Journal of Financial Planning: June 2015

People use rules of thumb to make their lives more manageable. “You can survive three weeks without food, three days without water, and three minutes without air,” “If your feet are cold, put on a hat,” “Red sky at morning, sailors take warning. Red sky at night, sailors delight."

In the personal finance and investment world, here are some rules of thumb: “Pay yourself first,” “Have X percent of your portfolio invested in stocks, where X is equal to 100 minus your age, with the rest invested in lower-risk investments like bonds” (from Getrichslowly.org, March 9, 2014), “If you expect to withdraw from your portfolio for 40 years or more, you can probably safely withdraw and spend 4 percent of its value every year” (from Work Less, Live More by Bob Clyatt, as cited on Getrichslowly.org; readers of the Journal will recognize this as Bill Bengen’s “4 percent rule”).

The work of Daniel Kahneman, Nobel-prize winning economist, psychologist, and author of Thinking Fast, Thinking Slow, has spread the concept of a rule of thumb called “anchoring bias.” A ship drops anchor at a certain spot, then drifts with the current away from the anchor, but only up to the radius determined by the length of the anchor’s chain. Similarly, an investor might anchor his thinking on a certain statement or idea. From there he adjusts his views, which move away from the point of reference, but only up to a certain distance.

Many people viewed the 2008 market collapse and their own portfolio losses from an anchor reference point of 2007, when portfolios had climbed significantly higher from 2001. This made their distress more acute than if they had anchored on the immediate post-9/11 period.

The anchoring biases of clients who resist sound advice presume intuitive knowledge or instincts that supersede the analyses of a fiduciary. Some anchors are formulated from people’s personal experiences, or even passed down from generation to generation. Some are good guidelines, but others could get clients in trouble. Here are two examples from my experiences.

Anchoring Bias No. 1: The Gut Feeling

“I built this company, and its stock is absolutely, positively going to $20,” claimed Alfie Smith (not his real name). Alfie reached the pinnacle of his wealth with this single stock representing $6 million of his net worth of $14.5 million. At that time, the stock’s price was $14. Like Alfie, many clients anchor on a single stock position and do not take appropriate precautions or diversifiers to hedge their risk.

During the Great Recession, after having previously declined the advice to collar his stock, Alfie’s holding sank from $14 per share to 75 cents in a matter of weeks. The devastation was like a perfect storm. Banks pulled back. Alfie and his wife Betty lacked liquidity and had no meaningful income.

Alfie and Betty were devastated by the loss of their stock. There was a certain level of panic in their household, especially after the real estate market collapsed and there was now a credit crisis. Alfie went back to the couple’s financial adviser to collaborate and to attempt to negotiate new loans on their business debt and various real estate holdings. The properties fell below their level of debt, and banks were holding onto TARP money.

Alfie and Betty had to rethink their entire plan. After some time selling off depressed assets, cancelling permanent insurance policies, commuting charitable trust assets, and getting family counseling, their investable assets for retirement were down to $2 million. Their expectations of receiving $500,000 per year in retirement would now be more like $90,000. This time, Alfie and Betty began to take their financial adviser more seriously.

Anchoring Bias No. 2: Costs vs. Value

A client sees the phrase “no-load mutual fund.” He likes the seemingly low-cost scenario, makes that his anchor, and then evaluates an adviser and the adviser’s recommendations accordingly. This anchoring bias involves a client over-emphasizing visible cost against overall value. It’s like someone with a heart condition having chest pains and going to a walk-in clinic instead of a cardiologist.

One problem with this approach is the invisible costs—like mutual fund trading costs—that most investors aren’t aware of. It’s been shown that “annual trading costs bear a statistically significant negative relation to performance” (Edelen, Evans, and Kadlec 2007, page 5). But a client tells himself: if I’m going to pay a professional for advice, it better be more worthwhile than what I can achieve on my own. So he makes decisions based on visible costs, depriving himself of the added value that qualified advisers can provide.

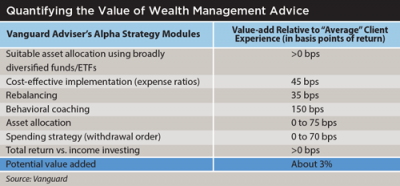

How much added value? Vanguard recently quantified the value of wealth management advice (see the table above), showing a total value added of about 3 percent when considering contributions of an adviser in the areas of rebalancing, behavioral coaching, access to research, strategy, income source selection, etc.

Dealing with Anchoring Biases

At the beginning of a client relationship, some essentials need to be done. An Investment Policy Statement (IPS) should be filled out with objectives, time frames, and required rates of return. Wealth capacity needs to be assessed before assuming risk parameters for the portfolio. A thorough risk analysis needs to be provided (beyond the typical broker-dealer required forms) to indicate an individual’s capacity for and willingness to assume risk.

In addition, anchoring biases should be identified and periodically reviewed. Investors are people, and people have biases that they may not be aware of that could negatively impact their finances. Part of an adviser’s job should be to help clients discover these biases and illuminate their potential consequences. Preferably, a client self-discovers his or her anchoring biases through a questionnaire or quiz, similar to the implicit-association test, which reveals hidden racial or gender biases.

Clients and advisers should have at least one—preferably face-to-face—meeting per year to do a total inventory of assets and financial data. Expectations and assumptions, actual progress, and anchoring biases can be discussed. The IPS and risk analyses should be revisited.

Financial advisers may also need to have a network of experts in behavior modification, life transitions, and generational challenges who could be called in when counseling and life coaching are needed.

Conclusion

One’s portfolio deserves more than a rule-of-thumb approach to wealth. Like the Smiths with their single-stock holding, focusing on a single-year return, or a benchmark with little relevance, or relying on a strongly held gut feeling can result in financial disaster for clients. Likewise, paying attention only to visible costs can result in clients missing out on the additional, measurable value that qualified advisers can contribute.

The stock market does not have a personal objective and risk tolerance. The market does not contemplate one’s intangible aspirations and align them with tangible, measurable resources—excellent advisers do.

Francis X. Astorino, CFP®, CPWA®, has been a practicing financial planner since 1983 and owner of The Astorino Financial Group Inc., a registered investment adviser in New Jersey, since 1986. He is a frequent speaker to professional groups, and as an advocate of total wellness, he pilots workshops with a psychologist for families and couples to augment his practice’s Financial Life Planning Division.

References

Edelen, Roger M.; Richard B. Evans; and Gregory B. Kadlec. 2007. “Scale Effects in Mutual Fund Performance: The Role of Trading Costs.” Available on Social Science Research Network.