Journal of Financial Planning: October 2013

Randy Gardner, J.D., LL.M., CPA, CFP®, is a professor of tax and estate planning at the University of Missouri–Kansas City and an education specialist for the WealthCounsel Companies. He is co-author (with Julie Welch) of 101 Tax Saving Ideas and co-author (with Leslie Daff) of The Closing Wealth Transfer Window. (Email HERE).

Matt McClintock, J.D., is vice president of education for the WealthCounsel Companies and a featured speaker at www.estateplanning.com. (Email HERE).

Leslie Daff, J.D., is a state bar certified specialist in estate planning, probate, and trust law and the founder of Estate Plan Inc., a professional law corporation with offices in California and Kansas. (Email HERE).

Julie Welch, CPA, CFP® is director of tax and a shareholder with Meara Welch Brown PC in Kansas City, Missouri. (Email HERE).

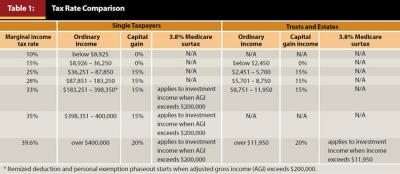

The 39.6 percent ordinary tax rate and 20 percent capital gain tax rate enacted by the American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012 (ATRA), and the 3.8 percent Medicare investment surtax now apply when trust income exceeds $11,950. These high rates apply at much lower levels of income for trusts than for individual taxpayers (see Table 1). With this disparity in mind, grantors creating trusts and trustees managing trusts should consider some strategies.

Income Distributed by a Trust Is Deductible

There are two broad types of trusts: grantor trusts and nongrantor trusts. Grantor trusts are ignored for tax purposes, and an individual grantor pays tax on the income earned by the assets in the trust on their personal Form 1040.

Nongrantor trusts are taxable entities for which the trustee must file a tax return (Form 1041).

Trusts are taxed similar to individuals, except that they are conduit entities like partnerships and S corporations. Income distributed by the trustee to beneficiaries is taxable to the beneficiaries and deductible by the trust. Income is taxed either at the trust level or the beneficiary level, but not both.

For example, the Mary Jones irrevocable trust received $25,000 of interest and dividend income. The trust paid $7,500 in trustee fees and $500 for the preparation of its income tax return. The trustee has the discretion to distribute the $17,000 ($25,000 – $7,500 – $500) of net income to the individual beneficiaries, Sam and Deb, or retain the income in the trust. Aware that the tax rates applicable to the income retained in the trust exceed the rates applicable to Sam and Deb, the trustee distributes the income to Sam and Deb to be taxed on their personal returns. The trustee reports the distribution to Sam and Deb on a Trust K-1. The trust has reduced its income and tax to zero for the year.

Trust Distribution Planning Strategies

- The trustee should take advantage of deductions at the trust level before determining the amount to be distributed to the beneficiaries. Typical deductions include the trust’s often-wasted $100 exemption deduction, transaction costs, and appraiser, accountant, attorney, and fiduciary fees.

- If the beneficiaries are subject to tax, but not at the highest rates, the trustee can spread the income between the trust and the beneficiaries, adjusting the distribution to minimize the tax at the trust and beneficiary levels. For example, if Sam and Deb pay tax at the 25 percent marginal tax rate, the trustee can take advantage of the 15 percent marginal tax rate applicable to the trust by retaining $2,450 of net income in the trust.

- If the beneficiaries are dependents of their parents and the amount of investment income attributable to them exceeds $2,000, the beneficiaries may be subject to their parents’ tax rate because of the “kiddie tax.” If the parents are at the maximum tax rate, the kiddie tax eliminates the benefit of distributing income from the trust to the beneficiaries.

- Trustees have 65 days after the trust year-end (usually March 6) to think through these strategies, calculate the optimal distribution strategy, and make the distributions to the beneficiaries.

What about Capital Gain Income?

Since its original issuance in 1931, 45 states have adopted some version of the Uniform Principal and Income Act (UPAIA). Under UPAIA, capital gains are generally allocated to principal, while interest income and dividends are treated as income.

To illustrate the significance of this, assume a trust that is required to distribute income receives $25,000 of dividend income and recognizes $15,000 of capital gain income from trading securities. The trust will distribute the $25,000 of dividend income to be taxed on the beneficiaries’ personal returns. However, the trust will pay tax on the $15,000 of capital gain income. Because the capital gains exceed $11,950, part of the gain will be subject to the maximum 20 percent capital gain rate and the 3.8 percent Medicare investment surtax.

Although UPAIA provides default allocations of income and principal, the defaults can be overridden by the language of the trust.

This provision provides an excellent opportunity for grantors establishing trusts, trustees managing trusts, and trust protectors amending trusts to add language that gives trustees the flexibility to minimize the impact of the current high tax rates. Sample language that might be added to a trust is:

“Our Trustee shall determine how all Trustee fees, disbursements, receipts, and wasting assets will be credited, charged, and apportioned between principal and income in a fair, equitable, and practical manner. Our Trustee may allocate capital gain to income rather than principal.”

Giving the trustee the power to distribute capital gain income to a lower-income beneficiary rather than accumulating it as principal in the trust subject to the high trust income tax rates could save the family 8.8 percent of the capital gain if the beneficiary is subject to the 15 percent capital gain rate and 23.8 percent if the beneficiary is subject to the 0 percent capital gain rate.

Asset Protection

Over the past few decades, clients have flocked to discretionary trusts that hold all property in trust, often for many generations, allowing the trustee to make distributions that are not subject to an “ascertainable standard.” The prevailing argument in favor of creating these discretionary trusts is that because the beneficiaries’ interests are not limited to an ascertainable standard, there is nothing for a creditor to attach a judgment against. Although there are a few exceptions in some jurisdictions, discretionary trusts created by a grantor for the benefit of another beneficiary are incredibly powerful asset-protection vehicles.

However, there is an expensive tradeoff between retaining all income in a trust and providing the protections offered by a discretionary trust. If the trust retains the income during a taxable year, the trust may be subject to the maximum income tax rate plus the Medicare surtax. On the other hand, if the trust makes a distribution to the beneficiary, that distribution becomes the beneficiary’s property and is exposed to potential claims of a creditor. In years that a trust beneficiary has low exposure to creditors, it likely makes sense for the trustee to make distributions to the beneficiary to take advantage of the beneficiary’s individual tax rate. If the beneficiary is at a higher risk of creditor attachment, the trustee must consider whether the risk of attachment outweighs the tax liability of the income retained in the trust.

It is easy to see why selecting the right trustee is essential for a successful plan.