Journal of Financial Planning: September 2022

Executive Summary

- Personal financial salience (PFS) was recently introduced as a concept that describes “how individuals allocate attentional, perceptual, and cognitive resources to their personal financial situation” (Pearson 2021, 87). The study that introduced PFS utilized app- and web-based financial planning product (A&WFPP) usage to proxy PFS, and then used the PFS variable to show that individuals who frequently use these products are more likely to find it easier to cover their bills, have an emergency fund, have a plan for their children’s college education, and have a plan for retirement.

- Using similar methodology, this follow-up study examines the effect of PFS on financial satisfaction and retirement insecurity. Financial satisfaction is defined as satisfaction with one’s financial condition, and retirement insecurity is defined as an individual’s fear of running out of money during retirement.

- While prior research showed that higher levels of PFS are associated with objective measures of financial health, this study shows that higher levels of PFS are associated positively with non-objective measures of financial health. The empirical results reveal that, when compared to individuals with low PFS levels, those with high PFS levels are more likely to have higher levels of financial satisfaction. Furthermore, those with high PFS levels are more likely to have low retirement insecurity.

Blain Pearson, Ph.D., CFP®, AFC, is an assistant professor of finance at Coastal Carolina University. Blain earned his B.B.A. and M.B.A. from Campbell University, his Ph.D. from Texas Tech University, is a CERTIFIED FINANCIAL PLANNER™, is an accredited financial counselor, and has multiple years of practitioner experience.

Editor’s note: This is a follow-up research paper. The original paper, “The Role of Personal Financial Salience” can be found in the August 2021 issue of the Journal of Financial Planning.

JOIN THE DISCUSSION: Discuss this article with fellow FPA Members through FPA's Knowledge Circles.

FEEDBACK: If you have any questions or comments on this article, please contact the editor HERE.

NOTE: Click on images below for PDF versions

Introduction and Research Question

Personal financial salience (PFS) can assist individuals with their objective personal financial health. Pearson (2021) showed that higher levels of PFS resulted in individuals finding it easier to cover their bills, have an emergency fund, have a plan for their children’s college education, and have a plan for retirement. However, financial health goes beyond objective measures of assessment.

The goal of this follow-up study is to examine the role of PFS on non-objective measures of financial health. Specifically, this study examines the influence of PFS on financial satisfaction and retirement insecurity, where retirement insecurity is defined as an individual’s fear of running out of money during retirement. If personal financial goals, and the plan to achieve those goals, are salient, individuals are better positioned to assess whether they are on track to achieve those goals. This study posits that PFS allows individuals to have an improved understanding of the direction of their financial future, resulting in financial satisfaction increases and the reduction of retirement insecurity.

Financial Satisfaction

For many families, household financial management has been well-documented as one of life’s major stressors (Zagorsky 2003; Hakkio and Keeton 2009; Pearson, Korankye, and Salehi 2021). With an ever-changing tax code, recent increases in retirement preparation responsibility, healthcare planning, and the plethora of other aspects that personal financial management encompasses, managing financial stress and anxiety may be a crucial element in promoting financial satisfaction.

Zimmerman (1995) spearheaded financial satisfaction research, which aptly characterized financial satisfaction as a state of freedom from financial worries. This study’s definition of financial satisfaction mirrors the definition offered by Joo and Grable (2004), where financial satisfaction is defined as satisfaction with one’s financial situation. Understanding the factors to promote financial satisfaction is crucial, as financial satisfaction is closely correlated with life satisfaction (Vera-Toscano, Ateca-Amestoy, and Serrano-Del-Rosal 2006; Xiao, Tang, and Shim 2009), marital satisfaction (Archuleta, Britt, Tonn, and Grable 2011), and other measures of subjective well-being (Ngamaba, Armitage, Panagioti, and Hodkinson 2020).

Retirement Insecurity

As life expectancies continue to rise, planning for a longer retirement is a paramount consideration to ensure a satisfactory retirement experience. Individuals can now expect to spend at least one-fourth of their lives in retirement (Kim and Moen 2001). The increasing number of years spent during retirement likely parallel increases in retirement insecurity.

Retirement insecurity is defined in this study as anxiety or uncertainty regarding the retirement experience. Research has connected retirement insecurity to retirement income concerns (Hershey, Henkens, and van Dalen 2010), healthcare affordability (Lucifora and Vigani 2018), existing debt levels (Lusardi, Mitchell, and Oggero 2020), and longevity (Battistin, Brugiavini, Rettore, and Weber 2009). Many of the factors connected to retirement insecurity are frequently assessed when working with financial planning professionals.

Personal Financial Salience (PFS)

The load theory of attention dictates that individuals have limited attentional and cognitive resources that can be deployed to process task-relevant stimuli (Lavie and Tsla 1994; Forster and Lavie 2009). The perceived amount of attentional and cognitive resources required to process task-relevant stimuli has been defined as one’s perceptual load (Lavie and Tsla 1994; Lavie 1995; Murphy and Greene 2016). In other words, perceptual load is “. . . the amount of information involved in the processing of task stimuli” (Macdonald and Lavie 2011, 1780).

High perceptual load tasks require higher degrees of attentional and cognitive resources (Forster and Lavie 2009). Given that individuals have limited attentional and cognitive resources (Forster and Lavie 2009; Franconeri, Alvarez, and Cavanagh 2013), task-relevant stimuli that require higher attentional and cognitive resources leads to the depletion of these resources (Lavie 2005). Likewise, as the complexity of the task increases, resource depletion occurs quicker (Forster and Lavie 2009; Lavie, Ro, and Russell 2003). When attentional and cognitive resources are strained in high perceptual load tasks, performance inefficiencies result (Eysenck, Derakshan, Santos, and Calvo 2007).

Researchers have suggested that when engaged in a high perceptual load task, individuals will allocate attentional and cognitive resources to the most salient task-relevant stimulus (Eltiti, Wallace, and Fox 2005; Benoni and Tsla 2013). A salient stimulus is a stimulus that is cognitively prominent (Gaspelin and Luck 2018). Stated differently, a salient stimulus enters one’s thoughts more often than non-salient stimuli. Thus, saliency can be defined as the condition of being especially perceptible or prominent. Increases in saliency have been shown to be associated with planned action and a higher likelihood of goal achievement (Parr and Friston 2019).

Personal financial salience (PFS) was recently introduced as a concept that describes “how individuals allocate attentional, perceptual, and cognitive resources to their personal financial situation” (Pearson 2021, 87). The study that introduced PFS utilized app- and web-based financial planning product (A&WFPP) usage to proxy PFS, and then used the PFS variable to show that individuals who frequently use these products are more likely to find it easier to cover their bills, have an emergency fund, have a plan for their children’s college education, and have a plan for retirement.

This study examines the effect of PFS on financial satisfaction and retirement insecurity. Financial satisfaction is defined as satisfaction with one’s financial condition, and retirement insecurity is defined as an individual’s fear of running out of money during retirement. While not directly related to financial satisfaction or retirement insecurity, research has shown that increases in the engagement of financial planning is closely connected to the reduction of financial anxiety (Grable, Heo, and Rabbani 2015). Correspondingly, higher degrees of PFS increases the attentional resource deployment to one’s financial situation (Pearson 2021). This study hypothesizes that increases in PFS prompt individuals to allocate more attentional and cognitive resources to their financial condition, leading to an improved understanding of one’s financial situation and the development of planned actions. An improved understanding of one’s financial condition provides insight and financial reassurance, which is theorized to increase financial satisfaction and reduce retirement insecurity.

Methods

Data from the National Financial Capability Study (NFCS) are utilized. The NFCS is a project of the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA) Investor Education Foundation. The questions from which the variables are constructed can be located on the FINRA Foundation’s website:

www.usfinancialcapability.org/downloads.php.

The hypothesis is examined by estimating ordered probit regression models for financial satisfaction and retirement insecurity. The financial satisfaction dependent variable comes from the NFCS question, “Overall, thinking of your assets, debts, and savings, how satisfied are you with your current personal financial condition?” The responses available to participants include: 1 (Not at All Satisfied); 2; 3; 4; 5; 6; 7; 8; 9; and 10 (Extremely Satisfied). The original data are recoded to the value of “1” if the retiree responded with 1 (Not at All Satisfied), 2, or 3; the value “2” if the retiree responded with 4, 5, 6, or 7; and the value “3” if the retiree responded with 8, 9, or 10.

The retirement insecurity dependent variable comes from the question, “How strongly do you agree or disagree with the following statements? I worry about running out of money in retirement.” The responses available to participants include: 1 (Strongly Disagree); 2; 3; 4 (Neither Agree nor Disagree); 5; 6; and 7 (Strongly Agree). The original data are recorded to the value “1” if the retiree responded with 1 (Strongly Disagree) or 2; the value “2” if the retiree responded with 3, 4 (Neither Agree nor Disagree), or 5; and the value “3” if the retiree responded with 6 or 7 (Strongly Agree).

The explanatory variable of interest comes from the question, “How often do you use websites or apps to help with financial tasks such as budgeting, saving, or credit management (e.g., GoodBudget, Mint, Credit Karma, etc.)? Please do not include websites or apps for making payments or money transfers.” The responses available to participants include: 1 (Never), 2 (Sometimes), or 3 (Frequently). For a robust discussion on the validation of this variable as a proxy for PFS, see Pearson (2021).

For control measures, indicator variables for whether the respondent is white, married, male, owns their home, has an emergency fund, has a four-year college degree, has at least one child, and categorical measures for age and income are considered. Prior research has shown that race (Dettling et al. 2017; Pearson 2020), marital status (Garbinsky and Gladstone 2019), males (Cueva and Rustichini 2015), homeownership (Joo 2008; Pearson and Kalenkoski 2022; Pearson and Lacombe 2021), having an emergency fund (Xiao, Chen, and Chen 2014), education (Fan and Chatterjee 2019), children (Plagnol 2011), age (Bleijenberg et al. 2017), and income (Pearson and Guillemette 2020; Thornton and Tommaso 2020) are associated with the dependent variables examined in this study. Consequently, these variables are added to both models for control purposes. Survey weights are used.

Results

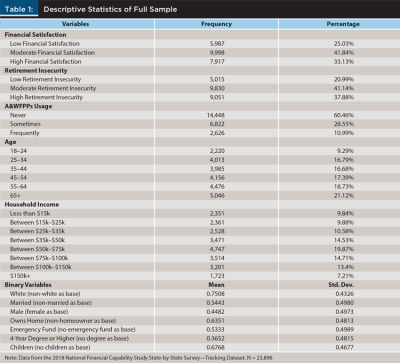

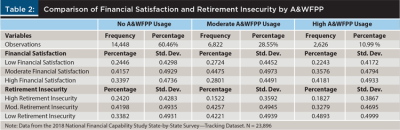

Table 1 provides the descriptive statistics of the sample. Table 2 provides a comparison of low, moderate, and high levels of PFS, measured as app- and web-based financial planning product usage, on the varying levels of financial satisfaction and retirement insecurity. Those with the highest level of app- and web-based financial planning product usage had the highest frequency of high financial satisfaction. For retirement insecurity, 48.93 percent of those with high product usage have low retirement insecurity. As a comparison, only 33.82 percent of those with no product usage have low retirement insecurity. Those with no product usage also have the highest frequency of high retirement insecurity.

Tables 3 and 4 provide the average marginal effects from the financial satisfaction and retirement insecurity ordered probit regressions, respectively. The findings reveal that higher levels of PFS are associated positively with higher levels of financial satisfaction and associated negatively with lower levels of financial satisfaction. Additionally, the findings reveal that higher levels of PFS are associated positively with lower levels of retirement insecurity and associated negatively with higher levels of retirement insecurity. The results are statistically and economically significant.

Limitations

As with the Pearson (2021) PFS study, a limitation of the current study is the lack of a direct measure of PFS. A deeper understanding of the connection between PFS and app- and web-based financial planning product usage would help validate the usage of these products as an appropriate method to measure PFS.

Discussion

This study examines the relationship between personal financial salience (PFS) and two non-objective measures of financial health: financial satisfaction and retirement insecurity. The empirical results suggests that increases in PFS, as measured by frequent use of app- and web-based financial planning products, is associated positively with higher levels of financial satisfaction and lower levels of retirement insecurity. Like the objective measures from the Pearson (2021) study, increases in PFS is closely correlated to financial health improvements.

Financial planning professionals should use the findings of this study carefully. While actively increasing PFS is shown to increase financial satisfaction and reduce retirement insecurity, motivational relevance and informational load are important considerations. Financial advice is a tailor-made process. Thus, efforts to increase saliency should be targeted and specific to the unique needs of clients. Without this consideration, the perceptual load of clients is unfruitfully increased, resulting in clients deploying unneeded attentional and cognitive resources. As Grable and Britt (2012) note, counterproductive stress is a consideration for financial planning professionals.

PFS designed to match relevant client situations can create effective and efficient uses of client time. Consequently, financial planning professionals can add value to clients by filtering, and then prompting, relevant information and action items to make salient for clients. By considering client relevance, clients are better positioned to focus on productive tasks in a manner that is conducive to their limited attentional and cognitive resources.

Perhaps one of the best uses of the findings is the role of PFS in underscoring client progress and goal accomplishment. Goal achievement guides behaviors to productive epilogues and are cognitive representations of financial progress. Financial planning professionals who highlight the progress of their clients create positive PFS, which can aid in promoting financial satisfaction and lowering retirement insecurity.

Conclusions

This study examined the role of personal financial salience (PFS) and its association with financial satisfaction and retirement insecurity. The usage of app- and web-based financial planning products served as a proxy for PFS.

The empirical results reveal that, when compared to individuals with low PFS levels, those with high PFS levels are more likely to have higher levels of financial satisfaction. Furthermore, those with high PFS levels are more likely to have low retirement insecurity.

Citation

Pearson, Blain M. 2022. “The Role of Personal Financial Salience: Part II.” Journal of Financial Planning 35 (9): 60–69.

References

Archuleta, Kristy L., Sonya L. Britt, Teresa J. Tonn, and John E. Grable. 2011. “Financial Satisfaction and Financial Stressors in Marital Satisfaction.” Psychological reports 108 (2): 563–576.

Battistin, Erich, Agar Brugiavini, Enrico Rettore, and Guglielmo Weber. 2009. “The Retirement Consumption Puzzle: Evidence from a Regression Discontinuity Approach.” American Economic Review 99 (5): 2209–26.

Benoni, Hanna, and Yehoshua Tsal. 2013. “Conceptual and Methodological Concerns in the Theory of Perceptual Load.” Frontiers in Psychology 4: 522.

Bleijenberg, Nienke, Alexander K. Smith, Sei J. Lee, Irena Stijacic Cenzer, John W. Boscardin, and Kenneth E. Covinsky. 2017. “Difficulty Managing Medications and Finances in Older Adults: A 10-Year Cohort Study.” Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 65 (7): 1455–1461.

Cueva, Carlos, and Aldo Rustichini. 2015. “Is Financial Instability Male-Driven? Gender and Cognitive Skills in Experimental Asset Markets.” Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 119: 330–344.

Dettling, Lisa J., Joanne W. Hsu, Lindsay Jacobs, Kevin B. Moore, and Jeffrey Thompson. 2017. Recent Trends in Wealth-Holding by Race and Ethnicity: Evidence from the Survey of Consumer Finances. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US).

Eltiti, Stacy, Denise Wallace, and Elaine Fox. 2005. “Selective Target Processing: Perceptual Load or Distractor Salience?” Perception & Psychophysics 67 (5): 876–885.

Eysenck, Michael W., Nazanin Derakshan, Rita Santos, and Manuel G. Calvo. 2007. “Anxiety and Cognitive Performance: Attentional Control Theory.” Emotion 7 (2): 336–353.

Fan, Lu, and Swarn Chatterjee. 2019. “Financial Socialization, Financial Education, and Student Loan Debt.” Journal of Family and Economic Issues 40 (1): 74–85.

Franconeri, Steven L., George A. Alvarez, and Patrick Cavanagh. 2013. “Flexible Cognitive Resources: Competitive Content Maps for Attention and Memory.” Trends in Cognitive Sciences 17 (3): 134–141.

Forster, S., and N. Lavie. 2009. “Harnessing the Wandering Mind: The Role of Perceptual Load.” Cognition 111 (3): 345–355.

Garbinsky, Emily N., and Joe J. Gladstone. 2019. “The Consumption Consequences of Couples Pooling Finances.” Journal of Consumer Psychology 29 (3): 353–369.

Gaspelin, Nicholas, and Steven J. Luck. 2018. “The Role of Inhibition in Avoiding Distraction by Salient Stimuli.” Trends in Cognitive Sciences 22 (1): 79–92.

Grable, John E., and Sonya L. Britt. 2012. “Assessing Client Stress and Why It Matters to Financial Advisors.” Journal of Financial Service Professionals 66 (2).

Grable, John, Wookjae Heo, and Abed Rabbani. 2015. “Financial Anxiety, Physiological Arousal, and Planning Intention.” Journal of Financial Therapy 5 (2).

Hakkio, Craig S., and William R. Keeton. 2009. “Financial Stress: What Is It, How Can It Be Measured, and Why Does It Matter.” Economic Review 94 (2): 5–50.

Hershey, Douglas A., Kène Henkens, and Hendrik P. van Dalen. 2010. “What Drives Retirement Income Worries in Europe? A Multilevel Analysis.” European Journal of Ageing 7 (4): 301–311.

Joo, Sohyun. 2008. “Personal Financial Wellness.” In Handbook of Consumer Finance Research. Springer, New York, NY: 21–33.

Joo, So-hyun, and John E. Grable. 2004. “An Exploratory Framework of the Determinants of Financial Satisfaction.” Journal of Family and Economic Issues 25 (1): 25–50.

Kim, Jungmeen E., and Phyllis Moen. 2001. “Moving into Retirement: Preparation and Transitions in Late Midlife.” Handbook of Midlife Development: 487–527.

Lavie, Nilli. 1995. “Perceptual Load as a Necessary Condition for Selective Attention.” Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance 21 (3): 451.

Lavie, Nilli. 2005. “Distracted and Confused?: Selective Attention under Load.” Trends in Cognitive Sciences 9 (2): 75–82.

Lavie, N., T. Ro, and C. Russell. 2003. “The Role of Perceptual Load in Processing Distractor Faces.” Psychological Science 14 (5): 510–515.

Lavie, Nilli, and Yehoshua Tsal. 1994. “Perceptual Load as a Major Determinant of the Locus of Selection in Visual Attention.” Perception & Psychophysics 56 (2): 183–197.

Lucifora, Claudio, and Daria Vigani. 2018. “Healthcare Utilization at Retirement: The Role of the Opportunity Cost of Time.” Health Economics 27 (12): 2030–2050.

Lusardi, Annamaria, Olivia S. Mitchell, and Noemi Oggero. 2020. “Debt and Financial Vulnerability on the Verge of Retirement.” Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 52 (5): 1005-1034.

Macdonald, James SP, and Nilli Lavie. 2011. “Visual Perceptual Load Induces Inattentional Deafness.” Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics 73 (6): 1780–1789.

Murphy, Gillian, and Ciara M. Greene. 2016. “Perceptual Load Affects Eyewitness Accuracy and Susceptibility to Leading Questions.” Frontiers in Psychology 7: 1322.

Ngamaba, Kayonda Hubert, Christopher Armitage, Maria Panagioti, and Alexander Hodkinson. 2020. “How Closely Related Are Financial Satisfaction and Subjective Well-Being? Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics 85: 101522.

Parr, Thomas, and Karl J. Friston. 2019. “Attention or Salience?” Current Opinion in Psychology 29: 1–5.

Pearson, Blain. 2020. “Demographic Variations in the Perception of the Investment Services Offered by Financial Advisors.” Journal of Accounting and Finance 20 (3): 127–139.

Pearson, Blain. 2021. “The Role of Personal Financial Salience.” Journal of Financial Planning 34 (8): 74–86.

Pearson, Blain, and Charlene M. Kalenkoski. 2022. “The Association between Retiree Migration and Retirement Satisfaction.” Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning 33 (1): 56–65.

Pearson, Blain, and Donald Lacombe. 2021. “The Relationship between Home Equity and Retirement Satisfaction.” Journal of Personal Finance 20 (1): 40–50.

Pearson, Blain, and Michael Guillemette. 2020. “The Association Between Financial Risk and Retirement Satisfaction.” Financial Services Review 28 (4): 341–350.

Pearson, Blain, Thomas Korankye, and Hossein Salehi. 2021. “Comparative Advantage in the Household: Should One Person Specialize in a Household’s Financial Matters?” Journal of Family and Economic Issues: 1–11.

Plagnol, Anke C. 2011. “Financial Satisfaction over the Life Course: The Influence of Assets and Liabilities.” Journal of Economic Psychology 32 (1): 45–64.

Thornton, John, and Caterina Di Tommaso. 2020. “The Long-Run Relationship between Finance and Income Inequality: Evidence from Panel Data.” Finance Research Letters 32: 101180.

Vera-Toscano, Esperanza, Victoria Ateca-Amestoy, and Rafael Serrano-Del-Rosal. 2006. “Building Financial Satisfaction.” Social Indicators Research 77 (2): 211–243.

Xiao, Jing Jian, Cheng Chen, and Fuzhong Chen. 2014. “Consumer Financial Capability and Financial Satisfaction.” Social Indicators Research 118 (1): 415–432.

Xiao, Jing Jian, Chuanyi Tang, and Soyeon Shim. 2009. “Acting for Happiness: Financial Behavior and Life Satisfaction of College Students.” Social Indicators Research 92 (1): 53–68.

Zagorsky, Jay L. 2003. “Husbands’ and Wives’ View of the Family Finances.” The Journal of Socio-Economics 32 (2): 127–146.

Zimmerman, Shirley. 1995. Understanding Family Policy: Theories and Applications. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.