Journal of Financial Planning: February 2024

Executive Summary

- The U.S. population is aging. One in six people in the United States are 65 years old or older (Caplan 2023). Approximately 70 percent of this age group is expected to need some form of long-term care at some point (Digital Communications Division 2022). Because of the projected growing need for long-term care, understanding how people are thinking about and planning for their potential long-term care needs is vital.

- Drawing on data from a series of semi-structured focus groups (N = 84) and a national survey (N = 1,450), this study sought to understand people’s perceptions, interests, language, and emotions related to long-term care and long-term care planning.

- Results suggest that most people have not seriously considered that a long-term care event might happen to them, and they were mixed about whether they were financially prepared to afford their care should they experience a long-term care event. About one-third of survey respondents said that they had not spoken to anyone about the possibility of experiencing a long-term care event. Women, people with children, and people with current or former caregiving experience generally expressed greater interest in long-term care insurance offerings.

- Implications of this research highlight opportunities for financial professionals to provide education and dispel misconceptions about long-term care, to act as facilitators in conversations with loved ones around long-term care, and to tailor solutions for their clients’ needs.

Sophia Ashebir (email HERE) is a technical associate at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology AgeLab, where she is involved in research related to caregiving, vaccines and preventive health, and long-term care. She received her B.A. in economics and comparative race and ethnicity from Wellesley College.

Alexa Balmuth (email HERE) is a technical associate at the MIT AgeLab, where she contributes to research related to family caregiving and longevity planning. Alexa earned her B.S. from Tulane University where she studied psychology and public health.

Samantha Brady (email HERE) is a research specialist at the MIT AgeLab and a Ph.D. student in the sociology department at Brown University. Her work focuses broadly on employment, family, and implications of an aging U.S. population.

Lisa D’Ambrosio, Ph.D., (email HERE) is a research scientist at the MIT AgeLab. Her research includes decision-making around longevity preparedness; caregiving; well-being, social isolation, and loneliness; transportation and mobility; and technology use and adoption. Her Ph.D. is from the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and her A.B. is from Brown University.

Adam Felts (email HERE) is a researcher and writer at the MIT AgeLab. He conducts research on the experiences of family caregivers and the future of financial advice. He received his master of fine arts in creative writing from Boston University in 2014 and his master of theological studies from Boston University in 2019.

Joseph Coughlin, Ph.D., (email HERE) is founder and director of the MIT AgeLab, where his work explores how global demographics, technology, and changing behaviors are transforming business and society. He received his Ph.D. from Boston University.

JOIN THE DISCUSSION: Discuss this article with fellow FPA Members through FPA's Knowledge Circles.

FEEDBACK: If you have any questions or comments on this article, please contact the editor HERE.

NOTE: Click on the images below for PDF versions

With an aging population and a projection that adults 65 years and older will outnumber children by 2030 in the United States, long-term care and long-term care planning are increasingly relevant topics for many people as the demand for these services is forecast to grow (Gibson 2018; Jong, Zeidler, and Damm 2022; Guo, Konetzka, Magett, and Dale 2015). Seventy percent of people age 65 and older are expected to need some form of long-term care at some point (Digital Communications Division 2022), and as people grow older, they are at greater risk for chronic diseases and conditions, including dementia. In the CDC’s National Health Interview Study, 85.6 percent of adults ages 65 years and older had one or more chronic conditions, 56 percent reported two or more chronic conditions, and 23.1 percent of adults were managing three or more conditions (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2015).

Long-term care and long-term care services are expensive and are often not covered by health insurance providers or Medicare (Medicare n.d.; Pokorski 2021). AARP reported that paying out of pocket for these expenses could cost $140,000 on average (Stark 2018), although costs can vary depending on geographic location and extent and nature of the care needed. A 2023 Forbes article reported that the average annual cost for a private room in a nursing home can range between $108,000 and $180,000 (Wigand and Shega 2023). In-home services, aides, and paid caregivers are also costly. On average, the projected cost of a home health aide in the United States in 2024 costs roughly $27 per hour, but these costs can vary greatly depending on geographic location; for example, in Minnesota, the projected average cost is over $35 per hour (MassMutual n.d.).

To prepare for and hedge against future care expenses, some people choose to purchase an insurance policy with long-term care benefits. A 2023 Boston Globe article, however, reported that less than 10 percent of older adults have a long-term care insurance policy (Weisman 2023), and in general the consensus is that the purchase of private long-term care insurance falls below the projected need for it (Lambregts and Schut 2020).

The decision to invest in a long-term care policy involves many considerations, including its cost, the perspectives of loved ones (Patterson 2022), the potential availability of other family members to provide care, the involvement of financial professionals, and clarity on policy benefits (Miller et al. 2022). People’s individual characteristics also affect their likelihood of having a long-term care insurance policy. For example, awareness of being at risk for a long-term care event was associated with a greater likelihood of having purchased such a policy (Lambregts and Schut 2020), as was scoring higher on the personality trait of conscientiousness (Cherry and Asebedo 2022) or having greater numeric abilities or financial literacy (McGarry et al. 2016; Lambregts and Schut 2020). Research has also found that experience with caregiving leads people to be more likely to purchase or intend to purchase a long-term care insurance policy (Broyles et al. 2016; Yeh, Wang, Chou, and Chen 2021). Long-term care insurance is more likely to be held by individuals with higher levels of income (Allaire, Brown, and Wiener 2016; Lambregts and Schut 2020; Yeh, Wang, Chou, and Chen 2021) and to be typically purchased by people in later midlife; 55 percent of policy holders purchased a policy between the ages of 55 and 65 (American Association for Long-Term Care Insurance n.d.).

Past work also suggests that conversations with people about long-term care needs may also be related to people’s purchase of an insurance solution. Having a better understanding of long-term care insurance products or working with a financial professional were positively associated with long-term care insurance uptake (Lambregts and Schut 2020). Sperber et al. (2017) found that conversations between adult children and their parents emphasizing the ability to maintain autonomy were most successful in influencing parents to purchase a policy.

Drawing on the results of this previous work, the research conducted here focuses on a sample of likely customers for existing long-term care solutions, to provide insights into the assumptions that they may have about their long-term care needs. More specifically, the analysis examines people’s own assessments of their risk for experiencing a long-term care event and their interest in long-term care insurance solutions, as well as their assumptions, rightly or wrongly, about how they would finance and provide for their own long-term care needs and whether they have had conversations with others about these. The analysis examines the impacts of some of the key variables identified in other work. Additionally, it includes results to describe how people who identify as LGBTQIA+ think about long-term care and related services.

These results will be useful for informing financial professionals about what clients’ prior beliefs and assumptions might be about their own future care needs and paying for future care, which in turn will be useful in planning for more constructive conversations about long-term care with clients and tailoring solutions to their needs.

Methods

To better understand perceptions, interests, language, and emotions related to long-term care and long-term care planning, as well as tools and products related to long-term care, MIT AgeLab conducted a series of focus groups and a national online survey. The results found here are led by the research from the national survey.

In November and December 2022, MIT AgeLab surveyed 1,450 individuals who did not at the time possess an insurance policy that had long-term care benefits. Survey participants were between the ages of 40 and 64 and varied by marital status, family composition, caregiving experience, and financial management practices. Respondents all had household savings of more than $50,000 and retirement account savings of more than $300,000.

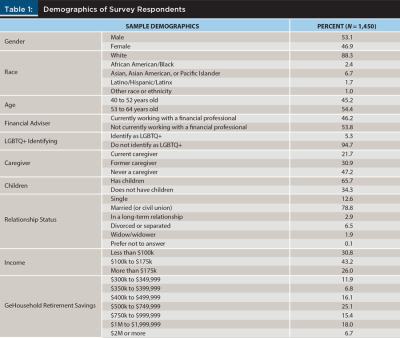

Respondents completed a 60-item survey with questions regarding conversations they had about long-term care, their wishes regarding who they would like to receive care from, how respondents hoped to finance a potential long-term care event, and more. Sample demographics are described in Table 1.

Results

Perceptions of Risk Related to Long-Term Care Events

Results from the survey suggest that most people have not given much thought to the possibility of experiencing a long-term care event. When asked “about the possibility of you yourself experiencing a long-term care event at some point in your life,” 44.6 percent of respondents reported they had thought “some” about it, and 24.6 percent said they had thought a “good” or “great” deal about it. Over half of respondents indicated that they thought they were at moderate risk for a long-term care event, and about a third thought they were at low or no risk (people who reach age 65 have an estimated 70 percent chance of experiencing a long-term care event).

Similarly to their perception of their risk of experiencing an event, most respondents did not highly rate their financial risk related to a long-term care event. Only 22.2 percent said they thought they were “very” or “extremely” financially at risk from such an event, compared to the 37.1 percent who said they were only “slightly” or “not at all” at risk financially.

Interest in Long-Term Care Insurance Policies

A substantial number of people placed high importance on having an insurance policy that provided long-term care benefits, with 41.1 percent of people saying that having such a policy was “very” or “extremely” important to them versus the 24.9 percent who said it was only “slightly” or “not at all” important.

Among partnered respondents, 69.7 percent rated the importance of their spouse having a policy the same as they rated it for themselves, but 24.1 percent placed greater importance on their spouse having such a policy than they did for themselves.

Additionally, over three-quarters of the sample indicated some degree of interest in learning more about an insurance policy that provided long-term care benefits.

Respondents were less likely to believe, however, that they would actually purchase a long-term care policy. Only 45.3 percent of the sample indicated some degree of likelihood of purchasing such a policy for themselves within the next two years; 46.2 percent indicated some degree of likelihood of purchasing a policy for their spouse.

Financing Long-Term Care

Respondents were asked about their perceived level of financial preparedness if a long-term care event were to occur and what plans they had in place to finance such an event. First, respondents were asked to what extent they agreed or disagreed with the statement, “I feel financially prepared if I were to experience a long-term care event.” Response options were on a five-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” Responses were distributed in an approximate bell shape, with the plurality of respondents (35.6 percent) indicating that they slightly agree, following by “agree” (23.9 percent), “slightly disagree” (19.4 percent), “disagree” (11.3 percent), “strongly agree” (6.1 percent), and “strongly disagree” (3.7 percent). The distribution of results suggests a slight skew toward feeling financially prepared for a long-term care event. However, very few respondents selected “strongly disagree” or “strongly agree,” instead opting for weaker responses. These less definitive responses may indicate that individuals do not have a concrete idea of what financial preparedness means relative to managing a future long-term care event.

Respondents were asked how they would pay for a long-term care event: “If you were to have a long-term care event in the next year and did not have an insurance policy that provides long-term care benefits, which of the following resources would you expect to use to cover the costs of your care?” Over two-thirds (68.1 percent) of respondents said they would use personal savings (outside of any retirement savings) to finance their care. About half of the sample also indicated investments (57 percent), private health insurance (51.4 percent), and dedicated retirement savings (49 percent). Fewer respondents selected Medicare, Medicaid, or government health insurance (31.2 percent), or home equity or monies realized from a home sale (20.8 percent). Less than one in 10 (8.1 percent) indicated that they would receive financial help from their family. Finally, 4.7 percent indicated that they didn’t know how the costs of a potential long-term care event would be covered.

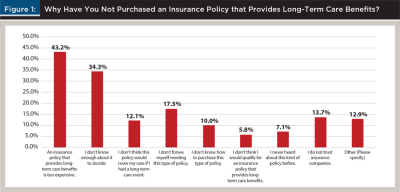

While respondents in this sample indicated at least a moderate level of confidence in their ability to finance a long-term care event, cost was still a highly important factor in the long-term care planning process. Focus groups conducted prior to the survey surfaced three primary concerns for participants about long-term care: care choice, family, and cost. In the survey, we asked respondents to indicate the level of importance of these three factors, and survey participants placed significantly more importance on cost than the other two factors. Additionally, when respondents were asked, “Why have you not purchased an insurance policy that provides long-term care benefits?” the plurality (43.2 percent) selected “an insurance policy that provides long-term care benefits is too expensive.” The second most frequent response was “I don’t know enough about it to decide” (34.3 percent), while other response options were selected by less than 20 percent of respondents (see Figure 1). Overall, while individuals in this sample may have a high level of comfort that they have the financial resources to pay for long-term care expenses, cost is still the most salient factor when making long-term care plans, and it remains a main barrier to purchasing an insurance policy that provides long-term care benefits.

Expected Care Providers

While finances are a significant part of long-term care planning, considering the logistics of care is also important. Survey respondents were asked, “In the event you were to need a care provider, who do you think your care provider would be?” Respondents provided a wide range of responses, with spouse or partner being the most prevalent option for those with partners (56.6 percent). Children were also commonly seen as potential care providers, with 26.8 percent of respondents choosing this option. Siblings (7.2 percent), other family members (7.2 percent), and friends (3.3 percent) were less commonly chosen. Outside of family, over one-third of respondents stated that a paid professional would likely be part of their care team (39.1 percent), while only a handful of respondents indicated that some form of technology would help provide care (3.3 percent). Finally, 11.6 percent of respondents did not know who might serve as a care provider for them.

It is important to note, however, that indicating that someone would be part of their care team did not necessarily mean that they had communicated their care expectations to that person.

Conversations

A third of respondents (35.6 percent) said they had not spoken to anyone about the possibility of experiencing a long-term care event. Among individuals who did report speaking to someone, conversations most often took place among family and friends rather than with professionals. Forty-eight percent of respondents had spoken with a spouse or partner, followed by 15 percent with friends, 13.9 percent with a financial professional, and 12.3 percent with children. Fewer than 10 percent of the sample reported speaking with siblings, parents, grandparents, other family members, coworkers, medical professionals, an insurance agent or broker, or someone else.

These findings suggest a marked gap in conversations with professionals about the possibility of experiencing a long-term care event. While discussing future care needs with a spouse or partner is important, professionals may be better situated to provide knowledge, insights, or resources.

The survey further questioned respondents about whether they had discussed with loved ones their hopes and expectations for receiving care. For each family member they thought might provide care for them, respondents were asked, “Have you spoken to the following about your hope or expectation that they would provide care for you should you need it?” A majority (67.8 percent) of those who had discussed the possibility of needing long-term care with a spouse or partner had also discussed their future care hopes or expectations with them. Fewer had spoken with siblings (47.5 percent), a friend (42.3 percent), children (41.3 percent), or other family members (30.4 percent) about this particular topic.

Demographic Factors

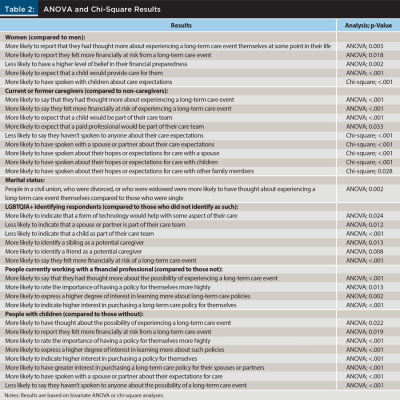

We ran one-way ANOVAs and chi-square tests to explore how different demographic factors might influence attitudes and behaviors related to long-term care planning.

In particular, being a woman, having caregiving experience, working with a financial professional, and having children all increased people’s activity and level of awareness across multiple dimensions related to long-term care. Findings below are based on one-way ANOVAs unless otherwise noted; findings based on chi-square tests are noted explicitly.

Gender. Woman were more likely to be engaged on the topic of long-term care than were men.

Women were more likely than men to report that they had thought more about experiencing a long-term care event themselves at some point in their life (F(1, 1,448) = [8.80], p = .003). Women were also more likely than men to report they felt more financially at risk from a long-term care event (F(1, 1,448) = [5.66], p = .018). Men displayed a higher level of belief in their financial preparedness than women (F(1, 1,448) = [9.32], p = .002).

Women were more likely than men to expect that a child would provide care for them (F(1, 1,448) = [24.59], p <.001).

Based on chi-square tests, women were more likely to have spoken with children about care expectations than were men (15.2 percent compared to 9.1 percent, X2 (1, N = 1,450) = 12.33, p <.001).

Caregiving status. Experiencing caregiving activates people’s awareness of long-term care as a concern.

People who were current or former caregivers (compared with those with no caregiving experience) were more likely to say that they had thought more about experiencing a long-term care event (F(1, 1,448) = [111.27], p <.001). They also were more likely to say they felt more financially at risk of such an event (F(1, 1,444) = [37.28], p <.001).

Those who were current or former caregivers were more likely to rate the importance of having a policy for themselves more highly (F(1, 1,444) = [35.38], p <.001). They were also more likely to rate the importance of having a policy for their partners more highly (F(1, 1,138) = [42.31], p <.001).

People who had current or former experience as a caregiver were more likely to express a higher degree of interest in learning more about such policies (F(1, 1,444) = [47.98], p <.001). They also showed a higher likelihood of interest in purchasing a policy for themselves (F(1, 1,144) = [53.73], p <.001).

Respondents with adult caregiving experience were more likely to expect that a child (F(1, 1,444) = [16.48], p <.001) and a paid professional (F(1, 1,444) = [4.54], p = .033) would be part of their care team. According to chi-square tests, caregivers were also less likely to say they haven’t spoken to anyone about their care expectations (25.7 percent compared to 46.3 percent). Caregivers were more likely to have spoken with a spouse or partner than non-caregivers (54.6 percent compared to 40.9 percent, X2 (1, N = 1,446) = 26.93, p = <.001).

Caregivers were significantly more likely than non-caregivers to have spoken about their hopes or expectations for care with a spouse (73.5 percent compared to 56.3 percent, X2 (1, N = 821) = 29.61, p = <.001); children (48.1 percent compared to 26.7 percent, X2 (1, N = 389) = 18.49, p = <.001); and other family members (41.5 percent compared to 17.6 percent, X2 (1, N = 104) = 7.12, p = .028).

Marital status. People in a civil union, who were divorced, or who were widowed were more likely to have thought about experiencing a long-term care event themselves (F(2, 1,403) = [6.74], p =.001) compared to those who were single.

Those who were married or in a civil union (F(2, 1,403) = [6.18], p =.002) were more likely to indicate higher interest in purchasing a policy for themselves.

LGBTQIA+. People who identified as LGBTQIA+ (F(1, 1,448) = [5.29], p =.022) were more likely to say they felt more financially at risk of a long-term care event (F(1, 1,444) = [50.80], p <.001).

Individuals who identified as LGBTQIA+ were less likely to indicate that a spouse or partner (F(1, 1,448) = [6.29], p = .012) or a child would be part of their care team (F(1, 1,448) = [13.13], p <.001), and they were more likely to identify a sibling (F(1, 1,448) = [6.20], p = .013) or a friend (F(1, 1,448) = [7.15], p = .008) as a potential caregiver.

Additionally, LGBTQIA+ identifying respondents were more likely to indicate that a form of technology would help with some aspect of their care (F(1, 1,448) = [5.11], p = .024).

Financial professional. People who were currently working with a financial professional (F(1, 1,448) = [29.01], p <.001) were more likely to say that they had thought more about the possibility of experiencing a long-term care event.

People were more likely to rate the importance of having a policy for themselves more highly if they were working with a financial professional (F(1, 1,448) = [6.22], p = .013). On average, people who were working with a financial professional (F(1, 1,448) = [9.43], p = .002) were more likely to express a higher degree of interest in learning more about such policies.

People who were working with a financial professional (F(1, 1,148) = [16.90], p <.001) were more likely to indicate higher interest in purchasing a long-term care policy for themselves. Working with a financial professional was also associated with greater interest in purchasing a long-term care policy for a spouse or partner.

Children. Having children may make long-term care a more salient topic.

People with children (compared to those without children) were more likely to have thought about the possibility of experiencing a long-term care event compared with those who did not have children (F(1, 1,448) = [5.25], p = .022). People who had children were also more likely to report they felt more financially at risk from a long-term care event (F(1, 1,448) = [5.49], p = .019).

People who had children were more likely to rate the importance of having a policy for themselves more highly (F(1, 1,448) = [12.37], p <.001).

People who had children (F(1, 1,448) = [41.21], p <.001) were more likely to express a higher degree of interest in learning more about such policies.

People who had children (F(1, 1,148) = [45.55], p <.001) were more likely to indicate higher interest in purchasing a policy for themselves. Having children was also associated with greater interest in purchasing a long-term care policy for their spouse or partner (F(1, 1,141) = [10.79], p <.001).

People with children were less likely to say they haven’t spoken to anyone about the possibility of a long-term care event (30.7 percent compared to 45 percent, X2 (1, N = 1,450) = 29.20, p <.001).

Respondents with children (56 percent) were more likely to have spoken with a spouse or partner about their expectations for care (32.7 percent, X2 (1, N = 1,450) = 70.85, p < .001).

Discussion

Our survey findings suggest that many people have given little thought to long-term care, including how to pay for care and the risk of a long-term care event occurring in their lives. This suggests an opening for financial professionals to serve as guides and educators on the topic of planning for care.

Seventy percent of people over the age of 65 are expected to need some form of long-term care in the future, which suggests a significant risk for individuals who can expect to live to their 80s and beyond. Yet one-third of survey respondents—who were selected based on having sufficient income and savings to make purchasing long-term care insurance a realistic choice—reported that they were at minimal or no risk of experiencing a long-term care event, suggesting a chasm between perception and probability for a significant number of people.

In addition to underestimating their risk of experiencing a long-term care event, many people may not understand the mechanics of paying for long-term care. Many survey respondents selected private or government health insurance programs as their source of funding for long-term care. However, private health insurance plans and Medicare cover only a limited set of services related to long-term care, while more comprehensive programs, such as Medicaid, have strict income eligibility criteria and require the liquidation of most family assets (Digital Communications Division 2022). Additionally, the majority of survey respondents reported that they would use their personal savings to pay for their care, likely indicating that they do not have a dedicated source of funding to finance a potential long-term care event. These results suggest that many people have not engaged in information-seeking about paying for long-term care and may be in need of counsel about what options are available for them to pay for future care needs.

Another need for many people is facilitation to engage in conversations with their families about potential future care needs. Over half of respondents with a spouse or partner said that they expected their partner to be their caregiver if they needed one. Of those individuals, nearly a third had never discussed this hope or expectation with their spouse or partner. Less than half of married respondents in general said that they had spoken with their spouse or partner about the possibility of experiencing a long-term care event. Conversations related to care and finances can be difficult for families. Financial advisers can act not only as educators but as facilitators for families to discuss challenging financial topics like long-term care.

While a significant number of people do not perceive a high risk of needing long-term care, and many have not engaged with their families on the topic, most respondents (more than 75 percent) in our survey said that they were interested in learning more about long-term care insurance. Yet only about one in 10 respondents had spoken about long-term care with a financial professional.

Certain demographic factors and life situations may activate people toward consideration of long-term care needs. For example, women show greater awareness of the risks of a long-term care event and are more interested in learning about long-term care products. They are also more likely to have engaged in conversations with people about long-term care. Similar patterns appear with current and former family caregivers, as well as with people who have children. The proximity of these groups (which themselves are often overlapping) to care responsibilities may make them more receptive toward conversations about planning for care. They also may be more conversant and understanding about topics related to the need for long-term care. Conversely, people who do not fit these descriptions may be in greater need of information about long-term care, as the topic may be less salient in their minds.

Advisers should engage with their clients on the topic of long-term care, providing education on probable risk, financial options for paying for care, and the importance of having open discussions with family members about expectations and desires related to care. For clients who say they have a plan for a long-term care event, advisers should ask deeper questions: Who do they expect to provide care for them? Have they talked to that person about their expectations? Is their financial plan to pay for care needs a realistic one? By serving as an agenda-setter and expert on planning for future care needs, advisers can increase their value for clients and help people be better prepared for life in older age.

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology AgeLab wishes to thank MassMutual for supporting this research.

Citation

Ashebir, Sophia, Alexa Balmuth, Samantha Brady, Lisa D’Ambrosio, Adam Felts, and Joseph Coughlin. 2024. “‘I Haven’t Really Thought About It’: Consumer Attitudes Related to Long-Term Care.” Journal of Financial Planning 37 (2): 64–76.

Bibliography

Allaire, B. T., D. S. Brown, and J. M. Wiener. 2016. “Who Wants Long-Term Care Insurance? A Stated Preference Survey of Attitudes, Beliefs, and Characteristics.” INQUIRY: The Journal of Healthcare Organization, Provision, and Financing. https://doi.org/10.1177/0046958016663728.

Binette, Joanne. 2021. “2021 Home and Community Preference Survey: A National Survey of Adults Age 18-Plus.” Washington, D.C.: AARP Research. https://doi.org/10.26419/res.00479.001. [Informed research.]

Broyles, Ila H., Nina R. Sperber, Corrine I. Voils, R. Tamara Konetzka, Norma B. Coe, and Courtney Harold Van Houtven. 2016. “Understanding the Context for Long-Term Care Planning.” Medical Care Research and Review: MCRR 73 (3): 349–68. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077558715614480.

Caplan, Zoe. 2023. “U.S. Older Population Grew From 2010 to 2020 at Fastest Rate Since 1880 to 1890.” United States Census Bureau. www.census.gov/library/stories/2023/05/2020-census-united-states-older-population-grew.html.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: National Center for Health Statistics. 2015. “Percent of U.S. Adults 55 and Over with Chronic Conditions.” www.cdc.gov/nchs/health_policy/adult_chronic_conditions.htm.

Cherry, Preston D., and Sarah Asebedo. 2022. “Personality Traits and Long-Term Care Financial Risks among Older Americans.” Personality and Individual Differences 192 (111560). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2022.111560.

Digital Communications Division (DCD). 2022. “Caregiver Resources & Long-Term Care.” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. www.hhs.gov/aging/long-term-care/index.html.

Gibson, William E. 2018. “Age 65+ Adults Are Projected to Outnumber Children by 2030.” AARP. www.aarp.org/home-family/friends-family/info-2018/census-baby-boomers-fd.html.

Guo, Jing, R. Tamara Konetzka, Elizabeth Magett, and William Dale. 2015. “Quantifying Long-Term Care Preferences.” Medical Decision Making: An International Journal of the Society for Medical Decision Making 35 (1): 106–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272989X14551641.

Jong, Lea de, Jan Zeidler, and Kathrin Damm. 2022 “A Systematic Review to Identify the Use of Stated Preference Research in the Field of Older Adult Care.” European Journal of Ageing 19 (4): 1005–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-022-00738-7.

Lambregts, Timo R., and Frederik T. Schut. 2020. “Displaced, Disliked and Misunderstood: A Systematic Review of the Reasons for Low Uptake of Long-Term Care Insurance and Life Annuities.” Journal of the Economics of Ageing 17 (100236). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeoa.2020.100236.

American Association for Long-Term Care Insurance. n.d. “Long-Term Care Insurance Statistics Data Facts 2020.” Accessed June 29, 2023. www.aaltci.org/long-term-care-insurance/learning-center/ltcfacts-2020.php.

MassMutual. n.d. “MassMutual: Compare Long-term Care Costs from State to State.” Accessed June 29, 2023. https://massmutualltccosts.hvsfinancial.com/.

McGarry, Brian E., Helena Temkin-Greener, Benjamin P. Chapman, David C. Grabowski, and Yue Li. 2016. “The Impact of Consumer Numeracy on the Purchase of Long-Term Care Insurance.” Health Services Research 51 (4): 1612–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12439. [Informed research.]

Medicare. n.d. “Long-term Care Coverage.” Accessed June 29, 2023. www.medicare.gov/coverage/long-term-care.

Miller, Julie, Samantha Brady, Sophia Ashebir, Lisa D’Ambrosio, Caryl Falvey, Matthew DiGangi, and Joseph F. Coughlin. 2022. “Connecting with Your next Generation Retiree Clients about Long-Term Care Planning.” Rethinking65. https://rethinking65.com/2022/11/08/connecting-with-your-next-generation-retiree-clients-about-long-term-care-planning/.

Patterson, Sarah E. 2022. “Educational Attainment Differences in Attitudes toward Provisions of IADL Care for Older Adults in the U.S.” Journal of Aging & Social Policy 34 (6): 903–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/08959420.2020.1722898. [Informed research.]

Pokorski, Robert. 2021. “Data-Based Approach to Engaging Clients in a Discussion of Long-Term Care.” Journal of Financial Planning 34 (07): 66–82. www.financialplanningassociation.org/article/journal/JUL21-data-based-approach-engaging-clients-discussion-long-term-care.

Santos-Eggimann, B. and Lionel Meylan. 2017. “Older Citizens’ Opinions on Long-Term Care Options: A Vignette Survey.” Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 18 (4): 326–335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2016.10.010. [Informed research.]

Sperber, Nina R., Corrine I. Voils, Norma B. Coe, R. Tamara Konetzka, Jillian Boles, and Courtney Harold Van Houtven. 2017. “How Can Adult Children Influence Parents’ Long-Term Care Insurance Purchase Decisions?” The Gerontologist 57 (2): 292–99. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnu082.

Stark, Ellen. 2018. “5 Things You Should Know About Long-Term Care Insurance.” AARP: Family Caregiving. www.aarp.org/caregiving/financial-legal/info-2018/long-term-care-insurance-fd.html.

Weisman, Robert. 2023. “As Population Ages, New Efforts to Boost Long-Term Care Insurance Are Surfacing.” The Boston Globe. www.bostonglobe.com/2023/04/10/metro/long-term-care-insurance-bill-massachusetts/.

Wigand, Molly, and Joseph Shega. 2023. “How Much Do Nursing Homes Cost?” Forbes. www.forbes.com/health/healthy-aging/how-much-do-nursing-homes-cost/.

Yeh, Shu-Chuan Jennifer, Wen Chun Wang, Hsueh-Chih Chou, and Shih-Hua Sarah Chen. 2021. “Private Long-Term Care Insurance Decision: The Role of Income, Risk Propensity, Personality, and Life Experience.” Healthcare (Basel, Switzerland) 9 (1): 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9010102.

Read More: “Data-Based Approach to Engaging Clients in a Discussion of Long-Term Care,” July 2021