Journal of Financial Planning: September 2013

Jerry A. Miccolis, CFP®, CFA, FCAS, is a principal and the chief investment officer at Brinton Eaton, a wealth management firm in Madison, New Jersey, and a portfolio manager for The Giralda Fund. He co-authored Asset Allocation For Dummies® and numerous works on enterprise risk management.

Marina Goodman, CFP®, is an investment strategist at Brinton Eaton and a portfolio manager for The Giralda Fund. She has been working to bridge the gap between research and practice to improve the portfolio optimization process.

As we write this column in mid-June, domestic stock indexes are in rarefied air. The S&P 500 has, on a total return basis, almost tripled since its March 2009 low point, marking an annualized return of about 26 percent.

That makes some investors more nervous than others. The wariest are expecting the inevitable correction, or worse, to be right around the corner (indeed, it already may have occurred by the time this column reaches print). Others who focus more on current economic fundamentals—seeing improving earnings, labor, and housing figures—and are sanguine about the Fed’s ability to engineer a graceful exit from its historically accommodative policies, believe this is just the beginning of a long bull market. The disparity of opinions in the face of the same facts is nothing new; it will always be the case when we talk about the future.

What we find a bit disturbing, though, is the distorted view of the recent past. We are aware of a number of investors who, looking back over these last four-plus years, believe their diversified portfolios have somehow deprived them of some wealth creation. For most investors, even the most aggressive, their portfolios have had allocations to asset classes other than domestic equities—things like international equities, bonds, real estate, commodities, market neutral/absolute return strategies—and, as a group, these asset classes have recently underperformed U.S. stocks. Some portfolios also have included explicit risk-management devices (puts, collars, hedges, etc.).

Never mind that these diversified and well-risk-managed portfolios have enjoyed returns well above long-term averages and far above any reasonable expectations from a financial planning perspective. They have underperformed the S&P 500. With the benefit of hindsight, these investors are plagued by the notion that they have left something on the table.

Now, this does not describe even the majority of investors. Most see the big picture. They understand that proven portfolio risk management techniques, such as proper diversification, pay off in the long run. They appreciate that they don’t need to fully participate in every last percentage point of bull markets if they can avoid a commensurate portion of the intervening bear markets. They correctly view successful investing as a marathon, not a sprint.

As professional financial advisers, we can be thankful that this describes the majority of our clients. However, some investors cannot get past ruing their perceived opportunity cost. So, we thought we’d compile a few facts that might help you illuminate the way for those who may be having trouble seeing the larger landscape.

Some Basic Facts

Most of these facts are grounded in simple arithmetic. Your clients may not view the arithmetic as simple, but the irrefutable truth of these facts should give us professionals the fortitude to persist in our explanations to clients that what we are doing for them is in their best interests, even though it may not be immediately evident.

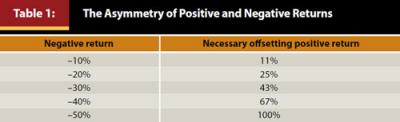

The first demonstration is one you likely have seen before. It highlights the asymmetry of positive and negative returns. A negative return of a given size is more harmful than a positive return of the same size is helpful. If you start with $100, a 10 percent loss (to $90) requires a subsequent 11 percent gain ($100/$90 – 1) to get back to break-even. The larger the percentage, the more pronounced the asymmetry, as Table 1 shows.

Given this asymmetry, the implication should be clear that a portfolio risk management device that minimizes extreme movements in either direction equally will lead to greater wealth creation over time than a portfolio without such a device. The “device” can be as simple as routine asset class diversification. It also can be more complicated, using derivatives, for example, to establish cost-effective dampening of portfolio movements.

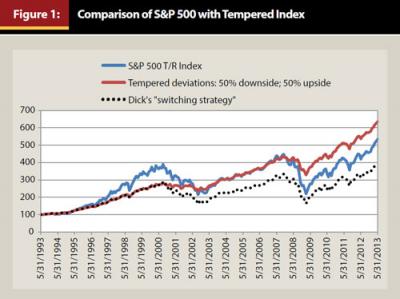

If this wealth-creation implication is unclear, the second demonstration should help remove all doubt. Let’s use the S&P 500 Index to make the point, although any index with peaks and troughs (in other words, any real-life index) would do. In Figure 1 we plot (in blue) the S&P 500 monthly total return index over the last 20 years. The average monthly return of the index over this period was 0.80 percent; its monthly standard deviation was 4.37 percent. We also plot (in red) the index if we temper by 50 percent the upside and downside monthly deviations from the average return. The average monthly return of this tempered index remains 0.80 percent, but its standard deviation is now 2.18 percent, half the original.

Let’s make a few observations from Figure 1. It is clear that an investment that behaved like the tempered index would have resulted in substantially more wealth over the 20-year period, relative to the S&P 500. It is also clear that the outperformance is entirely attributable to periods when the S&P 500 is in decline. A corollary to this second observation is that when the S&P 500 is steadily rising, the tempered index falls significantly behind. We started the comparison in the early 1990s to highlight this fact—through mid-2000, the tempered index grows by 170 percent cumulatively, while the untempered S&P 500 grows 264 percent.

Impatience Can Be Costly

Suppose, in mid-2000, Dick, an investor with results similar to this tempered index, became so disenchanted with his perceived opportunity cost over the first seven years that he abandoned his risk-managed portfolio in favor of one that simply followed the untempered index. His subsequent return over the next 13 years would have been a cumulative 47 percent, while his sister, Jane, who stayed faithful to the tempered approach, enjoyed a cumulative return of 135 percent over the same period. Jane, of course, ended up much wealthier after the full 20 years, having seen a cumulative growth of 536 percent compared to her brother’s 298 percent. In dollar terms, Dick grew his original $100,000 portfolio to $398,000 (see dotted line on Figure 1), while his sister, who also started with $100,000, grew her portfolio to $636,000. Dick deserted a proven, time-tested risk management approach simply because it wasn’t needed, in retrospect, over the short term. Sadly, his adviser was not persuasive enough to protect him from himself.

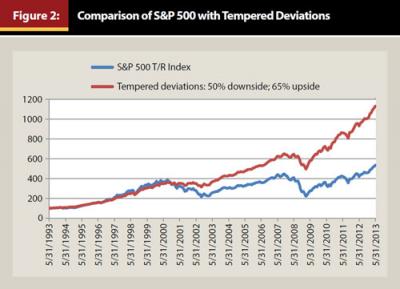

Now, a risk management device that tempers the portfolio’s movement equally in either direction is not particularly efficient. A more desirable result is to limit the downside more than the upside. Indeed, a number of hedge fund-like strategies have as their objective to deliver “equity-like returns” of two-thirds of the S&P 500 at one-half the volatility.

In Figure 2 we show a comparison similar to Figure 1, but we assume the tempered index captures 50 percent of the downside deviation and 65 percent of the upside.

A Jane-type investor in this case would have grown her $100,000 original investment to $1.13 million. Even in this example, note how through the first seven years, an investment in the non-risk-managed S&P 500 would have done better. This typically will be the case when the untempered index is in relentless upswing. We have seen recent examples of investors who have grown impatient with risk-managed investing when facing a similar situation.

Our bottom line is this: Portfolio risk management is a powerful wealth-building tool for investors with the foresight to appreciate its potency and the patience to let it work.

As trusted advisers, we have a duty to impart such foresight to our clients who lack it and to counsel such patience when it would otherwise falter. We would be interested to hear of your success stories in this regard. If we receive a critical mass of these stories, we’ll report on them in a subsequent column.