Journal of Financial Planning: April 2024

NOTE: Please be aware that the audio version, created with Amazon Polly, may contain mispronunciations.

Executive Summary

- This research uses the theory of polymedia (Madianou and Miller 2012) to study perspectives on productivity and confidence in virtual financial planning meetings.

- Results suggest that planners are more likely than clients to think virtual meetings will be productive.

- Client results show a significant, positive relationship between their confidence in troubleshooting virtual environments and their view that these meetings can be as productive as in-person meetings.

- Planner results show a positive relationship between their confidence in navigating virtual environments and their view that these meetings can be as productive as in-person meetings.

- Planners should be proficient in troubleshooting technical issues to increase client confidence and be intentional about determining which clients require in-person meetings.

Nathan Collier, CFP®, AIF, is a wealth adviser at Pinkerton Retirement Specialists, specializing in private and corporate wealth management, and a Ph.D. student in the personal financial planning program at Kansas State University.

Jason N. Anderson, CFP®, CPA, is a multi-term lecturer and director of the personal finance program at the University of Kansas and a Ph.D. student studying personal financial planning at Kansas State University.

Darin Carroll, CFP®, BFA, AAMS, is a financial adviser who splits his time between Colorado Springs, Colorado, and south Florida. After decades in the investment industry, he remains passionate about the life-changing impact a trusted, values-focused adviser and a well-executed financial plan can have on client families.

Megan McCoy, Ph.D., LMFT, AFC, CFT-I, is an assistant professor of personal financial planning at Kansas State University. She serves on the board of directors for the Financial Therapy Association. She is also the co-editor of Financial Planning Review.

JOIN IN THE DISCUSSION: Discuss this article with fellow FPA Members through FPA's Knowledge Circles.

FEEDBACK: If you have any questions or comments on this article, please contact the editor HERE.

NOTE: Click on the images below for PDF versions.

In 2020, much of the workforce had significantly altered their schedules, commutes, and daily routines (Bai et al. 2021). It is estimated that as much as 50 percent of the U.S. workforce began working from home during the COVID-19 pandemic (Brynjolfsson et al. 2020). Technology-driven communication has become the norm for many. In addition, despite being discouraged from leaving the confines of home, many Americans relocated during this time due to the rise of remote work that allowed people to escape the cost, health, and safety concerns of densely populated areas. In 2020, 31.96 million Americans moved (Frost 2021). With so much of daily life altered, virtual communication became the new normal for many financial planners.

Currently, most, if not all, of the COVID-19 mandates are no longer impacting face-to-face meetings. However, virtual interaction is a mainstay form of communication in professional and personal relationships (Chan et al. 2022). There have been little to no empirical studies completed to provide planners with understanding and evidence-based best practices. What are financial planners’ and their clients’ experiences in virtual meetings? Are planners and clients experiencing the same advantages and disadvantages to online versus in-person meetings? Moreover, are planners potentially making uninformed assumptions about their clients’ experiences in virtual meetings?

To provide insights into these research questions, this paper compared the perspectives of financial planners and their clients on the productivity of virtual versus in-person meetings. The paper also explores how technology self-efficacy (i.e., confidence in using technology) influences these perspectives of meeting productivity (Bandura 1977), as technology self-efficacy has been found to be a key factor in the assessment of virtual communication (Pellas 2014). Additionally, the paper briefly presents client responses to an open-ended question regarding their preferences for virtual or in-person meetings.

Theory

The theory of polymedia (Madianou and Miller 2012) centers on the idea that effective utilization of technology necessitates specific prerequisites, including access, availability, affordability, and digital literacy. By recognizing these preconditions, practitioners are encouraged to consider that clients have the necessary means and skills to engage with various technological platforms. In our study, we examine how access and literacy are directly related to one’s technology self-efficacy. Self-efficacy was originally defined by Bandura (1977) as a domain-specific belief in one’s capabilities to produce the desired results of a task. Technology self-efficacy can be seen as an individual’s belief in their ability to use and adapt to technology effectively. It influences motivation, skill acquisition, adaptability, and problem-solving related to technology, which should influence how financial planners and clients assess the value of technology in their work (Holden and Rada 2011).

The theory of polymedia (Madianou and Miller 2012) also emphasizes the social and emotional consequences of choosing different media. That technology affects relationships. It prompts practitioners to reflect on the moral responsibility of utilizing diverse media types and consider how these choices impact the financial planner–client relationship. By considering the socioemotional aspects, such as building trust, rapport, and empathy, practitioners can intentionally leverage communication technologies to enhance the overall client experience. This theory encourages a thoughtful approach to media usage, ensuring that professionals prioritize both the financial goals of their clients and the quality of the professional-client relationship (Archuleta et al. 2021).

Literature Review

Learning from Other Disciplines About Tele-Health

Virtual financial planning is a relatively new concept with little research. Instead, financial planners have had to rely on findings from similar client-focused professions such as tele-mental health and tele-medicine. For example, Sensenig et al. (2020) did a systematic review of tele-mental health research. Their findings suggest that virtual client meetings increased geographical reach, decreased costs, and reduced dropout percentage among clients. If these characteristics translate to financial planning, virtual planning could be a powerful tool worthy of continued use. However, their results also highlighted challenges when working with clients online due to technological issues and frustrations.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, tele-medicine became critical for treating patients outside of personal interaction (Calton, Abedini, and Fratkin 2020). Like financial planning, those seeking medical attention can now seek care in a virtual setting. Financial planning and healthcare share many characteristics, including risk management under uncertainty, diagnoses and prognoses of various complications, and the transfer of recommendations from expert to patient or client (Parnaby 2011). Tele-medicine has been accepted and utilized in nursing, radiology, neurology, and other areas (Nittari et al. 2020). Over 15 percent of physicians work in offices that utilize tele-medicine within their practice (Dorsey and Topol 2020). Technology can be utilized 24/7 and gives medical professionals an efficient tool to diagnose and screen across providers (Hollander and Carr 2020). From a patient’s perspective, tele-medicine is viewed as more efficient, but some patients may have issues with connectivity and a concern that the doctor will not be able to fully examine the area of need (Ahmad et al. 2021). While virtual visits were accepted during the pandemic, 70 percent of patients still preferred in-person treatments (Ahmad et al. 2021). However, Boehm et al. (2020) found that patients with greater health risks relating to COVID-19 preferred virtual treatment as a way of limiting exposure.

Technology Self-Efficacy

Self-efficacy is the belief in one’s ability to organize and execute the courses of action required to attain intended results (Bandura et al. 1977). Technology self-efficacy encompasses an individual’s beliefs, attitudes, and perceptions regarding their ability to interact with and utilize various forms of technology effectively. It can be analogized to one’s sense of confidence (Rahman, Ko, Warren, and Carpenter 2016). However, this form of self-efficacy impacts behavior more than it does confidence, as it directly influences the individual’s desire to approach, learn, and master technological tools and software (Ahmad and Safaria 2013). Technology self-efficacy influences their perception of being able to possess the skills and knowledge required to operate technology successfully. Technology self-efficacy has a direct impact on one’s adaptability (as programs evolve and update) and capacity to troubleshoot and resolve technological issues. All these aspects of technology self-efficacy will influence the planner’s and the client’s evaluation of whether technology is a valuable tool for their work together (Holden and Rada 2011).

Technology self-efficacy has not been examined in financial planning to the same extent as the field of education. Virtual learning in the classroom is a good litmus test of virtual planning. The goal of both endeavors is to successfully transfer information. Research by Pellas (2014) found technology self-efficacy to be positively related to students’ cognitive and emotional engagement with the class. Wang and Hamid (2022) found that self-efficacy was also associated with improved final grades in online classes. This finding—if translated to financial planning practices—may mean that clients with higher technology self-efficacy are more likely to comprehend and retain information in virtual meetings. However, Jan (2015) found that technology self-efficacy did not significantly predict online education satisfaction.

A study such as this one necessitates an examination of the role of technology self-efficacy in the financial planner. In terms of prior research, we can analogize teachers to planners. Technology self-efficacy is an important motivational factor for teachers (Lemon and Garvis 2015). BiriŞÇi and Kul (2019) found a significant positive correlation between teachers receiving education on technology use and their self-efficacy in effectively using technology. However, Corry and Stella (2018) concluded that the link between self-efficacy and student success has yet to be proven in virtual interaction at the same level as in-person classrooms.

Technology Acceptance

Research in other fields has also examined some common demographic factors related to technology acceptance, which may significantly impact technology acceptance for older patients. In particular, older women may be less likely to accept new technologies as they are shown to have more challenges accepting new technology (Arning and Ziefle 2009). Race may significantly impact technology, as Black and Hispanic respondents may be less likely to use the technology than White adults (Mitchell, Chebli, Ruggiero, and Muramatsu 2018). Race and technology acceptance may also contribute to the wealth gap in the United States, as minorities have been shown to engage in fewer technology-based purchases (Wejnert 2002). Income level has shown a moderating relationship between intent and usage of technology, as those with higher income levels seem to value the increased convenience of technology-based transaction methods (See-To, Papagiannidis, and Westland 2014). Kari (2020) concluded that marital status plays a significant moderating role in virtual resources, and marital status may have a significant impact on the technology acceptance of women (Nadler and Kufahl 2014). Finally, education attainment level has been found to have a significant positive relationship with overall computer use in the workforce (Riddell and Song 2017).

Methods

Data and Sample

The data used for this survey is from the Developing and Maintaining Client Trust and Commitment in a Rapidly Changing Environment Study (2021) provided by the Financial Planning Association (FPA), the Kansas State University Personal Financial Planning Program, MQ Research & Education, and Allianz Life Insurance Company of North America (Allianz Life), but none of these entities has reviewed or approved of this use. Data collection was completed in two phases, each consisting of multiple steps, to gather information from a convenience sample of financial planners and their clients. In the first phase, FPA provided its members’ email addresses to the Money Quotient Research Consortium (MQRC). The MQRC team sent emails containing a direct link to the survey for financial planners to FPA members requesting their participation. MQRC, FPA, Michael Kitces, XY Planning Network, and the Financial Therapy Association posted the direct link to the survey for financial planners on their respective social media platforms. In total, n = 395 planner surveys were collected.

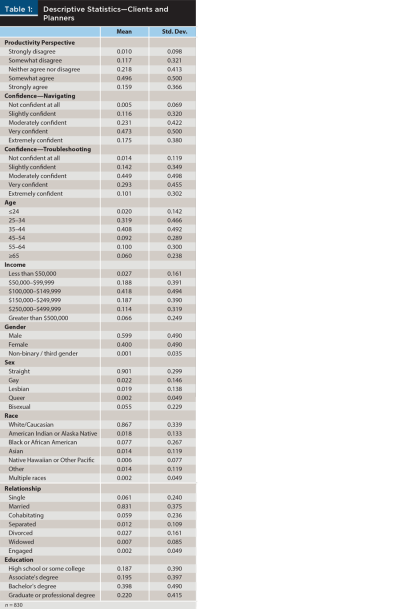

The second phase focused on reaching financial planning clients. The MQRC team asked each participating financial planner to invite at least five clients to participate in the research. Planners provided clients with a random number-generated hyperlink to the Qualtrics survey specific for financial planning clients. The random number-generated hyperlink allowed the data collection team to match the planners’ surveys to their clients’ surveys while maintaining anonymity. As an incentive, the first 340 clients who completed the survey were provided a choice of receiving a $50 Amazon gift card or having the gift card donated to a charity of their choosing. This process collected a total of n = 435 client surveys. Both phases and all data collection steps were completed during the first quarter of 2021. For this study, missing values across the planner and client surveys were addressed through mean substitution in Stata. Demographic information is presented in Table 1.

Empirical Model

Productivity of Virtual Meetings

The first level of analysis for this study focused on the differences in perspectives regarding the productivity of virtual meetings between clients and financial planners. Both groups were asked to rate their level of agreement with the following statement: “Virtual financial planning meetings can be as productive as in-person meetings.” Possible answers to this question included the five options of strongly disagree, somewhat disagree, neither agree nor disagree, somewhat agree, and strongly agree. Answers were coded as a categorical variable of 1–5, with strongly disagree as 1 through strongly agree as 5. A t-test was conducted to compare the means between the populations of clients and financial planners.

Technology Self-Efficacy

The second level of analysis for this study focused on the relationship between a client’s or planner’s confidence in technology use and perspective on the productivity of virtual meetings. As measures of confidence in technology use, both groups were asked the following two questions: “Considering virtual meeting platforms, how confident are you in (a) Navigating virtual meeting platforms and (b) Troubleshooting problems that may arise in using your preferred virtual meeting platform.” The answers to these questions included the five options of not confident at all, sightly confident, moderately confident, very confident, and extremely confident. These answers were coded into a dichotomous variable of low confidence (not confident at all, sightly confident, and moderately confident) and high confidence (very confident and extremely confident). Similarly, for ease of interpretation, the productivity scale answers were coded into three categories: not productive (strongly disagree and somewhat disagree), neutral (neither agree nor disagree), and productive (somewhat agree and strongly agree). Ordered probit models were executed using the productivity question as a dependent variable and the two confidence questions as independent variables (labeled Navigating and Troubleshooting in Tables 3 and 4, respectively). The control variables of age, income, gender, sex, race, relationship status, and education were added to the model to control their influence on the dependent variable. All variables are coded to enter the model categorically.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Descriptive statistics for the survey sample are shown in Table 1. In this combined sample of planners and clients, the average age is 40.7, with the majority falling within the 25–34 (31.9 percent) and 35–44 (40.8 percent) age categories. The gender breakdown is 59.9 percent male, 40.0 percent female, and <1 percent other. The majority of the sample is straight (90.1 percent), White (86.7 percent), and married (83.1 percent). As might be expected, the mean income for the sample is quite high: over 78.5 percent of the sample made greater than $100,000 per year. The sample is also highly educated, with 81.3 percent having a college degree and 22 percent of that group having a graduate or professional degree. Regarding the variables of interest for this study, 65.5 percent of the sample agree (i.e., somewhat and strongly agree) that virtual financial planning meetings can be as productive as in-person meetings. The sample is more confident in their ability to navigate virtual meeting platforms (64.8 percent answering very or extremely confident) than troubleshooting problems with virtual meeting platforms (39.4 percent answering very or extremely confident).

Quantitative Analysis

Productivity perspectives t-test. The results of the t-test comparing the two perspectives on the productivity of virtual meetings between clients and financial planners are shown in Table 2. This test aims to evaluate whether there is a significant difference in the means between the two groups; the null hypothesis assumes no difference in the means. Results show there is a significant difference in the means between clients (mean = 3.50, SD = 0.83) and planners (mean = 3.88, SD = 0.95) and call for the rejection of the null hypothesis at the p < 0.01 level. The practical interpretation of this result is that planners are more likely to think virtual meetings will be productive than clients.

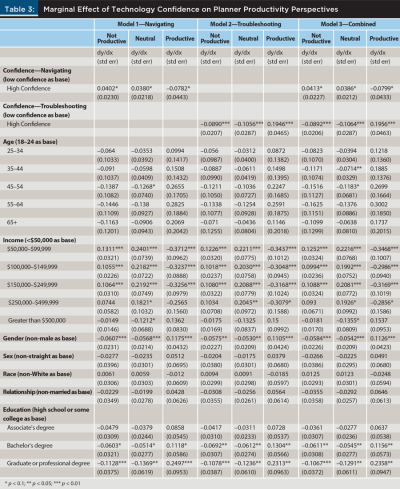

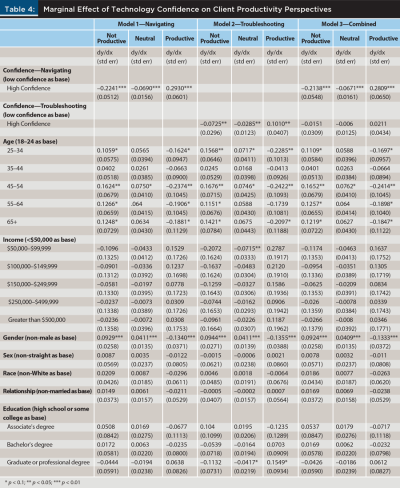

Productivity perspectives ordered probit models. The results of the ordered probit models comparing the two perspectives on the productivity of virtual meetings between clients and financial planners are shown in Table 3 for clients and Table 4 for planners. Models for confidence in navigating and troubleshooting technology were considered separately (Models 1 and 2) and jointly (Model 3) for a total of six models across the two groups. The six models have likelihood ratio chi-squares at the p < 0.005 level, showing all are significant overall compared to a model with no predictors. For the joint client model (Model 3), client results show a significant, positive relationship between high confidence in troubleshooting virtual environments and the view that these meetings can be as productive as in-person meetings. Surprisingly, this model also demonstrated a negative relationship between high confidence in navigating virtual environments and the view that virtual meetings can be as productive as in-person meetings, but this result was only significant at the higher threshold of p < 0.1. The narrative appears to flip for planners. The joint planner model (Model 3) results show a significant, positive relationship between troubleshooting virtual environments and the view that these meetings can be as productive as in-person meetings. However, when the confidence variables are considered separately (Models 1 and 2), both variables show a significant, positive relationship with the view that virtual meetings can be as productive as in-person meetings.

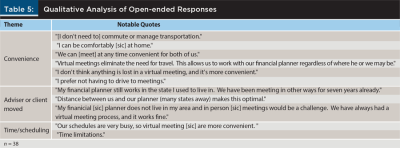

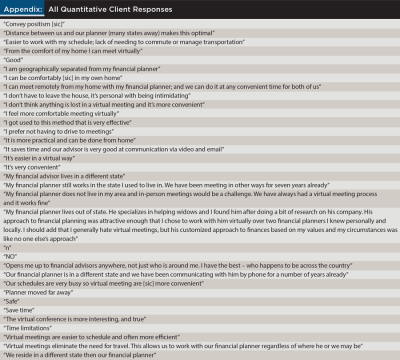

Qualitative Analysis

This study’s survey offered an additional opportunity for clients to answer an open-ended question regarding whether they preferred virtual or in-person meetings. Only 7.8 percent of the sample responded to the open-ended question. This low response rate introduces a bias that requires a strong caveat that these results are not generalizable; they do, however, offer an opportunity to understand why clients might prefer virtual meetings. Of the 34 respondents to the open-ended question, 94.1 percent indicated a preference for virtual meetings. Quotes were clustered thematically and are presented in Table 5. Additional research could shed light on if these themes exist outside of the study’s sample.

Discussion

The results of this study’s t-test suggest that planners are more likely than clients to think virtual meetings will be more productive than in-person meetings. This potential mismatch could lead advisers to become overconfident in the efficacy of this communication channel. Current neuroscience research suggests that digital faces do not stimulate the brain as effectively as person-to-person communication (Connolly 2023). This is interesting because, in the open-ended responses, clients almost unanimously described having a real desire for virtual planning offerings by their planners, citing factors such as convenience, efficiency of scheduling, and adapting to relocation. This aligns with the theory of polymedia, which suggests that access, availability, and affordability are essential predictors of technology effectiveness (Madianou and Miller 2012). Perhaps the low response rate for the open-ended questions on the survey means that there is a subsection of clients who passionately demand virtual engagements, whereas those who are neutral or prefer in-person are not as motivated to provide a rationale. More research will be needed to make any real interpretations of these results, but the differences in perspective could have important implications for the adoption and effectiveness of virtual financial planning services.

The results of the ordered probit models demonstrated the two confidence variables in question (i.e., proxies for technology self-efficacy) had a significant positive relationship with the belief in virtual meeting productivity, with the previously discussed and surprising exception of confidence in navigating virtual environments for clients. This suggests that planners who are comfortable and proficient in virtual meeting platforms may be more inclined to view these meetings as effective alternatives to traditional in-person interactions. This is in line with prior research on technology self-efficacy. It involves confidence in performing tasks, navigating digital tools, and acquiring new technological skills. High technology self-efficacy leads to motivation, exploration of new technologies, and effective technology use, while low self-efficacy may result in frustration and avoidance (Gatti, Brivio, and Galimberti 2017).

When investigating the technology self-efficacy variables separately (confidence in navigating virtual environments versus confidence in troubleshooting), some interesting differences arise between planners’ and clients’ responses. In the planners’ responses, the joint variable model (Model 3) showed a significant positive relationship between planners’ confidence in navigating virtual environments and their belief that virtual meetings can be as productive as in-person meetings. On the other hand, the joint variable model for clients showed confidence in troubleshooting virtual environments was positively related to the belief in virtual meeting productivity. This suggests that clients may prioritize the ability to handle technical issues during virtual meetings. Clients confident in troubleshooting problems with virtual meeting platforms may perceive virtual meetings as productive, possibly because they feel equipped to address any technical difficulties that may arise. However, these clients may not require the same skill level necessary for the planner, who has broader responsibility for the virtual experience in the client–planner relationship.

Implications

These findings have important implications for financial planners. Clients have expressed a desire for virtual financial planning services, with some even stating that they would seek out planners who offer virtual sessions even if the planner is not located in their local area. This desire is likely due to the convenience and flexibility that virtual services offer and the fact that virtual planning can be just as effective as in-person planning (Madianou and Miller 2012). However, clients also hesitate regarding the ability of these meetings to be productive. For planners, this highlights the need to prepare for virtual meeting success. To this end, planners should send out clear agendas to bolster the benefits of a virtual planning meeting. The agenda should include the meeting purpose, goals, and takeaways, similar to the advice provided by Archuleta et al. (2021). This paper describes the need to keep virtual meetings more streamlined with predetermined points in the agenda while also highlighting the need to reiterate points more often online, as it is more difficult to provide others with undivided attention in this environment (versus in-person).

The finding that clients felt virtual meetings were less productive than in-person was also impacted by both the client’s and the planner’s ability to navigate the platform and troubleshoot. Planners must ensure mastery of technology to increase their own perceived productivity while also ensuring that the client has confidence in their ability to troubleshoot problems with their virtual environment (e.g., sending out pre-meeting instructions, walk-through videos, providing IT support phone numbers, etc.). Archuleta et al. (2021) recommended that planners do a mock virtual session with a colleague to observe themselves in a virtual context. A mock virtual session can help practitioners discover where they may need more education or training. In the end, it is important to recognize that technology issues experienced in the virtual client meeting may influence the client’s perception of the productivity of the meeting and, therefore, the planner–client relationship.

Another key takeaway is that although many clients want the option for virtual financial planning, it is not mandatory for all client relationships. Planners with lower technology self-efficacy may focus on developing a client base that prefers in-person sessions as they may perform better in person than online. Similarly, assessing clients’ technology self-efficacy is crucial to determine if virtual financial planning suits them. By matching the preferred mode of interaction to clients’ technology capabilities, planners can enhance the overall client experience and increase the likelihood of successful financial planning outcomes for each unique client.

Limitations

Although this study had important implications, there are limitations to note. Several concerns look at the generalizability of the results. Not unlike many studies in personal financial planning, the sample skewed toward White, male, and high-income individuals. This tends to be the same demographic skewness found in financial planners and clients (Reiter, Seay, and Loving 2022) and limits how the results can be applied to the general population. This research was meant to be exploratory, and results could be bolstered by additional research focusing on replication and more robust qualitative data-gathering. Specifically, future research could gather more data on the motivations behind why clients might prefer virtual meetings, as the sample size for our qualitative analysis was relatively small.

Although our analysis shows that planners are more likely to think virtual meetings will be productive than clients, additional study of this phenomenon is warranted to understand additional implications for financial planners. The mean values between clients (3.50) and planners (3.89) both fall between “Neither agree nor disagree” and “Somewhat agree” on the measurement scale.

Finally, this data was collected during the pandemic, which likely influenced the results. Time will tell if the various relationships studied here have “stickiness” for clients and planners. The results may differ once respondents journey further from the pandemic.

Conclusion

Long-distance client relationships can be maintained and improved through virtual interaction. Our findings highlighted a meaningful relationship between confidence in navigating technology platforms and troubleshooting issues and the perceived productivity of the meeting. Planners should be well-versed in troubleshooting simple technical issues to increase client confidence in the system. However, it is critical to recognize that virtual meetings are not for every client. While some clients prefer this medium, it is best to carefully choose the method of communication based on individual client preferences. Perceived productivity may be higher for planners than for clients. This should cause planners to pause and ensure they are not relying too heavily on technology. Aligning each client’s personal preferences with the form of communication is a best practice and demonstrates to the client that the planner is willing to service the relationship in the best way possible. To this end, advisers should strive to become experts in virtual and in-person communication to keep up with evolving client preferences.

Citation

Collier, Nathan, Jason N. Anderson, Darin Carroll, and Megan McCoy. 2024. “Comparative Perspectives on Virtual Financial Planning: Similarities and Differences between Planner and Client’s Assessments of Virtual Client Meetings.” Journal of Financial Planning 37 (4): 58–73.

References

Ahmad, Alay, and Triantoro Safaria. 2013. “Effects of Self-Efficacy on Students’ Academic Performance.” Journal of Educational, Health and Community Psychology 2 (1): 22–29. https://doi.org/10.12928/jehcp.v2i1.3740.

Ahmad, Farhan, Robert Wysocki, John J. Fernandez, Mark S. Cohen, and Xavier Simcock. 2021. “Patient Perspectives on Telemedicine during the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Hand 18 (3): 522–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/15589447211030692.

Archuleta, Kristy, Sarah Asebedo, Dorothy Durband, Stephen Fife, Megan Ford, Blake Gray, Meghaan Lurtz, Megan McCoy, Jaclyn Pickens, and Gerald Sheridan. 2021. “Facilitating Virtual Client Meetings for Money Conversations.” Journal of Financial Planning 34 (4): 82. www.financialplanningassociation.org/article/journal/APR21-facilitating-virtual-client-meetings-money-conversations.

Arning, Katrin, and Martina Ziefle. 2009. “Different Perspectives on Technology Acceptance: The Role of Technology Type and Age.” In Lecture Notes in Computer Science 20–41. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-10308-7_2.

Bai, John, Erik Brynjolfsson, Wang Jin, Sebastian Steffen, and Chi Wan. 2021. “Digital Resilience: How Work-From-Home Feasibility Affects Firm Performance.” National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w28588.

Bandura, Albert. 1977. “Self-Efficacy: Toward a Unifying Theory of Behavioral Change.” Psychological Review 84 (2): 191–215. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295x.84.2.191.

Boehm, Katharina, Stefani Ziewers, Maximilian Peter Brandt, Peter Sparwasser, Maximilian Haack, Franziska Willems, Anita C Thomas, Robert Dotzauer, Thomas Höfner, Igor Tsaur, Axel Haferkamp, and Hendrik Borgmann. 2020. “Telemedicine Online Visits in Urology During the COVID-19 Pandemic—Potential, Risk Factors, and Patients’ Perspective.” European Urology 78 (1): 16–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2020.04.055.

BiriŞÇi, Salih, and Ümit Kul. 2019. “Predictors of Technology Integration Self-Efficacy Beliefs of Preservice Teachers.” Contemporary Educational Technology 10 (1): 75–93. https://doi.org/10.30935/cet.512537.

Brynjolfsson, Erik, John J. Horton, Adam Ozimek, Daniel Rock, Garima Sharma, and Hong-Yi TuYe. 2020. “COVID-19 and Remote Work: An Early Look at US Data.” NBER Working Paper (June 220): 1–30. https://doi.org/10.3386/w27344.

Calton, B., N. C. Abedini, and M. D. Fratkin. 2020. “Telemedicine in the Time of Coronavirus.” Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 60 (1): e12–e14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.03.019.

Chan, Xi Wen, Sudong Shang, Paula Brough, Adrian Wilkinson, and Changqin Lu. 2022. “Work, Life and COVID-19: A Rapid Review and Practical Recommendations for the Post-Pandemic Workplace.” Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources 61 (2): 257–76. https://doi.org/10.1111/1744-7941.12355.

Connolly, Bess. 2023, October 27. “Zoom Conversations vs In-Person: Brain Activity Tells a Different Tale.” Neuroscience News. https://neurosciencenews.com/zoom-conversations-social-neuroscience-24996/.

Corry, Michael, and Julie Stella. 2018. “Teacher Self-Efficacy in Online Education: A Review of the Literature.” Research in Learning Technology 26 (0). https://doi.org/10.25304/rlt.v26.2047.

Dorsey, E. Ray, and Eric J. Topol. 2020. “Telemedicine 2020 and the next Decade.” The Lancet 395 (10227): 859. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30424-4.

Frost, Riodran. 2021, November. “Have More People Moved During the Pandemic?” Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University. www.jchs.harvard.edu/blog/have-more-people-moved-during-pandemic.

Gatti, Fabiana Maria, Eleonora Brivio, and Carlo Galimberti. 2017. “‘The Future Is Ours Too’: A Training Process to Enable the Learning Perception and Increase Self-Efficacy in the Use of Tablets in the Elderly.” Educational Gerontology 43 (4): 209–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/03601277.2017.1279952.

Holden, Heather, and Roy Rada. 2011. “Understanding the Influence of Perceived Usability and Technology Self-Efficacy on Teachers’ Technology Acceptance.” Journal of Research on Technology in Education 43 (4): 343–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2011.10782576.

Hollander, Judd E., and Brendan G. Carr. 2020. “Virtually Perfect? Telemedicine for Covid-19.” The New England Journal of Medicine 382 (18): 1679–1681. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmp2003539.

Jan, Shazia K. 2015. “The Relationships between Academic Self-Efficacy, Computer Self-Efficacy, Prior Experience, and Satisfaction with Online Learning.” American Journal of Distance Education 29 (1): 30–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/08923647.2015.994366.

Kari, Kingdom. 2020. “Predictors of the Utilization of Digital Library Services among Women Patrons in Bayelsa State, Nigeria: The Moderating Role of Marital Status.” Ianna Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies. www.iannajournalofinterdisciplinarystudies.com/index.php/1/article/view/56.

Lemon, N., and S. Garvis. 2015. “Pre-service Teacher Self-efficacy in Digital Technology.” Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice 22 (3): 387–408. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2015.1058594.

Madianou, Mirca, and Daniel Miller. 2012. “Polymedia: Towards a New Theory of Digital Media in Interpersonal Communication.” International Journal of Cultural Studies 16 (2): 169–87. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367877912452486.

Mitchell, Uchechi A., Perla Chebli, Laurie Ruggiero, and Naoko Muramatsu. 2018. “The Digital Divide in Health-Related Technology Use: The Significance of Race/Ethnicity.” Gerontologist 59 (1): 6–14. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gny138.

Nadler, Joel T., and Katie M. Kufahl. 2014. “Marital Status, Gender, and Sexual Orientation: Implications for Employment Hiring Decisions.” Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity 1 (3): 270–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000050.

Nittari, Giulio, Ravjyot Singh Khuman, Simone Baldoni, Gopi Battineni, Ascanio Sirignano, Francesco Amenta, and Giovanna Ricci. 2020. “Telemedicine Practice: Review of the Current Ethical and Legal Challenges.” Telemedicine Journal and E-Health 26 (12): 1427–1437. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2019.0158.

Parnaby, Patrick. 2011. “Health and Finance: Exploring the Parallels between Healthcare Delivery and Professional Financial Planning.” Journal of Risk Research 14 (10): 1191–1205. https://doi.org/10.1080/13669877.2011.587887.

Pellas, Nikolaos. 2014. “The Influence of Computer Self-Efficacy, Metacognitive Self-Regulation and Self-Esteem on Student Engagement in Online Learning Programs: Evidence from the Virtual World of Second Life.” Computers in Human Behavior 35 (June): 157–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.02.048.

Rahman, Mohammed Sajedur, Myung Ko, John E. Warren, and Darrell Carpenter. 2016. “Healthcare Technology Self-Efficacy (HTSE) and Its Influence on Individual Attitude: An Empirical Study.” Computers in Human Behavior 58 (May): 12–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.2.0116.

Reiter, Miranda, Martin C. Seay, and Ajamu C. Loving. 2021. “Diversity in Financial Planning: Race, Gender, and the Likelihood to Trust a Financial Planner.” Financial Planning Review 5 (1). https://doi.org/10.1002/cfp2.1134.

Riddell, W. Craig, and Xueda Song. 2017. “The Role of Education in Technology Use and Adoption: Evidence from the Canadian Workplace and Employee Survey.” Industrial and Labor Relations Review 70 (5): 1219–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/0019793916687719.

See-To, Eric Wing Kuen, Savvas Papagiannidis, and J. Christopher Westland. 2014. “The Moderating Role of Income on Consumers’ Preferences and Usage for Online and Offline Payment Methods.” Electronic Commerce Research 14 (2): 189–213. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10660-014-9138-3.

Sensenig, Derek, Brian Walsh, Ives Machiz, Matthew Russell, and Megan McCoy. 2020. “Utilizing What We Know About Tele-Mental Health in Tele-Financial Planning: A Systematic Literature Review.” Journal of Financial Planning 33 (9): 48–58. www.financialplanningassociation.org/article/journal/SEP20-utilizing-what-we-know-about-tele-mental-health-tele-financial-planning-systematic.

Wang, Lanting, and M. Obaidul Hamid. 2022. “The Role of Polymedia in Heritage Language Maintenance: A Family Language Policy Perspective.” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development November: 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2022.2142233.

Wejnert, Barbara. 2002. “Integrating Models of Diffusion of Innovations: A Conceptual Framework.” Annual Review of Sociology 28 (1): 297–326. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.28.110601.141051.