Journal of Financial Planning: August 2017

Yuanshan Cheng, Ph.D., is an assistant professor of finance in the Department of Accounting, Finance, and Economics at Winthrop University.

Chris Browning, Ph.D., is an assistant professor and the co-director of undergraduate programs in the Department of Personal Financial Planning at Texas Tech University.

Philip Gibson, Ph.D., CFP®, is an assistant professor of finance in the Department of Accounting, Finance, and Economics at Winthrop University.

Executive Summary

- This study explored how various types and frequencies of communication relate to client satisfaction, trust, and commitment. Results indicate that clients were generally more satisfied when they received higher frequencies of investment-related educational communications, greeting cards, personal notes, and scheduled meetings.

- Increased frequencies of investment-related educational communications were positively associated with the likelihood of continuing to use the planner in the future and the percentage of assets managed by the planner. Greater frequencies of non-investment-related educational communications were associated with a larger number of referrals.

- Greeting cards and personal notes were found to be more relevant than non-investment-related educational communications when building client satisfaction and trust. The overuse of interest and hobby communications was found to result in lower levels of satisfaction, trust, and commitment.

- Scheduled meetings were positively and significantly associated with higher levels of satisfaction, trust, and commitment across all domains. The value of this type of communication appeared to top out at approximately four scheduled meetings per year.

Financial advice is complex. Consumers oftentimes lack the financial sophistication to make complicated financial decisions (Lusardi and Mitchell 2007; Lusardi, Mitchell, and Curto 2010). When the sophistication to make quality financial decisions is lacking, consumers can either choose to invest in the human capital that will lead to improved decision-making or rent the human capital of an expert. The decision to rent the human capital of an expert leads to demand for financial planners in the marketplace.

While this seems logical and intuitive, it highlights a common concern among planners: if clients lack the sophistication to make complex financial decisions, how will they recognize the value from complex planning? If clients cannot easily recognize value, how then can planners communicate value in a way that leads to client satisfaction, trust, and committed client relationships? As the marketplace becomes more commoditized—especially with regard to portfolio management—financial planners must develop scalable platforms to address these issues.

This study considered the importance of communication. In a market where goods and services are opaque, or quality is difficult to verify without sufficient knowledge and understanding, consumers are forced to rely on characteristics of an engagement that are easy to evaluate. Instead of relying on concrete assessments of value, consumers oftentimes rely on feelings of satisfaction and trust. In other words, people focus on relationships, and relationships are in large part built through communication.

Frequent and consistent communication is a tool that allows clients to perceive planner value and trustworthiness. Regular communication is also beneficial for planners, because it enables them to better understand their clients’ values and goals, and identify changing household demographics and new information that may affect their clients’ service needs.

This study evaluated the impact of educational (investment- and non-investment-related) and non-educational communication (greeting cards, interests, hobbies, and notes) at varying frequencies to measure how these communications affected client satisfaction, trust, and commitment. The results indicate that communication was valued and provide evidence that specific communication types were associated with increased levels of satisfaction, trust, referrals, and long-term committed client relationships.

Literature Review

Many households turn to financial planners for guidance to achieve financial success, with considerable evidence that planners add value to the decision-making process. Hung et al. (2008) found that among those who made investment purchases, more than 70 percent consulted a financial planner before the purchase was made. Jones, Lesseig, and Smythe (2005) found that planners played a critical role in highlighting important information in the mutual fund selection process. And Chalmers and Reuter (2010) found that investors working with financial planners tended to have better allocated and more diversified portfolios.

Although the evidence is positive, it is only meaningful if clients attach value to these outcomes. If clients are unable to make these connections, it may be beneficial for planners to consider alternative means of establishing their worth.

The value of communication has been well documented in the literature. Darby and Karni (1973) and Zeithaml (1981) found that professional services, such as financial and legal advice, were difficult for consumers to evaluate due to a lack of technical knowledge and expertise. For these types of professional services, Sharma and Patterson (1999) argued that it was essential to have a high degree of interaction and interpersonal communication to enhance delivery and strengthen relationships.

Vargo and Lusch (2004) highlighted the importance of a co-production model in the retail marketing industry, where co-production can be represented by collaboration between the planner and client to define and create value (Littlechild 2014). Auh, Bell, McLeod, and Shih (2007) confirmed that the co-production model led to higher degrees of perceived value because customers were able to participate in the creation process through customer-planner communication.

Considering five communication tasks based on the guidelines of CFP Board’s Financial Planning Practice Standards, Anderson and Sharpe (2008) found that communication was important when building trust and commitment in the client-planner relationship. Additionally, Swift and Littlechild (2015) provided considerations for how to develop and implement a communication plan to enhance client trust.

This study sought to quantify the value of various types of communication and their frequencies when interacting with clients. The primary focus was placed on two types of communication—educational and non-educational—and their frequencies to determine how communication can be used to impact client satisfaction, trust, and commitment in the client-planner relationship. The results provide specific guidance on how planners can implement communication strategies in their practices to create value and strengthen client relationships.

Hypotheses

In the complex market of financial advice, it is theorized that communications can serve as an accessible metric for assessing planner quality. As a result, this study hypothesized that: (1) clients’ satisfaction with their planner was a function of the types and frequencies of communications they received; (2) increased levels of satisfaction were significantly related to increased levels of client trust; and (3) higher trust was significantly related to more committed client relationships.

Methodology

Data. The data used for this study came from the Adviser Impact Survey. Adviser Impact was a financial consulting company that provided services to financial planning companies worldwide. The survey data in this study consisted of 1,229 clients of U.S. financial planning companies in 2014. The respondents were working with at least one financial planner and had investable assets of more than $50,000 at the time of the interview. Respondents who did not answer communication, satisfaction, trust, or investable asset questions were deleted. That left a final sample size of 1,088, which was used for the descriptive statistics and the regression analyses.

Dependent variables. To measure satisfaction, client-reported satisfaction levels were used. Clients were asked about their satisfaction in four areas: (1) keeping track and being focused on the long-term; (2) selecting investments with the best chance of a high return; (3) full understanding of personal goals and dreams; and (4) clear understanding of personal values.

Satisfaction was measured on a five-point Likert scale with responses ranging from completely dissatisfied to completely satisfied. Trust was measured on a three-point Likert scale with responses ranging from low to high.

Five questions were used to measure the quality of commitment. The first was whether the client provided referrals in the last 12 months. The second question asked clients to state how many referrals they provided in the last 12 months.

The third question measured the reported likelihood of a client staying with their current planner. Clients reported their preference for staying with their current planner by choosing from the following:

“I have not considered switching to a new adviser.”

“I have considered switching to a new adviser but have not taken any steps to do so.”

“I have considered switching to a new adviser and have made some preliminary inquiries.”

“I have considered switching to a new adviser and have taken some steps to do so.”

A binary variable was created and those who had not considered switching were coded as 1 and all others were coded as 0.

The fourth question was: “How likely are you to continue using your financial adviser to manage your financial plan or portfolio in the next 12 to 24 months?” Clients chose from not at all likely; not likely; neutral; likely; and extremely likely. For this analysis, the question was recoded into a three-scale ordered variable due to a lack of responses that were less favorable than “neutral.” The updated categories included less than likely; likely; and extremely likely.

The fifth measurement asked: “Today, what percentage of your household investable assets are managed by your primary financial planner, including all mutual funds, stocks, bonds, 401(k), IRA, and other retirement accounts (excluding real estate)?” Clients chose from the following options: less than 10 percent of my assets; 10 to 24 percent of my assets; 25 to 49 percent of my assets; 50 to 74 percent of my assets; 75 to 99 percent of my assets; and 100 percent of my assets.

Three groups were created based on the percentage of assets managed by the primary planner: less than 24 percent; 25 percent to 74 percent; and more than 75 percent. By structuring the variable in this way, a more traditional distribution was created, where the less than 24 percent group represented the left tail of the distribution, the 25 to 74 percent group represented the middle of the distribution, and the 75 percent or more group represented the right tail of the distribution. This provided the opportunity to observe how satisfaction and trust impacted the level of assets managed in reference to a more normal distribution.

Independent variables. Five variables were used to measure communication. These variables measured the reported frequencies of different types of communications from financial planners, including: (1) educational communications focused on investments, markets, or other economic topics; (2) educational communications not related to investments, but more related to topics of specific client interest (e.g., Social Security, health care reform, etc.); (3) communications on topics related to interests or hobbies (e.g. wine, golf, etc.); (4) greeting cards or personal notes recognizing a special event for the client or their family; and (5) scheduled client meetings, either face-to-face or over the phone.

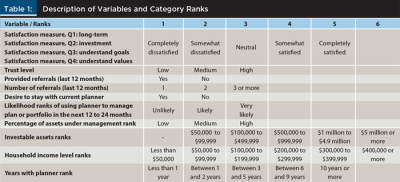

Additional control variables used in the study included client tenure with their planner, wealth, income, and marital status. These variables were stated as categorical questions in the survey. For the purpose of this analysis these variables were coded into ordered ranks. See Table 1 for a summary of how these variables were measured in the analysis.

Results

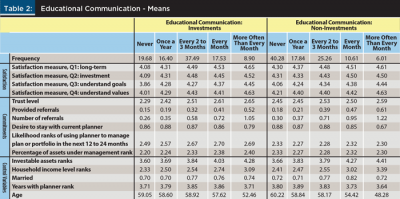

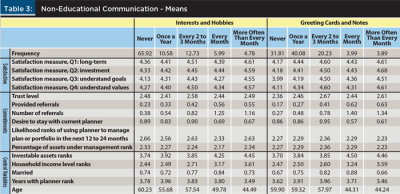

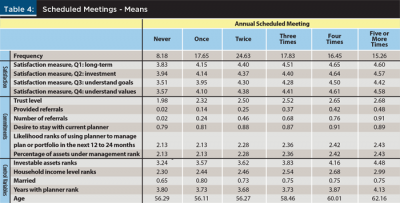

Descriptive results. Tables 2, 3, and 4 provide descriptive statistics for the relationship between the communication variables and the dependent variables. Average levels of satisfaction, trust, and commitment are shown based on the communication type and frequency, with higher numbers being more favorable than lower numbers.

The first rows of Tables 2, 3, and 4 show the percentage of respondents who received communications at varying frequencies. Table 2 shows that 19.68 percent of clients never received investment-related educational communications, and that 8.9 percent of respondents received investment-related educational communications more often than once a month. In addition, 40.28 percent of respondents reported never receiving non-investment-related educational communications, while 6.01 percent reported receiving these types of communications more frequently than once a month.

With regard to both investment- and non-investment-related educational communications, results show that the frequency of educational communication was positively associated with satisfaction levels (in all four satisfaction domains) and trust. Investment-related communication frequency was also shown to be positively associated with the commitment variables, while non-investment-related communication frequency was positively related to referrals, but not the other measures of commitment.

Table 3 shows that 65.92 percent of clients never received communications related to interests and hobbies, and that 4.78 percent of respondents received these types of communications more often than once a month. In addition, 31.81 percent of respondents reported never receiving greeting cards or notes, while 3.89 percent reported receiving these types of communications more frequently than once a month.

With regard to communications related to interests and hobbies, the results showed that the frequency of communication had little relation to the clients’ satisfaction with long-term planning and investment management. There was some relation between interest and hobby communications and clients’ satisfaction from understanding goals and values, but this relationship peaked when these types of communications were provided every two to three months. Interest and hobby communication frequencies were also shown to be positively associated with referrals, but not the other measures of commitment.

Results for greeting cards and notes showed that the frequency of this type of communication had some positive relation to all four measures of client satisfaction, with the maximum value achieved at a frequency of about every two to three months. Greeting cards and notes were also shown to be positively associated with referrals, but not the other measures of commitment.

Table 4 shows that 8.18 percent did not have any meetings with their planner in the survey year, and that 15.26 percent of respondents met with their planner more than five times. With regard to the number of meetings per year, the results showed a positive relationship between the number of meetings and satisfaction levels (in all four satisfaction domains), trust, and client commitment.

Multivariate results. Ordered logistic regressions were used to test the impact of planner communication on client satisfaction, trust, and commitment. This modeling was appropriate because it allowed for a categorical dependent variable where the categories had a natural ordered rank. Separate regressions were run for each of the dependent variables described previously.

The first set of analyses aimed to confirm the positive relationship between communications and client satisfaction. After controlling for the tenure of the client-planner relationship and other demographic variables thought to be related to the client-planner relationship, higher frequencies of educational communications about investments, sending greeting cards and personal notes, and more scheduled meetings were significantly associated with higher satisfaction levels for all four satisfaction domains. The results on non-investment-related educational communication and communications related to interests and hobbies were not found to be significant.

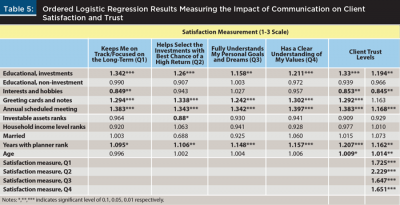

The second set of analyses evaluated the impact of both communication and client satisfaction on client trust. When looking at the results presented in Table 5, the first column under the “Client Trust Levels” heading reports results from the model where the satisfaction variables were omitted; the second column reports results where the satisfaction variables were included in the analysis.

The results shown in the first column provide evidence that higher frequencies of investment-related educational communication, greeting cards and notes, and scheduled meetings were associated with higher levels of trust. The results of this regression also provide evidence that increased communications related to interest and hobbies were associated with lower levels of client trust. Because the quality of financial advice is difficult to verify, an overuse of these types of communication may create suspicion from the client related to the planner’s motives.

The results shown in the second column show that even after controlling for satisfaction measurements, higher frequencies of investment-related educational communication and scheduled annual meetings were associated with increased trust. The results also showed that all satisfaction measures were significant predictors of trust, and that the inclusion of those variables weakened the statistical impact of the communication variables. This result does not suggest that communication played a diminished role in building client trust. Rather, it supports the first set of regression results that showed a relationship between communication and satisfaction and highlights the importance of the communication/satisfaction relationship when building client trust.

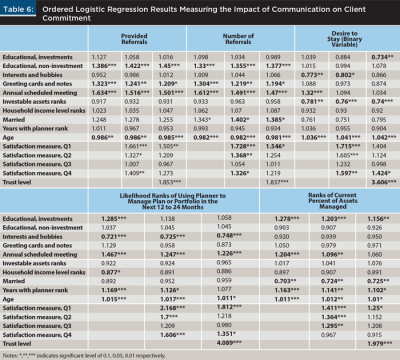

The final set of analyses shown in Table 6 explored the impact of communication, satisfaction, and trust on client commitment. When looking at the results presented in Table 6, satisfaction and trust variables were omitted in the first column, the second column reports results from the model where only the trust variables were omitted, and the third column reports results from the full model.

When considering the number of referrals as a proxy for commitment, results showed that increased frequencies of non-investment-related educational communications, greeting cards and notes, and scheduled meetings were positively related to the number of referrals. This result held even after including the satisfaction and trust variables in the model.

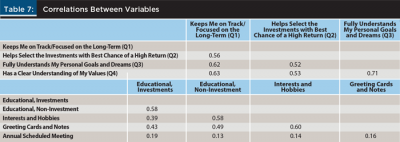

Results also showed that client satisfaction was positively related to the number of referrals, but that the effects of satisfaction were weakened when trust was included in the model. This effect was consistent across all measures of client commitment, highlighting again the correlation between communication, satisfaction, and trust and their interrelated importance to building long-term client relationships. Correlations between the variables are reported in Table 7. No significant issues with multicollinearity were detected.

Other results of interest related to client commitment include: (1) the negative relationship between interests and hobby communications and the likelihood of using the planner over the next 12 to 24 months; and (2) the strong positive relationship between scheduled meeting frequency and all measures of commitment, even after controlling for satisfaction and trust.

Discussion and Financial Planning Implications

As complexity and the role of technology continue to increase in the financial marketplace, clients are faced with the difficult task of assessing quality in the client-planner relationship, while planners are faced with the task of communicating their value. A point of concern for planners should be the process by which clients assess satisfaction with service. Because many individuals lack the financial sophistication to measure quality (Mullainathan, Noeth, and Schoar 2012) they may fail to attach value to high-quality expert advice. This is due to the credence nature of financial advice and individuals’ inability to assess advice quality at any point during the client-planner relationship. As a result, clients may rely on more salient characteristics of the engagement, such as satisfaction and trust, to assess quality. As such, the financial planner has the primary responsibility of developing and instilling these attributes in the client-planner relationship. This study explored the value of communication as a means of accomplishing this objective and sought to quantify the value of various types of communication and their frequencies when interacting with clients. Focus was given to both the type and frequency of communication to determine how communication could be used to impact client satisfaction, trust, and commitment in the client-planner relationship.

The results indicated that higher frequencies of investment-related educational communications, greeting cards and personal notes, and annual scheduled meetings were significantly associated with higher satisfaction levels, higher levels of trust, and increased client commitment. These results supported the hypotheses that communication is positively related to satisfaction, higher satisfaction levels are associated with higher trust levels, and that trust is associated with more committed client-planner relationships.

Beyond the importance of the statement above, insight is provided into how different types of communication could be used by planners in practice to build and strengthen their client relationships.

Scheduled meetings are very important. Higher numbers of scheduled meetings were positively and significantly associated with higher levels of satisfaction, trust, and commitment across all domains. That said, the value of this type of communication appeared to be maximized at approximately four scheduled meetings per year (see Table 4).

Increased frequencies of investment-related educational communications were positively associated with the likelihood of continuing to use the planner in the future and the percentage of assets managed by the planner. This suggests that clients may hold the traditional notion that the planner’s main role in the planning process is to manage the investment portfolio. Providing clients with investment-related educational content may satisfy this notion and give clients increased confidence in the planner’s ability to meet their ongoing needs.

The value of greeting cards and personal notes should not be overlooked. These types of communications were found to be more relevant than non-investment-related educational communications (e.g. Social Security, health care reform, etc.) when building client satisfaction and trust. The increased use of these types of communications was also found to be significantly associated with the number of client referrals.

Use caution when incorporating interest and hobby communications into the communication platform. Results suggest that the overuse of these types of communications can have a negative impact on satisfaction, trust, and commitment.

Increased frequencies of non-investment-related educational communications were associated with a higher number of referrals. These types of communications may represent less technical pieces of information that clients can confidently share with their peers. This may also broaden the scope of the engagement in the client’s mind and serve as bragging points when discussing the value of their planner among their peers.

A possible limitation of this study is the impact that the tenure of the client-planner relationship might have on the association between the different forms of communication and their relationship to client satisfaction, trust, and commitment. However, findings in Table 5 show widespread significance of the communication variables in relation to both satisfaction and trust, even after controlling for the length of the client-planner relationship. Table 6 also indicates that many of the communication variables were significantly related to client commitment, even after controlling for years with the planner, satisfaction, and trust. This indicates the importance of the communication variables in the model and gives some assurance that their impact on client satisfaction, trust, and commitment are being captured.

By observing clients’ reactions to multiple types of communication, this study provides insight that financial planners can use to improve their services and strengthen their client relationships. This also highlights a potential concern in the financial planning profession: if planners are able to use communication to create client satisfaction, trust, and commitment, there is an opportunity and incentive for low-quality service providers to enter the financial advice market and use various communication techniques to create perceived value among consumers. Given these considerations and the client communication demands that will result from an ever-evolving demographic of the client pool (Grubman and Jaffe 2016), ongoing research that assesses the value of communication in the client-planner relationship will be relevant and important to both the practice of financial planning and the successful growth of the profession.

References

Anderson, Carol, and Deanna L. Sharpe. 2008. “The Efficacy of Life Planning Communication Tasks in Developing Successful Planner-Client Relationships.” Journal of Financial Planning 21 (6): 66–77.

Auh, Seigyoung, Simon J. Bell, Colin S. McLeod, and Eric Shih. 2007. “Co-Production and Customer Loyalty in Financial Services.” Journal of Retailing 83 (3): 359–370.

Chalmers, John, and Jonathan Reuter. 2010. “What Is the Impact of Financial Advisers on Retirement Portfolio Choices and Outcomes?” National Bureau of Economic Research working paper w18151.

Darby, Michael R., and Edi Karni. 1973. “Free Competition and the Optimal Amount of Fraud.” The Journal of Law and Economics 16 (1): 67–88.

Grubman, James, and Dennis T. Jaffe. 2016. “Becoming a Culturally Intelligent Financial Planner.” Journal of Financial Planning 29 (11): 30–33.

Hung, Angela A., Noreen Clancy, Jeff Dominitz, Eric Talley, Claude Berrebi, and Farrukh Suvankulov. 2008. “Investor and Industry Perspectives on Investment Advisers and Broker-Dealers.” Rand Institute for Civil Justice, available at sec.gov/news/press/2008/2008-1_randiabdreport.pdf.

Jones, Michael A., Vance P. Lesseig, and Thomas I. Smythe. 2005. “Financial Advisers and Mutual Fund Selection.” Journal of Financial Planning 18 (3): 64–70.

Littlechild, Julie. 2014. “The Future of Client Communication: Drive Engagement, Create Differentiation.” Journal of Financial Planning 27 (11): 26–30.

Lusardi, Annamaria, and Olivia Mitchell. 2007. “Baby Boomer Retirement Security: The Roles of Planning, Financial Literacy, and Housing Wealth.” Journal of Monetary Economics 52 (1): 205–224.

Lusardi, Annamaria, Olivia Mitchell, and Vilsa Curto. 2010. “Financial Literacy among the Young.” Journal of Consumer Affairs 44 (2): 358–380.

Mullainathan, Sendhil, Markus Noeth, and Antoinette Schoar. 2012. “The Market for Financial Advice: An Audit Study.” National Bureau of Economic Research working paper w17929.

Sharma, Neeru, and Paul G. Patterson. 1999. “The Impact of Communication Effectiveness and Service Quality on Relationship Commitment in Consumer, Professional Services.” Journal of Services Marketing 13 (2): 151–170.

Swift, Marie and Julie Littlechild. 2015. “Building Trust through Communication.” Journal of Financial Planning 28 (11): 28–32.

Vargo, Stephen L., and Robert F. Lusch. 2004. “Evolving to a New Dominant Logic for

Marketing.” Journal of Marketing 68 (1): 1–17.

Zeithaml, Valarie A. 1981. “How Consumers’ Evaluation Processes Differ Between Goods and Services.” In J.H. Donnelly and W. George (Eds.), Marketing of Services (pp. 186–190).

Chicago, IL: American Marketing Association.

Citation

Cheng, Yuanshan, Chris Browning, and Philip Gibson. 2017. “The Value of Communication in the Client-Planner Relationship.” Journal of Financial Planning 30 (8): 36–44.