Journal of Financial Planning: April 2012

It’s easy to overlook the role of housing in clients’ finances. Even though home equity can account for a large percentage of personal net worth, advisers and clients often view it as a use-asset, not an investment. Historically it has been a relatively unexciting asset subject to numerous popular maxims: “Pay off your mortgage before retirement,” “Don’t refinance unless rates fall 2 percent below your current rate,” and “Don’t borrow against your home equity unless you have no other options.”

Another truism was that the average homeowner could expect to see slow but steady price appreciation that roughly matched the inflation rate over time. The past few years undermined that notion: from July 2006 through November 2011, the S&P Case/Shiller 10- and 20-City Composite Home Price Indices have dropped 32.9 percent.1 Fortunately, there are a few rays of hope that the U.S. housing market is near a bottom. The National Association of Realtors reported that existing-home sales in December 2011 rose 5 percent versus November’s figures and were 3.6 percent higher than December 2010’s results. Some of the hardest-hit markets, including Miami, Atlanta, and Phoenix, had significant sales-activity rebounds in late 2011. Prices nationwide continue to fall but at a slower rate: the median existing-home price in December was $164,500, which was 2.5 percent below December 2010.2

Mortgages: Hold ’em or Fold ’em?

Mortgages matter. They’re a major expense for borrowers, and refinancing at a lower rate is an effective method to free up cash flow. One bright spot for borrowers in recent years has been the low level of mortgage rates. According to HSH.com, the average rate for a 30-year fixed mortgage in mid-2006 was 6.8 percent. By December 2011 that rate was 4.29 percent, and the average rate for one-year adjustable-rate mortgages was 3.24 percent.3 These rates are slightly higher than recent lows, but the Federal Reserve’s pledge to hold interest rates low for the next few years makes it unlikely that rates will move much higher soon.

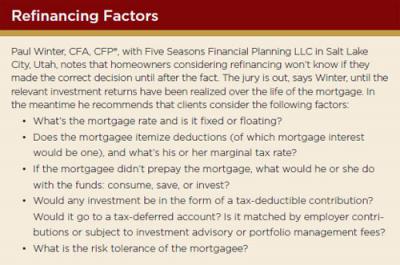

For qualified homeowners who are considering refinancing but haven’t already done so, the decision involves a straightforward cost-benefit comparison. Borrowers can use analytic software, including online calculators that ask for relevant data and assumptions to determine whether the refinancing will produce sufficient savings to justify the transaction’s expenses. (See the sidebar for one adviser’s thoughts on the key refinancing variables.)

Decisions on accelerating mortgage repayment are more complex, however. The prepayment analysis requires assumptions about tax rates, the return that can be earned on the home, and the funds that would be used for the prepayment—in other words, the opportunity cost of prepayment, and the client’s investment alternatives and overall asset allocation. Another consideration: although prepayment generates guaranteed savings of the after-tax interest expense, it also builds wealth in an illiquid asset, and it can affect a taxpayer’s ability to itemize other deductions.

Michael Kitces, CFP®, CLU, ChFC, RHU, REBC, presents an interesting analysis and commentary about the use of mortgage debt in his Nerd’s Eye View blog entry “Why Is It Risky to Buy Stocks on Margin but Prudent to Buy Them ‘on Mortgage’?”4 Kitces points out that taking out a margin loan to leverage a retirement portfolio for potentially higher growth “would most assuredly be deemed imprudent and excessively risky.” Nonetheless, he notes, advisers often recommend that clients invest available cash flow in their portfolios instead of prepaying their mortgage. It’s a form of homegrown risk arbitrage, and he questions the logic: “There’s just one problem: from the perspective of the client’s balance sheet, buying stocks on margin and buying stocks ‘on mortgage’ represent the same risk and the same leverage, even though our advice differs. Are we giving advice that contradicts ourselves?”

Among the advisers interviewed for this article, however, most were not currently in favor of prepayment. Marc Freedman, CFP®, president of Freedman Financial in Peabody, Massachusetts, generally counsels clients that paying down a mortgage isn’t an optimal solution with rates so low.

“Unless you’re planning on turning your house into cash and moving somewhere else, the necessity to pay down debt in the interest rate environment that we’re in today may not be all that appropriate,” Freedman adds. “What you’re doing is you’re locking more of your wealth in your house, and it’s probably wealth that you will never, ever tap in your lifetime. I often say to clients, you know you can’t pull a window out of your house and go down to the bank and ask for money.”

But Freedman also cites the emotional security some clients derive from having no mortgage as an important factor. Clients deciding to prepay have the attitude that “no one is going to be able to kick me out of my house because I own it,” he says. “I do see this happen more with women than with men. It’s a defensive strategy, and it’s not one that you completely dismiss—it’s an appropriate emotion to consider.”

Christopher Cordaro, CFA, CFP®, wealth manager with RegentAtlantic Capital LLC in Morristown, New Jersey, says he tells clients there are two answers to the “Should I pay off the house?” question. He calls the first response his MBA finance final-exam answer: If the clients’ after-tax cost of mortgage debt is lower than the potential after-tax return in their portfolio then from a financial sense they shouldn’t pay off the mortgage.

The second answer recognizes some clients’ desire to be debt-free when they retire. To address that issue, Cordaro illustrates the financial cost of prepayment. He cites an example in which the clients’ mortgage balance is $500,000. The analysis assumes a positive spread of 3 percent between the after-tax mortgage cost and the projected after-tax return from investing. “We can then start quantifying it for them and say, okay, you’ll feel more secure in retirement with this [mortgage payoff], but realize that it’s costing you about $15,000 a year,” he says. “You can make the decision of whether that’s right or wrong. If it’s going to make you feel a lot better then maybe that’s the right answer.”

Occasionally it makes economic sense to increase mortgage debt. One of Cordaro’s retired clients was due for a $200,000 portfolio distribution in early 2009 when the markets were substantially lower. Instead of withdrawing funds when his investments’ values were depressed, the client decided to cover his living expenses with a home equity line of credit. His portfolio recovered by mid-2010, at which time he took a distribution and paid off the equity line. The strategy worked well, says Cordaro: the client paid a modest interest rate on the equity line balance, but the retained $200,000 in portfolio assets recovered by 35 percent, or $70,000, over the same period.

All in the Family

Even with prices depressed nationwide, homes in some markets have held up well and remain expensive. According to Fiserv Case-Shiller, single-family median housing prices at the peak were four times the median income; by late 2011 the ratio had dropped to 2.7 times. In some cities, though, the ratio has held up—in Los Angeles (5.9), San Francisco (4.9), and New York (4.6), for instance—making it harder for many buyers to find an affordable home.5

If clients have adult children who live in high-priced markets and are having difficulty with home financing, Kristi Mathisen, J.D., CPA/PFS, managing director of tax and financial planning for Laird Norton Tyee in Seattle, Washington, suggests they consider setting up what she calls the “Bank of Mom.” The parents agree to lend the adult child the money for the purchase and base the interest rate on the prevailing applicable federal rate (AFR) for the appropriate loan term. Alternatively, the parents could provide the funds for a private refinance in which the children pay off their current, higher-rate mortgage. Provided the parents charge at least the prevailing AFR for the loan’s term, the transaction avoids being treated as a gift. It’s a good deal for the children: Mathisen notes that the highest rate on mid-term AFRs (for loans of three to nine years) has been less than 2.8 percent since 2009. (The February 2012 mid-term annual AFR is 1.12 percent, and 2.58 percent for the long term.6)

Mathisen warns clients that there are potential drawbacks to these loans, though. “If you can’t afford to lose that money then don’t lend it,” she cautions them. “It’s even more true, I think, with children—you need to be prepared for that.”

Mathisen advises parents document the loan properly and record a lien. They also should require that the children make the required payments with interest, even if the parents decide to gift back the payments later. “I think the kids should get used to writing a check and paying the mortgage and figuring out how they’re going to pay the mortgage,” she says. “If mom and dad choose to give the money back, more power to them, [but] I actually like the formalities of an exchange of checks.”

Rethinking Reverse Mortgages

Most of the advisers interviewed for this article view the home as a use-asset, not an investment. Consequently, they believe that short- and medium-term changes in home values don’t matter much to the clients’ financial health. They also note that older clients often hope to leave their homes, preferably mortgage-free, to their children—so there’s little reason to worry about current market conditions. Depressed prices affected only those clients hoping to refinance or sell in the short term.

But several trends indicate that it may be time to reconsider home equity’s role in generating retirement income. First, the number of workers receiving pensions continues to fall. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, in 2010, only 20 percent of private-industry employees had access to traditional defined-benefit plans, making them more reliant on personal savings such as 401(k) plan accounts.7 Second, low interest rates and relatively low dividend yields reduce investment income. Retirees who can’t earn sufficient income from their savings could incur unacceptably rapid principal depletion as a result. Third, longer life spans and the increasing cost of health care are putting additional, often unanticipated strains on retirees’ budgets.

One option for cash-strapped retiree homeowners is to downsize to a smaller home, but is that a viable solution? Rick Kahler, CFP®, ChFC, president of Kahler Financial Group in Rapid City, South Dakota, says that downsizing works better in theory than practice. Kahler, who has 30 years’ experience in both real estate and financial planning, recalls seeing just two instances of successful downsizing. The problem, he says, is that the homeowner usually buys a house in a better location and negates the potential savings, so Kahler discounts downsizing in his work with clients.

Evidence of the strain on retirees’ budgets is their growing presence in the workforce. A recent Wall Street Journal article cited several revealing statistics: “Now, 7.3 percent of the oldest Americans [75 and older] have jobs, up from 5.3 percent a decade ago and the highest level since 1966, according to the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College. By 2018, the government estimates about 10 percent of people 75 or older—about two million Americans—will be working or seeking work.”8

Although some seniors need additional income, as a cohort they have significant value in their homes. The National Reverse Mortgage Lenders Association (NRMLA) in Washington, D.C., reports that seniors had $3.19 trillion in home equity available in the third quarter of 2011.9 It’s illiquid wealth; however, financial advisers frequently cite reverse mortgages’ high costs as detrimental to potential borrowers.

John Sestina, CFP®, ChFC, president of John E. Sestina and Company in Columbus, Ohio, cites an example of a reverse mortgage borrower who qualifies for a 4.2 percent loan rate. “By the time they go through the FHA’s HECM (the Federal Housing Administration’s Home Equity Conversion Mortgage program), the rate goes up to about 6.2 percent. Then they’ve got the monthly service fee of about $30 and the upfront set-aside fee, which is about $4,000. There’s an upfront loan origination fee of about $6,000. There’s another upfront fee for mortgage insurance of about $9,000. Then there are other closing costs, of course, of about $3,900. So you’re looking at maybe another $20,000 that is added to the cost. And, of course, the cost is added to the mortgage amount, and the interest that is calculated during the term of this program is being paid on this additional cost.”

Sestina raises valid objections, and his comments are representative of the arguments against reverse mortgages, but several developments could increase reverse mortgages’ acceptance among advisers. First, the FHA introduced the HECM Saver reverse mortgage in September 2010. The product offers lower upfront costs coupled with lower lending limits. A second development is ongoing academic research into reverse mortgages’ potential role in managing retirement income. A February 2012 Journal of Financial Planning article by Barry Sacks and Stephen Sacks, “Retirement Income Withdrawals: Reversing the Conventional Wisdom,” investigated several strategies using reverse mortgage credit lines to supplement withdrawals from retirees’ savings. Their research found that using the credit line during retirement (with their proposed active borrowing strategies) instead of treating home equity as an asset of last resort substantially improved cash-flow survival probabilities. This approach also proved likely to result in a higher residual net worth for the client after 30 years.

Other researchers are also finding benefits from reverse mortgages. John Salter, Ph.D., CFP®, with Evensky & Katz Wealth Management in Lubbock, Texas, is an assistant professor in the division of personal financial planning at Texas Tech University. Salter and one of his Ph.D. students have been analyzing integrating reverse mortgages into clients’ cash-reserve strategies. Their research indicates that having reverse mortgage credit available could reduce clients’ need for cash reserves and subsequently lower the opportunity costs of holding large amounts of liquid reserves.

Reverse mortgage proponents argue that the products can address multiple needs in the right circumstances. Jonathan Neal is senior partner with Capital Consulting Group in Atlanta, Georgia, and author of Reverse Mortgages: What Every Financial Advisor Should Know (National Underwriter Company, 2009). He believes reverse mortgages can give clients tax-planning flexibility because the loan proceeds are not taxed as income. In other cases, the mortgages can improve clients’ cash flows. He gives the example of a 78-year-old woman who was living in a retirement community and carrying a $150,000 mortgage with a monthly cost between $1,100 and $1,200. Using a reverse mortgage to pay off the traditional mortgage made sense for her, says Neal: “We did the reverse mortgage, she gets a couple dollars extra in her pocket, but she no longer has to pay that mortgage. You didn’t do anything from your point as far as generating money as the planner but you did something very good for your client. You gave her a $1,100 to $1,200 raise without changing her circumstances.”

Selling an Option

As Freedman observed, homeowners can’t sell parts of their home to raise cash, but the option to sell a portion of a home’s potential future appreciation is emerging. NestWorth Inc. and FirstREX Agreement Corp., both located in San Francisco, California, are among the participants in this market.10 FirstREX provides borrowers a lump-sum payment, and NestWorth offers initial and monthly payments. The purchases are funded by real estate investors whose profit is determined by the home’s price appreciation over the life of the agreement.

In theory, at least, private parties could provide older homeowners the funds for reverse mortgages and partial sales of future appreciation. For example, wealthy adult children could create a line of credit or make a lump-sum payment to their parents at more favorable terms than commercial lenders and investors. The sons and daughters would have to evaluate the mortgage’s or equity investment’s role in their investment portfolios, but intra-family transactions could benefit all parties.

Despite the prolonged slump in home prices, decisions on housing finance play an important role in many clients’ plans. Rules on housing finance decisions that worked in the past are becoming outdated, and advisers and clients can benefit from reconsidering their assumptions.

Ed McCarthy, CFP®, is freelance financial writer in Pascoag, Rhode Island.

Endnotes

- “Home Prices Continued to Decline in November 2011.” S&P Indices news release: January 31, 2012.

- “December Existing-Home Sales Show Uptrend.” National Association of Realtors news release: January 20, 2012.

- Rates quoted from HSH.com on January 30, 2012.

- Kitces, Michael. 2011. “Why Is It Risky to Buy Stocks on Margin but Prudent to Buy Them ‘on Mortgage’?” Nerd’s Eye View blog (October 24). www.kitces.com.

- Bernard, Tara Siegel. 2011. “A Dream of Homeownership, Still Beyond Reach.” New York Times (November 8).

- February 2012 AFRs: http://www.irs.gov/pub/.

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2010. “Retirement Benefits: Access, Participation, and Take-Up Rates Data Table.” Employee Benefits Survey (March). www.bls.gov/ncs/ebs/benefits/2010/ownership/private/table02a.htm.

- Greene, Kelly, and Ann Tergesen. 2012. “More Elderly Find They Can’t Afford Not to Work.” Wall Street Journal (January 21).

- “Senior Home Equity Increases by $46

Billion in Q3 2011.” National Reverse Mortgage Lenders Association news release: Januay 18, 2012. - Additional information is available at www.nestworthinc.com and www.1rex.com.