Journal of Financial Planning: November 2012

Mark W. Riepe, CFA, is a senior vice president at Charles Schwab & Co. Inc. and president of Charles Schwab Investment Advisory in San Francisco, California.

As I’m writing this (early September 2012), bond mutual funds continue on a roll when it comes to gathering assets. These positive flows have been happening despite the talk for many years of a bond bubble forming. Given that the 10-year Treasury yield is at 1.68 percent (as of September 6), it’s a reasonable expectation that interest rates are more likely to go up instead of down in the future. When that happens, how quickly will bond fund investors flee? The structure of the question presumes some sort of relationship between bond fund returns and cash flows into and out of funds. Does that relationship exist?

Investigation of Bond Fund Asset Flows

To shed light on these questions we focused on two categories of bond funds: high yield and intermediate term. These were chosen because the categories have long histories, lots of funds, and are owned (I believe) by different types of investors. I think of high-yield fund shareholders as more active and motivated by tactical considerations when deciding to get in or out of a fund. The intermediate bond category is more likely to be populated by shareholders who have a longer-term, strategic mindset when making their investment choices. For these investors, the intermediate-term fund represents a core holding tied to a risk preference or desire for diversification from stocks, whereas the high-yield investor has more of a “high yield is cheap, I want to get in” motivation or “spreads are too narrow, it’s time to get out.”

Given these admittedly simplistic profiles, how would we expect these shareholders to behave as returns inevitably fluctuate? My view is that deep within virtually all investors (individual and institutional alike) there’s a psychological predisposition toward return chasing (diving in when returns are good and fleeing when returns turn south). Bond fund investors are no different, and that means I expect there will be a positive correlation between returns and flows for both categories. However, given the more short-term mindset of the high-yield investor, the correlation will likely be stronger with high-yield funds than it will be with the intermediate-term bond category.

To test this theory, we constructed a series of monthly net asset flows for all mutual funds within the high-yield and intermediate-term categories using classifications and assets under management data from Morningstar. The data on individual funds were aggregated into category totals. The category totals were then correlated with the monthly returns of the Barclays Aggregate Index (for intermediate bond) and the Barclays U.S. Corporate High Yield Index (for high yield). The period for the analysis was August 1992 to July 2012. There’s nothing magical about the start date; we wanted a common period for the two categories and we went as far back as we could.

Exchange-traded funds (ETFs) weren’t taken into account for two reasons. First, we wanted to keep the series pure. Second, bond ETFs have gained meaningful assets only in the last few years and are still a small percentage of total bond fund assets.

Results

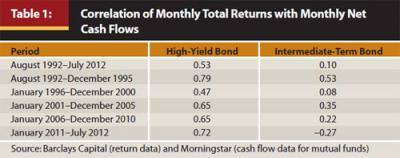

Table 1 shows the results for the full period as well as for arbitrary sub-periods.

Whether looking at the full period or the sub-periods, the results are consistent with the hypotheses described above—net flows are positively correlated with returns and the correlation is far more positive with the high-yield fund category than with the intermediate-term bond fund category. The reported correlations are probably too high, given the method of estimating the net cash flow for the funds implicitly assumes that the cash flow is taken out at month end. Therefore the focus should be not so much on the precise number in the table but the difference between the two categories and the sign of the coefficient.

I expected a certain degree of choppiness from both series for the sub-periods because of the smaller sample size, but those results strike me as remarkably stable for high yield and much choppier for intermediate-term bonds.

Analysis

It’s always at least a little dangerous to look at the correlation between two variables and then draw grand conclusions, but here goes. High-yield bond fund investors appear to have a steady focus on performance throughout all sorts of different economic and interest-rate environments. To illustrate this point more vividly, the high-yield category had a positive net cash flow in only 8 of the 64 months with a negative total return to the high-yield index. My colleague, Kathy Jones, points out that this also could be explained by the fact that liquidity in high-yield bonds is relatively thin compared to intermediate-term bonds. In some cases, high-yield managers may actually be forced to sell into a weak market to meet redemptions, which in turn leads to poor returns, which in turn leads to more selling.

Intermediate-bond fund flows are a more nuanced and confusing story. The full period correlation of 0.10 indicates an extremely mild positive correlation. The first sub-period was dominated by 1994, when rates persistently rose and in many of those months the category experienced net redemptions. The next sub-period exhibited steady and positive inflows that were impervious to interest-rate movements, with the exception of a few months around the year 2000. This may have been because longer-term rates were generally declining over this period. The next two periods were relatively normal.

The most recent period for intermediate-term bonds is an anomaly. It’s a short period so the statistics themselves need to be viewed skeptically, especially because the results seem to be driven by a few outliers. For example, in August 2011 there was $4.7 billion in net outflows, but returns were a strong 1.5 percent. This was probably due to people moving money into more safe categories because of the U.S. Treasury debt default/downgrade crisis, even though returns remained positive. There were also big outflows in January and February 2011, driven, I suspect, by an anticipation of rates increasing (which never came to pass).

Key Takeaways

Do these results tell us anything about how bond fund investors will react when rates start to increase?

I think they do. High-yield investors, I suspect, will be the quickest to pull the trigger and redeem shares. That expectation needs to be tempered, though, with consideration of the fact that high-yield returns are not driven solely by interest-rate movements. High-yield returns have been correlated with equity returns in the past. When rates rise, if they are accompanied by a rise in stock prices, it wouldn’t be surprising if the final impact on flows is more muted.

As for intermediate-term bond fund holders, the question appears to depend on at least two factors. First, the severity of the increase or perceived increase in rates is likely to play a role. If rates increase month after month, as in 1994, some outflows appear to be likely. If these investors get worried about an expected increase in rates for whatever reason, they’ve also exhibited a willingness to move money out of these funds.

Second, demographics should be taken into consideration. The baby boomers are a lot older than they were in 1994. Given their age and the degree of wealth they control in the country, it is possible the individual investor space is more conservative than it was in the past, and therefore more willing to stick with the sorts of core bond funds that often fall into the intermediate-term category—even in the face of rising rates.

It’s not obvious how to empirically test these propositions, but given the variability in the sub-period results and the low correlation over the full period, it is hard to draw anything definitive from these numbers. If one thing is clear, the flows to intermediate-bond funds are driven by a lot more than just recent returns.