Journal of Financial Planning: June 2023

Executive Summary

- Leaving wealth to the next generation involves income taxes—in many cases, more than estate taxes. Assigning different beneficiary percentages across accounts can potentially increase the after-tax legacy.

- Executing this beneficiary designation strategy, in coordination with estate documents, should include careful planning, a willingness to revisit assumptions, and evaluation of your client’s desires—including a view on “fairness.”

- Two major unknowns make this task challenging: future tax rates for beneficiaries and future values of different assets. These may be addressed both with conservative assumptions up front and regular estate plan reviews.

- The potential benefit of this strategy depends largely on the gap between beneficiaries’ expected income tax rates and the mix of assets.

- Analysis shows that when tax-deferred assets represent 30 percent to 70 percent of an estate, and beneficiaries have marginal tax rates that differ by at least 10 percent, this strategy can improve total after-tax inheritance by up to 10 percent.

- Determining favorable percentage splits for two beneficiaries is relatively easy; it becomes more challenging with more than two.

- Wills and trust documents can be written with a provision to “equalize” bequests in coordination with assets that pass by beneficiary designations. That provision requires language to value tax-deferred accounts such as individual retirement accounts (IRAs). The assumed tax rate(s) in that language must be carefully determined.

Roger Young, CFP®, is a vice president and thought leadership director with T. Rowe Price Advisory Services Inc. He earned a master’s degree in manufacturing and operations systems from Carnegie Mellon University, a master’s degree in operations research and statistics from the University of Maryland, and a bachelor’s degree in accounting from Loyola University Maryland.

Acknowledgement: The author thanks Sudipto Banerjee and James DiLellio for their valuable comments on the paper.

JOIN THE DISCUSSION: Discuss this article with fellow FPA Members through FPA's Knowledge Circles.

FEEDBACK: If you have any questions or comments on this article, please contact the editor HERE.

NOTE: Click on the images below for PDF versions.

Three developments have made income taxes for beneficiaries increasingly important, relative to estate taxes, in recent decades. The first is a broad trend: Tax-deferred retirement accounts, such as 401(k) plans and traditional IRAs, have grown dramatically. In contrast, defined benefit pensions (which don’t usually pass to the next generation) have declined in popularity.

The other two developments relate to legislative changes. Estate taxes are only relevant to a small fraction of households due to the sharp increase in the federal exclusion. In addition, the SECURE Act of 20191 generally eliminated the ability to stretch IRA distributions over a beneficiary’s expected lifetime, which potentially increases the tax rate paid on those distributions.

If a person’s beneficiaries will likely have significantly different marginal tax rates, it would increase the after-tax value if lower-rate beneficiaries received more tax-deferred assets, and higher-rate beneficiaries received more tax-free assets. Typically, tax-deferred assets, such as retirement accounts, are passed via beneficiary designations (outside the will), whereas investments passed via estate documents may be tax-free due to the step-up in basis.

Implementing an after-tax estate planning strategy, however, has several challenges. First, the percentage allocations to specify in beneficiary designations for each account are not always obvious. Second, those designations need to be coordinated with provisions in a will or trust that govern how other assets are passed.

After initial implementation, the strategy needs to be maintained over time, requiring a plan with flexibility. That way, the plan can still work as intended if beneficiary tax rates and asset values are different from assumptions made in the estate planning process. The estate plan should also be reviewed regularly, a step that unfortunately many people fail to take.

Note that for simplicity, this paper will generally refer to wills (not trusts). It will also describe the investor and beneficiaries as a parent and children, respectively. The beneficiary designations being discussed would typically be contingent beneficiaries for a couple, or primary beneficiaries for a single person or surviving spouse.

Literature Review

This topic has not received much attention from financial planning researchers. The concept of children with different tax rates was discussed briefly by Potts and Reichenstein (2015). They describe a two-beneficiary situation with only tax-deferred and tax-exempt assets, not a taxable account. They assume the goal is to both maximize and equalize the after-tax inheritance.

Similarly, Vnak (2019) proposed equalizing after-tax inheritance via beneficiary designations. He also discussed several practical planning considerations and used a three-beneficiary example.

Young (2020) discussed this strategy as one to consider when deciding whether to shift future retirement savings from pretax to Roth accounts. He observed that using the strategy could reduce the urgency to build Roth balances but did not focus on implementing the strategy.

This study builds upon previous research in two main ways. First, it considers the practical aspects of estate planning, and how beneficiary designations fit into those plans. Before evaluating any numbers, it reconsiders whether equalizing after-tax inheritances will (or should) be considered fair by parents and their adult children. Another practical aspect reflected in the study is how estate attorneys actually implement this type of strategy in wills.

Second, the study develops a framework for implementing the strategy and analyzing the benefits. That framework naturally includes the calculation of percentages allocated to different beneficiaries, by account type. It also identifies another key factor: the assumed tax rate(s) used in a will to value tax-deferred assets, to equalize inheritances across beneficiaries. The framework considers risks posed by changes that can occur between development of an estate plan and the time of execution. Based on the framework, the dollar benefit of the strategy is calculated and analyzed for a wide variety of scenarios.

Combining the practical aspects and analytical framework, the study concludes with guidance on use of the strategy, including when it may be worth the effort and risks.

What Is ‘Fair’?

Before describing the framework and study design, it is important to address the objective of a tax-aware estate strategy.

Potts and Reichenstein, as well as Vnak, point out that a common approach—apportioning the face value of all assets equally, without regard to income taxes—can result in inequal after-tax values to the beneficiaries. If there are any tax-deferred assets (subject to income tax for beneficiaries), a beneficiary with a higher marginal tax rate will receive less, after taxes, than other beneficiaries. Vnak suggests that “this does not align with the parents’ intent” to divide assets equally. Potts and Reichenstein similarly assume parents want children to receive the same amounts after taxes.

Vnak’s proposed solution is to allocate taxable and IRA assets differently to equalize after-tax inheritance and reduce taxes paid. However, in Vnak’s illustration of that solution, the beneficiary in the lowest tax bracket actually receives less after taxes than he would have received under the common approach of equal pretax division!

Imagine being the low-income sibling in that situation. The executor shows you the numbers, and you figure out that you’re getting less under this strategy so your wealthy sibling can save money on taxes. You would probably consider that solution unfair. That could easily lead to unintended bitterness.

Someone’s view of fairness in this situation may depend on their philosophy about our progressive tax system. Some people may also think about whether it’s “fair” that, say, the corporate executive child makes so much more money than the child who’s a teacher in the first place. All of that said, several estate attorneys2 have suggested that, for family harmony purposes, it is usually advisable to divide the money equally, regardless of income disparities. If you aren’t trying to compensate for income disparities, compensating for tax rate disparities on that income seems counter to the goal.

Therefore, this study starts with the premise that equal pretax division of assets will be considered fair by most parents and children. It’s easy to explain, and estate attorneys generally find that people don’t complain about that approach.

Solutions suggested by this study will obviously be intended to reduce overall taxes. But these solutions will be designed so they do not reduce after-tax inheritance for any beneficiary, compared with equal pretax division across assets. A key objective here is “do no harm.” Put another way, this study focuses on improving after-tax inheritance for everyone (from a “fair” starting point), not equalizing after-tax inheritances.

While this study uses a reasonable definition of fairness, it is important to recognize that people can have different views and that the perception of fairness can change over time. This study will not assume that there is one right answer on how to fairly apportion those savings. For example, it could be reasonable (or necessary) to allow one child to get more of the after-tax improvement as long as everyone benefits to some degree.

Hypothetical Case Study of Fairness: A Two-Beneficiary Example

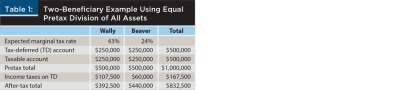

For a simple illustration, consider a situation where a parent’s estate is expected to be $1 million, evenly split between a taxable account and a tax-deferred account. There are two children, one with an expected 43 percent marginal income tax rate (federal and state), the other with a 24 percent marginal rate. The taxable account receives a full step-up in basis at death, so there are no income taxes on that portion of the inheritance.

If the parent divides both accounts equally (before taxes), the distribution is as follows:

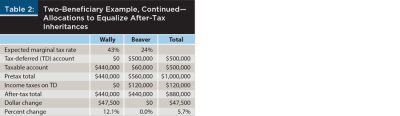

Clearly, total taxes would be lower if Beaver receives all of the tax-deferred account and Wally gets most of the taxable account. If the goal was to equalize after-tax inheritance, the distribution would look like this:

There are several concerns with this approach. First, and most glaring, is that Wally gets all of the incremental benefit. It doesn’t technically violate the “do no harm” rule, but Beaver has no reason to be excited about this “improvement” over the simpler approach.

The second concern involves implementation and sensitivity to changes in the situation. Estate documents need a way to apportion the taxable account to ensure equitable treatment. Unfortunately, specifying a dollar split (like above) is impractical because the value is uncertain. A percentage split (88 percent and 12 percent in this case) would be inequitable if the values turned out to be different. Wally would ultimately receive too much if the taxable account grew and too little if it shrank. A different method is discussed in the next two sections.

Similarly, if the projected tax rates turn out to be incorrect, one of the brothers could be worse off after taxes than under the equal pretax division method. For example, suppose all assumptions were correct, except that Beaver’s tax rate turned out to be 28 percent instead of 24 percent. That four-point change costs him $20,000 after taxes if he gets 100 percent of the tax-deferred account but only $10,000 if all assets were divided equally (as in Table 1). He would be worse off, which violates the “do no harm” principle.

An Approach to Fairness Used by Estate Attorneys

A few estate attorneys shared how they handle real-life situations where non-probate assets are divided unequally (see endnote 2). The method essentially has three steps:

- The value of all assets that are passed outside of the will is added to the probate asset value to arrive at an “adjusted estate” value. Importantly, tax-deferred account values are modified to reflect expected income taxes.

- The adjusted estate value is divided by the number of beneficiaries (assuming the intent to divide assets equally).

- For each child, that share of the adjusted estate is reduced by assets received outside the will (modified for expected taxes as in the first step). The resulting amount is that child’s share of actual probate assets.

This raises a key question: How do attorneys or planners specify the tax rate when modifying non-probate asset values in the first step?

Theoretically, they could assign different tax rates for each beneficiary. However, basing them on expected marginal rates would result in the same division of assets as in Table 2, with some of the same drawbacks. Alternatively, the attorneys could specify that the tax rates should be determined by the executor based on actual or expected tax rates after the parent’s death. That can be challenging and risky for an executor, which is not appealing to estate attorneys. And while that would eliminate the risk of changing tax rates, using multiple rates would still result in one beneficiary getting all of the tax savings, as is illustrated in Table 2.

A Conceptual Framework for a Two-Beneficiary Scenario

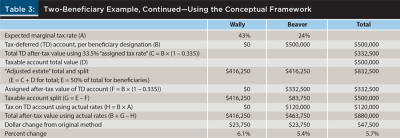

This study’s framework starts with the assignment of a tax rate in the first step above. It builds on a method that appears to be used in practice (see endnote 2): select one tax rate and apply it for all beneficiaries in the calculation. Continuing the example above, Table 3 shows how the distribution would play out using an “assigned tax rate” of 33.5 percent—the midpoint of the two beneficiaries’ projected rates.

There are some appealing features to this framework. First, you will notice that by using an assigned tax rate, a parent can allow both children to benefit from the strategy. From a communication standpoint, this may also make the conversation with children easier—the calculation is the same for everyone, which is, in a sense, fair. And showing how it should benefit everyone certainly helps make the case that a novel approach is worth the effort.

One should keep in mind that there are reasons a parent may want or need to split the improvement unequally. (Examples will be discussed later in the paper.) Different assigned tax rates can enable this while still improving after-tax results for everyone. The key to remember: the higher the assigned rate, the more benefit that goes to the lower-rate3 child.

At one extreme, where the assigned rate equals the higher-rate child’s rate, that child gets no benefit. At the opposite end, assigning the rate at the lower-rate child’s rate means that child gets no benefit. (That is essentially what happens in Table 2.)

The split of the benefit can be determined with a simple calculation:

portion of benefit to lower-rate child =

(assigned rate – rate for lower-rate child) ÷

(rate for higher-rate child – rate for lower-rate child)

In the example above, if the assigned rate was 38.25 percent (75 percent of the way between 24 percent and 43 percent), the lower-rate child, Beaver, gets 75 percent of the benefit.

The framework accounts for potential changes in circumstances, as described in the next section. The determination of percentage splits in beneficiary designations is discussed in the subsequent section on testing.

Anticipating Changes

As noted earlier, beneficiary tax rates and asset values can change. Therefore, beneficiary designations and assigned tax rates should be determined in a manner likely to prevent problems across a reasonable range of scenarios.

Tax Rate Changes

There are many life changes that can affect someone’s marginal tax bracket, including career, marital status, retirement, state of residency, etc., not to mention statutory changes. For example, just moving one tax bracket (e.g., between the 12 percent and 22 percent federal rates) or changing residency (e.g., California to Texas) can have a large impact.

The strategy fails to improve results if the higher-rate child’s marginal rate falls below the assigned rate or the lower-rate child’s marginal rate ends up above the assigned rate. That is consistent with the formula above for the split of the strategy’s benefits. Therefore, to mitigate the risk of harming any beneficiary, consider these steps:

- Wait to implement this strategy until the beneficiaries are relatively settled tax-wise.

- Discuss the plan with all beneficiaries, both for buy-in and to reasonably understand their tax situations.

- Only implement the strategy if there is a significant difference in beneficiaries’ expected tax rates.

- Set the assigned tax rate near the midpoint of the two expected marginal rates—or at least one bracket away from each beneficiary’s expected rate.

- Execute the beneficiary designations and estate documents at the same time. (Estate attorneys say this is often the hardest part!)

- Revisit the plan anytime a beneficiary has a major life event. This might be implemented just by changing beneficiary designations but could also require a change to the assigned tax rate in the will. (The attorneys who were consulted on this topic advocate updating estate plans every five years; they also recognize that most people don’t do it.)

Changes in Asset Values

This strategy relies on having some assets that pass via the will—not just assets with beneficiary designations. Those probate assets, such as taxable accounts, enable the equalization described above in the approach used by estate attorneys.

If a taxable account represents a higher proportion of total assets at death than expected, that doesn’t present a problem. However, if taxable accounts are significantly depleted relative to accounts with beneficiary designations, that could cause a major issue. There might not be enough to counterbalance the tax-deferred assets passed to a lower-rate child. Then the higher-rate child would be out of luck.

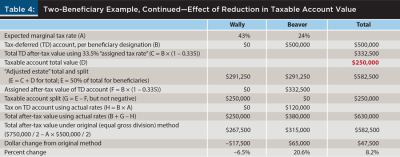

In the example above, suppose $250,000 is unexpectedly withdrawn from the taxable account before death. All other assumptions stay the same, including 100 percent of the tax-deferred account going to Beaver. An executor generally can’t change the beneficiary designation or make Beaver pay back money to Wally, so this plan fails the “do no harm” test. See Table 4, with the key assumption change shown in red.

One way to mitigate this risk is to build “cushion” into the calculation of the split in the beneficiary designation. In this example, allocating the tax-deferred account 87 percent to Beaver and 13 percent to Wally (instead of 100 percent and 0 percent) would enable an equitable split. Note that the cushion has a cost: Total after-tax value improvement decreases from $47,500 to $35,150. That’s because $65,000 of the tax-deferred account is taxed at a rate 19 percent higher.

In addition to building in cushion, there are other actions that can mitigate the risk of an inadequate taxable account balance.

- Consider the full financial plan, especially the retirement income strategy,4 when estimating future asset values.

- Perhaps even more regularly than with the tax rate risk, revisit the strategy often to update asset value estimates.

- Include language in the will that clearly explains what happens if there is a shortfall in taxable assets.

Testing the Framework for a Two-Beneficiary Scenario

The study evaluated the impact of this strategy for beneficiaries across many different combinations of beneficiary tax rates and asset mixes.

Beneficiary marginal tax rates evaluated were 12 percent, 24 percent, 28 percent, 38 percent, 43 percent, and 47 percent. Those are based on current federal rates from 12 percent to 37 percent, plus hypothetical state marginal tax rates ranging from 0 percent to 10 percent. While not exhaustive, this provides a set of reasonable possibilities. For two beneficiaries, there were 11 pairs of these rates with at least 10 points between them. As previously noted, a small gap reduces the value of the strategy and makes it likelier that someone will be adversely affected if the situation changes.

Three types of assets were considered. Two of them are passed by beneficiary designations: tax-deferred (such as 401(k)s and traditional IRAs) and tax-free (such as Roth or most life insurance death benefits). The third, a taxable account, is passed via a will or trust.5

The combinations of asset values assumed that tax-deferred accounts represented 30 percent to 70 percent of the total value at death (before taxes), tax-free accounts represented 0 percent to 50 percent, and taxable accounts represented 20 percent to 70 percent. Using increments of 10 percent, there were 20 asset mix combinations evaluated. Those ranges were informed by experimentation and by earlier observations: low proportions of tax-deferred or taxable assets would sharply limit the value or feasibility of the strategy.

The objective of the analysis is improvement in total after-tax value to nonspouse beneficiaries. In that calculation, tax-deferred accounts are taxed at each beneficiary’s marginal rate. Tax-free and taxable accounts pass tax-free. As noted earlier, taxable accounts are assumed to receive a full step-up in basis. One key assumption to note is that this is based on asset values at the parent’s death, so it does not consider subsequent returns or taxes on those returns. That assumption will be discussed further in the section “Additional Consideration: Asset Returns After the Parent’s Death.”

There are two types of decision variables. First are the percentages allocated to each beneficiary for tax-deferred and tax-free accounts. Since the percentages need to add to 100 percent for each account type, there are only two such variables in the two-beneficiary case. The second is the assigned tax rate, described above. In general, the allocation percentages drive the level of improvement, whereas the assigned tax rate drives the split of that improvement across beneficiaries.

The main constraint is that no beneficiary can be worse off under the strategy than if all assets were divided evenly based on before-tax values. The study also ensured that no allocations were negative and that the beneficiary designations did not cause an inadequate taxable account, such as shown in Table 4.

In addition to calculations assuming perfect knowledge of the future, the study considered sensitivity to changing tax rates and asset values. The “do no harm” constraint was imposed in each scenario for a range of beneficiary marginal tax rates five percentage points above or below expectations.6 Separately, sensitivity to asset value changes was evaluated by requiring a cushion so that taxable account values would be adequate even if the account decreased by 50 percent versus the original assumption. These sensitivity constraints are certainly not intended to represent the full range of possibilities. Financial planners should consider the facts for specific clients. Also note that the results displayed are still for the original assumptions; sensitivity analysis just added constraints.

Process to Determine the Decision Variable Values

For two beneficiaries, the process is relatively simple.

- Set the assigned tax rate. As noted earlier, this depends on how you want the improvement to be shared. In the study, two methods were evaluated: equal sharing of the improvement (assigned rate equal to midpoint of beneficiary rates) and highest possible rate while satisfying constraints and giving at least a trivial benefit to the higher-rate beneficiary.

- Allocate as much of the tax-deferred account to the lower-rate beneficiary as possible, subject to the taxable account constraint (with adequate cushion when sensitivity is tested).

- Allocate as much of the tax-free account to the higher-rate beneficiary as possible, also subject to the taxable account constraint (in this case, to prevent the higher-rate beneficiary from getting too much).7

Results for the Two-Beneficiary Framework

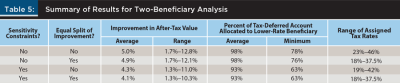

Across the 220 scenarios, employing the strategy improved after-tax value to beneficiaries by 1.3 percent to 12.8 percent, compared with dividing assets equally before taxes. The improvement depended on whether sensitivity constraints were enforced and, to a lesser extent, whether the assigned tax rate was set to evenly split improvement between the two beneficiaries. Table 5 summarizes those results along with a few helpful metrics.

There are a few interesting patterns in Table 5. First, you will notice that enforcing an equal split of the improvement doesn’t dampen the overall benefit much. Second, there is still a wide range of improvements in each row—those are largely explained by the beneficiary tax rates and, to some extent, by the account mix.

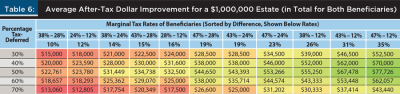

Table 6 provides further detail on the benefits for different combinations of assumptions. It reflects the settings in the bottom row of Table 5: using sensitivity constraints and requiring an equal split of after-tax improvement.

It is not surprising that results generally improve as the tax rate gap widens (moving to the right). It is less intuitive that results would start to tail off after tax-deferred assets increase to beyond 50 percent of the portfolio. More tax-deferred assets would appear to mean more opportunity for shifting to a lower rate. Recall, however, that if there’s not enough money in other accounts to compensate, the percentage of the tax-deferred account left to the lower-rate child needs to be reduced.8

The numbers in Table 6 are directly scalable for different estate values (assuming the marginal tax rates are still accurate). For example, someone leaving a $3 million estate (50 percent in tax-deferred accounts) to beneficiaries whose tax rates are 23 percentage points apart could improve after-tax legacy by nearly $160,000. Planners and their clients need to evaluate whether the benefit is worth the effort and risks, but the potential improvement can be meaningful.

Extending the Two-Beneficiary Framework

As the number of beneficiaries increases, the strategy gets harder to implement. The benefits can also be significantly smaller than for comparable two-beneficiary cases. One key observation is that a planner really needs to “look out for Jan Brady.”9 In other words, if you’re not careful, a child in the middle (in terms of tax rate) could get shortchanged.

The study analyzed results for three-beneficiary cases. It used the same tax rate combinations as the two-beneficiary analysis, adding a child with a rate in the middle (or equal to one sibling). Asset mixes, the objective function, variables, constraints, and sensitivity checks all remained the same.

To determine the decision variables, a method similar to the two-beneficiary analysis was used. Essentially, it treats the middle child like either the high- or low-rate child (whichever has the closer rate). The assigned tax rate is the midpoint between the middle rate and either the high or the low rate (whichever is further).

That method did successfully satisfy all constraints, including the sensitivity checks. On average, improvement over the even distribution approach was 3.6 percent of after-tax value. That compares with 4.1 percent for the two-beneficiary cases. However, for specific scenarios, total improvement for three-beneficiary families could be sharply lower—as much as 41 percent less than for comparable two-beneficiary families.

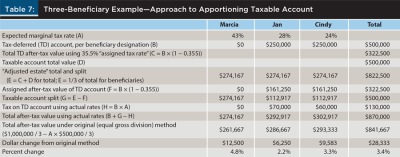

Table 7 shows one example—the same as for Wally and Beaver earlier but now with a middle child at a 28 percent rate. That makes the “assigned tax rate” 35.5 percent, which is the midpoint of 28 percent and 43 percent.

Adding a middle child reduces the total improvement from $35,150 in the two-beneficiary case (with “cushion”) to $28,333. Also note that under this method, the three beneficiaries do not share the improvement equally. In many cases, the improvement is split 50–25–25, with the middle child never getting 50 percent. While this might seem disappointing for Jan, remember that she still gets more than if the strategy were not employed.

It is often possible to get close to an even split of the improvement, primarily by tweaking the assigned tax rate (away from the rates of the children who are treated the same in the method described).10 Making these adjustments increased the average percentage of improvement that went to the middle child from 23 percent to 29 percent. But there are also cases where there is not really much room to adjust. The total improvement generally did not decrease significantly (8 percent at most) due to these adjustments.

The study did not analyze cases with four or more beneficiaries, but it seems that strategies could be developed. However, the potential benefit would tend to decrease further, and the likelihood of harmful tax rate changes increases. It becomes harder to choose an assigned tax rate that doesn’t harm someone, even if actual beneficiary tax rates only change modestly.

Additional Consideration: Asset Returns After the Parent’s Death

As previously noted, the calculations in this study are based on asset values at the time of death. This may prompt another question: Should we consider the different values of account types after death (in terms of taxes on subsequent returns)?

This strategy (and implementation method) properly accounts for the allocation of tax-deferred versus Roth accounts, even considering taxes on subsequent returns. That is consistent with prior research showing that someone whose tax rates stay constant over time will get the same results from comparable Roth or tax-deferred contributions (Crain and Austin 1997).

However, this method values Roth accounts and taxable accounts the same, which is not accurate regarding returns after inheritance. Returns for the Roth account are assumed to be tax-free, whereas taxable account returns are generally taxed. The additional value of those tax-free gains depends on several factors, including expected returns, tax rates, and tax treatment of the returns in a taxable account (e.g., long-term capital gains versus ordinary income). DiLellio and Ostrov (2020) analyzed this valuation in the context of tax-efficient withdrawal strategies.

A separate analysis to the main study estimated the benefit to Roth assets after inheritance compared with taxable assets using a variety of assumptions. In all cases, the time horizon was 10 years, based on the SECURE Act distribution requirement for most retirement accounts.

For example, an efficiently managed taxable account generating a 7 percent return and taxed at the 20 percent capital gains rate at the end of 10 years would be worth 5 percent less than a comparable inherited Roth account.11 Under many reasonable assumptions (with continued investment), that difference would be roughly 4 percent to 8 percent. Those numbers are similar to ones estimated by DiLellio and Ostrov.

So, what do we do with that information? It would be possible to write a will to account for an estimated taxable account “penalty.” However, this penalty would likely be difficult to explain to an estate attorney, let alone family members and the executor.

Therefore, the study’s separate analysis evaluated whether this factor might outweigh the strategy’s after-tax improvement for any beneficiary. Thankfully, using a 5 percent penalty assumption, this did not outweigh the benefits in any two-beneficiary scenarios evaluated. The “do no harm” mandate was not violated.

Note that in roughly three-quarters of the scenarios evaluated, the higher-rate child inherits more of the taxable account and bears this penalty. You might take the stance that the higher-rate child can handle it. That child may also be in a better position to hold a taxable investment indefinitely, so it ultimately gets the step-up in basis again! In cases where the lower-rate child inherits more taxable assets (typically when Roth assets going to the higher-rate child are significant), you could consider increasing the assigned tax rate modestly to shift some benefit in that direction.

Overall, this aspect seems less important than others, and it depends largely on what the beneficiaries do after receiving the inheritance. As such, it could be reasonably ignored by a planner—but it’s helpful to be armed with this information in case questions arise.

Additional Considerations: Estate Planning Factors

Estate planning is complex, and this paper does not address all of the factors that should be considered. However, three specific factors are worth mentioning.

First, remember that large inheritances can significantly change the beneficiaries’ tax rates (Young 2020). That is particularly important after the passage of the SECURE Act, with its 10-year distribution requirement for most nonspouse beneficiaries. Even before that act, a beneficiary could choose to take large distributions quickly, despite the adverse tax impact. This factor should be considered when deciding whether to implement a beneficiary designation strategy, and if so, in determining the assigned tax rate.

Second, there are other strategies that could address the tax burden on tax-deferred accounts. One common approach is to donate some or all of those tax-deferred assets to charity, which would not be taxed. Another technique is for a high-rate beneficiary to disclaim certain assets. Keep in mind, however, that disclaiming is also a complex strategy, and you need to be careful to ensure that the disclaimed assets will pass in a favorable manner. In some cases, it may add flexibility to name a trust as a contingent beneficiary (including for purposes of disclaimed assets), but that approach also requires careful planning. Choate (2018) provides detailed information on these techniques, albeit prior to the SECURE Act. And, of course, Roth conversions from tax-deferred accounts to tax-free accounts can reduce or eliminate the income tax issue for beneficiaries.

Third, remember that the best laid plans can be inadvertently derailed by well-meaning advisers in the future. One example is that advisers often recommend “transfer on death” (TOD) designations to avoid probate and simplify transfer of assets. Adding a TOD designation to an account that is required to balance out the adjusted estate could have very negative unintended consequences.

Implications for Financial Planners

For a client with beneficiaries in significantly different tax brackets, this strategy can generate meaningful tax savings. This paper shows how it can be implemented by a planner and estate attorney, using an “assigned tax rate” in the will that is between the beneficiaries’ expected marginal tax rates. The allocation percentages specified in beneficiary designations can direct more of the tax deferred assets to those with lower tax rates. By choosing those numbers carefully, a planner can split the benefit of the strategy among beneficiaries and reduce the risk that any beneficiary will be worse off as a result of this approach.

However, this strategy does have risks and is probably inappropriate for many clients. The alternative is easy and probably uncontroversial to implement—simply allocate all accounts equally using gross (before-tax) values.

You may consider using this checklist of factors to evaluate whether the strategy is worth pursuing:

- Large tax rate gap between beneficiaries

- Relatively balanced asset mix (tax-deferred versus other assets)

- Somewhat stable beneficiary tax rates and established retirement income plan

- Family willing to discuss finances, including views on fairness

- Parent who has demonstrated ability to execute plans and make necessary adjustments

- Estate attorney who buys into the strategy (and will quickly execute codicils to change the assigned tax rate if needed)

- Strategy not in conflict with other planning techniques being employed

The financial planner must also stay on top of changes and be willing to forgo the strategy if the benefits don’t seem commensurate with the risks and effort. It needs to be well documented, so the client and any professionals involved in the future understand the strategy.

Finally, remember that the value of family harmony should not be underestimated! If this or any complex strategy threatens to cause ill will, that’s a risk you should probably avoid.

Citation

Young, Roger. 2023. “Increasing After-Tax Legacy for the Next Generation by Coordinating Beneficiary Designations and Estate Plans.” Journal of Financial Planning 36 (6): 78–92.

Endnotes

- Note that the SECURE 2.0 Act, passed in late 2022, does not significantly affect strategies discussed in this paper. It may result in more investors having a mix of retirement account types, due to rules enabling or requiring Roth contributions in some situations.

- Two attorneys, Jeffrey Renner and Cristin Lambros, provided valuable insights on this topic, including descriptions of how estate documents can implement strategies with non-probate assets. Both, as well as attorney Jeffrey Condon, shared important considerations around charitable strategies, family dynamics, and real-world estate planning challenges. Note that their assistance should not be interpreted as an endorsement of the specific strategies in this paper.

- Because state tax rates differ, someone could potentially face a lower marginal tax rate than someone with lower income. Therefore, this study generally refers to “lower-rate” beneficiaries rather than “lower-income.”

- Many researchers have identified tax-efficient withdrawal strategies that would draw down accounts unevenly. For one example, see www.troweprice.com/Withdrawalstrategiesreport.

- For purposes of this strategy, a health savings account should be considered tax-deferred, because a nonspouse beneficiary pays ordinary income tax on the inherited value. Life insurance death benefits are usually tax-free and are distributed based on beneficiary designations, like a Roth IRA; however, regarding tax treatment after inheritance, they are more like a taxable account. This is relevant to the subsequent section “Additional Consideration: Asset Returns After the Parent’s Death.”

- This test used the initial assumptions to determine the decision variables (assigned tax rate and beneficiary designation percentages). Then it calculated the after-tax value for each beneficiary under the revised tax rate assumption (plus or minus five points). This value was compared with the method of assigning all accounts equally before taxes. Importantly, the revised tax rates are used for both calculations of value. Also note that only the change in a child’s own tax rate affects his or her valuation—a change to a sibling’s rate has no impact.

- Note that the second and third steps depend on the first one. A higher assigned tax rate reduces the valuation of the tax-deferred account for purposes of dividing the taxable account. Therefore, it affects how much tax-deferred can be safely allocated to the lower-rate beneficiary (and possibly how much tax-free can be allocated to a higher-rate beneficiary). For that reason, increasing the assigned rate can modestly increase the total improvement—but in a very unequal fashion. That effect also explains why small increases in the marginal tax rate gap in Table 6 do not always increase the improvement.

- The table shows averages for given tax-deferred percentages. Note that the split between tax-free and taxable assets does have some impact under the study’s assumptions, with higher tax-free assets sometimes increasing the improvement. For example, the table shows an average improvement of $43,393 for the scenario used early in the paper (50 percent tax-deferred, with beneficiary tax rates of 43 percent and 24 percent). That is higher than the $35,150 benefit noted after Table 4 (with adequate cushion), due to inclusion of cases with tax-free assets. Because this impact is affected by the cushion constraint calculation (on taxable accounts only), it should not be considered a primary conclusion of the study.

- Examples are for illustrative purposes only. Obviously, birth order does not dictate earning ranking. In fact, as a middle child, the author likes to imagine that the fictional Jan Brady out-earned older sister Marcia as an adult.

- This was analyzed using Excel’s Solver feature, with the objective of maximizing the smallest dollar improvement among the three children. The initial starting points, which affect how well Solver works, were the solutions determined as described earlier. Note that Solver does not necessarily generate a global optimal solution, but in this analysis the solutions (after a small number of minor manual adjustments) appeared very reasonable.

- This does reflect annual distributions from the Roth account, reinvested in the taxable account. The comparison at the end of 10 years is the remaining taxable account balances.

References

Choate, Natalie B. 2018. Life and Death Planning for Retirement Benefits. 8th ed. Boston: Ataxplan Publications.

Crain, Terry L., and Jeffrey R. Austin. 1997. “An Analysis of the Tradeoff Between Tax Deferred Earnings in IRAs and Preferential Capital Gains.” Financial Services Review 6 (4): 227–242.

DiLellio, James, and Daniel Ostrov. 2020. “Toward Constructing Tax Efficient Withdrawal Strategies for Retirees with Traditional 401(k)/IRAs, Roth 401(k)/IRAs, and Taxable Accounts.” Financial Services Review 28 (2): 67–95.

Potts, Tom L., and William Reichenstein. 2015. “Which Assets to Leave to Heirs and Related Issues.” Journal of Personal Finance 14 (1): 9–16.

Vnak, Brian. 2019. “Equal Shares for Heirs? Not Unless You Take Taxes into Account.” Kiplinger. www.kiplinger.com/article/retirement/t021-c032-s014-equal-shares-for-heirs-take-taxes-

into-account.html.

Young, Roger. 2020. “The Roth/Pretax Decision in Late Career Years: The Increasing Importance of Accumulated Assets in Light of the SECURE Act.” Journal of Financial Planning 33 (12): 59–68.

Disclosure: The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of T. Rowe Price. Information and opinions are derived from proprietary and nonproprietary sources deemed to be reliable; the accuracy of those sources is not guaranteed. This material is provided for general and educational purposes only and is not intended to provide legal, tax, or investment advice. This material does not provide recommendations concerning investments, investment strategies, or account types; it is not individualized to the needs of any specific investor and is not intended to suggest that any particular investment action is appropriate for you, nor is it intended to serve as the primary basis for investment decision-making. Any tax-related discussion contained in this material, including any attachments/links, is not intended or written to be used, and cannot be used, for the purpose of (1) avoiding any tax penalties or (2) promoting, marketing, or recommending to any other party any transaction or matter addressed herein. Please consult your independent legal counsel and/or professional tax adviser regarding any legal or tax issues raised in this material.