Journal of Financial Planning: June 2016

William Reichenstein, Ph.D., CFA, is the Pat and Thomas R. Powers professor of investments at Baylor University. He is head of research at Social Security Solutions Inc., which develops software for financial advisers to help clients decide when to claim Social Security benefits (www.ssanalyzer.com). He is also head of research at the software firm, Retiree Income Inc.

William Meyer is CEO of Social Security Solutions Inc. and Retiree Income Inc. Retiree Income is the developer of Income Solver (www.incomesolver.com), software that provides advice on how taxpayers can maximize the longevity of their financial portfolio through tax-efficient retirement withdrawals.

Executive Summary

- Many financial planners are aware that a client has the one-time right to withdraw his or her application for retirement benefits if made within 12 months after benefits began. This article explains two other redo strategies that planners may not be aware of.

- One strategy is the ability to suspend retirement benefits at full retirement age (FRA) or later in order to earn delayed retirement credits, and then to reinstate suspended benefits at a later date.

- The second strategy applies to disabled individuals where the disabled person begins disability benefits before attaining FRA then suspends disability benefits at FRA in order to earn delayed retirement credits.

- Prior to the passage of the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015, other redo strategies were available, however changes embedded in this Act eliminated these other strategies as of April 29, 2016. This article discusses these recent rule changes, explaining that there are now three sets of rules, noting which set of rules apply to individuals, depending upon when they were born.

Financial planners should be aware of opportunities their clients have to redo a prior Social Security claiming decision when such a change would improve their retirement prospects.

One reason a client may wish to redo a prior decision is a change in personal circumstances. For example, a single individual with a long life expectancy may begin Social Security benefits when she retires at age 63, but later learn that she could maximize her expected lifetime benefits by delaying her starting date until age 70. In another example, she may have begun benefits at 63 after being laid off, but then returns to full-time work. In both examples, if less than 12 months have passed since she started benefits, she can redo her prior decision entirely. If more than 12 months have passed, she can still suspend her benefits at full retirement age (FRA), which will allow her to earn delayed retirement credits, and therefore partially redo her prior claiming decision.

In this study, three strategies for redoing a client’s prior Social Security claiming decision are explained. For each strategy, the appropriate Social Security terminology is presented so your client can effectively communicate with Social Security Administration (SSA) personnel.

The three basic redo strategies are:

- The one-time right to withdraw an application for retirement benefits if done within 12 months of beginning benefits.

- The right to suspend retirement benefits at FRA or later to earn delayed retirement credits.

- The right to suspend disability benefits at FRA or later to earn delayed retirement credits.

Separately, the Bipartisan Budget Act

of 2015 includes significant changes to Social Security rules. The next section explains these rule changes and discusses their significance.

Social Security Rule Changes in the 2015 Budget Act

The Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015 passed into law the first significant Social Security rule changes since 2000. There are now three separate sets of rules that apply to individuals, depending upon when they were born. Congress has the right to change Social Security rules at any time; the redo strategies described here are based on current Social Security rules.

The 2015 Act eliminated two Social Security claiming strategies for some individuals—the file-and-suspend strategy, and the strategy of filing a restricted application for one type of benefit only. The Act did, however, include two windows for certain individuals to take advantage of the older rules. In doing so, the law segmented people into one of three age groups:

Group 1: those born on April 30, 1950 or earlier and will therefore attain FRA by April 29, 2016, the end of the implementation period. (Social Security considers people to “attain” an age one calendar day prior to their actual birthday.)

Group 2: those born between May 1, 1950 and January 1, 1954 and therefore “attained” age 62 by the end of 2015.

Group 3: those born on January 2, 1954 or later and therefore did not “attain” age 62 by the end of 2015.

Here is a summary of the recent Social Security rule changes and the groups to which each change applies.

File-and-suspend strategy. The file-and-suspend strategy is available to individuals in Group 1, so long as they filed and suspended their benefits by April 29, 2016. The file-and-suspend strategy is not available to individuals in Groups 2 or 3.

In a file-and-suspend strategy, one spouse (assumed male for clarity) files for his benefits and immediately suspends them at or after attaining his FRA. This allows his wife, if she is at least full retirement age and in Group 1 or 2, to file a restricted application for spousal benefits. Later, usually at age 70, he begins his retirement benefits, which includes delayed retirement credits, and she switches to her retirement benefits if they exceed her spousal benefits.

Restricted application strategy. Filing a restricted application is a strategy that can be used by individuals in Groups 1 and 2, but Group 3 individuals cannot file a restricted application.

In a restricted application, someone files for one type of benefit—usually spousal benefits—and later, usually at age 70, switches to his or her higher retirement benefits, which would include delayed retirement credits. To file a restricted application, a person must: (1) have attained full retirement age; and (2) their spouse must have already filed for his or her retirement benefits.

For example, suppose Jake was born on January 2, 1952. He is 64 years old, has a FRA of 66, is a member of Group 2, and has a primary insurance amount (PIA) of $2,000. PIA is the amount of monthly benefits he would receive if he begins his retirement benefits at his full retirement age.

Jane, his wife, was born on February 2, 1957. She is 59 years old, has a FRA of 66.5, and has a PIA of $800. If Jane applies for benefits at age 62, then Jake can make a restricted application for spousal benefits of $400 (half of her PIA) at that time when he is 67 years and one month old.

At age 70, Jake could switch to his benefits of $2,640 (before cost-of-living adjustments, or COLAs, per month), which would include four years of delayed retirement credits of 8 percent per year. Notice, however, that Jake must wait until Jane files for her retirement benefits before he can file the restricted application for spousal benefits. He was not eligible for spousal benefits at his FRA, because Jane had not yet begun her retirement benefits. Furthermore, if Jane delays her benefits until Jake turns 70, then Jake would not receive spousal benefits.

This example illustrates that the new rules often encourage the younger spouse to file for benefits as soon as possible so the older spouse can receive spousal benefits for the longest period of time. If the death of the first spouse occurs after Jake turns 70—and it does not matter which spouse dies first—then the surviving spouse will continue to receive $2,640 (before COLAs).

Deemed filing. Once again, those in Group 3 are forbidden from filing a restricted application for benefits. That is, they cannot file for one type of benefit at full retirement age and then switch to another benefit at a later date.

Prior to the 2015 Act, anyone applying for benefits before attaining full retirement age was “deemed” to be applying for their retirement benefits plus, if eligible, spousal benefits. However, if they filed for benefits at FRA or later, then they could have filed a restricted application for one type of benefit. After passage of the Act, Group 3 individuals are “deemed” to be applying for their own retirement benefits plus, if eligible, spousal benefits whenever benefits are applied for. Stated differently: they cannot file a restricted application for only one type of benefit.

One-Time Right to Withdrawal

The first strategy describes a client’s one-time right to withdraw his or her application for retirement benefits if made within 12 months after benefits began. This is the one redo strategy many financial planners are aware of. Here is an example to illustrate this strategy:

Joe will turn 62 on November 2, 2016. In September 2016, he tells the Social Security Administration that he wants to begin his retirement benefits for November 2016 with the first payment received in December 2016. He may redo this decision in the first year. Each person can use this redo strategy one time if the withdrawal of application is made within 12 months after benefits began.

If he withdraws his application, then he must pay back all prior benefits based on his earnings record including, if any, spousal or children’s benefits that are based on his record. An exception is that Joe does not have to repay benefits of an ex-spouse’s spousal benefits if the divorce occurred at least two years prior. Also, anyone receiving benefits based on Joe’s earnings record (except the ex-spouse described above) must consent in writing to the withdrawal. However, there would be no interest due on those repayments.

Using Social Security terminology, Joe may withdraw his claim for retirement benefits by completing Form SSA-521, Request for Withdrawal of Application. In this example, because he is first entitled to benefits for November 2016, he must withdraw his application by November 30, 2017.1 For additional information, see the Social Security Administration’s “Retirement Planner: If You Change Your Mind” at www.ssa.gov/planners/retire/withdrawal.html.

To understand why this redo strategy may be appropriate, suppose Joe is single and has a life expectancy of 86 years, a primary insurance amount (PIA) of $2,500, and he started his benefits at $1,875 per month at age 62 within the past 12 months. Since starting his benefits, he learned that he could increase his expected lifetime benefits by withdrawing his application and applying for benefits anew at a later date.

If he continues his current age-62 benefits, the expected purchasing power of his lifetime benefits in today’s dollars would be $540,000, [0.75 x $2,500, or $1,875 per month x 12 months x 24 years from age 62 to 86]. Each year, nominal benefits will increase with the inflation rate, but so will prices, so the purchasing power of these monthly benefits will remain constant when expressed in today’s dollars.2,3

If he repays his age-62 benefits within 12 months and delays his retirement benefits until age 66 or 70, his expected lifetime benefits would increase to $600,000, [$2,500 per month x 12 months x 20 years], or $633,600, [1.32 x $2,500, or $3,300 per month x 12 months x 16 years].

These age-66 and age-70 amounts are $60,000 and $93,600 larger than the age-62 expected lifetime benefit. In addition, based on current Social Security promises, Joe cannot outlive the higher monthly benefits from delaying his benefits until age 66 or 70. So, if Joe lives longer than expected, this withdrawal of application strategy would provide more monthly income for the rest of his life, thus reducing his longevity risk. Obviously, in this example, Joe must have the resources to repay the up to 12 months of benefits beginning at age 62.

In another example, consider George. He has a PIA of $2,500 and a short life expectancy of 73. George is married to Jan, who is eight years younger, has a life expectancy of 85, but has no PIA because she has worked little outside the home. Because of his short life expectancy, George began his benefits of $1,875 per month at age 62, thinking this would be his best claiming strategy. Later, but before 12 months have passed, someone informs him that starting his benefits early will permanently reduce Jan’s survivor benefits. Based on their life expectancies, benefits based on George’s earnings record will last until Jan dies (when he would have been 93 if still alive). To maximize their joint lifetime benefits, he should withdraw his application and repay prior benefits. At 70, he should begin his benefits at $3,300 per month before COLAs, [$2,500 x 1.32].

The lesson is: in general, the higher earner should base his or her starting date on the age he or she would be when the second spouse is expected to die. In this example, even though George has a short life expectancy, he should withdraw his application, repay his benefits, and delay his benefits until age 70.

Suspend Retirement Benefits at FRA or Later

The second strategy applies to someone who began retirement benefits before FRA and more than 12 months has passed since benefits started. He or she wants to increase his or her monthly benefit amount by delaying benefits, thereby earning delayed retirement credits. Here is an example:

Betty is single, retired, and has a FRA of 66. She began her Social Security retirement benefits 15 months ago at age 63 when her benefits were 80 percent of her primary insurance amount. She has a long life expectancy.

After beginning her benefits, she learns that she would maximize her expected lifetime benefits by delaying the start of her benefits for as long as possible. Because more than one year has passed since she began her benefits, the withdrawal of application strategy discussed earlier is not an option. However, at her FRA, she could suspend her benefits. At a later date (but by age 70), she could reinstate her suspended benefits.

If she reinstates her benefits at age 70, she would get 105.6 percent of her PIA [80 percent x 1.32 = 105.6 percent], where 1.32 denotes the 32 percent delayed retirement credit for suspending her benefits from age 66 to 70. This 32 percent reflects four years of delayed retirement credits at 8 percent (non-compounded) per year of delay. When benefits are suspended, prior benefits—including benefits received by a spouse or child based on the earnings record of the person suspending benefits—do not need to be repaid.

However, due to the Budget Act of 2015, if she suspends her benefits, anyone (except her ex-spouse) receiving benefits based on her earnings record would lose those benefits until she begins her benefits anew.

To be precise, Group 1 individuals who filed and suspended their benefits by April 29, 2016 could still have others receive benefits based on their record. However, Group 1 individuals who suspend their benefits after April 29, 2016 cannot have others (except their ex-spouses) receive benefits based on their record until they begin their benefits anew.

Group 2 and 3 individuals can suspend their benefits at full retirement age or later to earn delayed retirement credits, but because this would be after April 29, 2016, anyone receiving benefits based on their earnings record (except their ex-spouses) will lose those benefits until the suspended benefits have begun anew. For additional information, see the Social Security Administration’s “Retirement Planner: Suspending Retirement Benefit Payments,” at www.ssa.gov/planners/retire/suspend.html.

In this example, Betty’s monthly benefits after reinstating her suspended benefits at age 70 would be 32 percent higher than her monthly benefit level from starting benefits at age 63. If Betty lives beyond age 82.5, then her cumulative lifetime benefits in today’s dollars—if she suspends her benefits at age 66 and reinstates them at age 70—would be higher than her lifetime benefits if she simply continued her benefits.4

Moreover, most retirees are concerned about running out of money. By suspending her benefits from FRA to age 70, she is assured a monthly benefit level that is 32 percent higher than if she simply continued her monthly benefits at her age-63 benefit level. Based on current promises of the Social Security system, she cannot outlive this additional 32 percent in monthly benefits.

Suspend Disability Benefits at FRA or Later

The third strategy pertains to someone receiving Social Security disability benefits before his or her full retirement age. Here are two examples: one for a single individual and one for a married couple.

Single individual. Nancy is 64 years old and begins disability benefits of $2,000 per month, her primary insurance amount. At her FRA of 66, she could continue to receive $2,000 (before COLAs), where the disability benefit automatically becomes her retirement benefit at her FRA. Alternatively, she could suspend her benefits at FRA and, at age 70, she could begin her retirement benefits at $2,640 (ignoring COLAs). The breakeven age for this decision is about 82.5.5 She is otherwise healthy and comes from long-lived parents and grandparents, so she selects the latter strategy.

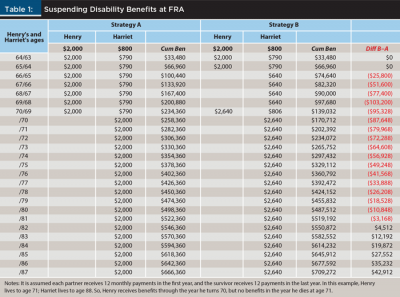

Married couple. Consider Henry and Harriet Smith. Henry was just ruled to be disabled. He is 64 years old, has a PIA of $2,000, but because of his disability, he has a short life expectancy of 71. Harriet, his wife, is 63, has a PIA of $800, and a life expectancy of 88. FRA for all benefits for both spouses is 66. Table 1 presents the cash flows from two of their claiming strategies with cash flows expressed before COLAs.

In Strategy A, Henry files for disability benefits today. Because he is disabled, he receives $2,000 per month, his PIA. Harriet files today for her own retirement benefits and her spousal benefits. Because she applies for retirement benefits before FRA and Henry has begun disability benefits, she is deemed to be applying for both her retirement benefits and spousal benefits. She is age 63, so she receives retirement benefits of $640, [0.8 ($800)], plus spousal benefits of $150 [0.75 ($1,000 – $800)], for total benefits of $790, where 0.8 reflects the reduction to her retirement benefits and 0.75 reflects the spousal benefit fraction for beginning these benefits 36 months before her FRA. At Henry’s FRA, his disability benefit automatically converts to a retirement benefit at the same level. After Henry’s death at age 71, Harriet switches to survivor benefits of $2,000 per month.

In Strategy B, Henry files for disability benefits today of $2,000 per month, and Harriet files today for her own retirement benefits plus spousal benefits of $790 per month. At FRA, Henry suspends his retirement benefit application, and thus Harriet loses her spousal benefits. She continues to receive her retirement benefits of $640. At age 70, Henry resumes his retirement benefits of $2,640 per month, and Harriet adds spousal benefits of $166 for total benefits of $806 per month. This higher amount reflects a spousal benefit fraction of 0.8333, which is higher than 0.75 because she did not get spousal benefits for one year from age 65 to 66. After Henry’s death at age 71, Harriet switches to survivor benefits of $2,640 per month.

Table 1 shows these monthly cash flows. The cumulative benefits columns (labeled “Cum Ben”) depict their joint cumulative benefits from these two strategies (assuming they receive 12 benefit payments in the first and last year).

The “Diff B–A” column shows that Strategy B provides the larger joint benefits if Harriet lives to at least 82 years and five months, (that is, five months into her 83rd year). Despite Henry’s short life expectancy, he might elect to suspend his retirement benefit at FRA so his wife could receive a larger survivor benefit after his death. This is considered a redo strategy because at his FRA, he must take the initiative to suspend his retirement benefits.

For more information on claiming strategies when one spouse receives disability benefits or one spouse suddenly has a greatly reduced life expectancy, see Meyer and Reichenstein (2014).

Conclusion

This article presented three strategies where someone can redo a prior Social Security claiming decision. The first strategy is the one-time right of a claimant to withdraw his or her application for retirement benefits if made within 12 months after benefits began. Many financial planners are aware of this redo option.

Perhaps a lesser-known strategy is the ability to suspend retirement benefits at FRA or later in order to earn delayed retirement credits, and then to reinstate suspended benefits at a later date. When the withdrawal of application strategy is not available because more than 12 months have passed since benefits began, then the ability to suspend benefits at FRA or later is usually a useful partial redo strategy. That is, even though the claimant cannot completely redo the initial claiming strategy, he or she can still partially redo this strategy by suspending benefits at FRA and then delaying benefits until age 70.

Another lesser-known strategy among financial planners applies to disabled individuals who begin disability benefits before attaining FRA. When the disabled individual turns full retirement age, he can suspend his benefits in order to receive delayed retirement credits. Later, typically at age 70, he would restart his suspended benefits.

Social Security claiming strategies are complex. Clients can leave $100,000 or more on the table by making uninformed claiming decisions. This article discussed ways clients may be able to redo or, at least partially redo, a prior claiming decision and presented examples showing why it may be to their advantage to do so.

Endnotes

- In this example, to be entitled to benefits, Joe must be eligible for benefits and apply for benefits. If he does not file for benefits, he would be eligible for benefits but not entitled to benefits. As discussed in Reichenstein and Meyer (2015), the first month someone is eligible for benefits is the first month he or she has attained age 62 for the entire month. Social Security considers someone to attain an age one day before his or her birthday. Therefore, Joe, who was born on November 2, is eligible for benefits for November 2016, because he would have attained age 62 for all of that month.

- These purchasing-power-of-lifetime-benefit amounts if benefits begin at 62, 66, or 70 are also the approximate present values of expected lifetime benefits. As explained in Reichenstein and Meyer (2015), since late 2008 the real (inflation-adjusted) yield on 12-year Treasury Inflation Protection Securities (TIPS) has been about 0 percent. The appropriate discount rate for calculating present values is the rate of return investors can earn on similar-risk securities. There is wide agreement that a TIPS bond is the security with risk most like that of Social Security benefits. Cash flows on both TIPS bonds and Social Security are promises of the federal government that are linked to inflation. Thus, Social Security real benefit levels should be discounted by the real yield on TIPS bonds with the same duration as projected Social Security benefits. The duration of a 12-year TIPS bond with a 0 percent real yield is the same as the duration of a 24-year (for example, age 62 to 86) Social Security stream of benefits with annual COLAs, and the life expectancy of a 62 year old is about 86 today. So, the duration-appropriate TIPS bond in this example has a maturity of about 12 years.

- Today, with real Treasury yields near 0 percent, the breakeven period between starting benefits at age 62 or full retirement age of 66 is about 78 years, while the breakeven age between starting benefits at age 62 and 70 is about 80.5 years. See Endnotes 4 and 5 for examples of how to calculate a breakeven age.

- Today she is full retirement age (age 66). If she continued her benefits at 80 percent of PIA and lives X more years, then her future lifetime benefits in today’s dollars would be 0.80 x PIA x X years x 12 months/year. If she suspends her benefits at age 66 and reinstates them at age 70, her lifetime benefits in today’s dollars would be 1.056 x PIA x X–4 x 12. Setting the two to be equal produces a breakeven point of 16.5 years from today (and remember she is 66 years old), so the breakeven age is 82.5.

- Today she is full retirement age (age 66). If she continued her benefits of $2,000 per month and lives X more years, then her future lifetime benefits in today’s dollars would be $2,000 x X years x 12 months/year. If she suspends her benefits at age 66 and reinstates them at age 70, her lifetime benefits in today’s dollars would be $2,640 x X–4 x 12. Setting the two to be equal produces a breakeven point of 16.5 years from today (and she is 66 years old), so the breakeven age is 82.5.

References

Meyer, William and William Reichenstein. 2014. “Greatly Reduced Life Expectancy: How Should It Affect a Couple’s Social Security Claiming Strategy?” Journal of Financial Service Professionals 68 (1): 39–52.

Reichenstein, William and William Meyer. 2015. Social Security Strategies: How to Optimize Retirement Benefits, 2nd Edition.

Citation

Reichenstein, William, and William Meyer. 2016. “Redo Strategies: When Can You Redo a Prior Social Security Claiming Decision?” Journal of Financial Planning 29 (6): 48–53.