Journal of Financial Planning: October 2013

With interest rates now rising from historically low levels, it is more crucial than ever for municipal bond investors to be diligent in the coordination of investment income and tax filing to avoid overpayment; a common mistake made with bonds bought at a premium. Depending on the unique circumstances of each investor impacted by this, incorrect filing could cost hundreds, if not thousands, of dollars per year.

The potential impact varies depending on the state of residency: some states do not tax municipal bond interest at all, some tax interest only for out-of-state municipal bonds, and others tax all municipal bonds regardless of locality. (Check with your state’s department of revenue for details on how your state taxes interest. Also, InvestingInBonds.com summarizes taxation for each state.) For investors who own bonds subject to state income taxation, attention to the premiums paid is necessary to avoid over taxation.

According to IRS Publication 550, if a bond yields tax-exempt interest, you are required to amortize the premium (for bonds issued after September 27, 1985). In doing so, each year you must reduce your basis in the bond (and the corresponding tax-exempt interest otherwise reportable on Form 1040, line 8b) by the amortization that year. The problem is that many 1099s are issued to investors including the full amount of interest received without the offset of amortization, which when included would reduce the overall level of income reported on line 8b of the 1040. Some 1099s will include a supplemental section with amortization disclosed; however, it is not reported to the IRS and would instead need to be picked up by the tax preparer.

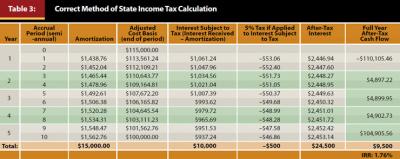

There also is a capital gain or loss implication for bonds sold prior to issuer redemption. Because the cost basis of bonds purchased at a premium must be amortized each year, if sold, the adjusted cost basis—as opposed to original cost basis—must be used to determine gain or loss data. Table 3 includes a column titled “Adjusted Cost Basis (end of period),” which illustrates the declining cost basis from purchase until maturity. If the bond in this example were sold at the end of year three instead of being held to maturity, the investor would calculate their gain or loss using a cost basis of $106,165.82, instead of the $115,000 cost at the time of purchase.

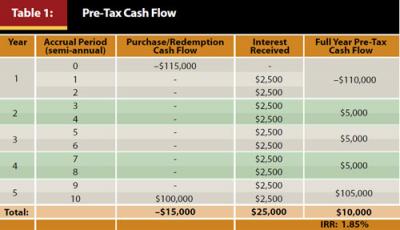

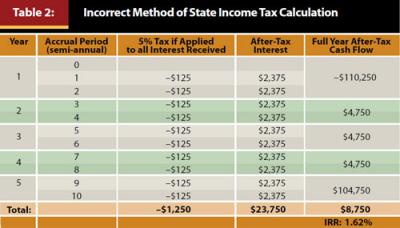

Below is an example illustrating the importance of proper amortization recognition. The investor in this scenario bought a bond at a 1.85 percent yield-to-maturity that if properly amortized, would result in an after-tax IRR of 1.76 percent (Table 3). Conversely, had the investor simply reported the income received without the premium offset, the after-tax IRR would drop to 1.62 percent (Table 2), which is 0.14 percent lower and equates to $750 over the five-year holding period. (Because this bond pays interest semi-annually, the amortization method chosen also was semi-annual to match up with the dates income was due to be received. The amortization was calculated per the IRS guideline for tax-exempt bonds to use a constant yield method.)

Example: An investor living in a state that collects income tax on out-of-state municipal interest buys a bond subject

to same.

- State income tax rate: 5 percent

- Years until maturity: 5 years (non-callable)

- Coupon: 5 percent (paid semi-annually)

- Purchase price: $115.00 ($115,000 per $100,000 of face value)

- Face value: $100,000

- Yield-to-maturity: 1.85 percent

Calculating Amortization and Premium: The Constant Yield Method

Step 1: Determine your yield. Typically, the adviser or broker would provide this information at the time of purchase. The yield must be constant over the term and go to at least two decimal places when expressed as a percentage.

Step 2: Determine the accrual periods. You have flexibility in choosing the accrual periods to use; however, it is typically easiest to use the same schedule to which the bond pays interest payments. The accrual period cannot exceed one year.

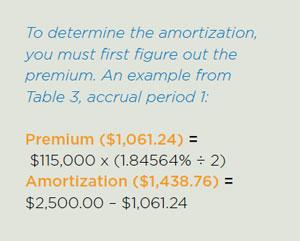

Step 3: Determine the bond premium and amortization for the accrual period using these formulas:

Premium = aP x (Y ÷ n)

Amortization = Interest – Premium

Where,

Interest is qualified stated interest for the period (for example, 5 percent interest paid semi-annually on $100,000 par value would equal $2,500 per period);

aP is adjusted acquisition price at the end of the accrual period. When a bond is first purchased, the

aP equals the cost basis. After the first calculation period, the basis is adjusted down by bond premium amortization from the prior periods (see Table 3).

Y is yield at purchase (1.84564 percent in the example);

n is number of accrual periods (for example, two for semi-annual).

Conclusion

In today’s uncertain rate environment, it is more important than ever to help clients keep more of what they earn. Investors who own municipal bonds that are subject to taxation should refer to IRS Publication 550 to determine the proper way to account for income and amortization over time.

William R. Collins IV, CFP®, CRPC®, is a practicing CFP professional and member of FPA of New York. Contact him by clicking HERE.