Journal of Financial Planning: September 2025

NOTE: Please be aware that the audio version, created with Amazon Polly, may contain mispronunciations.

Executive Summary

- Financial planners are well-trained in technical skills, but desire additional training in addressing client pain points (e.g., cognitive, emotional, or relational issues associated with the “psychology of financial planning” domain) and crisis-related events. This study surveyed 172 financial planners to identify the most common pain points and crises they encounter.

- Practitioners’ most considerable pain points included managing financial abuse, family conflicts, and financial transparency between couples, highlighting the need for training in family systems theory and conflict resolution.

- Planners see gaps in the current learning objectives, particularly in facilitating behavior change, managing grief, and handling complex family dynamics such as divorce and dependent adult children.

- There is a need for training to address financial abuse, make mental health referrals, and mediate family conflicts, indicating the need for better preparation in dealing with sensitive, emotionally charged situations.

- The most frequent client crises involve loss (death of a loved one) and divorce, emphasizing the need for expanded training in grief and crisis management within the financial planning process.

- Planners should clearly articulate to clients the boundaries of their professional competence. Additional training may help advisers better support their clients on a human-to-human level.

Megan McCoy, Ph.D., LMFT, AFC, CFT, is an associate professor in the personal financial planning department at Kansas State University. She is the co-associate editor of Financial Planning Review.

Billy Spencer, CFP®, TPCP, FBS, CFT, is a wealth manager and director at Crestwood Advisors in Boston, MA. He is also a graduate of Kansas State University’s master’s in personal financial planning program.

Blake Gray, Ph.D., CFP®, is an assistant professor in the personal financial planning department at Kansas State University. He is also the faculty consultant for Powercat Financial at Kansas State.

Shane Heddy, FBS, is a Ph.D. student in the personal financial planning program at Kansas State University. He is also the director of planning at Legacy Financial Group in Grand Blanc, MI.

Donovan Sanchez, CFP®, is a financial planning instructor at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, a Ph.D. student in the personal financial planning program at Kansas State University, and a senior financial planner with Model Wealth, Inc.

NOTE: Click on the images below for PDF versions.

JOIN THE DISCUSSION: Discuss this article with fellow FPA Members through FPA's Knowledge Circles.

FEEDBACK: If you have any questions or comments on this article, please contact the editor HERE.

A core mission of the Certified Financial Planner Board of Standards, Inc. (CFP Board) is to ensure the relevance of examination and educational content for CFP® practitioners. This is achieved by conducting a Practice Analysis Study every five years. The 2020 Practice Analysis Study significantly revised the learning domains in the financial planning program curriculum and the certifying exam. One notable change was the introduction of a new domain, the “psychology of financial planning,” which encompasses behavioral finance, sources of money conflict, counseling principles, effective communication, and severe crisis events. This domain and its topics were first incorporated into the March 2022 exam, prompting curriculum updates by educators in 2021 (Salinger 2021). CFP Board-registered programs are now required to include this domain in their curricula, either by adding a dedicated course or by incorporating the content into existing classes. Financial planners who graduated before the curriculum was implemented have had to seek out their own training opportunities in these areas through webinars, workshops, and conference presentations.

Since the initial rollout of the “psychology of financial planning” domain, no research has been conducted to assess the adequacy of the domain or the effectiveness of the associated training. This paper seeks to fill that gap by examining trends in client-presented issues and identifying the competencies and skills practitioners feel they lack in addressing these challenges. Specifically, we explore practitioner pain points related to client psychology needs based on CFP Board’s “psychology of financial planning” learning objectives. To investigate this, we developed the following research questions:

RQ1: What are the most considerable pain points financial planners are facing related to the psychology of financial planning in their practices?

RQ2: Are the current “psychology of financial planning” knowledge topics comprehensive, or do more need to be added to address what planners are seeing in the field with clients?

RQ3: What “psychology of financial planning” training do planners need?

Additionally, particular attention was given to the “crisis events with severe consequences” learning objective within the “psychology of financial planning” domain, which addresses the most common crisis events encountered by financial planners. This part of the paper is modeled after Dubofsky and Sussman (2009), who found that planners often deal with not only financial crises, but also emotional and relational crises stemming from “human drama and frailties: religion and spirituality, death, family dysfunction, illness, divorce, and depression” (Dubofsky and Sussman 2009, 48). Consequently, the final research question in this study became:

RQ4: What crises do planners observe their clients facing in their practice?

Literature Review

Financial planning is a relatively young field, with the first class of CERTIFIED FINANCIAL PLANNER® (CFP®) professionals graduating in 1973 (Lawson and Klontz 2017; Yeske 2016). Early practitioners primarily focused on product sales—pitching insurance and investment vehicles—before transitioning into deeper technical competencies involving portfolio design, tax minimization, and retirement strategies (Lurtz 2024). In more recent years, financial planners have faced ongoing disruption from automated advisory platforms, intensifying the need to go beyond numeric calculations and differentiate through “human” skill sets (Fortin et al. 2020).

Financial planners who utilize strong communication skills gain a deeper understanding of clients’ values around money and create successful planning outcomes and stronger client retention (Anderson and Sharpe 2008). What is fascinating is that in this initial study, clients reported that planners were effective at communication skills, while planners were rather critical of themselves. However, in a more recent study replication, the results were reversed, with planners self-reporting higher communication skills than their clients, suggesting a disconnect between the perceptions of clients and planners (McCoy et al. 2022). Modern clients had higher expectations for planners to deliver on their interpersonal communication, and planners were overconfident in their own abilities. This suggests the need for further development of education and training in communication around the psychology of financial planning.

This project is not the first to suggest that the role of financial planners is evolving from financial analytics to coaching and life planning. Dubofsky and Sussman (2009) suggested a significant shift in the responsibilities and focus of financial planners as evidenced by the fact that approximately a quarter of respondents’ interactions with clients were devoted to non-financial issues, and 74 percent of planners estimate that the time they spend on these issues has increased over the past five years. Their study further highlights that financial planners are dealing with a range of non-financial issues, such as conflict, grief, and mental illness. Subsequent studies confirm that clients increasingly seek empathetic advisers who can guide them through major life transitions such as marriage, divorce, grief, and retirement—all of which involve both financial and emotional stakes (Britt 2016; Green 2010; Lurtz et al. 2020).

Given this broader context, the CFP Board updated its curriculum to include a new “psychology of financial planning” domain, reflecting a heightened emphasis on “soft skills” and psychosocial competencies—such as interpersonal communication, counselor-like listening, and conflict mediation—alongside technical expertise (Salinger 2021). However, we still don’t know if these competencies cover all the skills planners actually need or if more should be added. We also lack evidence that they capture the real, day-to-day challenges planners face with clients. Without such research, we risk leaving planners unprepared for the psychological and relational issues that can arise in practice.

A particularly urgent area in which emotional competence is paramount involves crisis events. Clients routinely seek professional guidance while facing crises such as job losses, severe medical diagnoses, or the death of loved ones (Dubofsky and Sussman 2009; Chatterjee and Fan 2021). These high-stress periods often trigger heightened emotions—ranging from anxiety to profound grief—that inevitably filter into financial decision-making. For instance, a grieving client might struggle to tackle estate paperwork, or someone in the throes of divorce could be immobilized by conflict with a former partner (Biever et al. 2021; Kleingeld 2023). Even when planners excel at technical solutions—like reconfiguring budgets or recalibrating retirement plans—their actual challenge may lie in keeping the client emotionally engaged and capable of following through.

Despite the clear prevalence of such issues, many financial advisers feel ill-equipped to fully address them, often citing insufficient training on grief support, crisis management, or mental health interventions (Byram et al. 2024). This gap has led some scholars to advocate for a deeper integration of theories like the transtheoretical model of behavior change (Prochaska and DiClemente 1983), motivational interviewing (Miller and Rollnick 2012), and practical guidelines for making mental health referrals (Horwitz and Klontz 2013). In parallel, organizations such as the Financial Therapy Association offer webinars that further prepare advisers to address the real-life “psychology of money” in a professional yet empathetic manner (Financial Therapy Association n.d.).

Ultimately, the CFP Board’s new “psychology of financial planning” domain signals that crises, behavioral biases, and interpersonal conflicts are not fringe topics but core aspects of modern advising (Salinger 2021). As more clients seek holistic, life-centered guidance, the profession will likely continue evolving toward a balanced blend of technical acumen and empathetic, psychologically informed practice. Yet, translating these curriculum updates into daily professional competency remains an ongoing challenge. This study can help determine best practices for equipping planners with the tools—and professional boundaries—to guide clients through the some of the most emotionally charged financial crossroads of their lives.

Methods

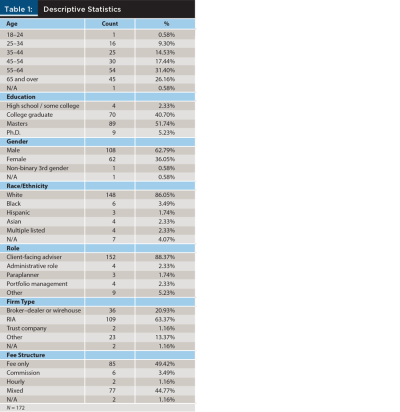

The study was conducted in collaboration with the Financial Planning Association® (FPA®); an IRB-approved electronic survey was distributed to its members and shared on social media alongside the research team. The survey received 184 responses. Twelve of those respondents did not answer the crisis nor demographics questions. They were removed from the analysis resulting in a final sample of N = 172. A few of the remaining respondents objected to providing age, gender, and/or race/ethnicity responses resulting in several responses being listed as N/A. The characteristics of the sample are detailed in Table 1.

The survey was built with two source materials in mind: (1) CFP Board’s “psychology of financial planning” learning objectives and (2) the financial planning crises listed in Dubofsky and Sussman (2009). However, there were some changes made to how source materials items were presented in the survey. For example, the CFP Board learning objectives are not intended to be used as survey questions. As such, some edits were made to these to clarify language, reduce questions that may ask multiple questions but allow for one answer (e.g., double-barreled), and avoid confusion for participants. Each of the survey questions were measured on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from easy to difficult. Table 2 provides an overview of those changes.

These questions based on the learning objectives were then followed by an open-ended question asking planners to identify which of the pain points were missing from the list.

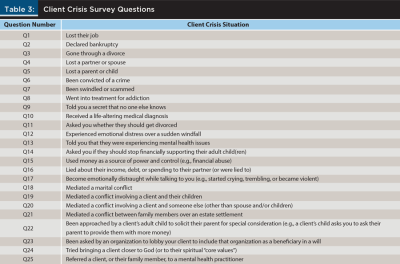

The second source material came from the list of crises included in a prior study. This prior study by Dubofsky and Sussman (2009) included two different lists of questions regarding the crises experienced by planners. The length of our survey prohibited the use of both of their lists of crises, so their two lists were reduced based on which ones were most applicable to planners in 2009. For instance, their list of crises included asking planners whether they had assisted clients in obtaining drug treatment. However, because only 3.1 percent of respondents reported experiencing this, it was ultimately removed. The list of crisis events that were asked can be found in Table 3.

Results and Discussion

The following section presents the descriptive results of the study, emphasizing the broader implications for the financial planning profession and future research. The findings shed light on challenges that financial planners and their clients face and provide insight into the real-world application of CFP Board learning objectives. These results highlight key areas where additional knowledge or training may be needed. This section also outlines the types of crises commonly encountered by clients in the practices of financial planners. This discussion can help shape future educational content, inform professional development, and guide planners in addressing their clients’ evolving client psychology needs.

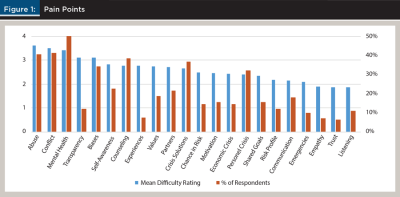

RQ1: What are the most considerable pain points financial planners are facing related to the psychology of financial planning in their practices? Pain points refer to specific challenges identified during client interactions. These 22 challenges were derived from CFP Board’s “psychology of financial planning” learning objectives. As noted in Figure 1, the pain points ranked as most difficult include (1) addressing financial abuse, control, and power in client relationships (ABUSE), (2) mediating financial conflicts within client families (CONFLICT), (3) knowing how or to whom to make a referral to a mental health practitioner (MENTAL HEALTH), (4) ensuring that couples are being honest about their finances with each other (TRANSPARENCY), and (5) identifying how cognitive biases and heuristics impact a client’s decision-making (BIASES). The question is measured on a 5-point Likert scale, from easy (1) to difficult (5).

Three of the top five points (ABUSE, CONFLICT, and TRANSPARENCY) relate to managing interpersonal relationships inside financial planning offices and makes a case for introducing family systems theory (Bertalanffy 1968) into financial planning. Family systems theory views the family as an interconnected and interdependent system where each member’s behavior affects and is affected by the other members. This emphasizes the importance of understanding family dynamics and interactions to address individual and relational issues. Training in family systems theory could enable practitioners to address issues of financial abuse, conflict, and transparency from a lens of examining patterns of behaviors between individuals rather than being housed within one person (Britt 2016).

Additionally, two pain points (CONFLICT and TRANSPARENCY) relate to couples communicating about money in healthier ways. Financial planners may benefit from training to help mediate conflict resolution and help clients to be more assertive so couples can speak openly and with empathy to one another. Finally, practitioners identified ABUSE as the most difficult skill to manage. Financial abuse is a broad term that describes how money can be used as a source of power to control another person (Byram et al. 2024). There are multiple types of financial abuse and control issues, although two are the most prevalent: intimate partner financial abuse (Postmus et al. 2020) and elder financial abuse (Acierno et al. 2020). Training financial planners to recognize and act on abuse signs could potentially prevent abuse from escalating.

The pain points that were selected least often were: (1) apply active listening when working with your clients (LISTENING), (2) establish trust in client relationships (TRUST), (3) demonstrate empathy while navigating a client crisis (EMPATHY), (4) assist clients in preparing for potential future financial emergencies (EMERGENCIES), and (5) use communication techniques for more effective client communication (COMMUNICATION). Surprisingly, the aspects selected as least difficult are actually the most common solutions to the core challenges financial planners identified as most critical pain points. Furthermore, prior research has shown that these factors are highly correlated, with listening and communication skills being one of the largest contributing factors to building trust with clients (McCoy et al. 2022). McCoy et al. (2022) replicated the study completed by Anderson and Sharpe (2008), revealing a significant decline in clients’ perceptions of planners’ communication skills compared to the original research, where planners underestimated their abilities. This shift suggests that planners should avoid overestimating their skills and acknowledge the importance of effective communication and listening in building client trust.

Empathy was also rated as relatively easy. Empathy is an art that has gained notoriety through the work of Brené Brown (2021). She explains that we often mistake empathy for sympathy. While sympathy is the process of feeling bad for someone when something bad happens to them, empathy is much more difficult. It is the process of putting oneself in another’s shoes and reflecting on what they may be feeling. Often, practitioners will not have gone through the same experiences as their clients, but they can build skills to empathize with the underlying feelings clients are experiencing and try to find ways to demonstrate their understanding without projecting their own experiences on them (Smodic et al. 2019). This is not an easy process and should be taken seriously.

The final pain point rated as relatively easy for planners is assisting clients in preparing for potential future financial emergencies (EMERGENCIES). Planning for emergencies is the essence of financial planning. CFP Board’s knowledge topics outside of the “psychology of financial planning” are heavily quantitative and include professional conduct and regulation, general principles of financial planning, risk management and insurance planning, investment planning, tax planning, retirement savings and income planning, and estate planning. It is not surprising that those who work as financial planners would find themselves well prepared for this challenge.

The primary objective of this research question was to identify the most challenging aspects of client interactions and dynamics in their financial planning practice. This also provided the opportunity to explore the practical applicability of CFP Board’s “psychology of financial planning” learning competencies. This process assessed whether these competencies are theoretically sound, and whether they are pertinent and applicable to the day-to-day experiences and challenges faced by financial planners.

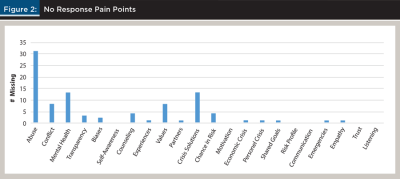

In rating these pain points, respondents were told to answer N/A if the question was not applicable to their work with clients. Figure 2 displays the number of respondents who gave no response to the difficulty rating. The three pain points that were skipped or answered N/A most often were: (1) How difficult is it to address financial abuse, control, and power in client relationships? (ABUSE); (2) How difficult is it to know how or to whom to make a referral to a mental health practitioner? (MENTAL HEALTH); and (3) How difficult is it to communicate potential solutions, including government-offered solutions, during crises? (CRISIS SOLUTIONS).

Note that ABUSE was rated one of the most difficult competency areas, as well as one of the most not applicable to financial planners, highlighting the confusion in the role of the planner on if, when, and who to make mental health referrals. Financial advisers appear well trained and feel responsible for core financial planning tasks like dealing with risk profiles, building shared goals, and other core tasks. However, the most difficult topics are also the topics planners feel are outside of their purview. This may result in undertraining and lack of preparation making these difficult situations more difficult than if they had received adequate training.

RQ2: Are the current “psychology of financial planning” knowledge topics comprehensive, or do more need to be added to address what planners are seeing in the field with clients? This study’s second question explored whether planners identified additional pain points that are not currently included in CFP Board’s learning objectives. Should the CFP Board consider broadening these learning objectives, the responses could potentially be used as a starting point for expansion. Responses were categorized into the current knowledge topics. The key areas that planners need more support in working with clients are: (1) facilitating behavior change by identifying motivation and getting follow-through from clients, (2) family conflict including parenting, divorce, using money for control, and financial boundaries with adult children, and (3) crisis events with severe consequences, primarily the death or decline of a spouse.

First, the primary frustration of respondents was that clients did not follow through or implement recommendations. In some cases, advisers report that clients ignoring advice or directly contradicting recommendations were especially painful. A significant number of respondents also reported difficulties in facilitating behavioral change in clients. CFP Board’s learning objectives currently include only one pertaining to motivation within the learning objective “sources of money conflict.” This objective, identifying a client’s motivation for achieving their goals, is somewhat vague and wide-ranging. Motivation identification is only one facet of aiding clients in behavioral change. Practitioners also need skills in handling client ambivalence or resistance to change (Horwitz and Klontz 2013). This could be enabled through training that provides an understanding of the various types of behavioral change theories (e.g., transtheoretical change model; Prochaska and DiClemente 1983) or through interventions that can aid in behavioral change (e.g., motivational interviewing; Miller and Rollnick 2012).

Planners also discussed difficulties navigating the emotional and psychological aspects of divorce. Although there are CFP Board learning objectives that cover the financial implications of divorce, such as its effects on taxes and estate planning, there are no “psychology of financial planning” objectives related to addressing client needs that are going through divorce. Financial planners should be proficient in analyzing the financial implications of divorce, including asset division, alimony, child support, and tax status changes. But perhaps a value add to many financial planners’ practice could be also providing support and resources that enable clients to navigate their emotional distress and make informed decisions. Furthermore, divorce necessitates a need to coordinate with other professionals (such as attorneys) to provide integrated financial and legal advice. Due to how often divorce came up for our sample of practitioners, it may suggest a need for more learning competencies in this area. Practitioners need to recognize that the divorce usually occurs after an extended period of relational and emotional distress (Kleingeld 2023). It should be seen as a period of grief for the client who is losing both the partner they had once loved, as well as grieving the loss of the life they once anticipated having with their partner.

Another difficulty highlighted by planners was working with grieving clients. Although the CFP Board’s learning objectives mention adverse health events, they do not specifically address death, dementia, and grief (including anticipatory grief)—issues that have become increasingly common with the realities of an aging population (Chatterjee and Fan 2021). As individuals live longer, financial planners are more likely to encounter health-related and end-of-life concerns among older clients, requiring them to navigate not only complex financial matters but also the emotional and relational challenges that accompany bereavement (Smodic et al. 2019). Providing effective support for grieving clients can often involve empathetic communication, the coordination of professional referrals (e.g., mental health counselors, hospice or palliative care experts, attorneys), and guidance through legal and estate planning processes. While these needs could be incorporated under existing learning objectives related to crisis events, the high frequency of such cases underscores a potential gap in current curricula, suggesting that more specific learning competencies are necessary to help planners address death, dementia, and various forms of grief (Smodic et al. 2019).

The handling of sudden money or a windfall was also identified as a challenge in the open-ended responses. This suggests the need for a knowledge topic focused on client socioeconomic transitions, addressing the emotional aspects of changes involving a client’s economic situation. These transitions can significantly alter a client’s lifestyle (Anthes and Lee 2002). Thus, understanding how to navigate these situations, or knowing who to refer a client to for additional help, could greatly benefit clients and foster stronger relationships. One example of a resource is The Sudden Money Institute (www.suddenmoney.com/), which was developed as a resource center for financial planners to understand financial transitions.

A few planners also expressed a need to assist clients who have adult children still dependent on financial support. This situation presents challenges for planners on both sides of the equation. Clients often feel emotional and frustrated, torn between their desire to support their children and the urge to reduce or eliminate that support, leaving them uncertain about how to navigate these complex feelings. Simultaneously, providing financial assistance can significantly hinder the client’s overall financial plan as well as delay financial independence and the development of financial self-efficacy (Lee and Mortimer 2009). While planners should be careful to understand a client’s values and reasons why they continue supporting their children, this can be a sticky issue. Tennerelli et al. (2019) provides insight into when the financial support of adult children can be a supportive practice of scaffolding their financial future (e.g., supporting their education, providing a safety net during a short-term financial crisis) or when it is an example of enabling the ineffective financial practices that hold them back from independence. Although both are helpful articles, they are not based on empirical research, which is needed to understand evidence-based best practices for planners.

Some existing learning objectives could benefit from further development. For instance, the “sources of money conflict” learning objective identifies potential conflict areas but lacks guidance on resolving disputes between spouses and family members. The objective addressing “client and planner attitudes, values, and biases” overlooks the planner’s own biases and attitudes. Similarly, while the “principles of counseling” objective covers trust-building, it doesn’t provide strategies for repairing broken trust. Additionally, planners expressed a need for more training on the “psychology of financial planning” and its practical integration into their businesses. This suggests that the current knowledge topics may be too broad, and that additional training is needed on how to implement these topics within financial planning firms.

RQ3: What “psychology of financial planning” training do planners need more of? As a follow-up to the pain points found most challenging with their clients, planners were asked which training areas they felt they needed the most. The areas identified for additional training included (1) addressing financial abuse, control, and power dynamics in client relationships (ABUSE); (2) understanding how to identify appropriate mental health referrals (MENTAL HEALTH); and (3) mediating financial conflicts within client families (CONFLICT). Please see Figure 1 for a full list of pain points and which areas they found most difficult.

Notably, ABUSE and MENTAL HEALTH were among the pain points that planners frequently skipped, suggesting that while these issues may not be encountered regularly, planners recognize their potential significance. This desire for preparedness indicates a gap in current training, as many planners feel ill-equipped to handle such sensitive matters. Planners may also view these as outside their scope and responsibility, so an answer of N/A could mean, “We see these but don’t deal with them because it is not our role.” It also could be that these topics hover on the edge of the scope of competence issues for planners, particularly regarding the ethical implications of acting as unlicensed mental health professionals. However, it is important to emphasize that the most requested training was on MENTAL HEALTH, indicating that CFP Board should consider including this competency in its learning objectives and that planners should consider gaining additional skills in this area.

The desire for training on CONFLICT aligns with existing research indicating that financial disputes are qualitatively different from other types of conflicts. For example, they tend to last longer, are less likely to be resolved, and often spill over into other areas of clients’ lives (Dew and Stewart 2012). To address these training needs, financial planners could benefit from targeted workshops or courses that focus on mediating financial conflicts within client families. Collaborations with mental health professionals and accredited institutions may provide planners with essential skills and knowledge. Additionally, the Financial Therapy Association (n.d.) provides monthly webinars that occasionally cover topics relevant to these needs, offering planners further opportunities for professional development.

Some notable findings deserve attention. Occasionally, planners identified challenges in certain areas but did not request training. Two significant examples include the impact of a lack of financial transparency on clients and their loved ones (TRANSPARENCY) and the importance of avoiding personal biases in planning recommendations (SELF-AWARENESS). Conversely, some respondents rated a pain point as relatively easy yet still sought training. Good examples of this include assessing the impact of personal crises (e.g., job loss, health issues) on client plans (PERSONAL CRISES) and employing communication techniques for more effective client interactions (COMMUNICATION). These observations suggest a research opportunity to further explore the disconnect between the perceived difficulty of a skill and the desire for training in that area, indicating the need for a qualitative approach.

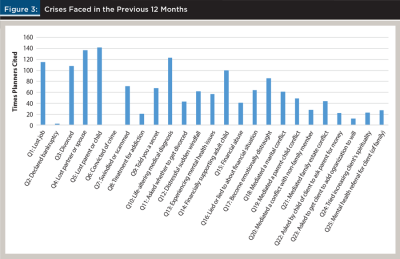

RQ4: What financial crises do planners observe their clients facing in their practice? As can be seen in Figure 3, the most often cited crises were (1) losing a parent or child (79.78 percent); (2) losing a partner/spouse (76.97 percent); (3) receiving a life-altering medical diagnosis (69.49 percent); (4) losing their job (64.61 percent); and (5) going through a divorce (60.67 percent). These findings underscore the significant emotional and psychological challenges that clients bring into the financial planning process. The results support our earlier recommendation for a learning objective on loss and grief, given the frequency with which planners encounter clients grappling with bereavement. Furthermore, the high incidence of divorce as a critical issue reinforces the need for financial planners to develop competencies in managing the financial and emotional complexities associated with divorce.

A comparison with the earlier study by Dubofsky and Sussman (2009), which inspired our current research, reveals notable differences in the emotional responses reported by planners. In their study, approximately 75 percent of planners indicated that clients became emotionally distraught during sessions. In contrast, the present survey indicated a lower figure of around 49 percent. Differing external contexts may explain this discrepancy. The timing of the studies could be a cause of the differences. Dubofsky and Sussman (2009) conducted their study during the Great Recession, a period marked by widespread financial distress, including job losses, home foreclosures, and diminished savings. Such acute financial pressures likely heightened emotional responses during financial planning sessions. The present study, conducted post-COVID-19, may reflect a period of relative emotional recovery, potentially explaining the lower rate of emotional distress observed in the findings. However, had the present study been conducted closer to the peak of the pandemic and the subsequent market downturn, higher levels of emotional distress may have been observed.

One particularly striking finding in this study is the prevalence of death as a significant issue. In the survey, 77 percent to 79 percent of respondents reported the death of a loved one as a common crisis faced by their clients, a figure substantially higher than the 19 percent reported in Dubofsky and Sussman’s (2009) study, where all deaths were grouped together. This disparity may reflect the profound emotional and financial impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, which brought issues of mortality and loss to the forefront for many families.

These results strongly indicate a need for enhanced training in grief, loss, and divorce management for financial planners. These crises are not only frequent but also deeply destabilizing for both clients and planners. As the role of the financial planner continues to evolve beyond traditional financial advice, it is imperative that practitioners develop a deeper understanding of the psychological dimensions of financial planning. By equipping planners with the skills to address both the financial and emotional aspects of these crises, the profession can ensure more comprehensive and empathetic client support.

Limitations

This research has several limitations. CFP Board’s “psychology of financial planning” learning objectives were revised to align with best practices in survey design, which may limit our ability to fully assess them. The survey was primarily promoted through Financial Planning Association (FPA) email campaigns, with additional outreach via social media (e.g., LinkedIn) and direct emails to contacts, which may have brought in respondents from outside of the FPA, but participants were likely skewed toward FPA members and not representative of the full spectrum of financial planners. The sample size is another limitation, and many left the open-ended question blank. This limited participation constrains the research team’s ability to comprehensively view the sample. Future research should seek a more diverse range of financial planners by using additional channels to reach a broader spectrum of the profession.

Implications and Conclusion

Financial planning training has primarily focused on the core technical knowledge and competencies essential to serving clients effectively. However, as Dubofsky and Sussman (2009) note, financial planners regularly engage clients on issues related to cognitive, emotional, and relational issues highlighted within the “psychology of financial planning” domain, and many do not have the training to do so confidently. This paper supports these findings and suggests that planners may benefit from focused training on navigating pain points within CFP Board’s “psychology of financial planning.”

Financial planners in this study expressed a desire for more training related to understanding how to mediate financial conflicts within client families and deal with financial abuse. In their own way, each of these areas carries a gravity that can be intimidating to many planners, and targeted training on identifying and addressing issues related to these topics may be beneficial. This paper suggests that research on how planners can better support clients through grief, divorce, job loss, family conflict, and financial transparency is also warranted. Results from additional research on these topics can inform CFP Board registered training programs on how to help planners support clients who are experiencing these, and other, pain points in their practices.

The pain points that planners see in their practice can be highly sensitive and emotionally charged. Training to help planners become more comfortable navigating conversations toward helping clients seek out mental, or other health, professionals may also be useful. General education to help planners understand how, where, and when it might be appropriate to make a referral to a healthcare professional could also be beneficial. Financial planners may not feel comfortable making recommendations, so training on how to make a referral, what services are offered by different mental health professionals, and how to make referrals to the right professionals may also be beneficial.

A stronger understanding of theoretical frameworks can help practitioners navigate complex human situations. For example, family systems theory (Bertalanffy 1968) may help planners understand how family dynamics influence financial decisions and conflicts. Likewise, behavior change theories (e.g., transtheoretical change model; Prochaska and DiClemente 1983) may help practitioners improve their clients’ financial behaviors. Of course, planners need not be experts in all things, but more familiarization with some theoretical frameworks can serve as additional tools in their toolkit (beyond the traditional financial planning tools) for serving clients.

Being able to recognize areas of concern (e.g., conflict, abuse) is a good first step; however, this project suggests that training in how to discuss, mediate, and resolve conflict could prove helpful. In situations where a client is enabling a capable adult dependent, planners may wonder how to address this issue best—particularly when such financial enabling materially impacts a financial plan. Methods for planners to strategize balancing financial support versus enabling clients’ dependent adult children should be explored. Lastly, many planners are familiar with biases identified by behavioral economics, but do they possess the skills and training necessary for adapting planning recommendations around them?

Once planners have recognized areas of concern, they should consult research with clear application for challenges they face. For example, Asebedo and Purdon (2018) provide a framework for understanding conflict styles and provide specific techniques and framework to help planners mediate conflict within client relationships. Additional research provides information on money conflict and specific guidelines for mediators to use (Benjamin and Irving 2001), how to mediate property distribution disputes during the estate process (Folberg 2009), and how to help widows dealing with grief during the financial planning process (Biever et al. 2021). Challenges exist with the research literature as it is not always specific to financial planning, may not have clear application, may be hard to find and sometimes not even accessible, and may be delivered in styles and formats foreign to financial planners (Naveed et al. 2025).

One question that naturally arises relates to practice boundaries and services being offered. While many planners are interested in how they can better help clients navigate crisis events (say, for example, helping a client who is experiencing mental distress get professional help), financial planners may be less interested in incorporating the therapy or psychology topics into their practice. And this is for good reasons, as most financial planners are not trained or licensed therapists. But at what point does a planner (intentionally or unintentionally) go from acting simply as another caring human for a person in crisis to giving professional advice without the license and training to do so? Financial planners can benefit from targeted training, but they should be careful to clarify where their professional competencies end. While financial planners should always be careful to clearly articulate these boundaries, developing an improved ability for helping clients navigate the inevitable crisis events that they may face can help them be better prepared to support their clients on a human-to-human level instead of a professional-to-client level.

Citation

McCoy, Megan, Billy Spencer, Blake Gray, Shane Heddy, and Donovan Sanchez. 2025. “Exploring Planner Pain Points and Client Crises in the ‘Psychology of Financial Planning.’” Journal of Financial Planning 38 (9): 66–82.

References

Acierno, Ron, Mara Steedley, Melba A. Hernandez-Tejada, Gabrielle Frook, Jordan Watkins, and Wendy Muzzy. 2020. “Relevance of Perpetrator Identity to Reporting Elder Financial and Emotional Mistreatment.” Journal of Applied Gerontology 39 (2): 221–225.

Anderson, Carol, and Deanna L. Sharpe. 2008. “The Efficacy of Life Planning Communication Tasks in Developing Successful Planner–Client Relationships.” Journal of Financial Planning 21 (6): 66–77.

Anthes, William L., and Shelley A. Lee. 2002. “The Financial Psychology of 4 Life-Changing Events.” Journal of Financial Planning 15 (5): 76–85.

Asebedo, Sarah, and Emily Purdon. 2018. “Planning for Conflict in Client Relationships.” Journal of Financial Planning 31 (10): 48–56.

Benjamin, Michael, and Howard Irving. 2001. “Money and Mediation: Patterns of Conflict in Family Mediation of Financial Matters.” Mediation Quarterly 18 (4): 349–361.

Bertalanffy, Ludwig Von. 1968. General Systems Theory: Foundations, Development and Application. New York: George Brazeller Company.

Biever, Deb Finnegan, Nipa Patel, Ashley Agnew, Daniel Kopp, Jodi Krausman, and Megan A. McCoy. 2021. “When Money Can’t Be Avoided: Helping Money Avoidant Widows Using the Changes and Grief Model.” Journal of Financial Therapy 12 (2): 2.

Britt, Sonya L. 2016. “The Intergenerational Transference of Money Attitudes and Behaviors.” Journal of Consumer Affairs 50 (3): 539–556.

Brown, Brené. 2021. Atlas of the Heart: Mapping Meaningful Connection and the Language of Human Experience. Random House.

Byram, Jamie Lynn, Megan McCoy, Michelle Kruger and John Grable. 2024. Financial Planning Counseling Skills. ALM Global.

Chatterjee, Swarn, and Lu Fan. 2021. “Older Adults’ Life Satisfaction: The Roles of Seeking Financial Advice and Personality Traits.” Journal of Financial Therapy 12 (1): 4.

Dew, Jeffrey P., and Robert Stewart. 2012. “A Financial Issue, a Relationship Issue, or Both? Examining the Predictors of Marital Financial Conflict.” Journal of Financial Therapy 3 (1): 4.

Dubofsky, David, and Lyle Sussman. 2009. “The Changing Role of the Financial Planner Part 1: From Financial Analytics to Coaching and Life Planning.” Journal of Financial Planning 22 (8): 48–57.

Financial Therapy Association. n.d. “Webinars.” Accessed September 27, 2024. https://financialtherapyassociation.org/education/webinars/.

Folberg, Jay. 2009. “Mediating Family Property and Estate Conflicts.” Probate and Property 23: 8–13.

Fortin, Julie, Marlis Jansen, and Bradley T. Klontz. 2020. “Integrating Interpersonal Neurobiology into Financial Planning: Practical Applications to Facilitate Well-being.” Journal of Financial Planning 33 (5): 46–54.

Green, Janice L. 2010. “Late-life Divorce: A Role for Financial Planning.” Journal of Financial Planning 23 (8): 48–53.

Horwitz, Edward J., and Bradley T. Klontz. 2013. “Understanding and Dealing with Client Resistance to Change.” Journal of Financial Planning 26 (11): 27–31.

Kleingeld, Henda. 2023. “Rebuilding a Stable Emotional and Financial Foundation After the Divorce.” In Perspectives in Financial Therapy. Edited by Prince Sarpong and Liezel Alsemgeest. Springer International Publishing: 187–195.

Lawson, Derek, and Brad Klontz. 2017. “Integrating Behavioral Finance, Financial Psychology, and Financial Therapy Into the 6-Step Financial Planning Process.” Journal of Financial Planning 30 (7): 48–55.

Lee, Jennifer C., and Jeylan T. Mortimer. 2009. “Family Socialization, Economic Self-Efficacy, and the Attainment of Financial Independence in Early Adulthood.” Longitudinal and Life Course Studies 1 (1): 45–62.

Lurtz, Meghaan. 2024. “Why ‘Think It Over’ Isn’t Effective for Financial Planning Relationships.” Nerd’s Eye View. www.kitces.com/blog/financial-advisor-sales-tactics-services-discovery-meeting-agenda-think-it-over/.

Lurtz, Meghaan R., Derek T. Tharp, Katherine S. Mielitz, Michael Kitces, and D. Allen Ammerman. 2020. “Decomposing the Gender Divorce Gap Among Personal Financial Planners.” Journal of Family and Economic Issues 41: 19–36.

McCoy, Megan, Ives Machiz, Josh Harris, Christina Lynn, Derek Lawson, and Ashlyn Rollins-Koons. 2022. “The Science of Building Trust and Commitment in Financial Planning: Using Structural Equation Modeling to Examine Antecedents to Trust and Commitment.” Journal of Financial Planning 35 (12): 68–89.

Miller, William R., and Stephen Rollnick. 2012. Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change. Guilford Press.

Naveed, Khurram, Donovan Sanchez, Megan McCoy, and Blake Gray. 2025. “Strengthening Adviser–Academic Connections: Making Financial Planning Research Accessible and Actionable.” Journal of Financial Planning 38 (6): 60–71.

Postmus, Judy L., Gretchen L. Hoge, Jan Breckenridge, Nicola Sharp-Jeffs, and Donna Chung. 2020. “Economic Abuse as an Invisible Form of Domestic Violence: A Multicountry Review.” Trauma, Violence, & Abuse 21 (2): 261–283.

Prochaska, James O., and Carlo C. DiClemente. 1983. “Stages and Processes of Self-Change of Smoking: Toward an Integrative Model of Change.” Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 51 (3): 390.

Salinger, Tobias. 2021. “CFP Board Adds Psychology to Key Study Topics for CE Credits, Exam.” Financial Planning. www.financial-planning.com/news/cfp-board-adds-psychology-to-key-study-topics-for-ce-credits-exam.

Smodic, Shelitha, Emily Forst, John Rauschenberger, and Megan McCoy. 2019. “Financial Planning with Ambiguous Loss from Alzheimer’s Disease: Implications, Applications, and Interventions.” Journal of Financial Planning 32 (8): 34–45.

Tenerelli, David, Sharon Weaver, Nathan Astle, and Megan A. McCoy. 2019. “Scaffolding or Enabling? Implications of Extended Parental Financial Support into Adulthood.” Journal of Financial Therapy 10 (2): 5.

Yeske, Dave. 2016. “A Concise History of the Financial Planning Profession.” Journal of Financial Planning 29 (11): 10–13.