Journal of Financial Planning: December 2020

Executive Summary:

- A late-career worker with a choice between pretax and Roth retirement contributions should consider the level of tax-deferred assets already accumulated.

- That asset level affects the worker’s tax rates over the course of retirement, due to required minimum distributions (which may not be needed to support spending), and also affects taxes on beneficiaries.

- This study analyzes the decision for a variety of scenarios by calculating breakeven asset levels (as a multiple of income) where Roth and pretax contribution strategies yield the same after-tax value for beneficiaries.

- Contrary to the conventional view that people in peak earning years should save using pretax contributions, the analysis shows that many people who are well on track for retirement would help their beneficiaries—without sacrificing retirement spending—by choosing the Roth strategy.

- The SECURE Act, passed in late 2019, requires most non-spouse beneficiaries of retirement accounts to withdraw all of the funds within 10 calendar years. That requirement can increase beneficiaries’ tax rates, compared with a “stretch” strategy allowable under prior law.

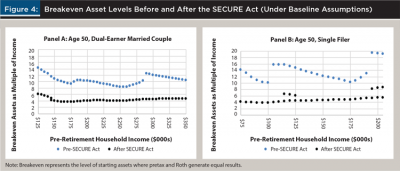

- This study shows that breakeven asset levels are significantly lower after passage of the SECURE Act, indicating that more people would benefit from a Roth strategy now.

- Among the scenarios evaluated were different beneficiary characteristics, which showed that beneficiaries’ future incomes and tax situations can significantly affect the breakeven asset levels.

Roger Young, CFP®, is a vice president and senior financial planner with T. Rowe Price Associates, Inc. He is a subject matter expert in retirement and personal finance topics and helps develop and articulate the firm’s perspectives. Young earned a master’s in manufacturing and operations systems from Carnegie Mellon University, a master’s in operations research and statistics from the University of Maryland, and a BBA in accounting from Loyola University Maryland.

Disclosure: The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of T. Rowe Price. Information and opinions are derived from proprietary and nonproprietary sources deemed to be reliable; the accuracy of those sources is not guaranteed. This material does not constitute a distribution, offer, invitation, recommendation, or solicitation to sell or buy any securities; it does not constitute investment advice and should not be relied upon as such. Investors should seek independent legal and financial advice, including advice as to tax consequences, before making any investment decision.

NOTE: Please click or tap on any images in this article to open PDF versions.

JOIN THE DISCUSSION: Discuss this article with fellow FPA Members through FPA's Knowledge Circles.

FEEDBACK: If you have any questions or comments on this article, please contact the editor HERE.

Many people have two tax-advantaged options to save for retirement: Roth and pretax contributions. With Roth, an investor gets no tax break upon contribution, but qualified distributions in retirement are tax-free. Pretax (also referred to as traditional or tax-deferred) contributions reduce taxable income, but distributions are taxed as ordinary income.

Researchers agree that the Roth/pretax decision should largely be based on a person’s expected tax rates, at the time of contribution versus distribution. For some people, this is relatively straightforward. A young person in a low tax bracket may expect higher tax rates in the future and choose Roth. A mid-career worker in a high tax bracket probably benefits more from pretax contributions.

The decision is more difficult for late-career workers (for example, those over age 50) who have already amassed significant pretax assets. Their marginal tax rate may be at or near its peak. However, their tax rates may fluctuate over the course of retirement, making the analysis challenging. For example, the tax situation can change when the investor claims Social Security benefits, and again when required minimum distributions (RMDs) start. RMDs for affluent people, who don’t need all the money for retirement spending, may push them into a higher tax bracket.

In addition, someone with significant assets may reasonably expect to leave an inheritance, so the tax impact on beneficiaries should also be considered, if possible. The recent passage of the Setting Every Community Up for Retirement Enhancement (SECURE) Act of 2019, which generally requires full distribution of an inherited retirement account within 10 years, will likely result in higher taxes for many non-spouse beneficiaries of pretax assets. Inheriting Roth assets would alleviate this problem, but some workers are not eligible for Roth IRA contributions or haven’t had access to a retirement plan with a Roth option.

This study evaluates the Roth/pretax decision for late-career households at a variety of income and asset levels. It also considers factors such as filing status (married/single), current age, retirement age, Social Security claiming age, length of retirement, retirement contribution level, number of beneficiaries, and beneficiary income levels.

The study finds that asset levels are an important factor for late-career workers. Those who are solidly on track for retirement might benefit from switching to Roth contributions. By choosing Roth, lower taxes in retirement and for beneficiaries can outweigh higher working-year taxes in many cases. This can result in after-tax value to beneficiaries increasing by tens of thousands of dollars. Pretax contributions are often preferable for people with lower assets and those with income at certain levels relative to tax bracket boundaries. As a result of the SECURE Act, Roth contributions have become more favorable at significantly lower asset levels than before passage of the act.

Literature Review

Various approaches have been used to evaluate whether an individual should choose pretax (tax-deferred) or Roth retirement contributions. The calculation needs to account for the fact that if pretax and Roth contributions are the same size, the pretax approach results in more after-tax income to spend today. Some researchers assume that people will invest the tax savings resulting from a pretax contribution into a separate taxable account (Krishnan and Lawrence 2001). That approach requires additional assumptions about how the taxable account is invested, since different components of returns are taxed differently (Horan and Peterson 2001). Studies using the separate “side account” assumption tend to favor Roth contributions, at least in part due to the annual tax drag of the taxable account.

The alternative approach is to compare a Roth contribution with a larger pretax contribution, so the after-tax impact on a worker’s net pay is equivalent. This approach has the benefit of preventing any confounding of the Roth/pretax decision with assumptions about a taxable account (McQuarrie 2008). Under this assumption, the decision generally hinges on whether the person’s tax rate at the time of withdrawal is higher than upon contribution (which favors Roth) or lower (which favors pretax) (Crain and Austin 1997). Crain and Austin (1997) showed that if tax rates at contribution and withdrawal are the same, Roth and pretax contributions are mathematically equivalent. This study builds upon this fundamental approach. People might use a variety of approaches in practice, but they seem more likely to choose contribution amounts that achieve a budgeted net pay than to seek out a side account to invest tax savings.

Because statutory tax rates are not permanent and individuals’ tax circumstances can change, researchers have focused on the impact of tax rates upon withdrawal. Several researchers have found that individuals’ flexibility to take withdrawals (Adelman and Cross 2010) or convert assets to Roth accounts (Horan, Peterson, and McLeod 1997) when their tax rates are low tends to favor the pretax strategy. Roth investments, on the other hand, can mitigate the risk of higher statutory tax rates in the future. Brown, Cederburg, and O’Doherty (2017) emphasize this risk mitigation and propose a heuristic that gradually increases the portion of savings allocated to Roth accounts as an investor gets older.

There is widespread recognition that the decision is affected both by individual factors and various aspects of tax laws. McQuarrie (2008) emphasized that since withdrawals in retirement may be taxed in multiple brackets, it is important to consider the individual’s effective tax rate rather than the marginal tax rate. Adelman and Cross (2010) observed that RMDs and the taxation of Social Security can affect tax rates upon withdrawal. That concept was expanded upon by Geisler and Hulse (2018), particularly regarding strategies for withdrawals from different types of accounts. Reichenstein and Meyer (2020) advocated Roth conversions for many higher-income households before tax rates are scheduled to rise in 2026, a finding that is also relevant to other Roth/pretax decisions. Finally, because many people leave assets to heirs, Potts and Reichenstein (2015) noted the importance of beneficiaries’ tax rates in decisions about Roth and tax-deferred accounts.

This paper builds upon existing research in three ways. First, it focuses on the impact of assets already accumulated by workers relatively late in their career. While existing assets are sometimes discussed in examples (McQuarrie 2008; Young 2020) and Roth conversion analyses, they do not appear to have been identified or quantified in prior research as a key decision factor for current workers. Second, this study uses a detailed model to calculate breakeven asset levels that can be used as a decision tool by financial planners. Third, it evaluates results based on after-tax assets inherited by beneficiaries, including the significant impact of the SECURE Act. For many investors who are relatively well prepared for retirement, leaving an inheritance is likely, so the value to beneficiaries can be a more useful measurement than alternatives such as portfolio longevity or spending in retirement.

Methodology

This study was conducted using an Excel spreadsheet model. The model estimated a household’s income, Social Security benefits, taxes, spending, contributions, distributions (including RMDs), and asset values annually through working years and retirement. The ending asset values were then adjusted for the impact on beneficiaries’ income taxes, consistent with SECURE Act withdrawal requirements, to arrive at an after-tax inherited value. These calculations were performed separately for the Roth and pretax strategies. Importantly, those calculations assumed identical spending in both cases. Then, the after-tax inherited values for the strategies were compared.

The model was run for a variety of scenarios in two manners. First, the study calculated the dollar difference between strategies for a specific income level scenario, across different starting asset levels. That provided insight about the impact of asset level on the results for the two strategies. Second, the model was used to calculate breakeven asset levels (as a multiple of income) for different scenarios. Those breakeven levels can be used by financial planners and their clients to help determine the better strategy for a specific situation.

Description of the Baseline Scenario

The person (or each spouse) being analyzed was at least 50 years old, the age at which catch-up retirement contributions become available. The household started with a certain level of retirement assets (all tax-deferred). The household had access to a defined contribution plan(s), including a Roth account option. They aimed for contributions (including those from an employer) of at least 15 percent of income1 (pretax), subject to statutory limits. All income during working years—after income taxes, payroll taxes, and retirement contributions—is spent. Spending in retirement is a constant percentage of pre-retirement spending. In retirement, Social Security benefits are consistent with the household’s previous income level. Factoring in those benefits and taxes, spending needs are met first from the tax-deferred account, followed by any Roth assets.2 Any RMD income above what is needed for spending is invested in a taxable account.3 After the person’s (or couple’s) death(s), their beneficiary(ies) are subject to the 10-year distribution rule under the SECURE Act. In the cases being evaluated, assets and contributions are generally sufficient to sustain spending in retirement, assuming fixed investment returns.4

The decision the household faces is how to save (from now until retirement): continue pretax contributions or switch to Roth (in an amount that results in equivalent spendable income after taxes and savings).

Key assumptions for all scenarios:5

- Numbers are in today’s dollars (rounded)

- Real investment returns before taxes are fixed: 4 percent before retirement and 3 percent in retirement

- The household’s income keeps pace with inflation (i.e., no real wage change)

- Annual spending in retirement is 5 percent lower than before retirement

- Employer contributions are 3 percent of gross earnings

- Federal income taxes reflect the scheduled tax rate change in 2026; households use the standard deduction

- State income taxes are a flat 4 percent of income, excluding pretax contributions and Social Security benefits

Assumptions in the baseline scenario:

- Current age: 50

- Target pretax contribution percent (employee): 12 percent

- Non-spouse beneficiaries: two children of the individual/couple

- Gross income (before inherited retirement account distributions) for each beneficiary household is equal to the household income of the parent(s) during working years

- Retirement age: 65 (a common retirement age due to Medicare eligibility)

- Social Security claiming age: 65

- Length of retirement: 30 years

Illustration of the Problem

Suppose a dual-earner married couple, both age 50, has $225,000 of gross income. They plan to retire at 65 and expect a 30-year retirement. Their income will put them solidly in the 28 percent federal tax bracket (when tax rates revert to pre-2018 levels in 2026). After retirement contributions of 15 percent (including 3 percent from employers) and taxes, they spend $136,400 before retirement and 5 percent less ($129,500) in retirement. They will claim Social Security at 65 and receive $54,200 in annual benefits. At the time of the couple’s demise, their two beneficiaries will also be married, and each has $225,000 of gross household wage income with their respective spouses.

Lower accumulated assets. First, assume they have accumulated 3.4 times their income, or $765,000, in tax-deferred accounts for retirement. If they continue with pretax contributions, that grows to $2,054,000 by retirement. To meet their spending needs, they draw $102,100 per year from the tax-deferred account. They require less total income in retirement for multiple reasons: no payroll taxes, no need to save for retirement, and less tax on Social Security benefits than earned income. Therefore, they are in the 25 percent federal tax bracket throughout retirement. Their RMDs are never more than they need and don’t push them into a higher bracket. Assets at the time of their death are $129,000, and their beneficiaries end up with $88,000 after taxes.

If they switched to Roth contributions at age 50, they would still be in the 28 percent tax bracket while working and 25 percent in retirement. However, they would incur $123,100 more in income taxes before retirement than with pretax contributions. That difference, including compounded growth of the investments, outweighs the tax savings under Roth in retirement (and for the beneficiaries). With Roth contributions, the beneficiaries only get $42,000–$46,000 less than if the couple had stayed with pretax contributions. This is a classic example where pretax is preferable because the tax rate will be lower in retirement.

Higher accumulated assets. Now, assume the couple has accumulated 4.6 times their income, or $1,035,000 in tax-deferred accounts. Other assumptions, including their spending needs, remain the same. Starting with the situation where they continue pretax contributions, a higher asset level doesn’t affect their taxes before retirement at all. The couple pays a little more in taxes in retirement than with lower assets, due to some unneeded RMDs. But the big difference is for their two beneficiaries. They inherit $987,000 in tax-deferred assets and have to take full distribution of the account within 10 years. That significant extra taxable income pushes them from the 28 percent bracket to the 33 percent bracket each year. Including $229,000 of taxable assets (accumulated from unneeded RMDs), their after-tax inheritance is $880,000.

By switching to Roth contributions, their beneficiaries are better off. The couple nearly exhausts the tax-deferred assets during retirement, leaving tax-free Roth assets to the beneficiaries. The couple’s retirement tax rate is lower than the beneficiaries’, and the tax savings in this case outweigh the higher taxes with Roth before retirement. The beneficiaries inherit $915,000 after taxes, a $35,000 improvement.

This example illustrates the value of evaluating the full picture, including the impact on beneficiaries. Looking only at marginal tax rates before and during retirement would lead you to choose pretax contributions in both asset scenarios. That choice is good for the couple with more modest assets, but not for the one that is better positioned for retirement.

Impact of Asset Level on Results for Roth and Pretax Strategies

The only variable that changed in this example was the starting asset level. This suggests that asset level should be a key driver of the decision. The study calculated this impact using the baseline assumptions for several income levels.

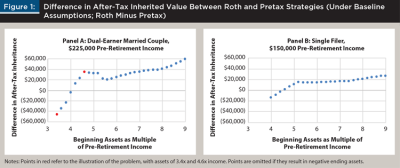

Figure 1 illustrates the impact of starting asset level on after-tax inheritance values for two examples. One is for a dual-earner married couple earning $225,000 (used in the example above), and the other is for a single filer earning $150,000. The dollar impact reflects the difference between Roth and pretax strategy results, so positive numbers indicate that Roth is preferable.

For either strategy (staying with pretax or switching to Roth), the inheritance value rises with beginning assets. In general, an increase in the assumed starting assets means that taxes during retirement and for beneficiaries become increasingly important relative to taxes during working years. That shift tends to favor Roth contributions under the baseline assumptions. As a result, the inheritance value rises faster for the Roth strategy than the pretax strategy, so the difference shown in Figure 1 generally has a positive slope.

In both panels, the after-tax inheritance difference is positive for most of the feasible asset levels, indicating that the Roth strategy is usually preferable. However, the graphs also tend to be steeper at low asset levels. That indicates that switching to Roth could be a significant mistake for people whose assets are near the borderline of running out in retirement. (In Panel B, asset multiples below 4.0 are not shown because they result in negative ending asset values.)

While the Figure 1 graphs have positive slopes on average, they do have points where the slope changes—or even turns negative. Those slope changes occur due to significant changes in the multigenerational household’s tax situation. An analysis of the results for different income levels indicates that there are several ways an increase in the assumed starting asset level can significantly affect the curve’s slope.

- Increases tax bracket in retirement (for one of the strategies)

- Increases tax bracket for beneficiaries (for one of the strategies)

- Results in tax-deferred assets left to beneficiaries under Roth strategy

- Causes unneeded RMDs (for one of the strategies)

The first two changes are straightforward. When greater assets push the household or beneficiaries into a higher bracket under a strategy, the curve bends in favor of the other strategy. However, those bracket shifts may not affect the graph as much as the other two types of changes.

Under the Roth strategy, a 50-year-old with relatively low starting assets will probably exhaust the tax-deferred account and end up with only Roth assets. As the starting asset assumption is increased, those incremental assets essentially go to the beneficiaries tax-free—until reaching the point where the household doesn’t exhaust the tax-deferred account. At that point, the curve bends sharply down (i.e., less favorable to the Roth strategy) around assets of 4.6x in Panel A. Then, when higher starting assets cause the Roth strategy to have unneeded RMDs, some of the tax burden shifts from beneficiary to retiree. That causes the curve to bend back up, around assets of 5.6x in Panel A.

The curve’s shape can look somewhat different across scenarios, depending on income, filing status, and beneficiary assumptions. But ultimately, in the cases studied, the benefit of the Roth strategy is always higher at the high end of starting asset assumptions than at the low end.

While understanding factors that can affect the curve’s shape may be helpful, a practicing financial planner should be more interested in information to help a client make decisions. In Figure 1, the curves cross zero at 4.05x income for Panel A and 4.58x for Panel B. Those represent the breakeven points for the scenarios—the asset level where either choice results in the same after-tax inheritance. People with assets above those levels (and whose situation fits the assumptions) should switch to Roth. Those breakeven points will be the focus of the remainder of this paper.

Breakeven Asset Levels

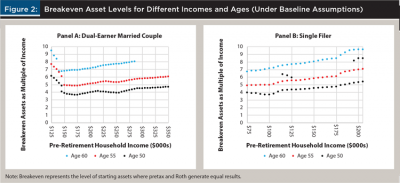

This study calculated breakeven points for a variety of income levels, for married couples and singles, and other parameters. Figure 2 summarizes the breakeven points using the baseline assumptions, but at three different starting ages. The range of income levels evaluated was $125,000 to $350,000 for married couples and $75,000 to $205,000 for single filers. Those ranges put the households at similar positions relative to tax bracket boundaries after tax rates are scheduled to revert in 2026. However, the range for single filers excludes income levels where the target contribution rate cannot be achieved due to statutory limits.6

For this baseline scenario, at many income levels, the breakeven asset levels for married couples are roughly 4x to 5x at age 50, 5x to 6x at age 55, and 6.5x to 8x at age 60. Common breakeven levels for singles are 4x to 6x at age 50, 5x to 7x at age 55, and 6.5x to 10x at age 60.7 People who fit the baseline profile and have higher asset levels benefit from switching to Roth contributions. Those starting with fewer assets should stick with pretax.

The breakeven asset levels are higher as the worker gets older, which makes intuitive sense. Someone who is 60 only has five years left to save before retiring at 65, so compared with a 50-year-old, it takes a higher level of starting assets to trigger tax challenges in retirement or for beneficiaries. However, the gaps aren’t so large that someone who still benefits from pretax contributions at age 50 couldn’t accumulate enough to merit changing that decision later.8

Effect of tax bracket boundaries. The breakeven points tend to rise gradually with income. However, there are income ranges where the breakeven points are significantly higher than for adjacent income levels.

For example, the breakeven point for married couples (Panel A) is significantly higher for income in the $125,000 to $145,000 range than at higher income levels. That income level puts the couple near the bottom of the 25 percent bracket (in 2026). That is a big jump from the 15 percent bracket, where the couple will be in retirement. Therefore, the tax deduction from pretax contributions is attractive until the asset level gets high enough that retiree and/or beneficiary taxes become more important factors.

After that initial high point, the graph in Panel A has more subtle waves as income increases. For a 50-year-old, the breakeven point starts rising again at income around $180,000 and $260,000. Both of those levels (after subtracting the standard deduction and exemptions) are near the bottom of tax brackets (28 percent and 33 percent, respectively). The waves are less pronounced for 55- and 60-year-olds, because the brackets affect fewer working years.

The graph in Panel B shows less sensitivity to brackets. However, the breakeven point does start increasing for a 50-year-old at $105,000, near the bottom of the 28 percent bracket.9

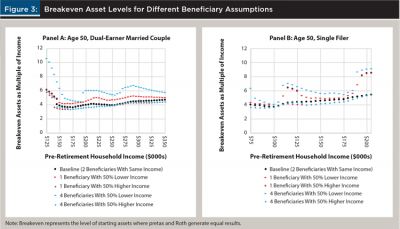

Impact of beneficiary characteristics. Up to this point, all of the analysis has reflected the baseline assumption that beneficiaries have the same income as the original household (during working years). Clearly, that does not describe all families. And because the objective is to optimize after-tax inheritance for those beneficiaries, those assumptions can have a major impact on the results. Therefore, the study also evaluated scenarios for different numbers of beneficiaries and with different income levels. Figure 3 illustrates the breakeven asset levels under four beneficiary combinations, in addition to the baseline.

These graphs show that having beneficiaries with lower income can significantly increase the breakeven point. That makes intuitive sense: the beneficiaries will have lower tax rates, so it is relatively more important to save taxes during the working years. Therefore, compared with the baseline, people at more asset levels will benefit from the pretax strategy.

However, having higher-income beneficiaries does not dramatically reduce the breakeven points. In some cases, the points are identical to the baseline cases. While the benefit of the Roth strategy can be significantly larger if there are high-income beneficiaries, that does not necessarily move the breakeven asset level much. For example, Figure 1 Panel A shows the breakeven point at assets of 4.05x, where the graph is very steep. Changing the assumptions to reflect one higher-income beneficiary moves the dollar values up, but due to the steepness, the breakeven point only decreases to 3.77x.

Changing the number of beneficiaries also has an impact. Spreading the inheritance over more beneficiaries reduces the likelihood of pushing them into higher tax brackets. The effect on the breakeven asset level is often meaningful for beneficiaries with lower incomes, but barely so for those with higher incomes.

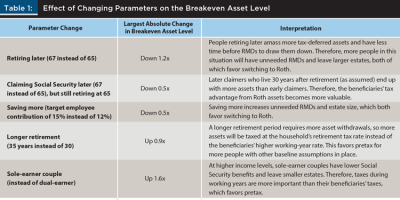

Impact of other factors. Factors other than income, asset levels, and beneficiary characteristics can also affect the decision. Table 1 shows how varying the parameters (one at a time, relative to the baseline) can affect the breakeven points across the income range studied. A higher breakeven point means that it takes a higher level of assets for Roth contributions to be preferable, so more people should choose pretax in that situation, compared with the baseline scenario. A lower breakeven point means more people should choose Roth.

Because of the importance of beneficiary assumptions, the study also evaluated these parameter changes for the case with four lower-income beneficiaries. It would seem possible that some assumption changes might have an opposite effect as a result of beneficiaries having a lower tax rate than the retiree. In general, however, the breakeven point changes were directionally the same with lower-income beneficiaries as for the baseline case. The impact was mixed with a longer retirement period, and claiming Social Security later had a noticeably smaller effect than shown in Table 1.

Impact of the SECURE Act

The SECURE Act was enacted in December 2019. Unless an exception applies, the act generally requires non-spouse beneficiaries of retirement accounts to withdraw all of the money within 10 years.10 Previously, beneficiaries could generally stretch those distributions over their expected lifetime. Financial planners have recognized that this change can significantly affect retirement and estate planning decisions.

Therefore, this study evaluated the Roth/pretax decision using both current rules and those in effect prior to the SECURE Act. For the pre-SECURE Act calculations, it assumes beneficiaries spread distributions evenly over a 25-year period. In addition, the pre-SECURE Act case uses the previous RMD starting age of 70½, which was changed, for those turning 70½ in 2020 or later, to 72 by the act.

A comparison of the pre-SECURE Act and post-SECURE Act breakeven asset levels is shown in Figure 4. The graphs show that those breakeven points were significantly higher before passage of the act. Under the baseline assumptions, those asset levels relative to income were higher by at least 4x income for dual-earner married couples, and at least 5x for single filers. Using other assumptions (as described in Table 1), the pre-SECURE Act breakeven asset levels were always higher, usually by at least 3x.

This finding highlights the importance of considering asset levels in 2020 and beyond. Many people who were making the right decision to stick with pretax contributions before may benefit from changing course now. Put another way, before the SECURE Act, you probably had to be a truly prodigious saver to benefit from Roth contributions late in your career. Now, just being relatively on track for retirement could make Roth the better choice.

The shape of the pre-SECURE Act graphs illustrates how the decision has changed. With a 25-year assumed withdrawal by beneficiaries, their tax rates were rarely a decisive issue. Rather, the graphs show much more dramatic differences related to tax brackets during working years.

Additional Considerations

In addition to assets above the breakeven levels, there are other reasons to consider Roth contributions that were not directly considered in this model.

- Tax diversification. Having some Roth assets offers a hedge against an increase in statutory rates.

- Flexibility. Spending can vary over time in retirement, and Roth assets can help you avoid higher tax rates in years with higher spending needs.

- Medicare premiums. Roth assets can also help you avoid crossing income levels that trigger higher premiums.

- Asset location. Having multiple account types allows you to choose investments best suited for each form of taxation. (This study assumed the same investment returns for all types of accounts.)

- Different assumptions. This study assumed that real spending remains constant during retirement, and there is evidence that it decreases for many people.11 In addition, the assumption that the taxable account funded by unneeded RMDs will not generate taxable income during retirement is favorable to the pretax strategy. Changing those assumptions would likely reduce the breakeven asset level.

There are also ways that people with large tax-deferred balances can reduce the negative tax consequences. People able to take advantage of them might consider staying with pretax contributions, particularly if they are close to the breakeven asset level.

- Roth conversions. While not considered directly in the study, conversions could be beneficial especially during low-tax early retirement years. However, there is a limit to how much someone can convert without bumping into a higher tax bracket. So, for people with assets well above the breakeven point, it is probably better to switch to Roth now—and also consider conversions early in retirement.

- Qualified charitable contributions. Charitable-minded retirees can use qualified charitable contributions from individual retirement accounts to satisfy RMDs they don’t need for spending without adding to taxable income.

- Beneficiary planning. Someone with multiple potential beneficiaries can consider their likely tax circumstances to inform which accounts to leave to each one. (This study assumed each beneficiary has the same income.)

Investors may also wonder whether to consider the current investment market environment. This factor could move the decision in either direction. If upcoming contributions will be invested in markets expected to have above-average growth, Roth contributions are theoretically more appealing. Someone concerned that the markets are overvalued could make pretax contributions now and consider Roth conversions at lower valuations after a market correction. The caveat is that it is difficult to predict the markets and even more difficult to coordinate that timing with changes in a person’s tax situation. Most people should probably focus more on the key factors identified in this study—income and asset level.

This study also has ramifications for younger workers. This analysis finds that late-career workers can benefit from switching to Roth, even if their tax bracket isn’t particularly low. But those workers would have been even better positioned if they had used Roth contributions earlier at lower tax rates. That was not necessarily feasible decades ago, but now employers increasingly offer Roth 401(k) contributions. The takeaway is that young workers with the ability to save aggressively should strongly consider Roth contributions.

Implications for Financial Planners

For workers late in their careers, who are relatively confident that they will not run out of money in retirement, switching to Roth contributions may improve outcomes for beneficiaries without sacrificing spending in retirement. This change in strategy is appropriate for people in many more situations following the passage of the SECURE Act.

This study provides planners with a practical tool to help identify the right course of action for clients: the breakeven asset levels. While planners often use goal-based software to build financial plans, that software may not be geared toward optimizing value for the next generation through decisions like the Roth/pretax choice. Although this paper does not cover every situation, it can be a starting point to prompt discussion. It may even demonstrate the value of financial conversations with clients’ children—ideally with guidance from the financial planner.

Endnotes

- This is a commonly recommended savings rate. For example, see T. Rowe Price. 2020. “Are My Retirement Savings on Track?” Available at www.troweprice.com/personal-investing/resources/insights/are-my-retirement-savings-on-track.html.

- While this is not necessarily the optimal withdrawal policy, it is a reasonable approach and allows for fair comparison of the Roth and pretax strategies. In addition, this assumed withdrawal policy means that adding Roth assets to the beginning balance would not affect the ultimate results (difference between pretax and Roth strategies).

- For simplicity, the taxable account funded by any unneeded RMDs is assumed to generate no taxable dividends, interest, or realized capital gains. (Examples could include some municipal bonds or non-dividend paying stocks.) Therefore, all growth is passed to beneficiaries tax-free due to the step-up in basis. This assumption is discussed further in the Additional Considerations section.

- Cases where the household runs out of money before the end of retirement are excluded from results shown.

- Additional assumptions for all scenarios:

- RMDs are based on the schedule as of January 1, 2020, including a starting age of 72.

- Social Security benefits are estimated using the ssa.gov Quick Calculator, adjusted for early or late claiming based on the appropriate full retirement age.

- Taxability thresholds for Social Security benefits continue to be constant, not adjusted for inflation.

- No investment returns are assumed after death.

- Both spouses are the same age. They also retire and die at the same age as each other.

- In dual-earner couples, the lower earner’s income is 75 percent of the higher earner’s (which primarily affects payroll taxes and Social Security benefits).

- Beneficiaries have the same tax filing status as the household. Tax calculations for beneficiaries do not reflect any pretax contributions they could make.

- Estate taxes and Medicare premiums are not considered. - An individual who wants to save more than statutory deferral limits allow might choose to supplement tax-advantaged savings with a taxable account. That significantly alters the nature of the problem and therefore is outside the scope of this study.

- Points are not shown for age 60 above an income of $285,000 because those points would result in negative ending balances under one or both strategies. This indicates that high-income 60-year-olds whose situation matches the baseline assumptions, are on track for retirement, and have no Roth assets would generally benefit from switching to Roth.

- Note, however, that the breakeven points identified in the study are specific to someone at a certain age in the current year (2020), due to the change in tax brackets after 2025. While the overall conclusions of the paper will remain applicable, planners and clients should not rely on exact data points after 2020.

- It is also worth noting that there can be multiple breakeven points. As noted in the discussion of Figure 1, the difference in value for the Roth and pretax strategies can change direction as beginning assets increase. If those occur at relatively small positive or negative values, the curve may cross zero at three breakeven points. Figures 2–4 show both the lowest and highest identified breakeven points.

- Exceptions apply, such as beneficiaries less than 10 years younger than the owner, minor children of the original owner, and disabled or chronically ill beneficiaries.

- See Sudipto Banerjee’s 2012 EBRI Issue Brief No. 368 titled, “Expenditure Patterns of Older Americans, 2001−2009.”

References

Adelman, Saul W., and Mark L. Cross. 2010. “Comparing a Traditional IRA and a Roth IRA: Theory versus Practice.” Risk Management and Insurance Review 13 (2): 265–277.

Brown, David C., Scott Cederburg, and Michael S. O’Doherty. 2017. “Tax Uncertainty and Retirement Savings Diversification.” Journal of Financial Economics 126 (3): 689–712.

Crain, Terry L., and Jeffrey R. Austin. 1997. “An Analysis of the Tradeoff Between Tax Deferred Earnings in IRAs and Preferential Capital Gains.” Financial Services Review 6 (4): 227–242.

Geisler, Greg, and David Hulse. 2018. “The Effects of Social Security Benefits and RMDs on Tax-Efficient Withdrawal Strategies.” Journal of Financial Planning 31 (2): 36–47.

Horan, Stephen M., and Jeffrey H. Peterson. 2001. “A Reexamination of Tax-deductible IRAs, Roth IRAs, and 401(k) Investments.” Financial Services Review 10 (1–4): 87–100.

Horan, Stephen M., Jeffrey H. Peterson, and Robert McLeod. 1997. “An Analysis of Nondeductible IRA Contributions and Roth IRA Conversions.” Financial Services Review 6 (4): 243–256.

Krishnan, V. Sivarama, and Shari Lawrence. 2001. “Analysis of Investment Choices for Retirement: A New Approach and Perspective.” Financial Services Review 10 (1–4): 75–86.

McQuarrie, Edward F. 2008. “Thinking About a Roth 401(k)? Think Again.” Journal of Financial Planning 21 (7): 38–48.

Potts, Tom L., and William Reichenstein. 2015. “Which Assets to Leave to Heirs and Related Issues.” Journal of Personal Finance 14 (1): 9–16.

Reichenstein, William, and William Meyer. 2020. “Using Roth Conversions to Add Value to Higher-Income Retirees’ Financial Portfolios.” Journal of Financial Planning 33 (2): 46–55.

Young, Roger. 2020. “Evaluating Roth and Pretax Retirement Savings Options.” T. Rowe Price Insights, available at www.troweprice.com/content/dam/iinvestor/planning-and-research/t-rowe-price-insights/retirement-and-planning/pdfs/evaluating-roth-and-pretax-retirement-savings-options.pdf.

Citation

Young, Roger. 2020. “The Roth/Pretax Decision in Late Career Years: The Increasing Importance of Accumulated Assets in Light of the SECURE Act.” Journal of Financial Planning 33 (12): 59–68.