Journal of Financial Planning: October 2013

Executive Summary

- This paper proposes a conceptual learning and development model for financial planning organizations called the University for Practitioners, which is based upon the well-established and highly regarded notion of the corporate university.

- A corporate university is a term that encompasses an organized method of training and developing employees in the culture of a business enterprise.

- An effective model to unite training and development initiatives into a system that aligns learning with organizational goals is absent within the literature.

- The model described in this paper was designed to assist in the development of a competitive marketing advantage for recruiting and retaining top-quality talent that helps financial planning firms align “hiring and talent development with their vision and structure” (Tibergien 2011).

- The University for Practitioners concept provides the framework, mindset, and mark of distinction required to develop and sustain a culture of lifelong learning and commitment to excellence.

Sarah Asebedo, CFP®, is a shareholder and director at Accredited Investors Inc. She is pursuing a doctorate in personal financial planning and a certificate in conflict resolution through Kansas State University. She serves on the board of directors for the Financial Therapy Association and is a member of FPA. (Email HERE)

Gabriel Asebedo, CFP®, CSP, is the owner of Perennial Wealth Group, Inc., a multi-generational family wealth advising company emphasizing family governance systems to pass family values to successive generations inheriting financial wealth. (Email HERE)

The top two critical human resource functional areas that determine an organization’s business strategy, according to the Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM 2008), are staffing/employment/recruitment (52 percent) and training/development (29 percent). The financial planning literature discusses each of these areas to varying degrees. These topics are of interest to business owners who are nearing the critical crossroads associated with transitioning their organizations to the next generation.

Although the financial planning literature discusses learning and development, it leaves a tangible and practical model that unites employee learning initiatives with organizational goals largely unexplored. The purpose of this paper aligns with the second most critical functional area, training and development of existing employees, and seeks to offer a conceptual learning and development model for financial planning organizations based upon the well-known and highly regarded corporate university concept traditionally found in corporate America.

Applying the Corporate University Model to Financial Planning Organizations

The notion of a corporate university is a rather recent phenomenon. In essence, a corporate university is a term that encompasses an organized method of training employees in the culture of a business enterprise. Many of the world’s leading corporations, both large and small, have found that the introduction of systematic training and education approaches increases efficiencies, employee effectiveness, and maximization of strategic goals.

In this paper, firm size is defined as the number of employees based on FPA’s 2012−2013 Financial Planning Compensation Study:

Small = 1 to 5 employees

Mid-sized = 6 to 30 employees

Large = 31 or more employees

A vital goal of a corporate university is to operationalize employee learning and development initiatives to attain key organizational goals and to facilitate employee movement along a career path. When organizational goals are aligned with career paths and learning functions, the organization as a whole, and the people within it, can be more successful.

Career path development within the financial planning profession has long been recognized as a key to the success of organizations and employees alike. Career path development particularly has been a challenge for smaller firms. Most (1998) showed that financial planning organizations have typically been smaller and more entrepreneurial in nature with few advancement opportunities, which has resulted in career path development challenges. However, the growth of financial planning organizations over time has produced more innate layers that can be harnessed to provide the career paths needed to retain talent.

Joinson (1997) discussed the benefits of multiple career paths, as opposed to the traditional corporate career ladder, as a way to promote employee retention and provide more options for employee growth and satisfaction (other than traditional management positions). Joinson posited that there must be appropriate tools and infrastructure in place to support multi-directional career paths for employees to have a clear sense of available opportunities.

Guyton (2001) called for the financial planning profession to build “the landmarks and infrastructure that will eventually become key stepping stones along future career paths.” Tibergien (2011) built on this theme and argued that the best performing advisory businesses have a human capital plan that aligns hiring and talent development with their vision and structure. This infrastructure, as highlighted by Guyton, combined with a human capital plan, are critical to providing a tangible course of action for career paths and aligning employee aspirations with the goals of the organization.

Grote (2009) mentioned the concept of a university within a financial planning organization when he highlighted Abacus Planning Group’s in-house university. According to Grote, Abacus Planning Group’s “employees take turns teaching weekly seminars covering everything from using irrevocable life insurance trusts to making good first impressions.” Teaching others is a critical part of learning, however it is just one part of a greater learning and development initiative.

While the conversation on career path development continues, this paper focuses on the tools and infrastructure to support career path development that is innately linked to the goals and growth of the organization.

Five Areas for Success

The diversity of successful corporate university models and the funding and support needed from senior management begs the question: what are the key areas that make a corporate university, and by extension a University for Practitioners, function successfully?

Li and Abel (2011) sought to answer this question by analyzing 210 corporate universities across industries and geographies in North America. The results of their study suggest the following five essential strategic areas: (1) alignment and execution, (2) development of skills that support business needs, (3) evaluation of learning and performance, (4) use of technology to support the learning function, and (5) partnership with academia. These five areas provide the foundation for applying the corporate university model to a financial planning organization through a University for Practitioners platform.

Introducing the University for Practitioners Model

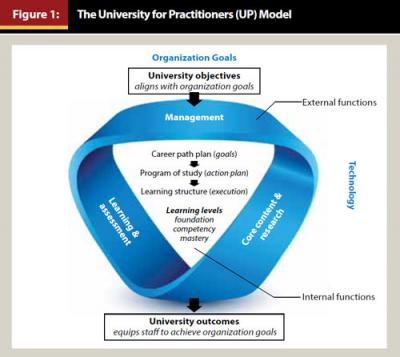

Although almost all financial planning firms share common themes in terms of anticipated client outcomes, certainly cultural, structural, and other need-based variables will differentiate one University for Practitioners from another. Figure 1 provides a pictorial representation of the University for Practitioners model.

University for Practitioners (UP) and corporate universities are ongoing, continuous institutions effecting positive change on the organization and its people. To pictorially represent infinite learning in this context, the UP uses the symbol for infinity, which is known as the Möbius Strip. The Möbius Strip was discovered in 1858 by German mathematicians August Ferdinand Möbius and Johann Benedict Listing, and is known for the way in which someone can travel from the outer to the inner side in one continuous movement without crossing any edges (Pickover 2006). The Möbius Strip appears to have two sides to it; however, in reality it has only one side. It is a quintessential symbol that demonstrates how the topic areas of the UP are intertwined and connected with both the inward and outward functions of a financial planning organization. Furthermore, the “oneness” of the strip symbolizes the connection of the university with the overarching goals of the organization.

External Functions

Management. Management serves as the alignment and execution essential strategic area of a corporate university (Li and Abel 2011), aligning the UP’s learning objectives with the goals of the organization and executing these learning objectives to attain the targeted outcomes.

Goal alignment is critical to the learning initiatives pursued through the UP. The management function provides oversight and accountability to ensure alignment exists between learning objectives and the organization’s goals. Moreover, the management function ensures the UP is effectively functioning as a system to ensure appropriate integration of all areas and that stated outcomes are achieved. This includes oversight for the culture and synergy of learning collaboration across the UP and the organization.

The management function also serves an internal and external marketing purpose. “The CU (Corporate University) label often suggests the strategic importance that a company has on the employee learning and development function” (Li and Abel). The conceptualization of a learning and development program exemplifies the value and resources allocated toward existing employees, thus having a positive impact on retention and attraction of key and top-quality talent. The management function is responsible for driving marketing initiatives and promoting the UP internally and externally, ensuring the desired impact of the program is realized.

Learning and Assessment. Learning and assessment (L&A) encompasses employee learning and development needs, in addition to providing assessment for each learning module and collaborative learning initiative against the stated outcomes. The L&A function serves as the “evaluation of learning and performance” essential strategic area of a corporate university (Li and Abel 2011).

The learning function involves several different programs, including building and maintaining learning modules within the UP, guiding the program of study for new talent joining the organization (new hire on-boarding program), identifying the resources for or directing the creation of curriculum and learning modules needed to fill identified development gaps, determining outsourcing opportunities for learning tools and resources, and developing learning tools and resources within the organization.

The assessment function can be used to evaluate the effectiveness of learning initiatives and curriculum, in addition to partnering with performance management to identify developmental gaps. The assessment team may include members of the human resources department or the performance management group, depending on the structure of the organization. Assessment is essential to identifying how the UP needs to adapt to a changing environment to stay on the cutting edge of learning and, therefore, maintain the organization’s competitive advantage.

Core Content and Research. Core content and research (CC&R) delivers technical knowledge to the UP, and facilitates the “development of skills that support business needs” (Li and Abel 2011) and partnerships with those in academia, both of which are essential strategic areas of a corporate university.

Core content and research also facilitates the creation of internal subject matter expertise. Many different content areas exist within financial planning, and it can be difficult, if not impossible, to be an in-depth expert in all of them. Consider the Certified Financial Planner Board of Standards Inc.’s (CFP Board 2012) Principal Topics List that includes 78 topics related to financial planning, organized into the following areas: general principles of financial planning, insurance planning, investment planning, income tax planning, retirement planning, estate planning, interpersonal communication, and professional conduct and fiduciary responsibility.

Through CC&R, each topic area relevant to the organization is identified and assigned according to interest, talent, and development needs. It is essential for topic areas to strategically align with employee’s interests, skill sets, and development opportunities to optimize employee engagement, maximize talent, and retain employees (Herbers 2012). Each topic area is developed through education and experience until mastery is attained. At its full functioning capability, CC&R is able to educate internally through the UP and provide in-depth, cutting-edge expertise to support and provide a competitive edge to the client service offering.

The CC&R function also incorporates the partnership of outside expertise related to each content area. This outside expertise is typically provided by accountants, attorneys, mortgage brokers, insurance agents, and those in academia. The primary purpose of aligning with outside expertise is to provide implementation and strategic planning support throughout the planning process. This outside expertise also acts as support to the UP by providing collaboration within the learning function.

Research and publication are relevant and critical areas of the CC&R function from both an academic and practitioner perspective. Buie and Yeske (2011) discussed the role of academic research in building the financial planning profession. Specifically, they proposed “that the time has come to commit ourselves as a profession to a more scientifically grounded and evidence-based approach to expanding our body of knowledge and assessing and adopting best practices.” If financial planning is to develop into a true profession, then academic research needs to be considered as the underpinning to the strategies and recommendations of the financial planning profession.

Furthermore, practitioner perspectives are highly valued and critical to meaningful and practical application of proposed strategies and research. It would be difficult to stay current with all of the academic research and practitioner publications that exist within the literature. Therefore, the CC&R function also serves as the area that partners with academia, other practitioners, and outside experts to come together to stay abreast of relevant research and strategies in each specific content area.

Although the primary idea is to embrace and incorporate academic and practitioner literature into practice, an additional option within the CC&R function is to produce relevant contributions to the academic and practitioner literatures. The CC&R function creates vast opportunities for career path growth within financial planning organizations due to the focus on area specialization, and potentially academic and practitioner research and publication.

Internal Functions

Career Path Plan. Meaning and direction are at the epicenter of consequential progress and change, and thus, a career path plan is an essential component of any effective UP. Several practitioner papers have asserted the need for career paths in financial planning (Buttell 2009; Grote 2005; Guyton 2001; Herbers 2005; Most 1998; Tibergien 2011). The UP recognizes the significance of having a long-term plan in place that guides goal development and, consequently, provides direction and meaning.

Every financial planning organization is unique and may require an equally distinctive career path plan for employees. Regardless of the form a career path plan takes, a clear and actionable plan permits goals to be created that fully align with the desired direction of one’s professional development.

Program of Study. A program of study (POS) traditionally has been used in academic settings to guide the education curriculum required to complete a specific degree track. In essence, the POS is simply an action plan that guides one along the path to the achievement of a specific goal. The POS is the action plan in the UP that provides the framework for the composition and organization of learning modules, clearly defining the timeframe, learning level, and purpose of each learning focus.

Learning Structure. A key purpose of a UP is to facilitate the learning process, individually and across the organization. Li and Abel (2011) stated that “an important mission for Corporate Universities is to support organizational goals and major initiatives by operationalizing the employee learning and development function.”

A certain flow of learning occurs naturally within financial planning organizations. As planning ideas and alternatives are developed and executed, energy is built, great planning occurs, and profound learning takes place. The natural flow of learning must be harnessed and effectively disseminated across the organization to maximize the development process and enrich learning outcomes.

The UP harnesses the flow of learning through two primary components: collaborative learning and learning modules.

The underlying premise of collaborative learning is connecting with others to facilitate the learning process. The purpose of collaborative learning is twofold. First, bringing two or more people together facilitates the dissemination of technical knowledge and expertise across the organization, bringing about conceptual change and growth individually and collectively and, thereby, building knowledge depth and enhancing service offerings to clients. Second, collaborative learning provides the space to create shared meaning, which cements the desired culture within the organization.

Collaborative learning has been shown within the literature to build a shared vision and provide the platform to constructively address conflict and ultimately develop and cement shared meaning across an organization (Roschelle 1992; Van den Bossche et al. 2011). The UP has a substantial focus on collaborative learning, given the need for ongoing knowledge development and the delivery of financial planning by people with diverse backgrounds and opinions. Financial planning philosophy alignment and the dissemination of financial planning knowledge are essential to the financial planning organization and can be accomplished through collaborative learning.

Learning modules are designed to support the cognitive development function, providing the tools necessary for ongoing conceptual change. As referenced in the Li and Abel (2011) study, alignment with organizational goals is essential to organizational learning and therefore, the UP.

Learning modules should be developed in alignment with organizational goals to maximize the effectiveness and permanence of the university. The UP model proposes that all learning modules incorporate (1) clear learning objectives, providing the basis for future assessment; (2) collaboration, as described above; (3) practical application for hands-on learning;

and (4) assessment to determine the effectiveness of the module compared with the learning objectives and alignment with the organization’s goals. Furthermore, learning modules should leverage technology and outside resources as much as possible for efficiency.

Progression within the UP is based on compounding levels of growth. Learning levels may vary in number and direction depending upon each specific organization’s needs; however, three levels are generally requisite: (1) foundation, (2) competency, and (3) mastery.

The foundation learning level is critical to anyone entering the organization. The foundation learning objectives are the “must haves” to function within the organization and within the specific job description of the employee. An example of a foundation learning module may be “Introduction to Company Culture” or “Essential Communication Skills.” These modules have a focus on becoming independent and self-functioning within the employee’s job description and as a member of the organization.

The competency level builds on foundational strengths by providing learning resources and objectives that home in on obtaining role proficiency within the organization. For the financial planner, this may mean being able to conduct a client meeting or facilitate a conversation among multiple parties.

The mastery level focuses on learning objectives and resources that may impact the broader organization, the financial planning profession, and multiple levels of staff within the firm, such as management, networking, research and publication, conflict resolution, and other factors. This may mean mastering the art of establishing new client relationships, writing for professional publications, or managing a department. An employee’s specific growth plan may vary depending upon the staff member’s career track and goals, and may include learning modules from each different level of the UP. Because learning modules and levels within the UP are tied to the goals and characteristics of the organization, these will be innately unique across organizations.

Putting It into Practice

The UP is designed to be flexible and scalable. While the core external functions (management, core content and research, and learning and assessment) exist in every UP, the execution components (for example, the who, what, and how) vary depending upon organizational needs and size. A hypothetical mid-size financial planning company will be used to explore the practical application and implementation of the UP concept.

Management Team at Financial Planners Corp.

Jane and Paul are the owners of Financial Planners Corp. and have decided to implement the basic functions of a UP in their firm. They have formed a management team (MT) that includes Paul and two senior staff members. Jane and Paul categorize their company as a mid-size firm, yet realize that Financial Planners Corp. is on the smaller end of the spectrum. They have determined the best allocation of owner/employee resources is to have only one owner present on the MT in an effort to manage time constraints and reduce undue influence on MT decisions and anticipated outcomes. Their hope is to transition MT control and responsibility to qualified employees over time, while reducing owner involvement to key decisions only.

As conceptualized, the MT is charged with UP oversight, which includes strategic goal alignment (UP with the organization), accountability for outcomes, culture integration, and marketing. The ownership group typically defines the strategic goals of the organization and the available career paths within. The MT works closely with the ownership group to accomplish the critical tasks outlined previously.

MT key players will vary across organizations depending on size and available talent; however, the MT most likely will be comprised of internal resources only. Internal resources, such as owners, senior leadership, and other key employees have direct in-depth knowledge of the people within the organization, day-to-day operations, procedures, and culture, which make internal resources more appropriate than external resources to conduct UP management functions.

The smaller the organization, the more the owner(s) may need to be involved. Larger organizations have greater flexibility to transition management functions to qualified employees. This transition would occur over time as the owner(s) step back and give more responsibility to qualified employees. In the case of Financial Planners Corp., the individuals held accountable for the UP are Paul and two senior staff members.

Learning and Assessment at Financial Planners Corp.

It is important that Jane and Paul critique their options for employee involvement when developing and facilitating the learning and assessment program. They determined their two most senior planners are qualified to influence what is needed to help company owners and employees develop and meet the goals outlined by the MT’s strategic vision.

Given that Financial Planners Corp. already has a sizeable budget for employee continuing education, Jane and Paul have decided to funnel those monetary resources into the learning and assessment program and use external resources to fill the company’s core learning needs. The two senior planners are responsible for building the overall curricula program based on the MTs strategic vision using education resources available from FPA and colleges and universities that teach financial planning and other related proficiencies (for example, conflict management and communication skill development).

The program is categorized into three learning levels (foundation, competency, and mastery). The two senior staff members oversee the assessment of employee development by conducting monthly role plays based on actual client situations.

In this example, the company has developed a moderately strict regimen of continuing education requirements, new skill acquisition, and examination to determine progress and proficiency.

The objective of the learning and assessment team is to develop employees through identified resources, promote mastery of identified content, effectively implement new knowledge and skills into daily workflow, and determine successes and failures through assessment of both curricula and employee. The hypothetical company, Financial Planners Corp., was able to leverage an already existing, and possibly extensive, budget.

Most financial planning firms, small or large, have existing educational budgets to works with; however, smaller firms will likely have greater difficulty creating and managing learning and assessment programs due to (1) limits on the availability/allocation of time, (2) budget constraints that prevent implementation of costly external resources for all employees, and (3) limited availability of internal resources, including staff and technology.

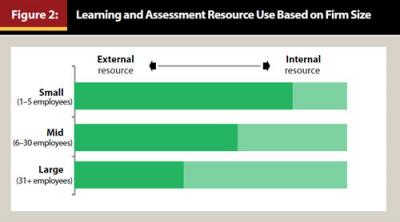

It is important to note that flexibility in selecting between external and internal resources, as well as the potential efficient use of resources, improves as a firm grows in size, with larger firms continuing to leverage external resources as much as possible and as appropriate. Figure 2 illustrates how use of internal resources versus external resources may vary for the learning and assessment function, according to an organization’s size.

Core Content and Research at Financial Planners Corp.

Jane and Paul want to develop a core content and research program within their UP. Without a core content and research program, a university model within a financial planning firm loses much of its uniqueness. To achieve the organization’s strategic goal of providing in depth comprehensive financial planning, they recognize that the first step involves developing subject matter expertise within their staff. They have aligned their staff’s interests as much as possible and assigned one person to each of the CFP Board’s Principal Topics List areas. Each planner is responsible for incorporating academic and practitioner literature into client planning strategies and providing learning tools for each specific planning area within the UP.

During discussions, Jane and Paul concluded that they have a strong desire to have a robust research arm capable of producing white papers or perhaps publishing groundbreaking studies in peer-reviewed journals. Paul especially enjoys the thought of marketing Financial Planners Corp.’s research prowess to current clients and prospects. Jane remains stumped on how to do this. Jane has concerns about negative media exposure due to flawed research. Her examination of staff capabilities (while developing the learning and assessment program) has left her in doubt about Paul’s overly optimistic use of the firm’s research to win over new clients. In an attempt to address this issue, Jane has decided to meet with one senior and one junior staff member in an effort to determine the feasibility of building an active research arm into their core content and research program.

During the meeting, Jane and the senior staff member get wrapped up in a conversation about use of materials from their custodian and mutual fund companies’ white papers as a means to introduce more advanced technical depth to the firm. The junior planner added to the dialogue by suggesting a partnership with the local university where financial planning is taught. Based on this recommendation, they agree that incorporating outside experts to ensure technical quality and accuracy would be beneficial.

As a result, Jane called a local university’s program director, who said he was too busy to participate personally, but he had a number of graduate students and perhaps one financial planning faculty member who might be willing to discuss this idea further. Jane scheduled a visit to the campus and was able to work out a partnership with the financial planning program graduate students, with one tenured professor providing oversight and guidance to the research projects with an aim for publication. Jane also had a conversation with one of the firm’s trusted estate planning attorney colleagues who was excited about the idea of contributing to research with the potential for publication.

Financial Planners Corp. was able to successfully implement a framework to develop subject matter expertise, incorporate practitioner and academic literature into their planning strategies, and develop a strategic research partnership within their UP core content and research program. External resources were primarily leveraged through a local university and an existing estate planning expert network, while internal staff resources were used to spearhead the development and oversight of each topic area. Strategic partnerships can function in a similar pattern for each core content area of financial planning.

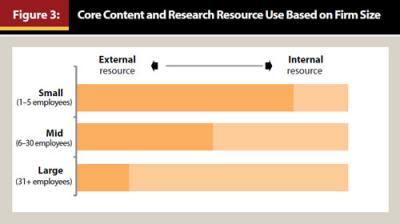

Figure 3 represents how external versus internal resources may be leveraged depending on an organization’s size. Larger organizations have greater flexibility to bring resources and expertise in-house; however, larger firms may choose to continue to leverage external options.

Summary

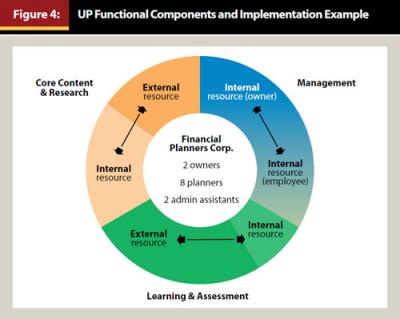

Figure 4 summarizes the various functional components found in a prototypical UP, such as the one Financial Planners Corp. implemented. The figure also shows how internal and external resource implementation may vary for each area.

Conclusion

This paper has endeavored to conceptualize a learning and development model based on existing literature and research that meets the unique needs of financial planning organizations that will endure and adapt over time as organizations evolve. The notion of a corporate university served as a foundational model for this paper.

The UP model, as presented here, was developed based on Li and Abel’s (2011) research, which surveyed 210 American corporate universities across industries and conducted statistical analyses that resulted in the five essential strategic areas of focus for a corporate university. Given the resources needed to develop an effective learning and development program, Li and Abel’s study provides an anchor to ground and guide the development of a UP program.

Although the idea of a university may seem rigid, it is meant to be flexible. One size clearly does not fit all, as each financial planning organization can be as unique as one individual is to another. Thus, the UP is not a mold that an organization must fill. It is a lifelong learning and development model that is shaped to fit the unique financial planning organization, adjusting over time as growth and change occur.

It is important to remember that a corporate university system is not reserved for large firms exclusively. Of the 210 corporate universities in Li and Abel’s (2011) study, 50 percent of those surveyed had less than 25 full-time employees. As previously mentioned, corporate universities are meant to be flexible and tailored to meet specific needs and goals, which will vary depending upon a variety of factors, including the size of an organization. Effective use of technology can be critical in leveraging a university’s efficiency for large and small organizations alike. A consistent theme throughout the literature is that e-learning is critical when considering how to leverage a university’s resources. A UP can be tailored based on the size, talent pool, and strategic goals of each unique financial planning organization.

The financial planning profession is a helping profession, and as such, lifelong learning is critical to the growth trajectory of financial planners and financial planning organizations alike. The traditional training model does not adequately support this lifelong learning initiative. Corporate America has seen many of the benefits associated with adopting the notion of a corporate university, which provides the framework, mindset, and mark of distinction required to develop and sustain a culture of lifelong learning and commitment to excellence.

Researchers and practitioners who are interested in this topic can have a significant impact on the future development of UPs. Of particular importance is the need for a more detailed implementation framework that financial planning firms can use to execute a university system. Other opportunities for exploration include developing assessment standards and tools for program outcomes and building a national network of UP faculty who are willing to share educational tools and techniques.

References

Buie, Elissa, and Dave Yeske. 2011. “Evidence-based Financial Planning: To Learn...Like a CFP.” Journal of Financial Planning 14 (11): 38–43.

Buttell, Amy E. 2009. “Navigate Your Way Through the Career Path Forest.” Journal of Financial Planning 22 (10): 22–29.

Certified Financial Planner Board of Standards Inc. 2012. “Principal Topics List.” www.cfp.net/become-a-cfp-professional/cfp-certification-requirements/education-requirement/principal-topics.

Grote, Jim. 2005. “Exploring Career Paths in Financial Planning.” Journal of Financial Planning 18 (8): 36–43.

Grote, Jim. 2009. “The Soft Skills.” Financial Planning 39 (12): 51.

Guyton, Jonathan T. 2001. “Blazing Financial Planning’s Career Paths.” Journal of Financial Planning 14 (4): 150–154.

Herbers, Angie. 2005. “Power Shift.” Investment Advisor 25 (7): 43–44.

Herbers, Angie. 2012. “Young Guns: How to Keep Valuable New Employees for the Long Term.” Investment Advisor 32 (10). www.advisorone.com/2012/10/23/young-guns-how-to-keep-valuable-new-employees-for.

Joinson, Carla. 1997. “Multiple Career Paths Help Retain Talent.” HR Magazine 42 (10): 59–64.

Li, Jessica, and Abel, Amy L. 2011. “Prioritizing + Maximizing the Impact of Corporate Universities.” T+D Magazine 65 (5): 54–57.

Most, Bruce. 1998. “Looking for a Few Good Men and Women: Staffing Issues for Financial Planning Practices.” Journal of Financial Planning 11 (5): 48–56.

Pickover, Clifford A. 2006. The Mobius Strip: Dr. August Mobius’s Marvelous Band in Mathematics, Games, Literature, Art, Technology, and Cosmology. New York, New York: Thunder’s Mouth Press.

Roschelle, Jeremy. 1992. “Learning by Collaborating: Convergent Conceptual Change.” The Journal of the Learning Sciences 2 (3): 235–276.

Society for Human Resource Management. 2008. HR’s Evolving Role in Organizations and Its Impact on Business Strategy. Alexandria, Virginia: SHRM Research Department.

Tibergien, Mark. 2011. “It’s Not About You.” Investment Advisor 31 (8). www.advisorone.com/2011/07/28/its-not-about-you.

Van den Bossche, Piet, Wim Gijselaers, Mien Segers, Geert Woltjer, and Paul Kirschner. 2011. “Team Learning: Building Shared Mental Models.” Instructional Science 39 (3): 283–301.

Citation

Asebedo, Sarah, and Gabriel Asebedo. “The University for Practitioners: A Conceptual Learning and Development Model.” Journal of Financial Planning 26 (10): 50–59.