Journal of Financial Planning: March 2022

William Reichenstein, Ph.D., CFA, is the head of research at Social Security Solutions, Inc. (ssanalyzer.com) and Retiree, Inc. (incomesolver.com), which are the leading software products on, respectively, when to claim Social Security benefits and how to tax-efficiently withdraw funds from a financial portfolio in retirement. He has published more than 200 articles and several books, including Social Security Strategies with William Meyer and Income Strategies. He is professor emeritus at Baylor University.

JOIN THE DISCUSSION: Discuss this article with fellow FPA Members through FPA's Knowledge Circles.

FEEDBACK: If you have any questions or comments on this article, please contact the editor HERE.

Financial planners should be aware of opportunities their clients have to redo a prior Social Security claiming decision when such a change would improve their retirement prospects. In Reichenstein and Meyer (2016), I coauthored an article that described then-available Social Security redo strategies. However, some of those strategies are no longer legal. Thus, in this column, I update that discussion by describing four redo strategies that are currently available for Social Security claiming decisions.

In the analysis of competing Social Security claiming strategies in this column, I compare the expected real (i.e., inflation-adjusted) lifetime benefits of competing claiming strategies. Suppose a single individual’s monthly benefits are $2,000 the first year. Since COLAs are designed to keep the (pretax) purchasing power of Social Security benefits constant, the analyses assume a constant real benefit of $2,000 per month for this individual. We find that most clients appreciate this framework.1

Withdrawal of Application

The first of these redo strategies is a withdrawal of application. Consider Jane, a client who lost her job in March 2020 due to the pandemic. Her primary insurance amount (PIA) is $2,400. She was born December 2, 1959. Thus, her full retirement age (FRA) for retirement benefits is 66 years and 10 months. She filed for her benefits at age 62 for December 2021 of $1,700 per month with the first payment due in January 2022. However, in early 2022, she learned that, due to her estimated life expectancy of 90 years, she would increase her expected real lifetime benefits by delaying her Social Security benefits until age 70. Since less than 12 months have passed since she started her benefits, she has the one-time right to redo her prior Social Security claiming decision entirely. To be precise, she can withdraw her application for retirement benefits (i.e., benefits based on her earnings record) through December 31, 2022, that is, through 12 months past her beginning month. If she withdraws her application, then she must pay back all prior benefits based on her earnings record including, if any, spousal or children’s benefits that are based on her record. (An exception is that Jane would not have to repay benefits of an ex-spouse’s spousal benefits if the divorce occurred at least two years prior.) Also, anyone receiving benefits based on Jane’s earnings record (except the ex-spouse described above) must consent in writing to the withdrawal. However, there would be no interest due on those repayments. Using Social Security terminology, Jane may withdraw her claim for retirement benefits by completing SSA-521, Request for Withdrawal of Application. For additional information, see Social Security Administration (2021a).

To understand why this redo strategy may be appropriate, suppose Jane lives to age 90. If she does not withdraw her application, then her lifetime real benefits would be $571,200 [$1,700 per month × 12 months × (90 – 62 years)]. If she withdraws her application and lives to 90, then her lifetime real benefits would be $721,920 [$3,008 per month × 12 months × (90 – 70 years)]. Therefore, by withdrawing her application, Jane can increase her expected real lifetime benefits by $150,720. Furthermore, the higher monthly benefits from delaying the start of benefits until age 70 will continue for the rest of her life. Thus, this withdrawal-of-application strategy would reduce her longevity risk (that is, the risk that she will outlive her financial resources) if she lives longer than expected.

In another example, consider George. He has a PIA of $2,500, FRA of 67, and a short life expectancy of 73. George is married to Pam, who is eight years younger, has a life expectancy of 85, but has no PIA since she has worked little outside the home. Due to his short life expectancy, George begins his benefits at age 62 of $1,750 per month, thinking this would be his best claiming strategy. Later, but before 12 months have passed, someone informs him that starting his benefits early will permanently reduce Jan’s survivor benefits. Based on their life expectancies, benefits based on George’s earnings record will last until Pam dies, when he would have been 93. To maximize their joint lifetime benefits, he should withdraw his application and repay prior benefits. At 70, he should begin his retirement benefits at $3,100 per month [$2,500 × 1.24] before COLAs. The lesson is that, in general, the higher earner should base his or her starting date on the age he or she would be when the second spouse is expected to die. In this example, even though George has a short life expectancy, he should withdraw his application, repay his benefits, and delay his benefits until age 70.

In this example, Pam cannot receive spousal benefits if George files before age 70 because she would not yet be 62. Suppose she was three years younger than George. Then, their lifetime maximizing strategy would be for George to file for retirement benefits at age 69, so Pam can file for spousal benefits at that time. If George files at age 69 instead of 70, Pam gets one more year of spousal benefits, but George’s retirement benefits and Pam’s survivor benefits after his death will be reduced by 8 percent of PIA. In this case, George’s filing age would not only affect his retirement benefits and thus Pam’s survivor benefits, but it would also affect her spousal benefits.

Suspension of Retirement Benefits

This strategy applies to people who began retirement benefits before FRA and more than 12 months have passed since they began benefits. They cannot withdraw their application for benefits as described above. However, they can increase their monthly benefits by suspending their retirement benefits at their FRA or later and restarting their retirement benefits at a later date (probably at 70) to earn delayed retirement credits. When benefits are suspended, prior benefits, including benefits received by a spouse or child based on the earnings record of the person suspending benefits, do not need to be repaid. However, anyone receiving benefits based on the earnings record of the person suspending benefits (except an ex-spouse) will lose those benefits until the suspended benefits have begun anew. Furthermore, the person who suspended their retirement benefits cannot receive spousal benefits during the suspension period. For additional information, see Social Security Administration (2021b). I present one example for a single client and one for a married client.

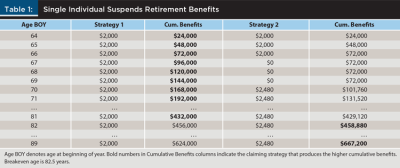

Single

Consider Beth. She is single, has an FRA of 67, and a PIA of $2,500. In Strategy 1 of Table 1, she files for her retirement benefits at age 64 of $2,000 per month [80 percent of $2,500] and continues these benefits until her death. If she dies at age 90, as expected, then her lifetime real benefits will be $624,000 [$2,000 per month × 12 months × (90 – 64 years)].

In Strategy 2, she files for her benefits at 64, but more than 12 months pass since she filed for her retirement benefits. So, she cannot withdraw her application for benefits. However, at her FRA, she could suspend her benefits and refile for her retirement benefits at 70 of $2,480 per month in real terms [$2,000 × 1.24 percent, which reflects three years of delayed retirement credits]. In Strategy 2, she receives real benefits of $2,000 per month from age 64 until 67 plus $2,480 per month from age 70 until 90 for total real benefits of $667,200, which is $43,200 more than her lifetime benefits in Strategy 1. If she lives past age 82.5, then the lifetime benefits in Strategy 2 would exceed her lifetime benefits in Strategy 1.2 As shown in Reichenstein and Meyer (2017), the breakeven age between starting real retirement benefits at FRA or 70 is 82.5 years whether the FRA is 66, 66.5, or 67.

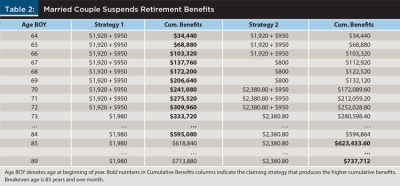

Married

Tom and Judy are a same-age married couple with FRAs for all benefits of 67 years and PIAs of $2,400 and $1,000, respectively. Tom has a short life expectancy of 73, while Judy has a life expectancy of 90. In Strategy 1 in Table 2, they both filed for benefits at age 64. Tom filed for his retirement benefits of $1,920 [80 percent × $2,400] and Judy filed for her retirement plus spousal benefits totaling $950 [retirement benefits of 80 percent of $1,000 plus spousal benefits of 75 percent of ({half of $2,400} – $1,000)]. They continue these benefits until Tom dies at age 73. After his death, Judy receives survivor benefits of $1,980 per month.3

In Strategy 2, as before, they both filed for benefits at age 64. However, at FRA of 67, Tom suspends his retirement benefits. So, for three years, he receives no benefits, while Judy receives her retirement benefits of $800 per month. At 70, Tom resumes his retirement benefits of $2,380.80 per month [$1,920 × 1.24, which reflects three years of delayed retirement credits], and Judy receives her retirement plus spousal benefits of $950 per month.4 When Tom dies at 73, Judy receives survivor benefits of $2,380.80 per month until her death at age 90.

If Judy lives to age 90, then Strategy 2 would provide $23,832 more in real lifetime benefits than Strategy 1. Strategy 2 beats Strategy 1 if Judy lives to at least age 85 and one month. This breakeven age is older than the breakeven age of 82.5 years for Beth for two reasons. First, when Tom suspended his benefits in Strategy 2, Judy lost $150 per month of spousal benefits for three years. Second, Judy’s survivor benefits in Strategy 1 exceeded Tom’s benefits at his death. In short, there are complications that caused this couple’s breakeven age to be older.

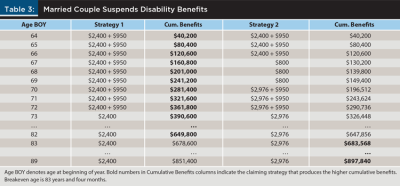

Suspension of Disability Benefits

We now consider a disabled person’s ability to suspend retirement benefits at FRA. Let’s return to the Tom and Judy example, except this time, we assume Tom is disabled. In Strategy 1 in Table 3, Tom and Judy filed for their benefits at age 64. However, Tom receives his PIA of $2,400 per month when he files for disability benefits. Judy receives retirement plus spousal benefits totaling $950 per month. They continue these benefits until Tom dies, at which time Judy continues Tom’s benefits as her survivor benefits.

In Strategy 2, Tom and Judy file for benefits at age 64 and receive the same amounts as in Strategy 1 in the first three years. At FRA, Tom suspends his benefits, which are labeled retirement benefits instead of disability benefits once he attains FRA, and Judy receives her retirement benefits of $800 per month. At 70, Tom resumes his retirement benefits of $2,976 per month [$2,400 × 1.24], and Judy receives her retirement plus spousal benefits of $950 per month. When Tom dies at 73, Judy receives survivor benefits of $2,976 per month until her death at age 90. If Judy lives to at least age 83 and four months, then Strategy 2 beats Strategy 1.

As noted in the example for Beth, the breakeven age for a single individual between beginning retirement benefits at FRA or 70 is 82.5 years. For Tom and Judy in this suspension of disability benefits example, the breakeven age is 83 years and four months. This additional 10 months compared to the 82.5 breakeven age for single Beth is due to Judy’s loss of spousal benefits in Strategy 2 for the three years that Tom’s retirement benefits were suspended.

Filing for Retroactive Benefits

Someone can file for retroactive retirement or spousal benefits up to six months prior if that filing date does not take their beginning benefits date to before their FRA for retirement or spousal benefits. Suppose single Tamara has an FRA of 66 and PIA of $2,800. She was planning to file for benefits at 70. However, due to recent health issues, she now has a much-shortened life expectancy of 72 years. She should apply now, at age 69, for retirement benefits at the level appropriate for age 68 and six months and receive a lump sum check for six months of prior benefits. If she lives to age 72, by filing for retroactive benefits, she would receive real benefits of $3,360 per month [$2,800 × 1.20] from age 69 to 72 plus retroactive benefits of $20,160 [$3,360 per month for six months]. If she files today for her age-69 benefits of $3,472 per month, then these benefits would be expected to last from age 69 to 72. The retroactive strategy is expected to provide $16,128 more in real lifetime benefits. Retroactive filing can be viewed as a redo strategy because it is something different than the usual claiming strategy of filing today for retirement benefits.

Summary

Due to the pandemic, many financial planners will have more clients than usual who filed for their retirement benefits sooner than they now wish that they had filed. In this column, I explained steps these clients can take now to either (1) completely offset a prior claiming decision in the case of a withdrawal of application or (2) partially offset a prior claiming decision in the case a suspension of benefits. In addition, I explain how someone older than their FRA can file for retroactive benefits up to six months prior as long as that filing date does not take their beginning benefits date to before their FRA. By applying these redo strategies, financial planners can add value to their clients’ retirement resources.

Endnotes

- Another framework for selecting a Social Security claiming strategy is to select the strategy that maximizes the present value of lifetime benefits. In this column, I adopt the strategy of maximizing real lifetime benefits; that is, I assume a real discount rate of 0 percent. As of December 2021, the real yield on 10-year Treasury Inflation Protection Security bonds was –1 percent. This exceptionally low real rate encourages selecting the claiming strategy that maximizes the age-70 retirement benefits even more than the maximizing-real-lifetime-benefits strategy that I adopt in this paper. I made this choice because I expect the –1 percent real rate to be a relatively short-lived phenomenon.

- In both strategies, Beth receives $2,000 per month from age 64 until 67. If she does not suspend her benefits, then her other cumulative real benefits are $2,000 per month × 12 months × ( X – 67 years), where X is her age at death. If she suspends her benefits, then her other cumulative real benefits are $2,480 per month × 12 months × (X – 70 years), where X is her age at death. These two amounts are equal if she lives to age 82.5.

- Since Judy begins survivor benefits after attaining her FRA for survivor benefits, she gets the larger of (1) Tom’s $1,920 monthly real benefit level at his death or (2) 82.5 percent of his PIA, which is $1,980.

- Tom’s real benefits level is $2,380.80 per month, but his nominal benefits level would be higher due to COLAs. In practice, the Social Security Administration rounds nominal benefits down to the whole dollar. Since COLAs are unknown, I do not round down this real benefits level.

References

Reichenstein, William, and William Meyer. 2016. “Redo Strategies: When Can You Redo a Prior Social Security Claiming Decision?” Journal of Financial Planning 29 (6): 48–53.

Reichenstein, William, and William Meyer. 2017. Social Security Strategies, 3rd ed.

Social Security Administration. 2021a. “Retirement Benefits: Withdrawing Your Social Security Retirement Application.” www.ssa.gov/planners/retire/withdrawal.html.

Social Security Administration. 2021b. “Retirement Benefits: Suspending Retirement Benefit Payments.” www.ssa.gov/planners/retire/suspend.html.