Journal of Financial Planning: August 2025

NOTE: Please be aware that the audio version, created with Amazon Polly, may contain mispronunciations.

Executive Summary

- This study explores how personality traits influence annuity ownership among older Americans, addressing the long-standing annuity puzzle.

- Using data from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), probit regression analysis evaluates associations between the five-factor model personality traits and private annuity ownership.

- Conscientiousness is positively associated with annuity ownership, while openness, extraversion, and neuroticism are negatively associated.

- Financial, health, and sociodemographic factors also show significant relationships, including income, home equity, Social Security income, and education.

- Findings suggest that psychological profiles offer valuable insights for financial planners advising on retirement income strategies.

- Practical implications encourage integrating personality assessment into client engagement to better align annuity recommendations with individual retirement needs.

Dr. Preston Cherry is assistant professor of personal financial planning at the University of Wisconsin–Green Bay. His research focuses on financial psychology, retirement planning, and wealth alignment. He is also a practicing CFP® professional and frequent contributor to financial media and policy discussions.

Dr. Sarah Asebedo is associate professor of personal financial planning at Texas Tech University. Her research bridges financial planning and positive psychology, emphasizing behavior change, conflict resolution, and well-being in financial decision-making. She holds both CFP® certification and a Ph.D. in personal financial planning.

Dr. Blain Pearson is assistant professor of finance at Coastal Carolina University. His research explores retirement income strategies, annuity markets, and financial decision-making. He combines academic insight with a strong grounding in personal finance education and behavioral finance applications.

NOTE: Click on the images below for PDF versions.

JOIN THE DISCUSSION: Discuss this article with fellow FPA Members through FPA's Knowledge Circles.

FEEDBACK: If you have any questions or comments on this article, please contact the editor HERE.

Longevity risk—the possibility of outliving one’s retirement savings—has become an increasingly pressing challenge for Americans as life expectancy rises. Americans are living longer than previous generations, with life expectancy in the United States reaching 76.4 years as of 2022, despite a slight decline from the pandemic years (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] 2023). On average, individuals who reach age 65 can now expect to live an additional 18.9 years (National Center for Health Statistics [NCHS] 2023). The threat of extended retirement durations continues to grow, particularly as approximately 53 percent of Americans are expected to live to at least age 80, and nearly 35 percent are projected to reach age 85 (Arias, Tejada-Vera, and Ahmad 2022). Private annuities provide an important financial tool to address this risk, offering guaranteed lifetime income streams.

Despite rising life expectancies, retirement readiness remains a persistent challenge. According to the Federal Reserve’s 2022 Survey of Consumer Finances, the median retirement savings for U.S. households was $87,000, with the average balance at $333,940, highlighting significant disparities in retirement preparedness (Federal Reserve Board 2023). Furthermore, the 2023 Retirement Confidence Survey by the Employee Benefit Research Institute revealed that 33 percent of workers have less than $50,000 in savings and investments, and 14 percent have less than $1,000, underscoring widespread concerns about financial security in retirement (EBRI 2023). These financial concerns highlight the critical need for effective retirement income solutions to help individuals protect against financial uncertainty in later life.

Economic theory posits that rational individuals seek to maximize their utility under conditions of uncertainty (Von Neumann and Morgenstern 1947; Kahneman and Tversky 1979). Within this framework, assuming fair pricing, life annuities offer a mechanism for addressing longevity risk by converting lump-sum savings into guaranteed lifetime income streams (Brown 2007; Davidoff et al. 2005). Partial or full annuitization of retirement assets serves to optimize retirement income flows across uncertain life spans, providing both financial security and peace of mind for retirees.

Despite their theoretical benefits, annuity products remain underutilized, a phenomenon commonly called the annuitization “puzzle” (Benartzi, Previtero, and Thaler 2011), which has attracted significant research attention. Traditional economic models cannot fully explain the limited use of annuities, suggesting the need for broader perspectives.

Recent innovations in annuity product design, such as longevity insurance, seek to address the hesitation many individuals feel about fully annuitizing their wealth (Guillemette et al. 2016). These products aim to protect late-life income while preserving liquidity and flexibility earlier in retirement.

However, despite their theoretical benefits, annuity adoption remains limited, necessitating further exploration into behavioral, psychological, and sociodemographic factors influencing annuitization decisions.

Behavioral factors, including personality traits, may help explain annuitization decisions. This study investigates whether personality traits, specifically those in the five-factor model (openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism), are associated with annuity ownership among older Americans.

Beyond traditional economic models, emerging frameworks emphasize the role of psychological well-being, emotional satisfaction, and personal identity in shaping financial decisions during retirement. Cherry (2024) highlights that achieving financial harmony—aligning financial strategies with individual life values, emotions, and longevity expectations—is critical for comprehensive retirement planning. This broader perspective supports the need to investigate behavioral drivers, such as personality traits, influencing key decisions like annuity adoption.

By identifying psychological influences on annuity decisions, this research aims to bridge theoretical understanding with actionable insights for financial planners working to optimize client retirement income strategies.

Literature Review

Economic models, such as life cycle theory and consumer demand theory, suggest that full or partial annuitization can optimize retirement consumption by protecting against longevity risk. These models assume rational behavior, actuarially fair pricing, and perfect markets (Yaari 1965; Davidoff et al. 2005).

However, empirical evidence reveals limited private annuity demand, highlighting gaps between theory and behavior (Brown 2007). Behavioral explanations such as framing effects, loss aversion, and subjective mortality beliefs have been proposed to account for the annuity puzzle (Brown et al. 2008).

Personality psychology, particularly the five-factor model, offers a framework for understanding individual differences in financial decision-making. Traits such as conscientiousness and openness influence saving behavior, investment choices, and risk tolerance (Asebedo et al. 2019). Evidence suggests that personality traits, particularly conscientiousness, significantly shape lifetime earnings and retirement wealth accumulation (Duckworth and Weir 2010). These traits influence not only income-generating potential but also savings behavior and financial decision-making patterns that carry into retirement.

Recent research continues to highlight the relevance of personality traits in explaining key financial risk management decisions among older Americans. Cherry and Asebedo (2022a) found that specific traits within the five-factor model were significantly associated with the likelihood of owning private life insurance policies. Their study revealed that conscientiousness was positively associated with life insurance ownership, supporting the idea that organized, disciplined, and future-oriented individuals are more likely to adopt financial products that mitigate long-term risks.

Similarly, Cherry and Asebedo (2022b) demonstrated that personality traits influence long-term care financial preparation behaviors, with conscientiousness and agreeableness emerging as important predictors. These findings reinforce the broader role of personality in shaping risk perceptions and the proactive acquisition of financial instruments that secure retirement well-being. Together, these studies align with the present article’s objective by supporting the premise that conscientiousness—and personality more broadly—may influence another critical retirement planning behavior: the decision to purchase annuities to protect against longevity risk.

Building on this interdisciplinary literature, this study explores how personality traits influence older Americans’ annuity ownership decisions, expanding the behavioral dimension of annuity demand research.

Theory and Hypotheses Development

Life cycle theory posits that individuals seek to smooth consumption over their lifetime by accumulating assets during working years and decumulating them during retirement (Ando and Modigliani 1963). Annuities offer one possible solution for addressing lifespan uncertainty by providing guaranteed income. Personality traits, broadly defined as enduring patterns of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors that differentiate individuals (American Psychological Association [APA] 2022), offer valuable insight into these differences.

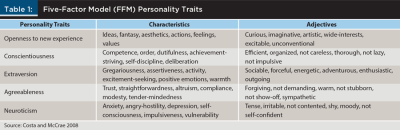

The five-factor model identifies key personality domains that shape behavior, including financial decision-making. Conscientiousness, for example, is linked to planning and goal achievement, while openness is associated with novelty-seeking and imagination (Costa and McCrae 2008).

Drawing from these theoretical frameworks, this study formulates hypotheses regarding the relationships between personality traits, financial and health factors, sociodemographic variables, and annuity ownership among older Americans.

Hypotheses

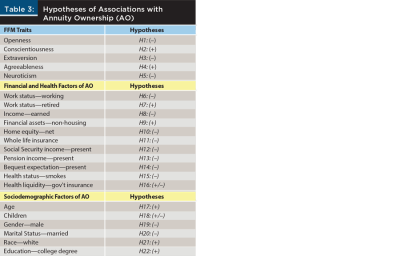

This study examines the relationship between personality traits and annuity ownership among older Americans. Openness to experience reflects imagination, broad interests, and a willingness to embrace new ideas (Costa and McCrae 2008). However, individuals high in openness may struggle to connect with their future selves or accurately forecast long-run outcomes, which may undermine financial decisions related to retirement income security (Hershfield et al. 2011). Although intellectual curiosity could support understanding complex financial products like annuities, prior research links openness to reduced saving behavior (Asebedo et al. 2019). Therefore, openness is expected to associate negatively with annuity ownership (H1).

Conscientious individuals tend to be organized, deliberate, and achievement-driven, aligning with long-term financial planning and risk mitigation behaviors (Costa and McCrae 2008). Given these traits, it is expected that conscientiousness will associate positively with annuity ownership (H2). Conversely, extraverts, who display tendencies for excitement-seeking and risk-taking (Costa and McCrae 2008), may experience conflict between their preference for stimulation and the risk-averse nature of annuity purchases, despite anticipating longer life spans (Agnew et al. 2008). Thus, extraversion is expected to associate negatively with annuity ownership (H3).

Individuals high in agreeableness exhibit traits such as trust and altruism (Costa and McCrae 2008), which may support partial annuitization strategies aimed at balancing retirement income with bequest motives. Therefore, it is expected that agreeableness will associate positively with annuity ownership (H4). In contrast, neurotic individuals often exhibit impulsivity and emotional vulnerability (Costa and McCrae 2008), characteristics that may undermine long-term financial planning. Consequently, it is expected that neuroticism will associate negatively with annuity ownership (H5).

Beyond personality, financial and health factors are also expected to influence annuity ownership. Work status is anticipated to play a role, with retirement compared to continued employment increasing exposure to longevity risk. As such, retired individuals are expected to associate positively with annuity ownership, while employed individuals are expected to associate negatively (H6, H7). Income level is also expected to influence annuitization decisions, as higher earned income can satisfy retirement consumption needs, reducing reliance on private annuities. Therefore, income is expected to associate negatively with annuity ownership (H8).

Financial assets may increase annuity ownership likelihood, as individuals with greater wealth often perceive longer life expectancy and may seek lifetime income protections (Agnew et al. 2008). Thus, financial assets are expected to associate positively with annuity ownership (H9). Home equity can be an alternative funding source for retirement shortfalls (Hanewald 2016), suggesting that home equity is expected to associate negatively with annuity ownership (H10). Similarly, whole life insurance provides liquidity and retirement security, potentially serving as a substitute for annuities. This leads to the expectation that whole life insurance ownership will associate negatively with annuity ownership (H11).

Existing sources of annuity-like income, such as Social Security and defined benefit pension plans, may reduce the demand for additional private annuitization (Dushi and Webb 2004). Therefore, both Social Security income (H12) and pension income (H13) are expected to associate negatively with private annuity ownership. Regarding bequest expectations, individuals who prioritize wealth transfer to heirs may be less inclined to fully annuitize their retirement assets. Thus, it is expected that the presence of bequest expectations will associate negatively with annuity ownership (H14).

Health status is another important consideration. Poor health, indicated by current smoking status, may reduce expected longevity and diminish the appeal of lifetime annuity products. Therefore, smoking is expected to associate negatively with annuity ownership (H15). Liquidity needs related to healthcare costs could also affect annuity decisions. Given that Medicare provides partial protection but still involves healthcare uncertainty, Medicare coverage compared to being uninsured is expected to have a significant, though directionally ambiguous, relationship with annuity ownership (H16).

Finally, sociodemographic factors are anticipated to impact annuity ownership. Age is expected to associate positively with annuity ownership, as older individuals face higher longevity risk (H17). The presence of children could influence retirement preferences and annuitization decisions, though the direction of the relationship remains unclear (H18). Gender differences in life expectancy suggest that males are less likely than females to own annuities (H19). Marital status may also matter, with marriage offering internal risk-pooling that reduces the need for private annuitization, leading to an expected negative association between marriage and annuity ownership (H20).

Racial differences in life expectancy inform expectations that Whites, compared to non-Whites, are more likely to own annuities due to greater longevity (Arias and Xu 2020) (H21). Lastly, higher levels of education are associated with greater financial literacy and retirement planning sophistication, leading to the expectation that individuals with a college degree are more likely to own annuities compared to those without a degree (H22).

Building on these theoretical expectations, the following section outlines the data source, sample construction, and analytical strategy used to examine the predictors of annuity ownership.

Methods

This study utilizes data from the 2020 wave of the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), a nationally representative, longitudinal panel survey of Americans over the age of 50, conducted by the University of Michigan with support from the National Institute on Aging (Health and Retirement Study, RAND HRS Longitudinal File 2024). The analytic sample consists of respondents aged 50 and older who completed the psychosocial leave-behind questionnaire during the 2016, 2018, and 2020 survey waves.

The initial dataset included 10,989 respondents aged 50 and older. The analytic sample was refined to include only respondents with non-missing responses on annuity ownership and complete data on financial, health, and psychosocial variables. Additionally, annuity ownership was identified using targeted follow-up questions within the HRS, which may have been administered to a subset of respondents depending on survey module participation. This yielded a final analytic sample of 388 annuity owners.

Core demographic, health, and financial variables were drawn from the RAND HRS Longitudinal File (2020 V2), while additional psychosocial and personality measures were supplemented using the RAND HRS Fat Files for the 2016, 2018, and 2020 waves (Health and Retirement Study, RAND HRS Fat Files 2024). These data sources allow for integrating detailed personality, wealth, and retirement-related measures to evaluate the relationship between psychological traits and annuity ownership decisions.

Personality traits were assessed using the Midlife Development Inventory (MIDI) Personality Scales, a validated instrument designed to measure the Big Five traits within the HRS psychosocial questionnaire (Lachman and Weaver 1997). Annuity ownership was assessed based on whether respondents reported owning private annuities or annuity-like products, excluding employer pensions and Social Security.

Control variables included income, financial assets, home equity, work status, health status (smoking), whole life insurance ownership, existing pension and Social Security income, bequest expectations, Medicare coverage, age, gender, marital status, children, race, and education.

Probit regression analysis was employed to estimate the probability of annuity ownership as a function of personality traits and control variables. Probit regression is used because the dependent variable, annuity ownership, is binary, requiring a model that appropriately estimates the probability of an event occurring.

This approach captures the nonlinear relationship between predictors and annuity ownership. It allows for the calculation of marginal effects, offering practical insights into how changes in personality traits and financial factors influence the likelihood of owning an annuity.

Descriptive Statistics and Results

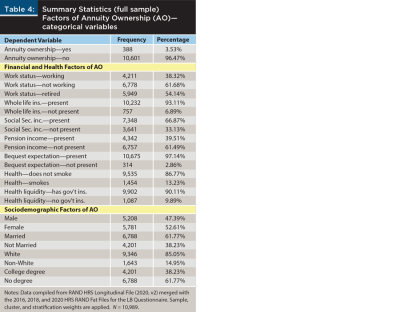

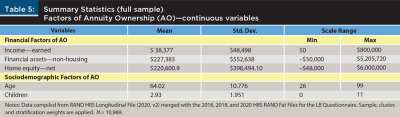

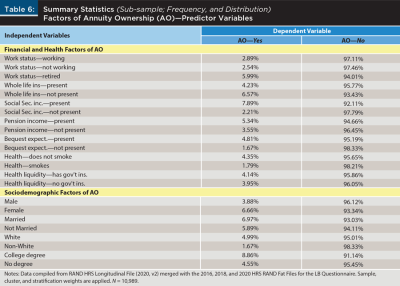

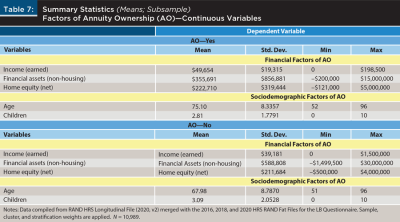

Descriptive statistics reveal that 3.4 percent of respondents reported owning a private annuity product. The average age of participants was 67 years, with 53 percent female and 47 percent male respondents. Approximately 85 percent of the sample identified as White, 9 percent as Black, and 6 percent as Hispanic or Other racial categories. Most respondents were retired (54 percent), with a substantial portion reporting Social Security and/or pension income.

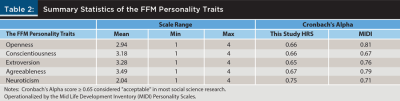

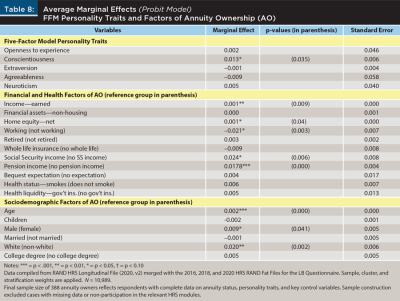

Probit regression analysis indicates that conscientiousness is associated with a 1.3 percentage point increase in the likelihood of annuity ownership (p = .035), supporting H2. Openness to experience, extraversion, and neuroticism were not statistically significant predictors of annuity ownership, providing no support for H1, H3, or H5. Agreeableness was also not significantly related to annuity ownership, contrary to H4.

Among financial and health factors, higher income, home equity, and existing Social Security income were significantly related to annuity ownership. Higher financial asset holdings were positively associated with annuity ownership, supporting H9. Current smoking was negatively associated with annuity ownership, supporting H15.

Sociodemographic factors, including older age, being White, and having a college education, were significantly associated with higher likelihoods of owning a private annuity, supporting H17, H21, and H22. Marital status and gender also showed significant effects consistent with the hypotheses.

Overall, the results support the expected relationships between conscientiousness, financial asset levels, age, and annuity ownership, while openness and neuroticism were negatively associated as hypothesized.

Discussion

The findings of this study expand understanding of the psychological dimensions influencing retirement planning decisions. Conscientiousness emerged as a strong positive predictor of annuity ownership, consistent with its established link to goal-oriented financial behavior.

The results indicate that individuals with higher levels of conscientiousness are significantly more likely to own a private annuity (Table 8). This finding is critical, as it underscores the central argument of this study: psychological traits, particularly conscientiousness, provide meaningful insight into real-world retirement income decisions.

Conscientiousness, characterized by attributes such as competence, deliberation, order, and self-discipline (Costa and McCrae 2008), aligns naturally with the behavioral requirements necessary for evaluating, selecting, and committing to an annuity contract.

Notably, conscientiousness scores were among the highest of the five-factor model traits in this study’s sample (mean score of 3.26; Table 2), consistent with the mean age of the respondents (68 years; Table 5). Prior empirical research confirms that conscientiousness tends to increase with age (Sutin et al. 2020), suggesting that older individuals are not only exposed to greater lifespan uncertainty but also more likely to possess the personality characteristics that support rational late-life income management strategies, such as annuitization.

The mechanisms underlying this relationship are important for understanding client behavior. Individuals high in conscientiousness may apply competence and deliberation when assessing annuity terms, pricing structures, and long-term guarantees.

A preference for financial order, one of the core descriptors of conscientiousness, may further drive these individuals to seek out instruments that convert uncertain financial futures into predictable lifetime income streams.

Moreover, maintaining lifestyle income stability during retirement—balancing conventional wealth with annuitized income—requires substantial self-discipline. This study’s findings suggest that the self-discipline facet of conscientiousness supports behaviors that resist risky or unsustainable consumption patterns, thereby minimizing longevity risk.

Risk-averse behaviors associated with conscientiousness are particularly important given the financial commitment required by annuity purchases. Consistent with previous literature, individuals exhibiting higher conscientiousness display lower financial risk tolerance (Pinjisakikool 2017; Filkuková et al. 2021), which translates into a greater preference for guaranteed retirement income options.

Achievement-striving, another facet of conscientiousness, likely further supports this behavior by promoting advance planning and goal-oriented action (Costa and McCrae 2008). Prior studies have linked conscientiousness to proactive retirement planning behaviors (Hershey and Mowen 2000; Topa et al. 2018), reinforcing the present study’s conclusion that conscientious individuals not only plan more diligently for retirement but are also more likely to implement strategies, such as annuity purchases, that maximize their post-retirement utility.

Thus, the positive association between conscientiousness and annuity ownership highlights a vital psychological driver behind retirement income decisions. For financial planners, recognizing clients’ conscientiousness levels can offer practical guidance in tailoring retirement income strategies that match behavioral predispositions toward security, disciplined planning, and protection against lifespan uncertainty.

Conversely, higher levels of openness, extraversion, and neuroticism were associated with lower likelihoods of owning annuities, highlighting how risk tolerance, future orientation, and emotional stability shape longevity risk management.

The financial and health-related variables largely aligned with economic theory. However, the positive association between home equity and annuity ownership was somewhat unexpected given prior findings suggesting substitution effects. One explanation may be that individuals view home equity not only as a late-life fallback but also as a financial buffer allowing them to lock in secure annuity income earlier.

The sociodemographic patterns reinforce that longevity risk and retirement income strategies vary across age, race, gender, and education, underscoring the need for financial planners to adopt nuanced, client-specific approaches rather than one-size-fits-all retirement income solutions.

While annuities may offer a valuable solution for certain clients seeking longevity protection, they are not universally appropriate. The decision to adopt an annuity must be aligned with an individual’s financial circumstances, product understanding, and personal preferences.

Implications for Practice

These findings suggest that financial planners can enhance client engagement and retirement income strategies by incorporating personality assessment into client discovery and retirement planning conversations.

Clients exhibiting high conscientiousness may be natural candidates for annuity discussions focused on lifetime income security and optimal consumption smoothing. Conversely, clients high in openness, extraversion, or neuroticism may require additional education on the benefits of lifetime income protection and tailored communication strategies to address potential resistance to annuitization.

To identify these traits, advisers can incorporate short, validated personality assessments such as the Midlife Development Inventory (MIDI) scales or brief Big Five questionnaires into their client onboarding or discovery processes. Open-ended questions during client meetings (e.g., “How do you approach long-term planning?” or “How comfortable are you with structured financial goals?”) can also surface personality-related insights that guide retirement income recommendations.

This study’s positive association between conscientiousness and annuity ownership underscores the importance of incorporating personality assessments into retirement planning. Conscientious individuals, characterized by diligence, organization, and foresight traits, are more inclined to engage in proactive financial behaviors, including adopting annuities to guard against the financial uncertainties of a long retirement horizon.

This finding aligns with Cherry and Asebedo’s (2022a, 2022b) earlier research showing that conscientiousness predicts long-term care and life insurance ownership among older Americans. Financial advisers who can assess and identify conscientiousness in clients may better tailor conversations around guaranteed income solutions, aligning with clients’ natural inclinations toward financial security, planning, and responsibility.

Building on this behavioral foundation, broader research on personality and financial behaviors further supports integrating psychological insights into retirement income strategies. Asebedo et al. (2019) found that conscientiousness was positively associated with saving behavior among older adults, suggesting that individuals exhibiting this trait are more likely to accumulate the wealth necessary for annuity purchases.

Furthermore, Asebedo et al. (2022) demonstrated that positive emotional states, reinforced by personality traits like conscientiousness and emotional stability, contribute to greater wealth creation over time. These findings suggest that conscientious individuals build financial assets more effectively and are better positioned emotionally to engage in rational retirement income decisions, including annuitization.

Moreover, integrating annuities into retirement portfolios can address common behavioral biases that lead to underconsumption in retirement. Blanchett and Finke (2024) demonstrate that retirees with annuitized income streams tend to spend more confidently, effectively doubling their retirement expenditures compared to those relying solely on investment portfolios.

This “license-to-spend” effect highlights that annuities not only provide financial security but also improve retirees’ quality of life by reducing anxiety about depleting assets. Similarly, Pfau (2023) emphasizes that annuities create a stable income floor, which allows retirees to invest the remainder of their portfolio more aggressively, enhancing overall financial resilience.

Given the evidence that conscientious individuals are predisposed to orderly and disciplined financial behaviors, financial planners can strengthen retirement outcomes by matching these clients with annuity strategies that reinforce emotional well-being and long-term financial stability.

Financial planners should consider the interaction of personality with other factors such as health status, wealth levels, and pre-existing income sources when crafting individualized retirement strategies.

By aligning financial recommendations with client personality profiles, planners can deliver more human-centered, effective retirement income strategies that enhance financial well-being across longer retirement horizons.

Limitations and Future Research

This study has several limitations. This study assumes actuarially fair pricing in its theoretical framing; however, annuities in the marketplace often include administrative and risk-loading charges that exceed actuarially fair levels.

These higher costs may contribute to the observed reluctance among consumers. Additionally, annuity products are frequently complex and not well understood by many clients, which can reduce their appeal even when they offer potential longevity protection. Future research should explore the role of product transparency, perceived fairness, and comprehension in influencing annuity adoption behavior.

The cross-sectional design of the HRS data precludes definitive conclusions about causality between personality traits and annuity ownership decisions. Future longitudinal studies could offer deeper insights into how personality stability or changes over time influence retirement decision-making.

Experimental or quasi-experimental research designs could also help establish causality by observing how personality-tailored retirement interventions affect annuity adoption behavior. Such methods would strengthen the evidence base beyond the correlational findings presented here.

Measurement limitations also exist, as annuity ownership was self-reported and may be subject to recall bias or misunderstanding of financial product classifications. Additionally, while the five-factor model captures broad personality dimensions, more granular aspects such as financial literacy, numeracy, and trust-specific traits may further illuminate annuity demand behavior.

Future research could explore the interplay between personality, financial literacy interventions, and annuity product innovation. Cross-cultural comparisons would also provide valuable insights given differences in annuity markets, public pensions, and cultural attitudes toward longevity risk across countries.

Citation

Cherry, Preston D., Sarah Asebedo, and Blain Pearson. 2025. “Personality Traits and Annuity Adoption: Unlocking Behavioral Insights of Retirement Income Strategies.” Journal of Financial Planning 38 (8): 58–72.

References

Agnew, J. R., L. R. Anderson, J. R. Gerlach, and L. R. Szykman. 2008. “Who Chooses Annuities? An Experimental Investigation of the Role of Gender, Framing, and Defaults.” American Economic Review 98 (2): 418–422. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.98.2.418

Ando, A., and F. Modigliani. 1963.” The “Life Cycle” Hypothesis of Saving: Aggregate Implications and Tests.” The American Economic Review 53 (1): 55–84.

APA. 2022. “Personality.” www.apa.org/topics/personality.

Arias, E., B. Tejada-Vera, and F. B. Ahmad. 2022. “Provisional Life Expectancy Estimates for 2021 (Report No. 23).” National Center for Health Statistics. https://doi.org/10.15620/cdc:115217.

Arias, E., and J. Xu. 2020. “United States Life Tables, 2019.” National Vital Statistics Reports 70 (19): 1–25. https://doi.org/10.15620/cdc:107021.

Asebedo, S. D., T. H. Quadria, Y. Chen, and E. Montenegro-Montenegro. 2022. “Individual Differences in Personality and Positive Emotion for Wealth Creation.” Personality and Individual Differences 199, 111854. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2022.111854.

Asebedo, S. D., M. J. Wilmarth, M. C. Seay, K. Archuleta, G. L. Brase, and M. MacDonald. 2019. “Personality and Saving Behavior Among Older Adults.” Journal of Consumer Affairs 53 (2): 488–519. https://doi.org/10.1111/joca.12204.

Benartzi, S., A. Previtero, and R. H. Thaler. 2011. “Annuitization Puzzles.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 25 (4): 143–164. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.25.4.143.

Blanchett, D., and M. Finke. 2024. “Guaranteed Income: A License to Spend.” Alliance for Lifetime Income. www.protectedincome.org/news/license-to-spend/.

Brown, J. R. 2007. “Rational and Behavioral Perspectives on the Role of Annuities in Retirement Planning.” In Overcoming the Saving Slump: How to Increase the Effectiveness of Financial Education and Saving Programs. Edited by A. Lusardi. University of Chicago Press: 178–206.

Brown, J. R., M. D. Casey, and O. S. Mitchell. 2008. “Who Values the Social Security Annuity?: New Evidence on the Annuity Puzzle.” National Bureau of Economic Research.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2023. “Life Expectancy in the U.S. Dropped for Second Consecutive Year in 2021.” National Vital Statistics Reports. www.cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/nchs_press_releases/2022/20220831.htm.

Cherry, P. D., and S. Asebedo. 2022a. “Personality Traits and Long-Term Care Financial Risks Among Older Americans.” Personality and Individual Differences 192, 111560. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.111560.

Cherry, P. D., and S. Asebedo. 2022b. “Personality Traits and Life Insurance Ownership Among Older Americans.” Journal of Personal Finance 21 (2): 51–67.

Cherry, P. D. 2024. Wealth in the Key of Life: Finding your Financial Harmony. John Wiley & Sons.

Costa, P. T., and R. R. McCrae. 2008. “The Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R).” The SAGE Handbook of Personality Theory and Assessment: Personality Measurement and Testing 2: 179–198. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781849200479.n9.

Davidoff, T., J. R. Brown, and P. A. Diamond. 2005. “Annuities and Individual Welfare.” American Economic Review 95 (5): 1573–1590. https://doi.org/10.1257/000282805775014281.

Duckworth, A., and D. Weir. 2010. “Personality, Lifetime Earnings, and Retirement Wealth.” Michigan Retirement Research Center Research Paper No. 2010-235. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1710166.

Dushi, I., and A. Webb. 2004. “Household Annuitization Decisions: Simulations and Empirical Analyses.” Journal of Pension Economics and Finance 3 (2): 109–143. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1474747204001696.

Employee Benefit Research Institute (EBRI). 2023. 2023 Retirement Confidence Survey. www.ebri.org/docs/default-source/rcs/2023-rcs/rcs_23-fs-3_prep.pdf.

Federal Reserve Board. 2023. Survey of Consumer Finances. www.federalreserve.gov/econres/scfindex.htm.

Filkuková, P., P. Ayton, K. Rand, and J. Langguth. 2021. “What Should I Trust? Individual Differences in Attitudes to Conflicting Information and Misinformation on COVID-19.” Frontiers in Psychology 12, 588478.

Guillemette, M. A., T. K. Martin, B. F. Cummings, and R. N. James. 2016. “Determinants of the Stated Probability of Purchase for Longevity Insurance.” The Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance—Issues and Practice 41 (1): 4–23. https://doi.org/10.1057/gpp.2015.26.

Hanewald, K., T. Post, and M. Sherris. 2016. “Portfolio Choice in Retirement—What Is the Optimal Home Equity Release Product?” Journal of Risk and Insurance 83 (2): 421–446.

Health and Retirement Study. 2024, May. RAND HRS Longitudinal File 2020 (V2) Public Use Dataset. Produced and distributed by the University of Michigan with funding from the National Institute on Aging (grant numbers NIA U01AG009740 and NIA R01AG073289). Ann Arbor, MI.

Health and Retirement Study. 2024, May. RAND HRS Fat Files for 2016, 2018, and 2020 Public Use Datasets. Produced and distributed by the University of Michigan with funding from the National Institute on Aging (grant numbers NIA U01AG009740 and NIA R01AG073289). Ann Arbor, MI.

Hershey, D. A., and J. C. Mowen. 2000. “Psychological Determinants of Financial Preparedness for Retirement.” The Gerontologist 40 (6): 687–697.

Hershfield, H. E., D. G. Goldstein, W. F. Sharpe, J. Fox, L. Yeykelis, L. L. Carstensen, and J. N. Bailenson. 2011. “Increasing Saving Behavior Through Age-Progressed Renderings of the Future Self.” Journal of Marketing Research 48 (SPL), S23–S37. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkr.48.spl.s23.

Kahneman, D., and A. Tversky. 1979. “Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision Under Risk.” Econometrica 47 (2): 263. https://doi.org/10.2307/1914185.

Lachman, M. E., and S. L. Weaver. 1997. “The Midlife Development Inventory (MIDI) Personality Scales: Scale Construction and Scoring.” Brandeis University: 1–9.

National Center for Health Statistics. 2023. Health, United States, 2022: Annual Report. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. www.cdc.gov/nchs/hus/index.htm.

Pfau, W. D. 2023. “Understanding Why Annuities Work Better than Bonds in a Retirement Income Portfolio.” Alliance for Lifetime Income. www.protectedincome.org/research/understanding-why-annuities-work-better-than-bonds-in-a-retirement-income-portfolio/.

Pinjisakikool, T. 2017. “The Effect of Personality Traits on Households’ Financial Literacy.” Citizenship, Social and Economics Education 16 (1): 39–51.

RAND Corporation. 2020. RAND HRS longitudinal file 2020 (V2). RAND Center for the Study of Aging, with funding from the National Institute on Aging and the Social Security Administration. Santa Monica, CA.

Sutin, A. R., Y. Stephan, and A. Terracciano. 2020. “Psychological Well-being and Risk of Dementia.” International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 35 (9): 988–995. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.5317.

Topa, G., J. A. Moriano, and M. Depolo. 2018. “Retirement Planning and Psychosocial Factors: An International Review.” Frontiers in Psychology 8, 2160. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02160.

Von Neumann, J., and O. Morgenstern. 1947. Theory of Games and Economic Behavior. 2nd ed. Princeton University Press.

Yaari, M. E. 1965. “Uncertain Lifetime, Life Insurance, and the Theory of the Consumer.” The Review of Economic Studies 32 (2): 137. https://doi.org/10.2307/2296058.