Journal of Financial Planning: November 2022

Executive Summary

- Addressing the issue of “wealth gap,” particularly among people of color and other disadvantaged groups, has been one of the primary focuses of many politicians, activists, and industry leaders as well as financial services professionals. Small business ownership is an established method for individuals of varying backgrounds to amass significant wealth.

- In this paper, we aim to assist financial advisers in understanding the challenging landscape for African American business (AAB) owners and utilizing this knowledge to help their clients improve their business outcomes by studying the role personal credit has on access to credit.

- Using the 2019 data from the Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF), we first show that AAB owners have worse credit profiles than business owners of other ethnic groups. We also document a positive association between better personal credit and the use of personal financial planners for AAB owners, with the expectation that this will improve access to capital and therefore improve business outcomes.

- We also provide guidance for financial advisers to improve their efficacy in assisting African American business (AAB) owners in improving business outcomes, such as utilizing decentralized finance as a means for obtaining capital and mitigating the discrimination risk inherent in obtaining credit from traditional banking institutions.

Leon Chen, Ph.D., FRM, is a professor of finance at Minnesota State University Mankato. He has published in various academic journals such as Journal of Risk and Insurance, North American Actuarial Journal, and Journal of Investing in the past 10 years.

Sophia Duffy, J.D., CPA, is an associate professor of business planning and assistant vice president of curriculum quality at the American College of Financial Services. She teaches classes in business and estate planning at the undergraduate and graduate levels.

Daniel Hiebert, Ph.D., CFP®, is an assistant professor of finance at Minnesota State University Mankato. He has more than 26 years of financial service industry experience, and currently also serves as the director of the financial planning program.

JOIN THE DISCUSSION: Discuss this article with fellow FPA Members through FPA's Knowledge Circles.

FEEDBACK: If you have any questions or comments on this article, please contact the editor HERE.

NOTE: Click on any images below for PDF versions

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, approximately one out of 10 adults is self-employed, and small businesses represent 40 percent of the wealth in the United States. Small business owners tend to be older, married, educated White males who possess higher asset levels compared to employees/salaried workers (Fairlie 1999; Fairlie 2010). Recent political and social discourse has centered on the widening wealth gap, or the economic disparity affecting communities of color and other disadvantaged groups. One way to close the wealth gap is to support the success of minority business owners.

The evidence is clear that supporting minority-owned businesses benefits both individual business owners and the broader U.S. economy. Fairlie (2010) found that minority-owned businesses employ millions of Americans, generate billions in revenues each year, and are growing at a faster rate than White-owned businesses, with African American-owned businesses (AABs) growing at the fastest rate. In the first four years of operation, minority-owned businesses created 60 percent more jobs, compared to non-minority owned businesses, with similar pay rates. From a qualitative perspective, supporting minority-owned businesses leads to the infusion of new and innovative ideas from diverse cultural and social backgrounds.

Unfortunately, the demographic characteristics for business owners and financial outcomes for AABs paint a rather bleak picture. Fairlie (2010) and Fairlie and Robb (2007) found that African Americans are only one-third as likely to enter self-employment compared to White Americans, and twice as likely to exit self-employment. As a percentage of business owners per workforce, 12 percent of White workers are business owners, and about 4 percent of African American workers are business owners, a percentage that has remained stagnant over the past 90 years (Fairlie and Robb 2007). A recent article in the Wall Street Journal noted that AABs represent only about 2 percent of U.S. companies. In addition, AABs fare poorly compared to White-owned businesses, with only half as many AABs earning at least $100,000, and a 4 percent higher probability of business closure (Fairlie and Robb 2007).

Fairlie (2010) found that lack of access to capital for the business is the most critical factor contributing to these business failures, stemming from significantly higher denial rates or approval for lower funding amounts compared to White business owners seeking credit. Banks, especially small community banks, rely heavily on personal finances, primarily focusing on credit scores when evaluating loan applications by small businesses. Additionally, banks may also consider other personal finance categories, such as personal wealth accumulation, insurance, and cash flow (Breen, Calvert, and Oliver 1995). Breen, Calvert, and Oliver (1995) also found that personal financial planning can have a positive influence on alleviating some of the obstacles that could perhaps cause undercapitalization or otherwise contribute to poorer business outcomes. One financial planning outcome in particular would be improving credit profiles, which have been shown to be a primary source of creditworthiness.

In this paper, we extend the previous study and examine whether working with financial planners (advisers) can help African American business (AAB) owners strengthen business and personal credit profiles, which can help improve their overall financial security and business outcomes. The value of utilizing a financial planner (adviser) can be derived from human capital theory, which recognizes that increased productivity can be attained through the improved education and skills training (Becker 1962). In our empirical model, we estimate the probability of “bad credit”1 of business owners, using factors such as race, age group, net worth, household and business income, and the interaction terms to capture the differences among African American business owners based on their use of a financial planner, gender, and education level. We show that although AAB owners are more likely to have bad credit profiles than business owners of other races, those who work with financial planners are less likely to have bad credit than those who don’t. Our results suggest that AAB owners can improve their credit profile by utilizing an expert financial adviser as their agent to provide guidance toward increasing creditworthiness. By understanding that lack of capital as a specific risk to AAB owners, financial planners (advisers) can provide targeted, effective advice, which can help improve client credit profiles and potentially lead to better access to capital and improved business outcomes for AAB owners.

Literature Review

African Americans have lower entry rates into self-employment and higher exit rates. Several studies show that lower education levels, personal asset and startup capital levels, and instances of having a self-employed parent all correlate to the lower entry / higher exit rates (Fairlie 1999). Although all of these factors contribute to the disparity between African American and White business owners at varying levels, Fairlie (1999) and Fairlie and Robb (2007) found that access to capital is the single most important factor contributing to poorer business outcomes for African American-owned businesses (AABs), with the lack of access to credit being two to three times more likely as the cause of business closure for AAB owners, compared to White business owners. However, AAB owners seeking credit from banking institutions face discrimination when obtaining credit from banks, experiencing higher denial rates and lower approved-funding amounts compared to White business owners.

The Linkage Between Personal Wealth and Access to Credit

Greater personal wealth, including amounts inherited, increase available capital and result in more positive outcomes for the business. Most small business loans from commercial banks require personal guarantees by the owners. An owner with greater wealth is less likely to be denied because the bank secures the loan with the owner’s personal assets, including home value (Fairlie 2010). AAB owners are only slightly more likely to rely on credit cards for startup funds than are White business owners.

However, the median level of net worth for Black households is about one-tenth compared to White households (Fairlie and Robb 2007). Estimates from the U.S. Census Bureau indicate that half of all African American families have less than $5,446 in wealth. Wealth levels among White families are 11 to 16 times higher. While three-quarters of White people own a home, less than half of African Americans are homeowners (Fairlie 2010). In addition, the net home value for African American homeowners averages $40,000, while the average value for White-owned homes is $79,200. Due to the decreased access to capital, African Americans are more likely to start businesses with no capital or insufficient capital, which leads to higher likelihood of business failure.

Credit Access and Discrimination

Unfortunately, discrimination plays a major role in the credit disparity. Several studies show that loans requested by AAB owners are denied more often, and approved loan amounts are lower than approved amounts for White business owners, even after controlling for personal wealth, education, and industry. The Federal Reserve Board found that AAB owners applying for credit experienced denial rates two to three times higher than White business owners, and only 47 percent were approved for the full amount, compared to 76 percent of White business owners. Similar findings were confirmed by Fairlie (2010). Once the loan is approved, the interest rates are not significantly higher for African Americans (Cavazullo, Cavazullo, and Wolken 2002). The Federal Reserve Board report noted that this credit disparity only exists for commercial banks and is not found when examining other lending institutions such as credit unions. In addition, lenders often use personal credit scoring in small business lending because there is more quantitative information available about personal credit (as opposed to small business information, which is often private), and many banks consider the business as an extension of the person, presuming that the good personal debt management habits will carry forward to the business. For Small Business Association (SBA) loans, high business credit scores are required as well.

While credit scores are a composite of several factors, the Federal Reserve Board noted that certain factors that are included in the credit scoring model, such as homeownership, negatively impact African American applicants to a greater extent due to systematic, historical, and institutional biases. African Americans have lower rates of homeownership, due in part to the historical practice of “redlining,” which prevented individuals in majority-Black neighborhoods from being approved for mortgages (Mitchell and Franco 2018). Though redlining has been outlawed, the effects continue to impact communities of color.

Fear of Applying

One significant factor in the credit disparity is the “fear of applying” that prevails among AAB owners (Fairlie 2010). African Americans are three times less likely to apply for credit due to fear of rejection or discrimination. In fact, the fear of rejection was the top reason for avoiding applying for a loan, cited by 59 percent of AAB owners compared to 47 percent of White owners. Rooted in this fear is the belief that an imperfect credit score or credit history will lead to rejection (Cavalluzo, Cavalluzo, and Wolken 2002) and in observed differences in treatment during the loan request process. The Wall Street Journal reported that AAB owners were less likely to be offered assistance in completing the loan application and/or offered a business card by the loan officer. Rather, the applicants were asked more often for financial statements and information about their business. This treatment only further discourages AAB owners from applying for credit. Of note, Howell et al. (2022) found that application rates among African Americans using automated lending platforms are higher than in-person applications. The higher application rates may signify that the fear of bias and discrimination is reduced in applicants by the removal of human interaction in the lending process.

Other Sources of Capital—Venture Funding, Professional Networks, Community Banks

Capital acquisition through other routes tells a similar tale. Fairlie (2010) found that minority businesses have less success securing funds through venture capitalists and angel investors, and minority business owners often have fewer network connections in these organizations. Private equity funds that specifically focus on minority businesses represent only 3.6 percent of all angel investors, even though these funds produce large returns. In addition, the overall equity secured by minority businesses is less than half that of White-owned businesses.

Another source of capital is community banks, defined as banks that serve their local communities. They stand out as one of the avenues small business owners often pursue to obtain credit. Community bank loans represent 36 percent of small business loans, while only representing 15 percent of total industry loans. Community banks differ from larger, commercial banks because they focus on relationship building with small business owners and the surrounding community, while larger banks focus on less human interaction and more automated processes. Furthermore, many community banks are part of the Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFI) Program from the U.S. Treasury that actively addresses the issue of lack of capital access among low-income and underserved people and communities.2 Community banks in such programs receive financial and technical assistance from the federal government to support their abilities to meet the needs of the communities they serve.

Interestingly, while Ergungor (2010) found that the presence of a physical branch within a community led to higher approval rates for loans, approval rates for African American loan applicants increased when automated lending platforms were utilized by eliminating or reducing human bias from the application decision process (Howell et al. 2022).

Using Financial Advice to Improve Outcomes for African American Business Owners

Financial planners can play an important role in helping AAB owners improve their credit profiles by helping to increase their chances of obtaining business bank loans. The guiding assumption in financial planning and counseling is that those who seek the help of a financial professional to build and implement a plan to achieve their financial goals will ultimately be successful (Grable and Joo 1999). And although the topic is succession planning, Chrisman, Chua, Sharma, and Yoder (2009) concluded that planning is best done by working with a financial professional who understands the personal goals and objectives of business owners. Jurinski, Down, and Kolay (2016) also suggested business owner clients seek out financial planners who understand both the personal needs of the individual and the entrepreneurial spirit that drives them. Thus, if the goal of AAB owners is to improve their credit profile to increase their chances of obtaining bank loans, working with a financial planning professional appears to be a good decision.

Specifically, personal financial planning provides attributes and antecedents to building good credit profiles. Mittra, Sahu, and Starn (2012) highlighted the importance of good credit in financial planning, and the difficulty consumers can face if it is negative. The authors outlined ways that financial planners can assist clients with debt management and debt reduction strategies to improve their credit profile. And although the CFP Board’s Financial Planning Competency Handbook (CFP Board 2015) does not mention specifically advice regarding effectively managing credit profiles, it does indicate that effective debt management is integral to the financial planning process. It states that prudently leveraging debt can be an effective way to accomplish personal financial goals such as pursuing entrepreneurial ventures. Perhaps an outcome from this study could provide a catalyst for planners to also include specific planning regarding improving credit profiles.

An important step for financial planners to help improve clients’ credit profiles is to first understand what the key factors are in the credit evaluating process. According to consumer credit reporting agency Equifax, personal credit is evaluated according to the following factors: the number of accounts, the types of accounts, used credit versus available credit, the length of credit history, and payment history. The types of credit scoring factors used by lenders may vary based on the borrower’s industry. Lenders may also use a blended credit score from the three major credit bureaus. They may also weight each factor differently according to certain proprietary factors. As noted in the section “Credit Access and Discrimination,” it is unfortunate that credit scores can and do reflect a history of societal biases and discrimination. However, financial advice regarding budgeting to manage cash flow, an adequate emergency fund, having personal insurance, and saving and investing regularly can help AAB owners improve their individual credit scores. These are core elements of financial planning according to the CFP Board’s Financial Planning Standards Competency Handbook (CFP Board 2015).

According to Jurinski, Down, and Kolay (2016), current financial position might be the most critical area of financial planning for business owners, as many owners use personal savings to get the business started. As the authors pointed out, many business startups in the initial stages struggle in the first few years to build consistent revenue and profits. If the owner does not have enough income generated from the business to fund their business and personal needs, the result could create stress and anxiety, and lead to closing the business prematurely. Having adequate cash reserves (vastly exceeding the commonly recommended three to six months) would supply the resources to keep their personal expenses paid, thus alienating stress and anxiety. Cash flow can be improved by reducing or eliminating debt service pressures by limiting debt to reasonable levels (or eliminating all debt), ensuring adequate amounts of long-term assets to provide collateral, and reducing the anxiety of postponing savings until the business becomes financially stable. Fan and White (2003) found that entrepreneurs with higher personal debt levels chose not to start a business, with many finding borrowing obstacles from banks due to the higher debt levels.

Proper risk management can also help improve credit profiles by transferring the financial risk to the insurance company and not forcing the AAB owners to use debt to finance risk exposures. Risk management refers to finding methods to mitigate risk exposures. Business owners face more risk exposures than other individuals. Jurinski, Down, and Kolay (2016) also referred to personal contingency planning for business owners, which may be more applicable than business exposures because personal risk exposures are detrimental to the individual and to the business as well. Not having adequate health insurance coverages such as disability and health insurance could force an AAB owner to use debt in health and disability situations. Disability insurance coverage pays in the event an individual is not able to earn income due to illness or accident. Not having adequate disability insurance can have negative effects for the business, as many business owners play significant leadership and management roles in the business (Jurinski, Down, and Kolay 2016). Their absence through disability could jeopardize the business. Inadequate (or lack of) health insurance can also force AAB owners into situations where they would need to use debt to finance medical bills, and medical costs are a significant factor in personal bankruptcies.

Investment planning also can play a part in improving credit profiles. Lenders appear to factor business owners’ personal wealth into their borrowing decision-making (Breen, Calvert, and Oliver 1995). This is in part to determine collateral for the loan, but also to demonstrate to the lenders good financial habits such as saving and investing. Proper tax planning can help improve an AAB owner’s credit profile. Jurinski, Down, and Kolay (2016) claimed that many small businesses fail in part because of poor tax planning. This could mean that the AAB owners may be paying more in taxes and not using these dollars for debt management or improving their personal credit profile. Financial planners can work with the AAB owner’s CPA or EA to find deductions and credits to lower taxes and to improve cash flow. In addition, proper estate planning can play a part in access to capital as well, if not improving credit profiles. According to Jurinski, Down, and Kolay (2016), business owners often do an excellent job running the business; however, they do a poor job planning for the effects of their death on the business and fail to engage in business succession and estate planning. If succession planning is not done (or is incomplete), lenders are less likely to approve capital for the business, due to the risk of loss if the business owner were to die. In particular, many lenders may require the owners have buy–sell agreements and key person insurance before they agree to lend or may lend lower amounts.

A critical issue in this discussion is the lower rates of financial advice sought by African Americans, especially for business owners. Research by White and Heckman (2016) concluded that the low rates of use of financial planners by African Americans could be a contributing factor in the undercapitalization of AABs.3 They cited the following reasons for not using financial advice: (a) lack of financial knowledge, (b) lower risk tolerance,4 (c) cultural issues, which may lead to distrust, and (d) lower asset and wealth levels, which do not align with planners who have an asset-based fee model (Winchester and Huston 2013). The last factor could be the most significant. Using data from the 2015 Survey of Consumer Finances, White and Heckman (2016) pointed out the startling contrast in income and wealth between White and non-White people, resulting in a hesitancy to engage in a fee-based service.

Empirical Analysis

Sample, Data, and Method

In this section, we use the most recent 2019 Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF) public database published by the Federal Reserve to study whether there is an association between the use of financial planners by AAB owners and their credit profile. SCF is a triennial cross-sectional survey of U.S. households that includes information on their demographic characteristics, balance sheets, income, pension, etc., and is sponsored by the Federal Reserve Board in cooperation with the Department of the Treasury, and no other study for the country collects comparable information.5

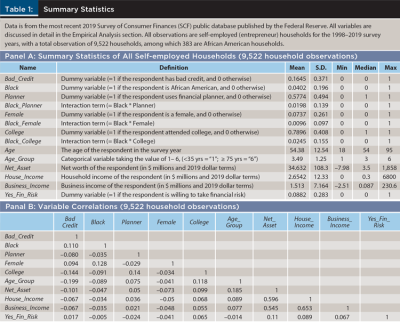

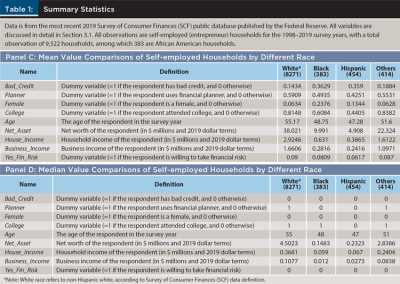

Since our study focuses on African American (Black) entrepreneurs and the effect of the use of financial planners, we extract the data of the “self-employed” households from the SCF database for all survey years from 1998 to 2019.6 The publicly available SCF database has five implicates for each household, and this multiple imputation (MI) problem may cause an over-estimation of statistical significance and model reliability when researchers estimate regression models, if all five implicates are used for each household. As Kennickell (1998) pointed out, due to the high level of missing data, nonresponse rates, and disclosure limitation, this MI method provides more informative data overall than anything that could be constructed with the data available to the public. Therefore, we calculate the average of all variables for each household across all five implicates, as recommended by the Federal Reserve website.7 Our final sample includes a total of 9,522 households (observations) during survey years of 1998–2019, and among them 383 are African American families. All estimates in our data sample are inflation-adjusted to 2019 dollars.

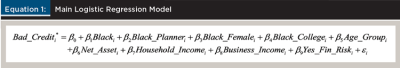

We then use the logistic regression models to estimate the probability of “bad credit,” where Bad_Credit is a dummy variable that indicates whether the respondent of the household has indicated any credit turned down, bankruptcy, foreclosure, or late payments during the prior five years. To construct our model, we also create interaction terms to capture the differences among African American households based on respondent’s use of financial planner, gender, and education level. To estimate the impact of a financial planner on an African American (Black) entrepreneur’s credit profile, we test our main logistic regression model in Equation (1).

In Equation (1), Bad_Crediti* is the unobserved latent variable with respect to Bad_Crediti in the setting of logistic regression model, and Bad_Crediti is a dummy variable that equals “1” if respondent i indicates that they have had a credit application turned down, bankruptcy, foreclosure, or late payment in the prior five years, and “0” otherwise. Blacki is a dummy variable that equals “1” if respondent i is self-identified as Black race (African American), and “0” otherwise. Planneri is a dummy variable (not used in regression) that equals “1” if respondent i indicates that they have used financial planners, accountants, or lawyers in making borrowing and investment decisions, and “0” otherwise.8Black_Planneri is an interaction term that equals the multiplication of Blacki and Planneri, and is also by design a dummy variable that equals “1” if respondent i is an African American who has also used a financial planner, and “0” otherwise. The use of the interaction term here can potentially capture the statistical difference of the probability of “bad credit” between African Americans who use financial planners and those who don’t. Likewise, Black_Femalei is an interaction term (also a dummy variable) that equals “1” if respondent i is an African American female, and “0” otherwise. Black_Collegei is an interaction term (also a dummy variable) that equals “1” if respondent i is an African American who attended college, and “0” otherwise. We also include several important control variables in our model as described below. Age_Groupi is a categorical variable that equals “1” if respondent i is less than 35 years old, or “2” if respondent i is in the 35–44 age group, or “3” if respondent i is in the 45–54 age group, or “4” if respondent i is in the 55–64 age group, or “5” if respondent i is in the 65–74 age group, or “6” if respondent i is 75 years or older. Net_Asseti is the net worth of respondent i (in $ millions and 2019 dollar terms); Household_Incomei is the household income of respondent i in the previous year of the survey (in $ millions and 2019 dollar terms); Business_Incomei is the business income (from sole proprietorship, farm, etc.) of respondent i in the previous year of the survey (in $ millions and 2019 dollar terms); Yes_Fin_Riski is a dummy variable that equals “1” if respondent i states that they are willing to take financial risk, and “0” otherwise.

Summary Statistics and Results

Table 1 Panel A shows the summary statistics for all 9,522 self-employed households. On average, 16.5 percent of respondents had some form of bad credit, and 57.7 percent of respondents indicated that they used financial planners for making borrowing and investing decisions. Among all households surveyed, only 3.9 percent respondents are African Americans and 7.4 percent respondents are females. The average age of all respondents is around 54, and the average net asset of all entrepreneurs is $34.63 million (in 2019 dollars). Since the net asset of all survey respondents is highly skewed toward wealthy households, the median net asset of all self-employed households is a much lower $3.50 million (in 2019 dollars). Table 1 Panel C and Panel D present summary statistics by different race for self-employed households. We can see that among all races, African American households have the highest percentage of bad credit (36.3 percent), compared to non-Hispanic White (14.3 percent), Hispanic (35.9 percent), and other races (18.8 percent). Also, African American households have the lowest median net asset ($0.148 million), compared to all other races.

Table 2 presents our logistic regression results and our main findings after controlling for factors including age, gender, education, wealth, income, and individual risk aversion. Marginal probabilities d[P=prob(bad_credit=1)]/dx are also estimated for our main logistic regression Equation (1).9 Equations (2)–(5) are variations of Equation (1) and represent different combinations of control variables, for robustness check purpose. For Equation (1), with the average of predicted probability of bad credit to be 13.1 percent, we estimate that African American entrepreneurs are 10.2 percent more likely to have bad credit compared to this average, which is about 78 percent more likely in relative terms.10 However, African American entrepreneurs who work with financial planners are about 4.4 percent less likely to have bad credit than those who don’t, which implies that African American entrepreneurs who work with financial planners are only 5.8 percent more likely to have bad credit than the average. The results also show that African American women are even more likely to have bad credit compared to Black men (10.6 percent more likely), while there is no significant credit difference between African American entrepreneurs who have attended college and those who haven’t. Results also show that older respondents are about 4.2 percent less likely (per 10-year age gap) to have a bad credit profile than younger respondents, while respondents who are willing to take financial risks are 3.4 percent more likely to have a bad credit profile than those who are not willing, after controlling all other factors. These results discussed above are both economically and statistically significant.

The Role of Financial Planners

Our empirical analysis suggests that AAB owners who engage in the services of financial planners have better credit profiles, which would in turn, potentially lead to better access to capital via bank lending. Also, we show that AAB owners who are female, younger, and/or those who are less risk averse are more likely to have a bad credit profile than other AAB owners. Financial planners can use this awareness to work with AAB owners to improve their credit profiles and access to capital, and to identify certain groups of African American clients with the potential to make a greater impact. The remainder of this section reviews several ways financial advisers can improve their efficacy in assisting AAB owners in improving business outcomes, with an emphasis on utilizing decentralized finance as a means for obtaining capital and mitigating the discrimination risk inherent in obtaining credit from traditional banking institutions.

Capital Acquisition Services

One of the most critical services advisers can provide is to successfully engage AAB owners in comprehensive financial planning services to enhance their chances of obtaining capital for their business. These services could include:

- Debt management

- A significant emergency fund to pay personal expenses during the startup and growing phase

- Cash flow and budgeting

- Having adequate life, health, and property/liability insurance

- A diversified investment portfolio

- Reducing tax liability and ensuring tax reporting is completed and on time

- Adopting a qualified retirement plan

- Ensuring a business succession plan is in place along with the proper estate documents such as wills, durable POAs, living wills, and medical POAs

Advisers can also provide business capital acquisition services in their business model. This could include these aspects:

- Credit score monitoring and improvement, and personal credit attributes as part of the service offering or as a standalone service. A standalone service could also help alleviate the aversion to a fee-based pricing model. Advisers can also help clients work with lenders by providing documentation and reporting to lenders their personal financial situation to enhance loan approval (while maintaining privacy and confidentiality).

- Consider an alternative revenue model that has a “ramp-up” feature that starts with fees that just cover overhead, and over time increase to more economically appropriate levels. Of course, any revenue model must be cleared with compliance departments.

- Identify alternative sources of capital for business owner clients instead of just relying on networks of investors and lenders. These sources may include loans and grants from foundations advocating for minority business ownership, community organizations, and government programs that are offered primarily to minorities and African Americans. For example, Minority Entrepreneur Development Association (MEDA) has offices in over 39 cities and provides business consulting needs for Black and minority entrepreneurs. MEDA also assists owners in working with banks to provide capital. In addition, the Expanding Black Business Credit Initiative (EBBC) is an organization dedicated to assisting African American entrepreneurs in overcoming the credit gap by partnering with community development financial institutions to “expand Black business credit by 250 percent over the next three to five years.” Furthermore, as mentioned previously, many community banks are part of the Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFI) Program, and with the financial and technical assistance CDFIs receive from the federal government, they can greatly support the access of capital in low-income and underserved communities.

- In addition, a rapidly expanding area of lending called decentralized finance can be an alternative source of funding that is worth exploring. Decentralized finance (DeFi) is similar to peer-to-peer lending in that investors can lend directly to business owners. The DeFi system relies on cryptocurrency and blockchain technology and utilizes a public ledger to record transactions. Investors make investing offers with “smart contracts” that outline the lending terms. Individuals then accept the contracts, or alternatively, the contracts are automatically accepted based on pre-determined criteria. Stephen Ritter (2021) writing in Forbes reported that the DeFi system is completely anonymous, which eliminates any potential for bias or discrimination.

Build Confidence Through Financial Education and Counseling

To address the lack of education and experience, advisers should promote financial education. Financial literacy through financial education has been successful in leading to better decision-making (Yakoboski, Lusardi, and Hasler 2020). Many financial education initiatives are delivered through schools, workplaces, and community and neighborhood centers. In addition, financial counseling is a therapeutic approach that focuses on reducing financial stress and improving financial well-being by working with individuals on establishing (or re-establishing) behavioral changes to alleviate stress and anxiety and to improve financial wellness. This service could be particularly helpful to boost confidence when applying for capital. Collins and O’Rourke (2010) found that financial counseling leads to more successful outcomes for those that need these types of services. Counseling is an effective approach when the focus is on debt management or improving credit scores, and can help improve confidence when applying for loans, which can help overcome the fear of applying.

Conclusion and Future Research

In this paper, we address the issue of closing the “wealth gap” among African American business (AAB) owners by examining the association between AAB owners’ use of financial planners and their credit profile, and we found a positive relationship between the use of financial planners and better credit profile among AAB owners. We also discuss the roles financial planners can play in improving successful borrowing outcomes for AAB owners.

Future research in this area could go broader and deeper into the examination of lack of access to capital by AAB owners. Broadly speaking, examining alternative sources of capital could be an interesting and perhaps fruitful area to pursue. This paper examines undercapitalization of AAB owners in terms of lack of access to capital and the positive role that personal financial planning could play in terms of capital via bank borrowing. As stated previously, there are several potential sources of capital accessible to AAB owners and entrepreneurs in general. Each could be unique and interesting future research opportunities.

Citation

Chen, Leon, Sophia Duffy, and Daniel Hiebert. 2022. “The Role of Financial Planners on African American Business Owners’ Personal Credit and Access to Capital.” Journal of Financial Planning 35 (11): 66–79.

Endnotes

- “Bad credit” is a dummy variable that indicates whether the respondent of the household has indicated any credit turned down, bankruptcy, foreclosure, or late payments during the past five years. The details of the variables are explained in the Empirical Analysis section.

- See www.cdfifund.gov/programs-training/programs/cdfi-program. We thank an anonymous reviewer for bringing this information to our attention.

- Some of these findings contrast with previous positive usage findings by other researchers (Grable and Joo 2001).

- Grable and Joo (2001) find that those with higher risk tolerance tended to use financial planners.

- See www.federalreserve.gov/econres/aboutscf.htm.

- Data from survey years earlier than 1998 do not have information related to the use of financial planners, and thus are not used.

- See Q9 and A9 of FAQs: www.federalreserve.gov/econres/scf_faqs.htm.

- We consider a slightly broader definition of “financial planner,” which also includes accountants and lawyers if they contribute to advising clients on borrowing and investment decisions. Also, we consider the use of financial planner as an exogenous variable in our model, and we additionally tested that the use of financial planners is not statistically associated with the fear of credit denial among all entrepreneur households.

- Marginal probability measures the change of probability of bad credit when there is one unit change of each independent variable in Equation (1), in the setting of the logistic regression. This statistic is useful because the coefficients obtained from the logistic regression model do not represent marginal probabilities, since the dependent variable is a latent variable that does not represent true probability.

- All probability comparisons in this section are in absolute terms, unless specified otherwise.

References

Becker, Gary S. 1962. “Investment in Human Capital: A Theoretical Analysis.” Journal of Political Economy 70 (5): 9–49.

Breen, John, Cheryl Calvert, and Judy Oliver. 1995. “Female Entrepreneurs in Australia: An Investigation of Financial and Family Issues.” Journal of Enterprising Culture 3 (4): 445–461.

Cavalluzo, Ken S., Linda C. Cavalluzo, and John D. Wolken. 2002. “Competition, Small Business Financing, and Discrimination: Evidence from a New Survey.” The Journal of Business 75 (4): 641–679.

CFP Board. 2015. Financial Planning Competency Handbook. John Wiley & Sons.

Chrisman, James J., Jess H. Chua, Pramodita Sharma, and Timothy R. Yoder. 2009. “Guiding Family Businesses Through the Succession Process.” The CPA Journal 79 (6): 48–51.

Collins, Michael, and Collin O’Rourke. 2010. “Financial Education and Counseling—Still Holding Promise.” Journal of Consumer Affairs 44 (3): 483–498.

Ergungor, Ozgur E. 2010. “Bank Branch Presence and Access to Credit in Low- to Moderate-Income Neighborhoods.” Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 42 (7): 1321–1349.

Fairlie, Robert W. 1999. “The Absence of the African American Owned Business: An Analysis of the Dynamics of Self-Employment.” Journal of Labor Economics 17 (1): 80–108.

Fairlie, Robert W. 2010. “Disparities in Capital Access between Minority and Non-Minority-Owned Businesses: The Troubling Reality of Capital Limitations Faced by MBEs.” Minority Business Development Agency, U.S. Department of Commerce. www.mbda.gov/sites/default/files/migrated/files-attachments/DisparitiesinCapitalAccessReport.pdf.

Fairlie, Robert W., and Alicia M. Robb. 2007. “Why Are Black-Owned Businesses Less Successful than White Owned Businesses? The Role of Families, Inheritances, and Business Human Capital.” Journal of Labor Economics 25 (2): 289–323.

Fan, Wei, and Michelle J. White. 2003. “Personal Bankruptcy and the Level of Entrepreneurial Activity.” The Journal of Law and Economics 46 (2): 543–567.

Grable, John, and So-Hyun Joo. 1999. “Financial Help-Seeking Behavior: Theory and Implications.” Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning 10 (1): 14–25.

Grable, John, and So-Hyun Joo. 2001. “Factors Associated with Seeking and Using Professional Retirement-Planning Help.” Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal 30 (1): 37–63.

Howell, Sabrina T., Theresa Kuchler, David Snitkof, Johannes Stroebel, and Jun Wong. 2022. “Automation and Racial Disparities in Small Business Lending: Evidence from the Paycheck Protection Program.” NBER Working Paper No. 29364. www.nber.org/papers/w29364.

Jurinski, James J., Jon Down, and Madhuparna Kolay. 2016. “Helping Older, Encore Entrepreneurs Anticipate Financial Risks.” Journal of Financial Service Professionals 70 (1): 81–90.

Kennickell, Arthur B. 1998. “Multiple Imputation in the Survey of Consumer Finances.” Working paper. www.federalreserve.gov/pubs/oss/oss2/papers/impute98.pdf.

Mittra, Sid, Anandi Sahu, and Harry Starn. 2012. Practicing Financial Planning for Professionals. 11th Edition. American Academic Publishing.

Mitchell, Bruce, and Juan Franco. 2018. “HOLC ‘Redlining’ Maps: The Persistent Structure of Segregation and Economic Inequality.” National Community Reinvestment Organization. https://ncrc.org/holc/.

Ritter, Stephen. 2021. “Three Big Myths about Decentralized Finance.” Forbes. www.forbes.com/sites/forbestechcouncil/2021/11/17/three-big-myths-about-decentralized-finance/?sh=157d1ed97c54.

White, Kenneth J., and Stuart J. Heckman. 2016. “Financial Planner Use Among Black and Hispanic Households.” Journal of Financial Planning 29 (9): 40–49.

Winchester, Danielle, and Sandra Huston. 2013. “Keeping Your Financial Planner to Yourself: Racial and Cultural Differences in Financial Planner Referrals.” The Review of Black Political Economy 40: 165–184.

Yakoboski, Paul, Annamaria Lusardi, and Andrea Hasler. 2020. “Financial Literacy, Wellness, and Resilience Among African Americans.” Teachers Insurance and Annuity Association of America (TIAA). www.tiaainstitute.org/about/news/financial-literacy-wellness-and-resilience-among-african-americans.