Journal of Financial Planning: September 2022

William Reichenstein, Ph.D., CFA, is head of research at the software firms Social Security Solutions Inc. (https://ssanalyzer.com) and Retiree Inc. (https://incomesolver.com). He is professor emeritus at Baylor University and is a frequent contributor to the Journal of Financial Planning and other leading professional journals. His latest book is Income Strategies: How to Create a Tax-Efficient Withdrawal Strategy to Generate Retirement Income.

JOIN THE DISCUSSION: Discuss this article with fellow FPA Members through FPA's Knowledge Circles.

FEEDBACK: If you have any questions or comments on this article, please contact the editor HERE.

SECURE Act 2.0 passed the House and it is expected to pass the Senate, perhaps with some changes, later this year. This Act would raise the age at which required minimum distributions (RMDs) must begin from the current age of 72 to 73 in 2023, to 74 in 2030, and to 75 in 2033.1 By 2033, this would allow retirees to avoid making any tax-deferred account (TDA, like a 401(k)) withdrawals from ages 72 through 74. However, just because these retirees would not have to make TDA withdrawals in these three years does not mean that they should not make any TDA withdrawals in these years. The tax liability of TDA balances does not disappear if the household chooses to make no TDA withdrawals in these years. Furthermore, this tax liability does not disappear at death. Thus, the objective should be to withdraw TDA funds in a manner that would minimize the embedded tax liability.

Under current law, the same idea applies to, say, mid-60s retired households that are not required to withdraw any funds from their TDAs until age 72. Just because they are not required to make any TDA withdrawals until the year they turn 72 does not mean that they should not make any TDA withdrawals before that year. In this column, I present a case study that clearly explains why households should make some TDA withdrawals in their pre-RMD years before they turn 72, even though they are not required to do so. As would be the case if the SECURE Act 2.0 passes, effective tax management requires households to try to minimize the embedded tax liability of TDA balances, where IRMAAs are properly considered to be federal tax increases.

Case Study

This case considers a single individual, but the same lessons apply to married couples. Nancy was born December 10, 1956, and will turn 66 in December 2022. Her full retirement age is 66 years and four months. She has a primary insurance amount (PIA) of $2,200 and life expectancy of 90 years (or plans for a 90-year life expectancy, in case she should live that long). As of the end of 2022, she has $1.5 million in financial assets consisting of $300,000 in a taxable account with a cost basis of $270,000 and $1.2 million in a TDA. She plans to spend $7,900 per month in real terms each month beginning in January 2023, which is when this case begins. The inflation rate is set at 2.5 percent per year, and it will affect spending, tax brackets, Medicare income threshold levels, and Medicare premiums including, when applicable, income related monthly adjustment amounts (IRMAAs). I assume higher federal tax rates will return in 2026, as scheduled in the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. Nancy lives in a tax-free state.

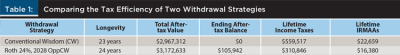

Nancy’s asset allocation is 40 percent stocks–60 percent bonds. Bonds are assumed to earn 3 percent per year, while stocks earn 7.2 percent per year. I set the equity risk premium to be 1 percent below its historic average, due to today’s elevated CAPE ratio. The asset-location decision is to hold stocks in the taxable account and to allocate the TDA balances to attain the 40 percent–60 percent target asset allocation. Her portfolio is rebalanced at the end of each year. Table 1 summarizes the results from two of her withdrawal strategies. In both strategies, she begins Social Security (SS) benefits at age 70. Thus, differences in the strategies’ results are due entirely to differences in the tax efficiencies of their withdrawal strategies.

CW Strategy

In the Conventional Wisdom (CW) Strategy, after satisfying her required minimum distribution (RMD), if any, she withdraws all funds from her taxable account until it is exhausted, then withdraws all funds from her TDA until exhausted, and then withdraws funds from her Roth account (if she has one) until exhausted. Advocates of the CW Strategy believe investors should withdraw all funds from the less-tax-advantaged taxable accounts before withdrawing any funds from the more-tax-advantaged retirement accounts. The CW Strategy is the recommended withdrawal strategy in multiple financial software packages. Since there are no TDA withdrawals in the CW Strategy before Nancy’s RMDs begin in 2028, I believe it is the withdrawal strategy that advocates of the SECURE Act 2.0 would recommend.

As shown in Table 2, in the CW Strategy, from 2023 through 2025, she withdraws all funds to meet her spending from her taxable account and is in the 0 percent tax bracket, meaning her adjusted gross income (AGI) is less than her standard deduction. Withdrawals from taxable accounts are largely tax-free withdrawals of principal, which explains why their AGI is less than their standard deduction in these early retirement years. Her taxable account is exhausted in 2026. She is in the lower end of the 25 percent tax bracket in 2026 and the upper end of the 25 percent bracket in 2027. Her RMDs begin in 2028. In 2028–2045, all withdrawals to meet her spending needs come from her TDA and she is in the 28 percent tax bracket. Her portfolio is exhausted and fails to meet her spending needs in 2046, which is her last year. The longevity of this strategy is 23 years.

In this CW Strategy, beginning in 2029 and continuing for the rest of her life, she pays one IRMAA each month. She pays $22,659 in lifetime IRMAAs.

Roth 24 Percent Strategy

The Roth 24 Percent 2028 Opposite CW Strategy (henceforth, Roth 24 Percent Strategy) is a two-phase withdrawal strategy. In the first phase, which is from 2023 through 2027, she withdraws funds to meet her spending needs following the CW Strategy. Then, she makes Roth conversions, when possible, to fill the 24 percent and lower tax brackets. To be specific, from 2023 through 2025, she withdraws funds from her taxable account, and then makes Roth conversions totaling $491,020. Her taxable account is exhausted late in 2025. In 2026 and 2027, she follows the CW Strategy. Since her taxable account is exhausted, she makes all withdrawals from her TDA, which places her in the 28 percent tax bracket. Thus, she makes no Roth conversions these years because they cannot be made at the 24 percent or lower tax bracket.

In the second phase, which begins in 2028, she uses the Opposite CW Strategy. After withdrawing TDA funds to meet her RMD, she withdraws tax-free funds from her Roth account to meet the rest of her spending needs. In 2028–2043, she is in the lower part of the 15 percent tax bracket. Her Roth account is exhausted in 2044. Her income places her in the lower part of the 25 percent bracket in 2044, near the top of the 25 percent tax bracket in 2045, and near the bottom of the 28 percent bracket in 2046.

From Table 1, this Roth 24 Percent Strategy lasts her 24-year lifetime. Its total after-tax value is $3,172,633, which is the sum of spending, which requires after-tax funds, plus the ending after-tax balance. Her heirs inherit pretax TDA balances of $132,428, but the ending after-tax balance reduces this amount by 20 percent to reflect an estimate of the embedded tax liability.

In this Roth 24 Percent Strategy, in 2025 through 2027, she pays four IRMAAs each month because her 2023 through 2025 Modified Adjusted Gross Income (MAGI) (that is, AGI + tax-exempt interest) levels exceed the fourth MAGI threshold levels in 2025 through 2027. In 2028 and 2029, she pays IRMAAs associated with her MAGI in 2026 and 2027 exceeding the first MAGI threshold level. She pays lifetime IRMAAs totaling $16,380.

The Roth 24 Percent Strategy increases the total after-tax value of Nancy’s financial accounts by $205,361 compared to the CW Strategy. This additional after-tax value is primarily attributed to two factors. First, lifetime income taxes in the Roth 24 Percent Strategy are $248,671 lower than in the CW Strategy. The Roth conversions made in 2023 through 2025 were generally taxed at marginal tax rates (MTRs) of 0 percent, 10 percent, 12 percent, 22 percent, and 24 percent. Since her SS benefits had not yet begun, her MTRs were not 150 percent or 185 percent of her tax bracket due to the taxation of these benefits. Despite having to pay IRMAAs in 2025–2027, which represent spikes in her MTRs, the Roth 24 Percent Strategy is still much more tax efficient than the CW Strategy. The Roth balances provided the ammunition that allowed Nancy to avoid additional TDA withdrawals each year in 2028–2043. Due to the taxation of SS benefits, the first of these additional withdrawals would have been taxed at federal-alone MTRs of 27.75 percent [15 percent bracket × 1.85], with later withdrawals taxed at MTRs of 46.25 percent [25 percent × 1.85]. Another factor contributing to the much lower lifetime income taxes is that Nancy paid taxes on 48.4 percent of lifetime SS benefits in this strategy. In contrast, she paid taxes on 85 percent of her SS benefits in the CW Strategy each year until 2046, when her portfolio was exhausted. The second factor explaining the Roth 12 Percent Strategy’s total after-tax value advantage is that she paid $6,279 less in lifetime Medicare premiums with this strategy.

The tax-free Roth account withdrawals in 2028–2044 did not affect either (1) her provisional income, which is the measure of income used to calculate the taxable amount of SS benefits; nor (2) her MAGI, which is the measure of income that is used to set her Medicare premiums two years hence.2 Thus, despite having to pay substantial IRMAAs in 2025–2027, the large Roth conversions in 2023–2025 allowed her to substantially reduce both her lifetime income taxes and her lifetime Medicare premiums. To read more on how the taxation of SS benefits and IRMAAs cause a retiree’s MTR to rise and fall multiple times as income increases, see Reichenstein (2021, 2019) and Reichenstein and Meyer (2022, 2021a, 2020, and 2018). The lesson is that tax-efficient withdrawal strategies in retirement require taxpayers to navigate this rising and falling pattern of MTRs in retirement as income rises. It is not sufficient to merely look at tax brackets.

Would SECURE Act 2.0 Change the Optimal Withdrawal Strategy?

If the House version of this act becomes law, the Roth 24 Percent Strategy would still be allowed. This act would allow her to avoid RMDs until 2030, when she turns 74. Thus, she would not be required to withdraw any funds from her TDA in 2028 and 2029. However, in the Roth 24 Percent Strategy, she makes TDA withdrawals of $21,484 in 2028 and $22,043 in 2029. Some of these TDA withdrawals are tax free because they are offset by her standard deduction, while the remaining withdrawals are used to fill the 10 percent tax bracket and the lower end of the 15 percent bracket. Lesson: even though the House version of this act would not require Nancy to make any TDA withdrawals in 2028 and 2029, for tax efficiency she should make some TDA withdrawals in these years.

When Would SECURE Act 2.0 Help?

I can think of two situations when the House version of this act would help households add value. In this section, I assume this act is already the law. First, suppose someone either sells a business or a house in retirement and realizes a large taxable capital gain in a year when they turn 72, 73, or 74. If either event causes taxable income to be unusually large in one of those years, the taxpayer could take advantage of the act by not making any TDA withdrawal that year.

Second, consider Janet, who will turn 72 this year. She has a TDA balance of $500,000 from her working career. In addition, her mother died eight calendar years earlier, and Janet inherited a TDA from her mother with a current balance of $1 million. In this case, Janet must withdraw all inherited TDA balances by the end of the year she will turn 74. She could withdraw about one third of the inherited TDA this year and in each of the next two years, which would put her in a high tax bracket. Due to the act, she would not have to withdraw any funds from the $500,000 TDA from her working years at ages 72, 73, or 74, when she is already in a high tax bracket.

Summary

After being fully implemented, the current version of the SECURE Act 2.0 would allow retirees to avoid making any TDA withdrawals in the years they turn age 72 through 74. Advocates of the act consider this a major advantage for retirees. In this article, I explained why it would seldom be optimal for a retired household to avoid making any TDA withdrawals for a three-year period. If a retired household avoids making any TDA withdrawals for multiple years, they will tend to be in a low tax bracket in these years, especially if they have funds in taxable accounts that could be withdrawn to meet their spending needs. A retired household should exploit the opportunity to fill these relatively low-tax-bracket years by making TDA withdrawals or Roth conversions in these pre-RMD years. As shown in a case study, their lower income taxes in the first few retirement years in the CW Strategy, which are also pre-RMD years, will likely be more than offset by much higher income taxes in later retirement years.

For example, in the CW Strategy, which advocates of the SECURE Act 2.0 would favor, households would withdraw all funds to meet their spending needs from taxable accounts until they are exhausted. Until their taxable accounts are exhausted, they will likely be in a relatively low tax bracket in these pre-RMD years. Stated differently, with the CW Strategy, households fail to exploit the low tax brackets in these pre-RMD years. Instead, the much larger TDA balances that remain once RMDs begin will usually result in these households—whether single individual or married couple filing jointly—paying much higher lifetime income taxes and it can result in them paying much higher lifetime Medicare premiums. As demonstrated in the case study, compared to households that fail to make any TDA withdrawals in their pre-RMD years, those households that exploit the relatively low tax brackets in these pre-RMD years could greatly reduce both their lifetime income taxes and their lifetime Medicare premiums.

In the case study, the optimal withdrawal strategy was a multiple-phase strategy. In the first phase, they made Roth conversions in their early retirement years. In the second phase, they made TDA withdrawals to satisfy RMDs and then made tax-free Roth account withdrawals to meet the rest of their spending needs. Financial planners can usually add substantial value to clients’ accounts by helping them combine (1) a smart Social Security claiming strategy, and (2) a tax-efficient multi-phase withdrawal strategy.

To put the lesson from this study in perspective, I and others who service the incomesolver.com software have helped thousands of households identify a tax-efficient withdrawal strategy during their retirement years. I have never seen a case where making no TDA withdrawals (or Roth conversions) in pre-RMD years was the optimal withdrawal strategy. Similarly, just because the SECURE Act 2.0 would not require TDA withdrawals for a few years does not mean that the household should make no TDA withdrawals (or Roth conversions) in these years. Financial planners can demonstrate their planning “alpha” by recommending a strategy that tax-efficiently withdraws TDAs over time, with some of these withdrawals occurring before RMDs start.

Endnotes

- The current required beginning date is April 1 of the year following the year the retiree turns 72. However, if they wait until April of the year that they turn 73 to make their first RMD, then they would have to make two RMDs that year. In this study, I assume they would not want to make two RMDs in this first year because it may cause their income to rise to a higher tax bracket.

- The risk of having to pay much higher lifetime Medicare premiums by households that fail to make any TDA withdrawals in pre-RMD years is especially large for married couples filing jointly (MCFJ). Three calendar years after the death of the first spouse, the survivor will face MAGI threshold levels for singles instead of those for a MCFJ, where these threshold levels for singles are generally half as high as the levels for a MCFJ. See Reichenstein and Meyer (2021b) for additional discussion of this topic.

References

Reichenstein, William. 2021. “Minimizing the Damage of the Tax Torpedo.” Journal of Financial Planning 34 (9): 62–65.

Reichenstein, William. 2019. Income Strategies – How to Create a Tax-Efficient Withdrawal Strategy to Generate Retirement Income. Retiree, Inc.

Reichenstein, William, and William Meyer. 2022. Social Security Strategies. 4th ed. Retiree Income, Inc.

Reichenstein, William, and William Meyer. 2021a. “How Social Security Coordination Can Add Value to a Tax-Efficient Withdrawal Strategy.” Journal of Retirement 9 (2): 37–57.

Reichenstein, William, and William Meyer. 2021b. “Advice for Married Couples When One Spouse Will Die Year(s) Before the Other Spouse.” Journal of Financial Planning 34 (1): 43–45.

Reichenstein, William, and William Meyer. 2020. “Using Roth Conversions to Add Value to Higher-Income Retirees’ Financial Portfolios.” Journal of Financial Planning 33 (2): 46–55.

Reichenstein, William, and William Meyer. 2018. “Understanding the Tax Torpedo and Its Implications for Various Retirees.” Journal of Financial Planning 31 (7): 38–45.