Journal of Financial Planning: May 2021

William Reichenstein, Ph.D., CFA, is head of research at Social Security Solutions, Inc., and Retiree, Inc., and Professor Emeritus at Baylor University. He has published more than 190 articles and written several books, including Social Security Strategies, 3rd Edition (2017) with William Meyer, and Income Strategies (2019).

William Meyer is CEO of Retiree, Inc. in Overland Park, Kansas. He and William Reichenstein developed software to combine a smart Social Security claiming decision with a tax-efficient withdrawal strategy (www.incomesolver.com).

JOIN THE DISCUSSION: Discuss this article with fellow FPA Members through FPA's Knowledge Circles.

FEEDBACK: If you have any questions or comments on this article, please contact the editor HERE.

NOTE: Please click on the images below for PDF versions.

This report presents important insights related to the optimal Social Security claiming age for a single individual. The first section demonstrates that in order to maximize expected real (inflation-adjusted) lifetime Social Security benefits, it is seldom optimal for a single retiree to claim benefits in any month near either of two dates. The first date is 36 months prior to the full retirement age (FRA), while the second date is the FRA.

The second section discusses four other factors that the single retiree should consider when selecting their claiming age. Each of these factors should encourage single individuals to delay claiming Social Security beyond this lifetime maximizing age.

The report then explains when the lessons from the first section related to maximizing a single retiree’s expected real lifetime benefits also apply to the claiming strategy for each partner of a married couple. As the reader will see, the lessons for single retirees apply to the claiming strategy for some married couples, but not for others.

Maximizing Expected Real Lifetime Benefits for Singles

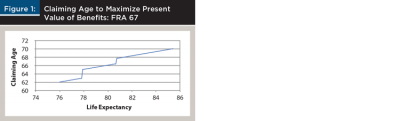

This section examines the claiming age that would maximize a single individual’s expected real lifetime benefits. Reichenstein and Meyer (2017) and Meyer and Reichenstein (2010) both examined the claiming age that would maximize the present value of expected lifetime benefits. However, most clients better understand the analyses when the comparison of claiming strategies is couched in terms of expected real lifetime benefits.

For example, suppose a single client will receive monthly benefits of $2,000 if begun now at her FRA. If inflation is 2 percent, then she will receive $2,040 per month next year, but the cost of goods and services will be 2 percent higher as well. Since cost-of-living adjustments (COLAs) are designed to keep the purchasing power of her monthly benefits constant, this real lifetime benefits framework presents her monthly benefits as a constant $2,000 per month for the rest of her life.

This report begins by explaining how the Social Security Administration set the reduction in retirement benefits (i.e., benefits based on the claimant’s earnings record) for beginning benefits before FRA, and the delayed retirement credits (DRCs) for delaying benefits until after FRA. The primary insurance amount (PIA) denotes the benefits amount if benefits are begun at FRA. The reduction in benefits for beginning benefits before FRA is 5/9 percent of PIA for each of the first 36 months that retirement benefits begin before FRA, plus 5/12 percent of PIA for each additional month. The DRCs are 2/3 percent of PIA for each month that benefits are delayed beyond FRA to age 70.

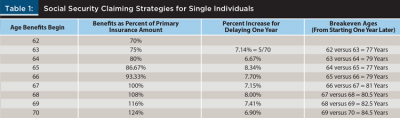

The second column of Table 1 presents the monthly benefits amount as a percent of PIA for someone born January 2, 1960, or later, and thus someone who has an FRA of 67. If she begins her retirement benefits at age 67, they will be 70 percent of her PIA. From 62 until 64 (that is, until 36 months before her FRA), her benefits level increases by 5/12 percent of PIA per month (5 percent per year) that she delays benefits. At 64, her benefits amount is 80 percent of her PIA. From age 64 until FRA, her benefits level increases by 5/9 percent of PIA per month (6 2/3 percent per year) that she delays benefits. At FRA, her benefits amount is 100 percent of her PIA. From FRA until age 70, her benefits level increases by 2/3 percent per month (8 percent per year) that she delays benefits. Thus, the additional benefits for delaying her retirement benefits one more month increases from 5/12 percent to 5/9 percent of PIA 36 months before attaining FRA and then increases from 5/9 percent to 2/3 percent of PIA at her FRA. Due to these increases for delaying the start of benefits one more month at 36 months before FRA and at FRA (with two exceptions), she would never maximize her real lifetime benefits by starting her benefits anywhere near these two dates.1

This section presents the claiming strategy that would maximize expected real lifetime Social Security benefits for a single retiree with an FRA of 67, where expected benefits are based on current promises of the Social Security system.

Delaying the start of Social Security benefits from age 62 to 63 increases the monthly benefits from 70 percent to 75 percent of PIA. The breakeven age between starting benefits at age 62 or 63 is 77 years.2 Although not shown in Table 1, the breakeven age between starting benefits at age 62 and 62 and one month is 76 years and one month. Thus, to maximize expected real lifetime benefits, only single individuals with unusually short life expectancies should begin their benefits as soon as possible.

From Table 1, the breakeven age between starting benefits at 63 or 64 is 79.

At age 64 (36 months before FRA), the additional benefits for delaying the start of Social Security benefits one more month increases from 5/12 percent to 5/9 percent of PIA per month. Thus, delaying the start of Social Security benefits from age 64 to 65 increases the monthly benefits from 80 percent of PIA to 86 2/3 percent of PIA. This represents an 8.34 percent increase in monthly benefits (i.e., 6.67 percent/80 percent), which Table 1 indicates is the largest percent increase from delaying the start of benefits one more year. Recognition of this important point is recent, so it has not been discussed in previous works from the authors. Due to this large increase, the breakeven age between starting benefits at 64 or 65 falls to 77. Although not shown in Table 1, no one would maximize real lifetime benefits by starting benefits within 12 months on either side of this 36-months-before-FRA date.

From Table 1, the breakeven age between starting benefits at 65 and 66 is 79, while the breakeven age between starting benefits at 66 or 67 is 81.

At FRA of 67, the additional benefits for delaying the start of Social Security benefits one more month increases from 5/9 percent to 2/3 percent of PIA per month. Thus, delaying the start of Social Security benefits from age 67 to 68 increases the monthly benefits from 100 percent of PIA to 108 percent of PIA. The breakeven age between starting benefits at 67 or 68 is 80.5 years. Although not shown in Table 1, no one (who is not affected by the earnings tests) would maximize real lifetime benefits by starting benefits within eight months on either side of FRA.

The breakeven age between starting benefits at 68 and 69 is 82.5, while the breakeven age between starting benefits at 69 or 70 is 84.5. Although not shown in Table 1, the breakeven age between starting benefits at age 69 and 11 months and 70 is 85 years and five months. Thus, to maximize expected real lifetime benefits, a 62-year-old single individual with an FRA of 67 and a life expectancy of at least 85 years and five months should delay claiming Social Security benefits until age 70.

In short, these single individuals with a life expectancy of 76 years and one month or shorter would maximize their expected real lifetime benefits by beginning those benefits at age 62 (or as soon as possible if already older than 62). If these single individuals have a life expectancy of 85 years and five months or longer, then they would maximize their expected real lifetime Social Security benefits by delaying those benefits until age 70.3

Furthermore, because the reductions in benefits for starting benefits before FRA and the increases in benefits for delaying benefits until after FRA are the same for people with other FRAs, the following statements apply to all single retirees. To maximize real lifetime benefits, no one should claim their Social Security benefits any time between 12 months before and 12 months after this 36-month-before-FRA date. Similarly, to maximize expected lifetime benefits, no one (not affected by the earnings tests) should claim their Social Security benefits any time between eight months before and eight months after their FRA.

Statements like, “He waited to file until his FRA, so he could get his full benefits,” are common. Such statements seem to suggest that FRA is a natural age to claim Social Security benefits. As this report shows, for most single individuals, there is nothing natural about starting Social Security benefits anywhere near their FRA.

Other Criteria That May Influence Social Security Claiming Age

In 1983, the Social Security Administration set the reductions in benefits for beginning benefits before FRA and the DRCs for delaying benefits until after FRA to be approximately actuarially fair for a single retiree with a then-average life expectancy, assuming a real risk-free Treasury rate of 3 percent. The prior section examined the claiming strategy that will maximize a single individual’s expected real lifetime benefits. However, there are four reasons why a single retiree today may wish to delay the start of his or her benefits beyond this real lifetime benefits maximizing age.

First, most retirees are also concerned about minimizing longevity risk; that is, the risk of depleting their financial portfolio during their lifetime. Since longevity risk is highest if the retiree lives longer than expected, to minimize this risk a single retiree may choose to delay Social Security benefits until after the age that would maximize his or her expected real lifetime benefits.

Second, the average life expectancy is longer today than in 1983. According to Munnell and Chen (2019), the life expectancy for a 65-year-old person in 1983 was 17 years, while it is 20.4 years in 2020.

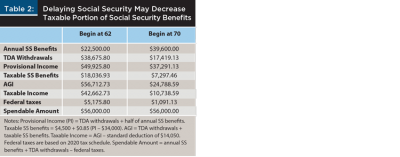

Third, as Reichenstein and Meyer (2018) and Reichenstein (2019) illustrated, many middle-income retirees—both single individuals and married couples filing jointly—can reduce the taxable amount of their Social Security benefits by delaying the beginning of those benefits. Table 2 illustrates this logic for a single individual, but the same logic applies to married couples.

This single individual is in her 70s and will spend $56,000 of after-tax income in 2020. Her PIA is $2,500 and her FRA is 66. In the Begin-at-62 Strategy, she began her retirement benefits at 62 and in 2020, her annual Social Security benefits will be $22,500, (75 percent x $2,500 x 12 months). To attain her spending goal, she could withdraw $38,675.80 from her tax-deferred account [e.g., 401(k)] and she would pay $5,175.80 in taxes.4 This would allow her to meet her $56,000 spending goal, ($56,000 = $22,500 + $38,675.80 – $5,175.80).

In the Begin-at-70 Strategy, she delayed her Social Security benefits until 70. Her annual benefits in 2020 would be $39,600, (132 percent x $2,500 x 12 months). To attain her spending goal, she would only need to withdraw $17,491.13 from her TDA. She would pay $1,091.13 in taxes.

The key insight is that provisional income (PI)—the measure of income used to calculate the taxable portion of her Social Security benefits—includes all of her TDA withdrawals, but only half of her Social Security benefits. As a first approximation, the additional $17,100 of Social Security benefits by delaying allows her to reduce TDA withdrawals by $17,100. But since this substitution lowers her PI by $8,550, it lowers the taxable portion of her Social Security benefits by up to 85 percent of this amount and, thus, lowers her taxes. This reduction in taxes allowed her to reduce her TDA withdrawals by more than $17,100, which further reduces both the taxable portion of her Social Security benefits and taxes. In this example, the net result from delaying the start of her Social Security benefits was a $17,100 increase in these benefits, an approximately $21,200 reduction in TDA withdrawals, and an approximately $4,100 decrease in taxes. By delaying the start of Social Security benefits, she reduced the taxable portion of these benefits by about $10,740.

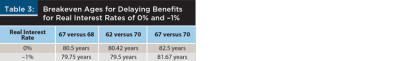

Fourth, today’s real yield on 10-year Treasury TIPS is about –1 percent.5 Today’s exceptionally low interest rates encourage delaying the start of Social Security benefits beyond the age that would maximize real lifetime benefits. As shown in Tables 1 and 3, based on a real yield of 0 percent, the breakeven age between starting Social Security benefits at FRA of 67 or 68 is 80.5 years. From Table 3, based on today’s real yield of –1 percent, the breakeven age—that is, when the present values of real benefits from starting these benefits at 67 or 68 are equal—is nine months earlier at age 79.75 years.

From Table 3, based on a real yield of –1 percent, the breakeven age between starting benefits at 62 or 70 is 11 months sooner than if the real yield is 0 percent. Based on a real yield of –1 percent, the breakeven age between starting benefits at 67 or 70 is nine months sooner than if the real yield is 0 percent. For obvious reasons, previous writings from Reichenstein and Meyer did not discuss how today’s record-low interest rate environment would impact a single individual’s Social Security claiming decision.

In summary, although this report examines the claiming age that would maximize expected real lifetime benefits, this is not the only criterion that can be used when deciding on a Social Security claiming age. Consideration of each of four other criteria would encourage a later claiming age.

Implications for Married Couples

This section examines how, if at all, the lessons from the prior analysis for single retirees should apply to the claiming decisions of married couples. The analyses for married couples changed with the changes in Social Security rules in November 2015. Thus, the conclusions on this issue as presented in Meyer and Reichenstein (2012) are not always applicable today.

After the rule changes, there is a different set of rules affecting what this report calls Group 1 individuals (people born January 1, 1954, or earlier), and Group 2 individuals (people born January 2, 1954, or later). Group 1 individuals can file a restricted application for spousal benefits at their FRA or later if their spouse has already applied for their retirement benefits and later switch to their retirement benefits. In contrast, Group 2 individuals cannot file a restricted application for spousal benefits. Rather, whenever they apply for benefits, they are assumed to be applying for all benefits (e.g., retirement and spousal benefits) for which they are eligible. Whether the lessons for single retirees also apply to married couples depends upon the Group that each married partner is in and sometimes on the relative sizes of their PIAs.

Both spouses in Group 2 and lower PIA ³ half of higher PIA. This section begins by discussing how the analysis for single retirees applies to married couples when (1) both spouses are in Group 2, and (2) the lower-PIA spouse’s PIA is at least half as high as that of the higher-PIA spouse. In this case, neither spouse will receive spousal benefits because their own retirement benefits will be at least as high as their spousal benefits. Thus, retirement benefits based on the higher-PIA spouse’s earnings record (assumed male for clarity) are a second-to-die real lifetime annuity. After the death of the first spouse—and it does not matter which spouse dies first—the survivor will continue benefits based on his record. In contrast, retirement benefits based on the lower-PIA spouse’s earnings record will cease at the death of the first spouse. Thus, real benefits based on the lower-PIA spouse’s earnings record are a first-to-die real lifetime annuity.

Consider Jerry and Jan. Jerry was born September 2, 1958, and has an FRA of 66 years and eight months. He has a PIA of $2,800 and a relatively short life expectancy of 77 years. Jan is three years younger. She was born September 3, 1961, and has an FRA of 67. She has a PIA of $2,000 and her life expectancy is 83 years. Since benefits based on Jerry’s record will last until the second spouse dies, he should delay his benefits until age 70, because he would be 86, if still alive, when Jan is expected to die. In contrast, Jan should begin her retirement benefits as soon as possible (i.e., at age 62 and one month) because benefits based on her earnings record are expected to cease when Jerry dies, when she is 74.6 All dollar amounts are before COLAs.

Let us change the assumptions to make an important point. Suppose Jan and Jerry have life expectancies of, respectively, 86 and 89 years. In this case, to maximize their expected joint real lifetime benefits, they each plan to file for benefits at age 70. In 2025, at age 67, Jerry learns that he has cancer and will only live one more year. How should this affect their claiming decision? The correct answer is that Jan should begin her benefits as soon as possible, while Jerry should not begin his benefits despite his short life expectancy. If Jerry lives one more year then, by not filing for benefits today, Jan will receive 8 percent more per month for an estimated 21 years.

In summary, the lessons from the claiming strategies for single individuals have important implications for these married couples. The relevant life expectancy for the higher-PIA spouse is the age he or she would be when the second spouse is expected to die, while the relevant life expectancy for the lower-PIA spouse is that age he or she would be when the first spouse is expected to die.

Both spouses in Group 2 and lower PIA < half of higher PIA. This section examines the implications, if any, for married couples when (1) both spouses are in Group 2, and (2) the lower-PIA spouse’s PIA is less than half as high as that of the higher-PIA spouse. In this case, this couple’s maximum expected real lifetime benefits claiming strategy may not be the one that applied in the prior example. Rather, it often pays for the higher-PIA spouse to begin his benefits earlier, so that the lower-PIA spouse can receive spousal benefits based on his earnings record for a longer period. The lower-PIA spouse cannot receive spousal benefits until the higher-PIA spouse files for his retirement benefits.

Consider Jan and Jerry again, but this time assume Jan’s PIA is $600. In this case, Strategy 2 maximizes their expected real joint lifetime benefits. In this strategy, Jan begins her retirement benefits at age 62 and one month of $422. At age 69 and four months, Jerry begins his retirement benefits of $3,397 and Jan adds spousal benefits at that time for total benefits of $1,178 per month.7 After Jerry’s death, Jan continues his benefits of $3,397 per month. All dollar amounts are before COLAs.

Let’s compare their benefits in Strategy 2 and Strategy 1. In Strategy 1, Jan files for retirement benefits at age 62 and one month and Jerry files for retirement benefits at age 70. Strategy 2 produces larger lifetime benefits than Strategy 1. In Strategy 2, from age 66 and four months until she turns 67, Jan receives $1,178 per month in combined retirement-plus-spousal benefits instead of only receiving $422 per month in Strategy 1. In addition, from age 69 and four months until age 70 Jerry receives $3,397 per month, compared to receiving no benefits for this period in Strategy 1. These additional amounts more than offset the combination in Strategy 1 of: (1) Jerry’s higher retirement benefits beginning at 70; (2) Jan’s higher retirement-plus-spousal benefits beginning at 67; and (3) Jan’s additional survivor benefits after Jerry’s death. There are a lot of moving parts, but the bottom line is that the lessons concerning when singles should begin their Social Security benefits do not always apply to married couples when: (1) both spouses are in Group 2; and (2) the lower-PIA spouse’s PIA is less than half as high as that of the higher-PIA spouse.

Higher-PIA spouse in Group 1 and lower-PIA spouse in Group 2. As explained here, the lessons for single individuals seldom apply to married couples when the higher-PIA spouse is in Group 1 and the lower-PIA spouse is in Group 2.

Consider Tamara and Tom. Tamara was born September 2, 1958, and is thus in Group 2. She has a PIA of $1,000, FRA of 66 and eight months, and life expectancy of 84. Tom was born September 20, 1953, and is thus in Group 1. He has a PIA of $2,800, FRA of 66, and life expectancy of 84.

As shown in www.ssanalyzer.com software, based on life expectancies, this couple’s expected real lifetime benefits maximizing strategy (Max Strategy) is the following: Tamara files for her retirement benefits of $716 for September 2020, when she attains age 62. At that time, Tom files a restricted application for spousal benefits of $500 per month, which is half of Tamara’s PIA. When Tom attains age 70 in September 2023, he files for his retirement benefits of $3,696 per month, ($2,800 x 1.32), which reflects four years of DRCs, and Tamara adds spousal benefits at that time for total benefits of $1,061.8

Based on the lessons from the singles strategies, they might consider following Strategy 2. In Strategy 2, Tom would delay his retirement benefits until 70, because he would be 89, if still alive, when Tamara dies. To garner spousal benefits as soon as possible, Tamara would begin her retirement-plus-spousal benefits of $1,233 when Tom files at 70 and she is 65.

Based on life expectancies, the Max Strategy offers more real lifetime benefits than Strategy 2. In the Max Strategy, Tamara receives $716, and Tom receives $500 in real benefits for each month from September 2020 until Tom turns 70. This more than makes up for Tamara’s lower monthly benefits when Tom turns 70 until he dies. In short, in general, the lessons from the analysis for singles do not apply to married couples when the higher-PIA spouse is in Group 1 and the lower-PIA spouse is in Group 2.

Both spouses in Group 1. Suppose both spouses are in Group 1 and neither partner has filed for Social Security benefits. For example, suppose both Betty and Bob were each born September 2, 1953. Betty has a PIA of $2,800 and life expectancy of 85, while Bob has a PIA of $2,000 and life expectancy of 82. Let’s compare two of their claiming strategies. In Strategy 1, Bob, the lower-PIA spouse, files for retirement benefits today (April 2020), and Betty files a restricted application for spousal benefits of $1,000, half of Bob’s PIA. At 70, Betty switches to her retirement benefits of $3,696, which reflects four years of DRCs. In Strategy 2, they both file for their retirement benefits at 70. For Strategy 2 to provide more real lifetime benefits, both spouses would have to live to about age 91.5. This outcome is not likely. Thus, the investment lessons for single retirees seldom apply to these married couples.

In short, the lessons for single retirees apply to married couples when: (1) both spouses were born January 2, 1954, or later; and (2) when the PIA of the lower-PIA spouse is at least half as large as the PIA of the higher-PIA spouse. In particular, the higher-PIA spouse should base his or her claiming strategy on the age he or she would be when the second spouse is expected to die, while the lower-PIA spouse should base his or her claiming strategy on the age he or she would be when the first spouse is expected to die. However, these lessons generally do not apply to other married couples.

Summary

This report began by examining the Social Security claiming strategy that will maximize a single individual’s expected real lifetime benefits. In particular, she (assumed female for clarity) should not claim Social Security benefits in any month near either of two dates. The first date is 36 months before her FRA for retirement benefits, while the second is her FRA.

Due to the way monthly benefits levels are calculated, as a general rule, no single individual should begin Social Security benefits (1) between 12 months on either side of the month that is 36 months before her FRA, nor (2) between eight months on either side of her FRA. Furthermore, if the life expectancy of a single individual with FRA of 67 is 76 years and one month or shorter, then she can maximize expected real lifetime benefits by beginning those benefits at age 62 (or as soon as possible if already older than 62). If a single individual’s life expectancy is 85 years and five months or longer, then she can maximize her expected real lifetime Social Security benefits by delaying those benefits until age 70.

We then discussed four other factors that could influence when a single individual would want to claim Social Security benefits. All four of these factors encourage a later starting month than the month that would maximize expected real lifetime benefits. The first factor is the desire to minimize longevity risk. The second factor is today’s longer average life expectancy compare to this average in 1983 when the reductions for beginning benefits before FRA and the DRC for delaying benefits until after FRA were set. The third factor is the reduction in the taxable portion of many middle-income taxpayers’ Social Security benefits from delaying the start of their benefits. The fourth factor is today’s exceptionally low interest rates.

This report then examined when the lessons from the analysis of the Social Security claiming decision for single individuals would apply to married couples. As explained, these lessons apply to married couples if (1) both partners were born January 2, 1954, or later, and (2) the PIA of the lower-PIA spouse is at least half as high as the PIA of the higher-PIA spouse. In this case, the relevant life expectancy for the higher-PIA spouse is the age he or she would be when the second spouse is expected to die, while the relevant life expectancy for the lower-PIA spouse is the age he or she would be when the first spouse is expected to die. Finally, this report explained why the lessons from the analysis of the claiming decision for single individuals generally do not apply to married couples if both conditions do not apply.

Endnotes

- There are two exceptions. First, consider a single individual whose retirement benefits would be eliminated if begun before FRA due to earnings tests. Since earnings tests do not apply once someone retires or attains FRA, a single person with an unusually short life expectancy may maximize lifetime benefits by beginning those benefits at FRA. The second exception would be a single individual who, due to illness, suddenly has a shortened life expectancy. For example, consider a 64-year-old single individual with a life expectancy of 86 years. Due to her life expectancy, she has not begun her Social Security benefits. She suddenly becomes ill today, which shortens her life expectancy to five years. In this case, it makes sense for her to begin her benefits immediately, even though her current age is 36 months before her FRA.

- For a PIA of $1,000, lifetime real benefits for someone who lives to age 77 if benefits begin at 62 are $126,000, [$700 per month x 12 months x (77–62) years], while lifetime benefits if begun at 63 are also $126,000, [$750 per month x 12 months x (77–63) years].

- Due to the pattern of reductions in benefits for starting benefits before FRA and DRC for delaying benefits until after FRA, when the FRA is smaller, the ages at which maximum benefits occur at starting ages of 62 or 70 become longer by the same number of months. For example, for someone with an FRA of 66 years and six months, the maximum benefits occur at age 62 if life expectancy is 76 years and seven months or less, which is six months later than when the FRA is 67. Similarly, at FRA of 66 and six months, the maximum benefits occur at age 70 if life expectancy is 85 years and 11 months or less, which is six months later than when the FRA is 67.

- For simplicity, this report assumed her non-Social-Security funds come from TDA withdrawals. However, the same lesson applies if her non-Social-Security funds come from most other sources of income including pension income, taxable interest, and earned income.

- For a single individual beginning Social Security benefits in her mid-60s, the duration of a fixed real benefit for 20 years is about 10 years. Similarly, the duration of a 10-year TIPS bond when the real yield is near 0 percent is about 10 years. Thus, we use the real yield on 10-year TIPS.

- Jan cannot begin Social Security benefits until the month in which she has “attained” age 62 for the entire month. The Social Security Administration considers someone to “attain” an age one day before their birthday. For example, consider people, like Jan, who were born in September 1961. Someone born September 3 through September 30, 1961, can first receive benefits for the month of October 23; that is, the first month in which they “attained” age 62 for the entire month. Their benefits level will be that of someone age 62 and one month since they “attain” that age in October. Someone born September 1, 1961, can receive benefits for the month of September 2023, but their benefits level is that of someone age 62 and one month since they “attain” age 62 and one month on September 30, 2023. Only someone born September 2, 1961, could begin benefits at their age 62-and-0-month benefits level for the month of September 2023, since they will have “attained” age 62 for the full month. Generalizing, only people born on the second of a month can file for their age 62-and-0-month benefits level.

- Jan’s retirement benefits at age 62 and one month is 0.7042 x $600 = $422.50 then rounded down to $422, where 0.7042 is [1 – {36 x (5/9 percent)} – {23 x (5/12 percent)}] since she began benefits 59 months before her FRA. Her spousal benefits at age 66 and four months (i.e., eight months before her FRA of 67), are $755.56, which after rounding becomes total retirement-plus-spousal benefits of $1,178 per month, [$422.50 + $755.56 then rounded down]. The reduction in her spousal benefits factor is 25/36 percent of PIA per month for eight months, and her maximum spousal benefits are $800, [half of his PIA – her PIA of $600]. Thus, her spousal benefits are $755.56, [94.44 percent of $800, where 94.44 = 1 – {8 x (25/36 percent)}].

- In September 2023, Tamara files for retirement benefits of $716.67 = 0.7167 x $1,000 and then rounded down to a whole dollar, where the 0.7167 reflects her reduced retirement benefits factor due to beginning her retirement benefits 56 months before her FRA, [1 – {36 x (5/9 percent)} – {20 x (5/12 percent)}]. She adds spousal benefits when Tom files for his retirement benefits at 70 and she is 67. Her spousal benefits are $344.44 = ($1,400 - $1,000) x [1 – {20 x (25/36 percent)}]. Her full spousal benefits are $400, [half of the higher PIA – her PIA], which is the spousal benefits level if begun at FRA or later. The reduction from full spousal benefits for beginning these benefits before FRA is 25/36 percent of PIA for the first 36 months that these benefits begin before FRA plus 5/12 percent for each additional month. So, her retirement-plus-spousal benefits total $716.67 + $344.44, which is $1,061 per month when rounded down to a whole dollar.

References

Meyer, William, and William Reichenstein. 2010. “Social Security: When to Start Benefits and How to Minimize Longevity Risk.” Journal of Financial Planning 23 (3): 49–59.

Meyer, William, and William Reichenstein. 2012. “Social Security Claiming Strategies for Singles.” Retirement Management Journal 2 (3): 61–66.

Munnell, Alicia, and Anqi Chen. 2019. “Are Social Security’s Actuarial Assumptions Still Correct?” Center for Retirement Research at Boston College, Technical Report, Chestnut Hill, MA.

Reichenstein, William. 2019. Income Strategies: How to Create a Tax-Efficient Withdrawal Strategy to Generate Retirement Income Leawood, KS: Retiree Inc.

Reichenstein, William, and William Meyer. 2017. Social Security Strategies, 3rd Edition, Retiree Income, Inc.

Reichenstein, William, and William Meyer. 2018. “Understanding the Tax Torpedo and Its Implications for Various Retirees.” Journal of Financial Planning 31 (7): 38–45.