them. If two screens are necessary, informing clients what is on the other screen will help reduce distractions and enhance client connection. To maintain eye contact, move any necessary active windows to the screen with the camera. Professionals should ensure that all participants in the session are visible to all in attendance. If multiple people are attending in the same location, the camera will need to be positioned so all people in the room are visible. Financial planners may consider sitting back from the camera so hands and arms can provide non-verbal cues (Bohannon et al. 2013).

Various video-conferencing platforms display information in unique ways; therefore, financial planners must be aware of how clients experience the platform in relation to what they see, the size of the video window, and whether all individuals on the call can see one another. To this end, professionals may want to try videoconferencing with their personal networks who are unfamiliar with the video-conference platform and ask them about their experience—even going so far as to assist a family member in changing what they see or how they see it so on an actual client call, the planner would have experience instructing the client.

These considerations also extend to what occurs during screen-sharing functions. Practicing screen sharing and manipulating the technology to share with clients prior to the real-time client meeting is helpful. For instance, the planner may display a spreadsheet or a table within the firm’s financial planning software, but the spreadsheet or table appears too small for the client to read. Being aware of these seemingly minor details prior to a client meeting can make a difference for staying connected with the client and enabling them to follow along.

Finally, many platforms include picture-in-picture functions in which the planner can see their own video as well as those of the other participants in the session. This information can provide insight to financial planners about how clients are receiving them (i.e., if hand gestures and facial information are in frame and easy to see); although some might find this distracting (Fosslien and Duffy, 2020; Luxton et al. 2016). Armed with this knowledge, financial planners can utilize the video to check in on clients but will also want to determine how to minimize their own visual image (while not hiding it from the client), if necessary, to enhance presence and client focus.

Earlier in this paper, it was suggested that financial planners consider conducting and recording a mock client session with a colleague and then watching that session. An additional benefit to this role play is to raise awareness of non-verbal behavior that might distract and detract from the interaction, such as fidgeting, looking down or away, excessive note taking, removing silence with filler words such as “um” or “so,” etc. The camera and microphone can intensify these behaviors and become more distracting with teleservices (Luxton et al. 2016). Financial planners—even those with experience—should be cognizant of these subconscious non-verbal behaviors that can vary when the setting shifts from the more familiar in-person meeting to virtual.

Videoconferencing fosters the financial planner’s ability to establish strong client connections through careful listening, being attuned to clients’ needs and concerns, and expressing understanding (Maheu et al. 2018). Taking less time to talk and more time to listen are also often recommended and vital to virtual meetings (Jaffe and Grubman 2011). Slowing down to focus on the client’s message instead of preparing a response is key to maintaining presence and processing client dialogue to establish understanding. Relevant listening tools include maintaining curiosity, asking “what if” questions, and using statements or questions (such as “Tell me more,” or “Is there anything else?”) to invite clients to share and elaborate (Grable and Goetz 2017).

Additionally, allowing for silence is an important skill for virtual meetings. Silence permits a client to reflect on what was said, while also allowing time to process their thoughts and formulate a response. Allowing additional time for a response to an open-ended question or prompting is also recommended. This extra pause also accommodates delays in audio or video, thereby preventing unintended interruptions and talking over the other person. Use of minimal encouragers are useful (small verbal and non-verbal signals to indicate listening and following what is said) and can include nodding, smiling, or a few words encouraging clients to continue talking.

Paraphrasing and summarizing provide a clarifying check of whether the financial planner accurately received or correctly perceived the information shared by the client, which is essential in virtual meetings where more communication obstacles are likely to exist. Furthermore, distractions may occur during a virtual meeting, especially when the client and/or the financial planner are working from home where other family members or pets are present. Given these potential distractions, it is helpful to periodically summarize what has been communicated. Another listening strategy is to ask the client to summarize key points from their perspective. With an increased level of potential distractions in a virtual setting, financial planners may wish to summarize more than is typical.

Lastly, listening for what clients may not be saying is a learned skill. This allows the financial planner to do a congruency check to determine and observe whether non-verbal behaviors are consistent with verbal statements. However, this may be more challenging to observe in a virtual setting when all non-verbal behaviors (e.g., body language, gestures) may not be visible to the financial planner.

Meeting Effectiveness. Guidelines that improve meeting effectiveness typically start with setting an agenda, communicating that agenda in advance, and keeping the meeting focused on information provided beforehand (Frisch and Greene 2020; Prossack 2020). The financial planner should make restrictions and boundaries known to the client as they agree to conduct a virtual meeting, such as limiting multitasking, distractions, and access by other parties during the meeting. Before the first meeting, the financial planner can facilitate a practice session for the client to see how the meeting will take place and to make sure the technology works well. The financial planner can send complex documents or those that are hard to see on screen in advance of the meeting. The financial planner should take the responsibility of providing a back-up plan to address a technological failure, which could include arranging a telephone contact if the visual tool fails. The financial planner should always follow up with the client after the virtual session to capture the client’s feelings, ideas, and conclusions.

The initial meeting conversation should focus on setting expectations for the virtual interaction to ensure mutual understanding by the client and financial planner. This could be achieved by inviting clients to share which elements would be important to them in a virtual meeting. Financial planners who plan to take notes should mention this at the beginning of the meeting (Grable and Goetz 2017). Keep in mind that shuffling papers or typing are often captured by the microphone and may detract from the meeting or imply distraction, so it is important to minimize this as much as possible.

Client Confidentiality. From a theoretical perspective, client confidentiality spans across the Therapeutic Pyramid to way of being, the professional-client relationship, and skills and techniques (Fife et al. 2014)—as well as the theory of polymedia domains of social and emotional management, moral responsibility, and literacy preconditions (Madianou and Miller 2013). Financial planners must take care to mitigate increased client confidentiality risk exposure when shifting from an in-person to virtual environment. Perhaps the primary new area of client confidentiality that is unique to the virtual setting is the dual environment (separate planner and client spaces) and the potential for financial planners to conduct meetings at home. Ensuring the professional and client’s physical locations are quiet, private, and secure can help establish a safe and trustworthy environment (Maheu et al. 2018). Both clients and professionals should consider times of the day that would lessen privacy concerns and limit disruptions (Luxton et al. 2016).

With respect to client meetings and discussing confidential information at home, financial planners should ensure the following:

- That they and their clients are in a room with closed doors (Lever and Oten 2020).

- Position the screens so the clients’ faces cannot be seen if someone is outside and looking through a window and disclosing who else is in the clients’ location that may overhear session information such that clients are clear about the level of privacy they can expect (Myers and Turvey 2013).

- Pan the camera around the room to show the client that it is a confidential space. Have the client do the same, especially if sensitive information will be shared during the meeting (Lever and Oten 2020).

- Inform clients if you have a Google Assistant, Amazon Echo, or Apple HomePod and discuss the potential breach of confidentiality that voice assistants pose—and then discuss alternatives, such as turning off the device or changing locations (Lever and Oten 2020).

- Inform clients in written documents—such as informed consent—and verbally discuss issues related to confidentiality and privacy with technology and accessing services from multiple locations in which the professional no longer has control.

It should be noted that prior to COVID-19, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) recommended that planners have cybersecurity policies created that outline strategies for preventing, detecting, and responding to cybersecurity threats (SEC 2015). The SEC (2015) also recommended that an annual review testing these policies and procedures should be conducted. Further, advisers should create a business continuity plan, so procedures outlined amid significant business disruptions are in place (SEC 2016). As part of a cybersecurity policy, financial planning firms should already have created both a hardware (e.g., phones, desktops, laptops) and software (e.g., CRM, custodian, financial planning) inventory spreadsheet that lists everything involving data (Cleary 2018). If the firm does not have either of these inventories in place, now is the time to create them (Lever and Oten 2020), including personal computers employees may be using while working from home.

Additional Cautions and Considerations for Advising at a Distance

Stress and Mental Health. Additional cautions and considerations associated with advising clients at a distance generally involve data security and privacy, client confidentiality, regulatory issues, and communication challenges inherent in using technology. Additionally, clients’ mental well-being, heightened emotions, and increased stress are unique concerns becoming more prominent and may challenge or complicate virtual work with clients.

Although information is still sparse, a handful of studies have demonstrated empirical relationships between important client domains, like physical health and financial distress, and prevalent mental health concerns, like anxiety and depression (Assari 2019; Bridges and Disney 2010; Sweet et al. 2013). Since the COVID-19 pandemic, these issues have become even more pronounced. The U.S. has seen a clear and dramatic rise in reported levels of anxiety, stress, depression, and economic uncertainty. A recent Kaiser Family Foundation poll showed that nearly half of Americans reported the recent health crisis was impacting their mental health negatively (Achenbach 2020). Further, one national emergency hotline for emotional support led by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration noted more than a 1,000 percent increase in calls when compared to numbers in April 2019 (Wan 2020). This has also led to a spike in individuals and families seeking help from mental health professionals. For instance, online therapy platforms like TalkSpace have seen massive increases in demand, noting an increase to their clientele by 65 percent since the pandemic hit (Wan 2020).

With the emotional toll, isolation, and economic stressors felt by many, clients may reach out to financial planners for support, guidance, and reassurance, particularly as market volatility and economic turmoil persists. Professionals may notice that clients are exhibiting a higher state of stress or crisis in virtual meetings, which can be especially difficult for financial planners to navigate in a virtual environment because a comforting physical presence and communication techniques and strategies may be hampered. With the absence of mental health training and counseling experience, most financial planners are not equipped to manage the majority of these concerns themselves. However, they may still serve as a trusted support person, able to provide a listening ear and helpful resources.

With this in mind, financial planning professionals should not only be aware of these challenges when conducting virtual financial planning services, but also consider these strategies as a way to mitigate risks: (1) increase attention to aspects of the client’s psychological environment and incorporate pre-meeting assessments or questions about recent feelings of stress, like the Perceived Stress Scale (Cohen 1994), as a way to better understand state of mind; (2) curate a list of recommended well-being resources to offer clients, such as websites, apps, or books; and (3) create referral relationships with mental health professionals who offer teletherapy services in the event that a client requests a referral for themself or a loved one. Identifying client resources can be accomplished through connecting with colleagues or professional membership associations (e.g., Financial Therapy Association, American Psychological Association, American Association for Marriage and Family Therapy)—several of which offer searchable networks of practitioners who may possess the expertise needed to manage stress or mental health concerns.

Regulation. Using new technology to communicate with clients brings several regulatory challenges. Adoption of new products introduces new risks and compliance costs. Some advisers may forgo new products due to the costs. Another challenge is that regulations are not uniform to all firms and with different levels of certification and licensing. There is no uniform standard to guide planners, other than the fiduciary and moral discussions covered previously. Tharp (2020) found that varying record-keeping requirements for different methods of communication resulted in firms altering how planners respond to clients. Clients may also be resistant to changing communication types based on regulatory requirements. For example, clients who are used to sharing personal information privately and in person, may object to a financial planner recording virtual meetings (Tharp 2020). Despite the challenges that compliance brings to adopting new technology, the benefits from virtual services can outweigh the costs. Technological solutions to compliance challenges exist, such as the ability to transcribe, record, and store virtual communications (Smarsh 2021). Professionals should carefully consider potential benefits as they consider compliance challenges to implementation.

Conclusion

This paper has outlined theoretical foundations and best practices for virtual services in financial planning. As illustrated in Figure 2, technology influences the three interrelated factors that facilitate effectively working with clients. The model—informed by both the Therapeutic Pyramid (Fife et al., 2014) and the theory of polymedia (Madianou and Miller, 2013)—was developed to support financial planners in providing virtual services and developing effective financial planner-client relationships. At the foundation of the model is technology-use preconditions, which identifies the prerequisites for participation in virtual sessions.

Professionals and clients may have wide variation in these preconditions, and professionals should assess whether clients meet the preconditions prior to offering virtual services. The three levels of the pyramid represent factors correlated with effective financial practices (Sharpe et al. 2007). The pyramidion (the uppermost portion of the pyramid) captures skills and techniques—representing how technology will influence the essential knowledge and practices used by a financial planner. Financial planners must attend to how technology changes the psychological and physical environment of financial planning sessions, and the overall effectiveness of the meeting. How well a professional is able to use these skills and techniques is dependent upon the quality of the professional-client relationship. Professionals must consider how technology-mediated communication influences the strength of the financial planner-client relationship. Additionally, clients’ comfort and level of technological competency could influence their ability to connect with the financial planner. At the base of the pyramid, the professional’s way of being describes how a professional’s attitude toward polymedia (their way of being in virtual interactions) influences their ability to connect with their client and offer quality virtual services. Finally, running vertical to the pyramid and intersecting with technology-use preconditions, client confidentiality and cautions is how virtual services increase potential ethical and legal issues.

Moving forward, the technology-integrated Therapeutic Pyramid model and each of these best practices will need to be developed and empirically tested. Until then, borrowing from the mental health literature will aid in applying virtual practices to financial planning—a client-centered profession. Integrating the Therapeutic Pyramid (Fife et al. 2014) and the theory of polymedia (Madianou and Miller 2013) recognizes the types of media that are used when working with clients and how these media facilitate interpersonal communication to develop and maintain the professional-client relationship and the professional’s way of being. Through engaging with clients—not only via teleconferencing but also via phone, emails, and webinars—a sense of permeance in clients’ lives may enhance the therapeutic alliance (Madianou and Miller 2013). Together, these two theories offer financial planning professionals insights and considerations for offering virtual services that span across the theoretical domains of skills and techniques, the professional-client relationship, and the professional’s way of being.

References

Achenbach, Joel. 2020. “Coronavirus Is Harming the Mental Health of Tens of Millions of People in U.S., New Poll Finds.” The Washington Post. Available at www.washingtonpost.com/health/coronavirus-is-harming-the-mental-health-of-tens-of-millions-of-people-in-us-new-poll-finds/2020/04/02/565e6744-74ee-11ea-85cb-8670579b863d_story.html.

Arellano, Evelyn. 2020. “Power Dynamics and Inclusion in Virtual Meetings.” Aspiration Tech. Available at aspirationtech.org/files/AspirationPowerDynamicsAndInclusionInVirtualMeetings.pdf.

Asay, Ted P., and Michael J. Lambert. 1999. “The Empirical Case for the Common Factors in Therapy: Quantitative Findings.” In The Heart and Soul of Change: What Works in Therapy edited by M. A. Hubble, B. L. Duncan, and S. D. Miller (pages 23–55). Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association.

Asebedo, Sarah, and Emily Purdon. 2018. “Planning for Conflict in Client Relationships.” Journal of Financial Planning 31 (10): 48–56.

Assari, Shervin. 2019. “Race, Depression, and Financial Distress in a Nationally Representative Sample of American Adults.” Brain Sciences 9 (2): 1–13.

Bareket-Bojmel, Liad, Golan Shahar, and Malka Margalit. 2020. “COVID-19-Related Economic Anxiety is as High as Health Anxiety: Findings from the USA, the UK, and Israel.” International Journal of Cognitive Therapy May: 1–9.

Bischoff, Richard, Cody S. Hollist, Craig W. Smith, and Paul Flack. 2004. “Addressing the Mental Health Needs of Rural Underserved: Findings from a Multiple Case Study of a Behavioral Telehealth Project.” Contemporary Family Therapy 26 (2): 179–198.

Bohannon, Leanne S., Andrew M. Herbert, Jeff B. Pelz, and Esa M. Rantanan. 2013. “Eye Contact and Video-Mediated Communication: A Review.” Displays 34 (2): 177–185.

Bridges, Sarah, and Richard Disney. 2010. “Debt and Depression.” Journal of Health Economics 29 (3): 388–403.

Britt, Sonya, and John Grable. 2012. “Your Office May be a Stressor: Understand How the Physical Environment of Your Office Affects Financial Counseling Clients.” The Standard Newsletter from AFCPE 30 (2): 5.

Buber, Martin. 1958. I and Thou (2nd ed., R. G. Smith, Trans.). New York, N.Y.: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

Chaffin, Charles R., and Jonathan J. Fox. 2018. In Client Psychology, edited by Charles Chaffin. Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley & Sons: 1–9.

Cleary, Patrick. 2018. “Building The Five Pillars Of SEC Cybersecurity Requirements As A (Registered) Investment Adviser.” Kitces.com. Available at www.kitces.com/blog/sec-cybersecurity-requirements-for-registered-investment-advisors-rias/.

Cohen, Sheldon. 1994. “Perceived Stress Scale.” North Ottawa Wellness Foundation. Available at www.northottawawellnessfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/PerceivedStressScale.pdf.

D’Aniello, Carissa, and Stephen T. Fife. 2020. “A 20-Year Review of Common Factors Research in Marriage and Family Therapy: A Mixed Methods Content Analysis.” Journal of Marital and Family Therapy 46 (4): 701–718.

Davis, Sean D., and Alexander L. Hsieh. 2019. “What Does It Mean to Be a Common Factors Informed Family Therapist?” Family Process 58 (3): 629–640.

Dubofsky, David, and Lyle Sussman. 2009. “The Changing Role of the Financial Planner Part 1: From Financial Analytics to Coaching and Life Planning.” Journal of Financial Planning 22 (8): 48–57.

Engelberg, Elisabeth, and Lennart Sjöberg. 2006. “Money Attitudes and Emotional Intelligence.” Journal of Applied Social Psychology 36 (8): 2,027–2,047.

Fife, Stephen T. 2015. “Martin Buber’s Philosophy of Dialogue and Implications for Qualitative Family Research.” Journal of Family Theory & Review 7 (3): 208–224.

Fife, Stephen T., Jason B. Whiting, Kay Bradford, and Sean Davis. 2014. “The Therapeutic Pyramid: A Common Factors Synthesis of Techniques, Alliance, and Way of Being.” Journal of Marital and Family Therapy 40 (1): 20–33.

Fosslien, Liz, and Mollie West Duffy. 2020. “How to Combat Zoom Fatigue.” Harvard Business Review.

Frisch, Bob, and Cary Greene. 2020. “What It Takes to Run a Great Virtual Meeting.” Harvard Business Review.

Grable, John. 2017. “Optimal Design of a Financial Advisor’s Office: Insights from the Financial Planning Performance Lab.” Nerd’s Eye View Blog. Available at www.kitces.com/blog/scientific-interior-design-financial-advisory-office-planning-performance-lab-grable/.

Grable, John E., and Joseph W. Goetz. 2017. Communication Essentials for Financial Planners: Strategies and Techniques. Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley and Sons.

Grady, Brian, Kathleen Mary Myers, Eve-Lynn Nelson, Norbert Belz, Leslie Bennett, Lisa Carnahan, Veronica B. Decker et al. 2011. “Evidence-Based Practice for Telemental Health.” Telemedicine and e-Health 17 (2): 131–148.

Greenson, Ralph R. 2008. “The Working Alliance and the Transference Neurosis.” The Psychoanalytic Quarterly 77 (1): 77–102.

Henebry, Bobby. 2020. “Your Digital Presence Is Being Tested in a Social Distancing World.” Journal of Financial Planning 33 (5): 36–38.

Hertlein, Katherine M., Markie L. C. Blumer, and Jennifer H. Mihaloliakos. 2014. “Marriage and Family Counselors’ Perceived Ethical Issues Related to Online Therapy.” The Family Journal: Counseling and Therapy for Couples and Families 23 (1): 5–12.

Hilty, Donald M., Daphne C. Ferrer, Michelle Burke Parish, Barb Johnston, Edward J. Callahan, and Peter Mackinlay Yellowlees. 2013. “The Effectiveness of Telemental Health: A 2013 Review.” Telemedicine and e-Health 19 (6): 444–454.

Horvath, Adam O. 2001. “The Alliance.” Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training 38 (4): 365–372.

Hunt, Katherine H. M., Mark Brimble, and Brett Freudenberg. 2011. “Determinants of Client-Professional Relationship Quality in the Financial Planning Setting.” Australasian Accounting Business and Finance Journal 5 (2): 69–100.

Jaffe, Dennis T., and James Grubman. 2011. “Core Techniques for Effective Client Interviewing and Communication.” Journal of Financial Planning (Between the Issues).

Klingaman, Elizabeth A., Deborah R. Medoff, Stephanie G. Park, Clayton H. Brown, Lijuan Fang, Lisa B. Dixon, Samantha M. Hack, Stephanie L. Tapscott, Mary Brighid Walsh, and Julie A. Kreyenbuhl. 2015. “Consumer Satisfaction with Psychiatric Services: The Role of Shared Decision Making and the Therapeutic Relationship.” Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 38 (3): 242.

Kornegay, Susan, and Adam Kornegay. 2019. “Mastering the Stay-in-Touch Communication.” Journal of Financial Planning 32 (7): 21.

Lever, Suzanne and Brian Oten. 2020. “Professional Responsibility in a Pandemic.” North Carolina Bar. Available at www.ncbar.gov/news-publications/news-notices/2020/04/professional-responsibility-in-a-pandemic/.

Luxton, David D., Eve-Lynn Nelson, and Marlene M. Maheu. 2016. A Practitioner’s Guide to Telemental Health: How to Conduct Legal, Ethical, and Evidenced Based Telepractice. Washington, D.C.: APA.

Madianou, Mirca, and Daniel Miller. 2013. “Polymedia: Towards a New Theory of Digital Media in Interpersonal Communication.” International Journal of Cultural Studies 16 (2): 169–187.

Maheu, Marlene, M. Drude, Kenneth Hertlein, Ruth Lipschutz, Katherine Wall, and Donald M. Hilty. 2018. “Correction To: An Interprofessional Framework for Telebehavioral Health Competencies.” Journal of Technology in Behavioral Science 3 (2): 108–140.

Myers, Kathleen, and Carolyn L Turvey, eds. 2013. Telemental Health: Clinical, Technical, and Administrative Foundations for Evidence Based Practice. Waltham, Mass.: Elsevier

Norwood, Carl, Nima G. Moghaddam, Sam Malins, and Rachel Sabin Farrell. 2018. “Working Alliance and Outcome Effectiveness in Videoconferencing Psychotherapy: A Systematic Review and Noninferiority Meta Analysis.” Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy 25 (6): 797–808.

Osterland, Andrew. 2020. “Financial Advisors Face New Challenges in the Way They Manage Workflow, Communicate with Co-Workers and Clients.” CNBC. Available at www.cnbc.com/2020/05/18/financial-advisors-face-new-challenges-in-the-way-they-manage-workflow.html.

Pickens, Jaclyn Cravens, Neli Morris, and David J. Johnson. 2020. “The Digital Divide: Couple and Family Therapy Programs’ Integration of Teletherapy Training and Education.” Journal of Marital and Family Therapy 46 (2): 186–200.

Prossack, Ashira. 2020. “How To Host Virtual Meetings That Truly Engage Participants.” Forbes. Available at www.forbes.com/sites/ashiraprossack1/2020/04/30/how-to-host-virtual-meetings-that-truly-engage-participants/?sh=254c1fff524b.

SEC. 2015. “Cybersecurity Guidance.” Last modified April 2015, www.sec.gov/investment/im-guidance-2015-02.pdf.

SEC. 2016. “Business Continuity Planning for Registered Investment Companies.” Last modified June 2016, www.sec.gov/investment/im-guidance-2016-04.pdf.

Sensenig, Derek, J., Brian Walsh, Ives Machiz, Nicolas Stanley, Matthew Russell, and Megan McCoy. 2020. “Utilizing What We Know About Tele-Mental Health in Tele-Financial Planning: A Systematic Literature Review.” Journal of Financial Planning 33 (9): 48–58.

Sharpe, Deanna L., Carol Anderson, Andrea White, Susan Galvan, and Martin Siesta. 2007. “Specific Elements of Communication That Affect Trust and Commitment in the Financial Planning Process.” Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning 18 (1): 1–17.

Sheils, Rebecca, Adam Tucker, Brad Fox, and Richard Dunkerley. 2013. “Connecting with Clients Solving the Communication Matrix for Financial Advice Practices.” Association of Financial Advisers White Paper.

Simpson, Susan G., and Corinne L. Reid. 2014. “Therapeutic Alliance in Videoconferencing Psychotherapy: A Review.” Australian Journal of Rural Health 22 (6): 280–299.

Smarsh. 2021. “Enable Unified Compliance and E-Discovery Workflows Across All Your Business Communications.” www.smarsh.com/channel/zoom-us/.

Sprenkle, Douglas H., and Adrian J. Blow. 2004. “Common Factors and Our Sacred Models.” Journal of Marital and Family Therapy 30 (2): 113–129.

Springer, Paul R., Adam Farero, Richard J. Bischoff, and Nathan C. Taylor. 2016. “Using Experiential Interventions with Distance Technology: Overcoming Traditional Barriers.” Journal of Family Psychotherapy 27 (2): 148–153.

Sweet, Elizabeth, Arijit Nandi, Emma K. Adam, and Thomas W. McDade. 2013. “The High Price of Debt: Household Financial Debt and Its Impact on Mental and Physical Health.” Social Science & Medicine 91: 94–100.

Tam, Tony, Joseph A. Cafazzo, Emily Seto, Mary Ellen Salenieks, and Peter G. Rossos. 2007. “Perception of Eye Contact in Video Teleconsultation.” Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare 13 (1): 35–39.

Tharp, Derek. T. 2018. “The Behaviorally-Enlightened Fiduciary: Addressing Moral Dilemmas through a Decision-Theoretic Model of Moral Value Judgment.” Journal of Personal Finance 17 (1): 69–85.

Tharp, Derek. T. 2020. “Potential Consumer Harm Due to Regulation on Financial Advisory Communication in the FinTech Age.” Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning 31 (1): 146–161.

Timulak, Ladislav. 2007. “Identifying Core Categories of Client-Identified Impact of Helpful Events in Psychotherapy: A Qualitative Meta-Analysis.” Psychotherapy Research 17 (3): 205–314.

Wampold, Bruce, and Zac E. Imel. 2015. The Great Psychotherapy Debate: The Evidence for What Makes Psychotherapy Work Second Edition. New York, N.Y.: Routledge.

Wan, William. 2020. “The Coronavirus Pandemic Is Pushing America into a Mental Health Crisis.” The Washington Post. Available at www.washingtonpost.com/health/2020/05/04/mental-health-coronavirus/.

Whiting, Jason. B., Megan M. Oka., and Stephen T. Fife. 2012. “Appraisal Distortions and Intimate Partner Violence: Gender, Power, and Interaction.” Journal of Marital and Family Therapy 38: 133–149.

Citation

Archuleta, Kristy L., Sarah D. Asebedo, Dorothy B. Durband, Stephen Fife, Megan R. Ford, Blake T. Gray, Meghaan R. Lurtz, Megan McCoy, Jaclyn Cravens Pickens, and Gerald “Jerry” Sheridan. “Facilitating Virtual Client Meetings for Money Conversations: A Multidisciplinary Perspective on Skills and Strategies for Financial Planners.” Journal of Financial Planning 34 (4): 82–101.