Journal of Financial Planning: January 2021

William Reichenstein, Ph.D., CFA, is head of research at Social Security Solutions, Inc., and Retiree, Inc., and Professor Emeritus at Baylor University. He has published more than 190 articles and written several books, including Social Security Strategies, 3rd Edition (2017) with William Meyer, and Income Strategies (2019).

William Meyer is CEO of Retiree, Inc. in Overland Park, Kansas. He and William Reichenstein developed software to combine a smart Social Security claiming decision with a tax-efficient withdrawal strategy (www.incomesolver.com).

NOTE: Click on Table below for PDF version.

JOIN THE DISCUSSION: Discuss this article with fellow FPA Members through FPA's Knowledge Circles.

In a recent article, we explained how the taxation of Social Security benefits causes many retirees’ marginal tax rate to be 150 percent or 185 percent of their tax bracket.1 We further explained that a $0.01 increase in 2018 income above any of three income-threshold levels can cause a married couple’s 2020 Medicare annual premiums to increase by more than $2,540. Each of these increases in annual premiums represents a spike in marginal tax rates exceeding 254,000 percent.

In this column, we discuss the implications of the taxation of Social Security benefits and income-based Medicare premiums for retired married couples filing jointly, when one spouse dies at least one calendar year before the other spouse. Thus, this column applies to most retired married couples.

Taxation of Social Security Benefits

The taxable portion of Social Security benefits depends on a household’s Provisional Income (PI).2 In formula form, PI = Modified Adjusted Gross Income + (0.5 x Social Security benefits) + tax-exempt interest. Modified Adjusted Gross Income (MAGI) is used in several places in the tax code. However, the definition of MAGI varies with each use. Thus, we use the term MAGIpi to denote this definition of MAGI. For most taxpayers, MAGIpi includes everything in adjusted gross income (AGI), except the taxable portion of Social Security benefits.3

For married couples filing jointly, no Social Security benefits are taxable if their PI is below $32,000. For most married couples, if PI is above $32,000 then their taxable amount of benefits is the lesser of: (1) $0.50 for each dollar of PI between $32,000 and $44,000 plus $0.85 for each dollar above $44,000; or (2) 85 percent of Social Security benefits, which is the maximum taxable amount.

Therefore, when PI is between $32,000 and $44,000, each dollar of additional income generally causes an extra $0.50 of Social Security benefits to be taxed. So, their taxable income rises by $1.50. Thus, their marginal tax rate is 150 percent of their tax bracket, where marginal tax rate denotes the tax rate on the next dollar of income. Each dollar of additional income between $44,000 and PI*, which denotes the PI level where 85 percent of Social Security benefits are taxable, causes an extra $0.85 of Social Security benefits to be taxable. So, their taxable income rises by $1.85. Thus, their marginal tax rate is 185 percent of their tax bracket. At PI*, this couple’s marginal tax rate falls back to their tax bracket.

So, the taxation of Social Security benefits causes a sharp hump (that is, a sharp rise and then a sharp fall) in a taxpayer’s marginal tax rate. This couple’s marginal tax rate rises from 100 percent to 150 percent of their tax bracket at PI of $32,000. It rises to 185 percent of their tax bracket at PI of $44,000, before falling to 100 percent of their tax bracket at PI*. This substantial hump in their marginal tax rate is called the tax torpedo.

The tax bracket at the end of the tax torpedo for singles and married couples is currently 22 percent,4 but according to the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, it is scheduled to increase to 25 percent in 2026. Thus, the federal-alone marginal tax rate at the end of the tax torpedo is scheduled to rise from 40.7 percent, [22 percent x 1.85], to 46.25 percent, [25 percent x 1.85]. Previous research noted5 that this marginal tax rate through 2025 can be as high as 49.95 percent and, beginning in 2026, it can be as high as 55.5 percent.

Income-based Increases in Medicare Part B and D Premiums

The Affordable Care Act instituted higher Medicare premiums—called Income-Related Monthly Adjustment Amounts (IRMAAs)—for retirees as their income level increases. In general, Medicare premiums for one year are based on MAGI levels from two years earlier.

In this column, we use MAGImed to denote the definition of MAGI as used to determine the level of Medicare premiums. MAGImed is defined as AGI plus tax-exempt interest.

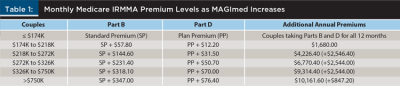

Table 1 shows how monthly 2020 Medicare premium levels increase when MAGImed levels in 2018 breach income threshold levels. The 2020 income threshold levels for MAGImed are $87,000, $109,000, $136,000, $163,000, and $500,000 for single taxpayers, and generally twice these levels for married couples filing jointly.

We discuss how MAGImed affects monthly Medicare premium for a married couple, but the same logic applies to single clients. For MAGImed in 2018 of $174,000 or lower, the standard premium for Part B applies, which in 2020 is $144.60 per month per spouse and, when applicable, the plan premium for Part D (drugs) applies. Part D coverage is optional, but the monthly plan premium varies with each insurance plan.

Consider a married couple filing jointly that is taking Medicare Parts B and D for all 12 months. If their MAGImed exceeds the second, third, or fourth MAGImed income threshold level by $0.01, then their annual Medicare premiums two years hence will increase by more than $2,540. For example, the jump in annual Parts B and D premiums at $218,000 is $2,546.40, [{($144.60 - $57.80) + ($31.50 – $12.20)} x 12 months x 2 partners]. Thus, a couple may have to pay more than $2,540 extra in joint annual Part B and D premiums because their MAGImed rises $0.01 above $218,000, $272,000, or $326,000. These IRMAA premium increases effectively represent spikes in their marginal tax rate that exceed 254,000 percent.6

Taxation of Social Security benefits causes the marginal tax rates of many lower- and middle-income households to be either 150 percent or 185 percent of their tax bracket. Separately, the income-based increases in Medicare premiums (i.e., IRMAAs) can cause spikes in higher-income taxpayers’ marginal tax rates exceeding 254,000 percent.

Implications of Higher Marginal Tax Rates on Retirement Income for Married Couples

What are the implications of high marginal tax rates on retirement income for married couples of all ages when one spouse will die at least one calendar year before the second spouse?

First, one calendar year after the death of the first spouse (assumed male for clarity), the surviving widow will likely be forced into a higher tax bracket. Second, three calendar years after his death, the widow may be forced to pay larger Medicare premiums.

Married couples may greatly reduce the sizes of both their joint lifetime income taxes and their joint lifetime Medicare premiums by using Roth conversions while both partners are alive.7

For example, if the husband dies in 2027, then the surviving widow files taxes in 2028 and subsequent years as a single taxpayer. She’s likely to be in a higher tax bracket for a few reasons. First, she will face tax brackets for single individuals. Second, she will have the lower standard deduction associated with a single taxpayer. Third, if the personal exemption comes back, as scheduled in 2026, she will have only one personal exemption, versus two. Fourth, if she is at least 72, her AGI will probably be only slightly lower than their joint AGI before the husband’s death.

In most cases, the surviving spouse’s AGI will consist primarily of RMDs from tax-deferred accounts (TDAs), like a 401(k), the taxable amount of Social Security benefits, and pension benefits, when applicable.

The surviving widow typically inherits the TDAs of her deceased husband. If the widow is the same age as her husband, her RMDs will be the same size as their combined RMDs would have been. If the widow is slightly younger than her husband then her RMDs will be slightly lower than their combined RMDs would have been, and vice versa.

She’ll also inherit the larger of their two Social Security benefits. Due to the rules determining the taxable amount of Social Security benefits, the taxable amount of Social Security benefits for the widow will likely be close to, and could exceed, the taxable amount if both spouses were alive.

She’ll retain pension benefits based on her earnings record and will usually inherit pension benefits based on her husband’s earnings record. Thus, the widow’s AGI will likely be only slightly lower than their AGI would have been if both spouses were alive. Since her standard deduction will be about half the size of the couple’s standard deduction, her taxable income will probably be only slightly lower than their taxable income would have been if both spouses were alive.

This widow’s Medicare premiums beginning in 2030 will be based on her 2028 filing status as a single taxpayer and her 2028 MAGImed. In addition, her Medicare premiums in 2030 and later years will be based on Medicare income threshold levels for singles, which are generally half the size of Medicare income threshold levels for married couples. For example, suppose a married couple had 2018 MAGImed of $172,000 and they were on Medicare Part B. Based on 2020 premium levels, they would each pay the standard premium of $144.60 for a joint monthly premium of $289.20. Now, suppose the husband died in 2017, which caused the widow’s 2018 MAGImed to decrease to $164,000. Her 2020 monthly Medicare Part B premium would be $462.70, [IRMAA of $318.10 plus $144.60], which far exceeds their joint monthly Medicare premium if both partners were still alive. The survivor’s Medicare premiums may rise sharply three years after the death of the first spouse and remain elevated for the rest of her life.

Implications for Financial Planners

Due to the taxation of Social Security benefits and income-based Medicare premiums, the marginal tax rate of many retirees will be substantially higher than their tax bracket.

Beginning the first calendar year after the death of the first spouse, the surviving widow will likely be in a higher tax bracket each year than the couple’s tax bracket would have been if they filed as a married couple. In addition, beginning three calendar years after the death of the first spouse, the widow may pay sharply higher Medicare premiums than she paid when they filed as a married couple. These couples should consider Roth conversions while both partners are alive to reduce both their joint lifetime income taxes and their joint lifetime Medicare premiums.

Endnotes

- See Reichenstein and Meyer’s “Using Roth Conversions to Add Value to Higher-Income Retirees’ Financial Portfolios,” in the Journal of Financial Planning February 2020 issue.

- Ibid.

- MAGIpi consists of AGI after excluding the taxable portion of Social Security benefits and adding back student loan interest deduction. However, few retirees have student loan interest deductions.

- See endnote No. 1.

- See “Taxable Social Security Benefits and High Marginal Tax Rates,” by Greg Geisler in the Journal of Financial Service Professionals.

- For additional information on Medicare premiums and IRMAAs, see Social Security Administration (2018 and 2019) at www.ssa.gov.

- The time value of money is not a factor when considering a Roth conversion decision this year. Rather, the relevant comparison is the marginal tax rate this year compared to the marginal tax rate when the funds will be withdrawn and spent in retirement. For simplicity, assume there is $1 in a tax-deferred account. Whether converted to a Roth account this year or retained in the TDA, the funds will be withdrawn and spent n-years hence. In either strategy, the funds will be invested in the same asset, which will earn a geometric average annual return of r percent for the n-year investment horizon. If converted to a Roth this year with taxes paid from the converted funds, then the after-tax value this year will be (1 – t0), where t0 is this year’s marginal tax rate. The after-tax value n years hence will be (1 – t0)(1 + r)n. If retained in the TDA for n years, the pretax value n-years hence will be (1 + r)n, while the after-tax value will be (1 – tn)(1 + r)n, where tn is the marginal tax rate n years hence. The Roth conversion provides the larger after-tax value n years hence if t0 < tn. If taxes on the Roth conversion are paid with funds held in a taxable account instead of being paid from funds converted to the Roth IRA then the Roth conversion provides the larger after-tax value n-years hence if t0 £ tn. For additional discussion, see chapter 3 in Income Strategies (2019) by William Reichenstein.