Journal of Financial Planning: September 2017

The genesis of this article has been long in the making. Having begun my career in the financial services industry back in 1985 in really the only role available to women (as a sales assistant at a well-known brokerage firm), I have always had a deep respect for the critical importance of client service in working with our clients. In addition, I am fascinated by people and how they are built. I am always looking for ways to help people understand their strengths and talents and then maximize the use of those strengths in life and work.

And after several years of a close partnership with Virginia Tech’s financial planning program (including speaking, recruiting, and group Kolbe® assessment interpretation), it has become clear that we need to highlight and promote the value of non-client facing careers in the financial planning profession. Not everyone is built for, or motivated by, the pace and demands of client-facing work. Yet, they may be motivated to be of service and help people or to bring their analytical skills to bear as part of the overall financial planning process.

Elevating the Importance of Operations

Our profession has evolved. Outside of brokerages and wirehouses, sales assistants don’t really exist anymore. In most cases, they have been elevated to client service and operations titles and roles. In many financial planning firms, this role is seen as the lowest on the career ladder and often an entry-level position that can become a revolving door of associates who come and go.

What’s not surprising to us is that many people who intend to become financial planners are not necessarily good at the operations/client service role. The reasons why are predictable when you start to look at the skills and strengths needed to do the job well and how those might compare to that of a financial planner—especially those that are required to bring in new clients.

The goal of this article is to make the case for elevating the importance of operations/client service positions within planning firms and for creating stand-alone career paths that can lead to management and ownership opportunities in the future.

The importance of a skilled, competent professional in the operations/client service role cannot be underestimated. They are often the first person “talking” to the client. They generally handle trading, money distribution, and changes to accounts that can all create significant liability for a firm and the associated planner if not done well. These days, third-party distributions have become a critical point of responsibility and liability, and yet firms continue to put just-out-of-college employees in these roles.

Understanding the importance of having the right person (skills, training, and expertise) in this role is critical. In order for a firm to increase retention and continuity, it must be willing to create a professional and challenging career path that will attract the right caliber of employee, and provide appropriate training, skill development, and mentoring to support the operations associate in being successful.

The Right Fit for Operations

To understand what the “right” profile is for this role, we can use the Kolbe® assessment, as well as other assessments, to examine the strengths and characteristics needed to be successful in an operations/client service role.

First a word on assessments: they are not all alike. Assessments such as DiSC®, Myers-Briggs, and StrengthsFinder look at the affective (personality) traits in a person. They are important to understanding the personality of a candidate or employee, and in determining whether there is a good values fit. Having an introverted person in a job that will require ongoing group work, presentations, and interactions may not be a good fit. An employee with a lot of strength in the relationship area of the StrengthsFinder assessment may be great in the multiple-meeting, client-facing planner role.

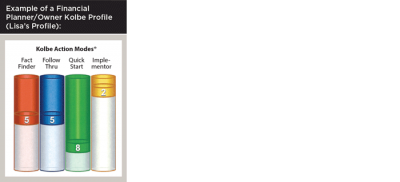

In the Kolbe® profile, there are four modes of “conative” (the act of doing; how someone will initiate action) strength or talent: Fact Finder, Follow Thru, Quick Start, and Implementor. Fact Finder looks at how you handle information. Follow Thru looks at how you handle systems and processes. Quick Start looks at how you handle risk and uncertainty. And Implementor looks at how you handle space and tangibles.

Kolbe® operates on a 1 to 10 scale in each mode, 1 to 3 being an area with a “contradicting” level of energy in this mode, 4 to 6 an area of “reacting” energy, and 10 being an area where the person “initiates” action from. So, a profile of 7542 would mean that someone initiates from the Fact Finder mode. You can initiate from up to three modes, but generally we see most profiles initiating from one to two modes.

Let’s look at two classic Kolbe® profiles to illustrate the difference in strengths needed to successfully fill a specific role within a planning firm:

Financial Planner/Owner

- People-facing;

- May be sales-oriented;

- May have to deal with the multi-faceted demands of running a business simultaneously with client-facing work;

- Often requires the ability to market oneself and the firm;

- The work and demands are often changing, requiring ongoing reprioritizing on the fly;

- And although it can be a role for someone detailed-oriented and process-oriented, it may often be interacting with clients who are not.

So, a potentially successful profile for that role might be like mine: 5582, an initiating Quick Start. My affective strengths include communication, empathy, and individualization.

Operations/Client Service

- Needs very good attention to detail;

- Needs to be good at completing work, following process, and perhaps creating workflows;

- Provides stability amidst the occasional chaos of a financial planning firm;

- Doesn’t have to be in client meetings all the time, can manage their time, work, and interaction with clients;

- And needs to be sensitive to compliance and legal issues that may be a liability for the firm.

So, a potential Kolbe® profile here might look like Andrew’s (author of the sidebar at the end of this article): 8831, an initiating Fact Finder and Follow Thru. Andrew’s affective strengths include responsibility, discipline, and analytical.

While there are some similarities, the differences are important. In the operations/client service role you want to see “initiating” Fact Finder and Follow Thru energy. You need an associate who is detail-oriented and good at getting things completed. In the planner role, the ability to deal with the risk of closing business (or not), of changing client meeting schedules, and the demands of business ownership require more flexibility and comfort with risk and uncertainty.

Simply put, the skill set needed for the client service role is important and different, and it may reflect the profile of a number of candidates coming out of undergraduate financial planning programs.

From our findings over the last four years and those of Caleb Brown’s work at New Planner Recruiting, a lot of students have profiles that initiate from Fact Finder and Follow Thru, and many less from Quick Start. That doesn’t mean it’s impossible for these students to become business owners and client-facing planners. However, the path may be different than the traditional founder of a financial planning firm, and some students may find their calling in financial planning operations.

An Effective Business Strategy

Most of us are familiar with the succession crisis within our profession. Many planners want to retire, but they are finding that the next generation of planners/business owners may be a bit reluctant to take on business ownership by themselves.

The model that seems to be emerging more often is a team of associates who buy out the founder/owner. So then, the idea of having a career operations associate (think COO), and one or two planner/adviser associates form a team for ownership could be a highly effective business strategy—perhaps better than the original single founder/owner approach.

Without a career path for operations, most firms will face bringing in outside operations expertise that may not be a complete fit within the firm in terms of understanding the history and mission of the firm, or even a good values fit.

In short, taking an intentional approach to building an operations career path may not only create stronger operations execution for the firm, but it may also provide a much-needed different “voice” on future management teams that can lead to stronger and better-run firms in the future.

Without this career path, we also face the possibility of alienating talented young associates who are not interested in a client-facing career, but very much want to be part of the financial planning profession.

Lisa A.K. Kirchenbauer, CFP®, RLP®, CeFT®, has been president of Omega Wealth Management LLC in Arlington, Virginia for the last 18 years. She is also a certified Kolbe® consultant and author of “The 5 Essential Skills™ of an Exceptional Planner.” She is a member of the Strategic Coach community, and Omega implements the Entrepreneurial Operating System (ESO) to run its business.

Sidebar

Choosing the Analytical Role: A Young Professional’s Experience by Andrew Mehari

Coming from virginia tech’s financial planning program and having experienced a financial planning internship in the summer of 2014, I had the idea that client-facing and advising roles were basically all the profession had to offer. At that time, I had known I wanted to work and grow in the planning/wealth management profession, but I wasn’t completely convinced that a client-facing adviser role was right for me.

During my internship, I was exposed to the behind-the-scenes of some of the analytical and client servicing sides of planning, but I also attended various client meetings and went through the motions of being an associate planner or paraplanner operating under the wing of a senior adviser.

To be honest, the client-facing portion of the internship was my least favorite. Centering my schedule around client meetings proved to be difficult, the meeting preparation process was arduous, and the almost daily face-to-face interactions through long meetings with clients became draining. I found myself better suited for the analytical and client servicing role away from client meetings. This meant that I could work on my own time, rely more so on myself for data gathering and paperwork, and keep client interactions at a distance (mostly emails or phone calls).

After that internship, I knew that I preferred non-client facing roles because of my strengths and how I was built methodically, not because I ever viewed myself as antisocial with regard to clients and team members or incapable of working in an associate planner environment. I had hoped that I could eventually take on a role that encompassed this side of the profession without having to climb the seemingly inevitable firm ladder to an adviser position.

It wasn’t until I started working with Lisa Kirchenbauer that I was able to hone in on those skills and methodology, assume the role of an operations associate—and now analyst—and create a thorough career path for my position at Omega Wealth Management.

How to Create an Operations Career Path

Operations and client-service roles should be recognized as a separate career path at financial planning firms due to the complexity and skill set required to fill these roles. At our firm, the operations role, in general, includes:

- All money movement

- Account transfers and maintenance

- Client information management

- Revenue invoicing

- Fee collection and analysis

- Technology oversight

- Trading

A career path for an operations position would look similar to an adviser position.

First, you would start out as an operations associate with some experience in the larger financial services industry.

Second, you would move up to an operations analyst within one to three years of experience at the firm and mastery of some of those previously mentioned responsibilities.

Third, you would be promoted to operations manager within three to five years of experience at the firm—not only have you mastered all of your responsibilities by this point and gained some exposure to other functions of the firm, but you also have obtained some kind of professional certification (CFP®, CMA®, RP®, etc.).

The fourth and final promotion would lead to a director of operations role, which would include a broader involvement in planning analysis, five to seven years at the firm, and require a master’s degree in finance-related studies.

Every firm has a different set of responsibilities for their operations and client-service employees. For example, the technology and fee revenue responsibilities associated with the operations role at our firm might not be the same for other firms.

We believe it is in everyone’s best interests to take the time to craft a proper career path that makes sense to both the firm and the operations employee. A defined career path is key to separating out the operations role away from something to be seen as a “stepping stone” to the next adviser, especially if it is not in the employee’s best interest to become an adviser in the future.

Andrew Mehari is an operations analyst at Omega Wealth Management. He has been in the profession for two years. In 2014 he graduated from Virginia Tech’s Pamplin School of Business where he completed the Financial Planning Program track.