Journal of Financial Planning: November 2012

Executive Summary

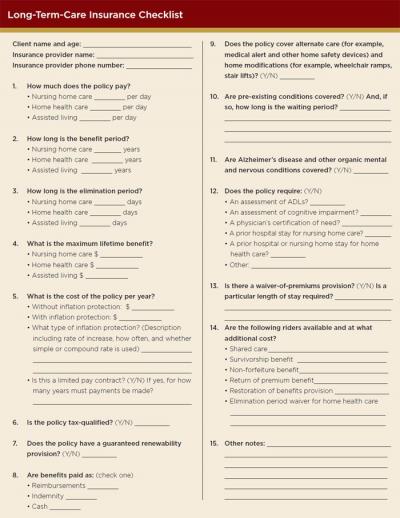

- This article provides information on the current state of the long-term-care insurance industry and the likelihood of requiring long-term care, and discusses the benefits and costs of long-term-care insurance.

- It provides data on the current and expected future costs of various types of long-term care, and compares data on the current cost of long-term-care insurance by age and geographic area.

- The article provides statistics on the length of care conditional on admittance to a nursing home: overall, by gender, and by age, and discusses a variety of important features that should be considered when choosing a long-term-care policy.

- Lastly, the article examines alternatives to long-term-care insurance, such as Medicare, Medicaid, and self-insurance.

Karyn L. Neuhauser, Ph.D., an associate professor of finance at Lamar University, has held academic appointments at the George Washington University and the State University of New York (Plattsburgh). She worked as a CPA for five years before earning her doctorate from Louisiana State University. Her research has been published in the Journal of Real Estate, Finance, and Economics, the Journal of Financial Research, and the International Journal of Managerial Finance.

Long-term care (LTC) encompasses the wide range of services that may be needed when a person suffers from a prolonged illness, cognitive impairment, or other disability. These services may be provided in one’s own home through home health agencies, in an assisted living facility, or in a nursing home.1 This article analyzes the benefits and costs of protecting against these expenses through long-term-care insurance, explains important features that should be considered when choosing among LTC insurance policies, and discusses alternatives to LTC insurance.

The most frequent purchaser of LTC insurance is married, between the ages of 55 and 64, and has annual gross income of $75,000 or more (America’s Health Insurance Plan). LTC insurance is particularly relevant for middle- to high-income couples when a sizable portion of their joint income stream is expected to disappear when one spouse dies (for example, a pension that terminates upon death). This is true because the surviving spouse is likely to be dependent on their joint wealth as a major source of future consumption (Pauly 1990). Therefore, they may wish to insure against the risk that LTC expenses will seriously diminish their pool of wealth. Despite the fact that LTC insurance is more frequently purchased by married couples, single people are more at risk of requiring professional LTC because they cannot rely on a spouse to provide care. LTC insurance is also useful when the insured, whether married or not, wishes to protect bequests to heirs.

The main function of LTC insurance is to protect the assets of an individual who, at some point in life, requires long-term care. In 2010, the total spent on home health care, assisted living facilities, and nursing homes was $213.3 billion (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services). Yet, long-term care remains one of the largest uninsured financial risks facing the elderly in the United States, with only 10 percent to 12 percent of older Americans covered by LTC insurance (Brown and Finkelstein 2007).

Benefits of Long-Term-Care Insurance

Estimates suggest that about 70 percent of people over age 65 will require some form of long-term care at some point in their life (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2010). While family and friends are the sole caregivers for the majority of the elderly, about 40 percent will enter a nursing home at some point in their lives and almost 10 percent of those who enter a nursing home will stay for five years or more (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services). Although many people think of long-term care as affecting only those in their senior years, 40 percent of people currently receiving long-term-care services are between the ages of 18 and 64. However, when it comes to the most expensive type of care (nursing home care), 86 percent of users are over 65 (Kaye, Harrington, and LaPlante 2010).

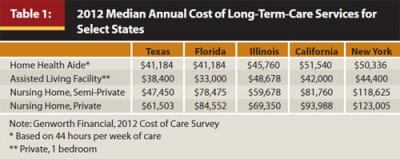

In 2011, the national average cost of a semi-private room in a nursing home was $75,555 annually (John Hancock Life Insurance Company 2011). Table 1 shows the current annual costs for four separate categories of long-term care by state for the five most populous states.2 One striking observation is that the median annual cost of a nursing home ranges from less than $48,000 for a semi-private room in Texas to over $123,000 for a private room in New York.

Most long-term-care policies are reimbursement policies that cover LTC expenses incurred up to a per-period limit. The limit typically ranges from $50 to $500 per day, which translates to $18,250 to $182,500 per year. Any costs above that are paid out of pocket.

Almost all LTC policies sold today are tax-qualified plans. This means the benefits received are tax-free as long as they do not exceed the greater of actual costs or $310 per day. In addition, the long-term-care insurance premiums and any out-of-pocket costs for long-term care can be included as medical expenses if the policyholder itemizes deductions.3 However, due to the restrictions and limitations, the tax deduction for LTC premiums is usually not a strong motivation for the purchase of LTC insurance. An exception is self-employed taxpayers who can usually deduct any LTC premiums paid for themselves, their spouses, or dependents that are paid through an employer-sponsored plan as a trade or business expense.

The benefit period is the amount of time the policy will pay out from the point of claim. Typical benefit periods range from two years up to unlimited or lifetime policies. According to the American Association for Long-Term Care, about two-thirds of new policies sold in 2007 had three-, four-, or five-year benefit periods.

Most long-term-care policies offered today use a “pool of funds” or “pool of money” concept, which means they multiply the daily benefit amount purchased by the number of days in the benefit period and this total “pool of funds” is available to the policyholder over any period. For example, if a five-year, $200 per day policy is purchased, the pool is equal to $365,000. If only $100 per day is used while receiving long-term care, the benefits will last for 10 years rather than five years. Or if $200 per day is used but care is only required five days a week, the benefits will last for seven years.

The median length of stay in a nursing home is one year for men and 1.4 years for women. However, the average length of stay is 2.1 years for men and 2.4 years for women. In addition, 44 percent of residents have been there less than a year while almost one-third have been there one to three years, and one-quarter have been there over five years. However, this exaggerates the typical time spent in a nursing home because longer-term residents are oversampled. For instance, a person who stays five years has a 20 times greater chance of being included in the sample than a person who stays three months.

Kelly et al. (2010) examined a representative sample of 1,817 Americans over age 50 who died between 1992 and 2006, and found that 27 percent were residing in a nursing home at the time of death. The median length of stay before death was five months and an average stay was 14 months. They also report that 53 percent of those residing in nursing homes died within six months, 65 percent died within one year, and 75 percent died within two years of admission. This seems to suggest that a long-term-care policy that covers three-to-five years of LTC may be more than adequate for most people. However, when selecting the length of coverage, it is important to remember that nursing home stays are often preceded by periods of home health care or stays in assisted living facilities.

While these statistics are useful in estimating the typical duration of a nursing home stay, the LTC insurance buyer should also consider personal risk factors. For example, if both the buyer’s parents lived into their mid-90s and needed care for several years, or if the buyer’s family has a history of Alzheimer’s disease, this should be factored in when estimating the length of care needed.

Kemper, Komisar, and Alecxih (2006) project the aggregate need for long-term care by people over age 65 and argue that the typical person will require almost three years of long-term care, including at home, assisted living, and nursing home care. Over one-third will require a stay in a nursing home at some point and one out of every 20 will end up spending five years or more in a nursing home.

Despite studies that show women are two to three times more likely than men to require LTC and that, on average, they require care for a longer period, premiums usually do not vary by gender. However, LTC insurance is purchased about equally by men and women even though it is generally a much better buy for women than for men (Brown and Finkelstein 2007).

Kemper et al. project that 50 percent of people will incur no out-of-pocket expenses either due to lack of need for LTC (31 percent), exclusive reliance on family and friends (12 percent), or costs paid entirely with public funds (7 percent). For those who receive some type of formal care, the average out-of-pocket expenses were approximately $36,700 in 2005 dollars. But these expenses will not be shared evenly among care recipients: 32 percent will spend less than $25,000, 11 percent will spend $25,000 to $100,000, and 7 percent will spend $100,000 or more of their own funds.

Costs of Long-Term-Care Insurance

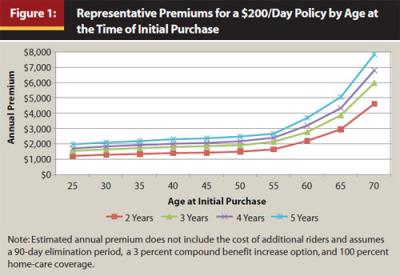

The average buyer of LTC insurance is 57 years old and pays less than 3 percent of gross income in premiums. Figure 1 shows the typical premiums that might be paid on a policy that provides up to $200/day for periods of two, three, four, and five years. As shown in Figure 1, the cost of long-term-care insurance depends on the age of the policyholder at the time of the initial purchase; the longer a person waits to buy LTC insurance the higher the premiums they must pay.

Figure 1 also shows that there are discounts when purchasing additional years of benefits (for example, a four-year policy does not cost twice as much as a two-year policy). This is presumably because of the low percentage of policyholders who require care beyond a couple of years, as noted earlier.

The change in premiums over the age intervals 55 to 60 and 60 to 65 is around 30 percent to 40 percent. Premiums then increase by about 55 percent between age 65 and 70. This may explain why most people who purchase LTC insurance do so in their late 50s. With a three-year policy, a 55-year-old buyer will pay around $1,730 less than a 65-year-old buyer. Even though the 55-year-old pays premiums of $21,400 over the 10 years that are avoided by the 65-year-old, the premium savings in later years will allow the 55-year-old to recoup this additional cost in 12.4 years and the 55-year-old is insured against an early need for LTC.

A serious risk of waiting too long to buy LTC insurance is ineligibility, because the likelihood of suffering from a pre-existing condition that precludes insurability increases as the would-be buyer ages. Murtaugh, Kemper, and Spillman (1995) estimate that 12 percent to 23 percent of people age 65, and 20 percent to 31 percent of people age 75, will be unable to obtain a private LTC policy because of medical reasons.

In most cases, policies are sold as level premium contracts, meaning that premiums cannot increase at a later date due to an increase in the policyholder’s age or a decline in the policyholder’s health. With level premium contracts, the premiums can rise only if the state approves an increase for an entire class of policyholders.

Unfortunately, because insurers seemingly miscalculated the true costs of providing LTC coverage (overestimating how many policyholders would allow their LTC policies to lapse, underestimating LTC cost increases and policyholder usage, and overestimating investment rates of return), a number of steep premium hikes have been reported over the past few years.4 Faced with large premium increases, some policyholders are tempted to let their LTC insurance lapse, but doing so means forfeiting the premiums that have already been paid. If the policyholder is unable or unwilling to pay the new, higher premiums, a better alternative is to reduce the number of years of coverage, the daily amount of coverage, or the inflation adjustment, or increase the elimination period to bring down the premiums to an affordable level. In addition, many states allow policyholders who experience large rate increases to stop paying premiums and retain coverage equal to the premiums already paid.

Comparing Long-Term-Care Insurance Policies

When recommending the purchase of LTC insurance, the financial health of the insurer, or counterparty risk, is of paramount importance. Ideally, the insurer should have not only a high financial rating and an excellent track record in the business, but also a history of timely payment of claims without excessive increases in premiums. While the insurer’s financial strength, the cost of the insurance, and the amount and length of coverage are all clearly important, other policy features also may be useful to clients.

One important consideration is whether the benefits are reimbursements, indemnity benefits, or cash benefits. With reimbursements, a bill is submitted and the policyholder is reimbursed for the amount of the bill or the daily limit, whichever is less. With an indemnity policy, a bill is submitted and the policyholder receives the daily limit, even if the bill is less than the limit. With a cash policy, the policyholder receives the daily limit once it has been established that the policyholder needs long-term care. Importantly, a bill is not required with this type of policy and that means the long-term care can be provided by anyone (for example, a relative or friend) and the money can be used to pay the caregiver or for any other purpose. Because of their greater benefits, indemnity policies and cash policies are generally more expensive than reimbursement policies. If the buyer expects to receive care from a friend or relative, a cash policy may be worth the added expense because of the flexibility it provides.

Some of the newer policies being offered pay a monthly benefit as opposed to a daily benefit. This provides better coverage if LTC expenses fluctuate from day to day. For example, instead of coverage of up to $200 per day, the client has access to $6,000 per month ($200 x 30). If long-term-care needs are sporadic, $300 worth of services may be needed one day and only $50 the next. In this case, the client would be better off with the monthly benefit plan.

Another important factor is the elimination period—the period from when the claim is triggered to when the policy starts to pay benefits. In a way, it is analogous to a deductible. With most LTC policies, a claim is triggered by either a cognitive impairment requiring substantial supervision or loss of two “activities of daily living” (ADLs)—bathing, dressing, personal hygiene and grooming, ambulation, functional transfer (for example, getting in and out of bed), continence, and self-feeding.5 Typical elimination periods range from 0 to 365 days, with 90 days being the most common. Obviously, a shorter elimination period reduces out-of-pocket costs, but it also increases the premiums. Some policies calculate the elimination period using calendar days while others count only the days service was received. Also, some policies have a once-in-a-lifetime elimination period while others require the policyholder to pay the costs incurred during the elimination period each time long-term care is required. Separate elimination periods may be required for nursing homes and home health care or the elimination period may be combined for all services. Because many people try home health care before going to a nursing home facility, the combined elimination period is an attractive feature.

Over three-quarters of LTC policy buyers are now choosing some form of inflation protection. While a policy that adjusts the coverage for inflation typically costs 40 percent to 120 percent more than one without inflation adjustments, the average cost of a nursing home has risen at a compound annual rate of about 5.7 percent over the last 25 years, making inflation protection critical for most buyers. A comparison of the projected median annual costs of long-term-care services in 20 years, shown in Table 2, highlights the importance of protecting against rising costs when designing an LTC plan and also may be useful in convincing clients of the need for LTC protection.

There are basically five strategies when it comes to dealing with rising costs. First, if the policyholder is 80 or older, ignoring the effects of inflation and simply purchasing a policy that has ample coverage of current costs may make sense.

Second, a guaranteed purchase option may be used. In this case, the policy does not automatically adjust for inflation, but policyholders are allowed to increase coverage every few years, regardless of their health. However, the policyholders may pay higher premiums for these extra benefits based on their age when they buy them. This choice is often preferred by policyholders in their 70s.

The third option is known as simple inflation, and boosts the original benefit by 5 percent each year, which results in a doubling of the benefit every 20 years.6 This option is often recommended for policyholders over 65. The fourth option is compound inflation (as shown in Table 2) which increases the daily benefit by 5 percent compounded annually and results in a doubling of the benefit every 14.2 years. The compound inflation protection option is typically recommended for those under age 65. To further emphasize the difference in coverage between the third and fourth options, a policy that initially covered $200/day with a 5 percent inflation adjustment will cover $400/day using simple inflation versus $530/day using compound inflation after 20 years.

The final way to protect against inflation is to buy a policy without inflation protection but with a daily benefit well above the current per-day cost of care in the policyholders’ geographic target area. However, this option may be prohibitively expensive for many individuals.

Almost all policies sold today cover in-home care and assisted living as well as nursing home care.

However, with some policies, the home health care benefit is only half the size of the nursing home benefit, so a $200/day policy will only pay up to $100/day for home health care or assisted living. Other policies pay the full amount for all types of care. This is an important distinction because most people prefer to remain at home if at all possible and, in fact, many buyers cite in-home care coverage as the primary reason for buying an LTC insurance policy.

Most policies also include an alternate care benefit that covers items such as in-home safety devices, medical alert devices, and home-delivery of meals. Most policies also cover necessary equipment and home modifications, such as wheelchair ramps, stair lifts, and grab bars. In addition, a good policy will include homemaker services that cover the cost of having someone come in to cook and prepare meals and do laundry and light housekeeping.

A “waiver of premiums” is a policy feature that allows policyholders to stop paying premiums while they are receiving benefits. These waivers usually begin after the elimination period has been satisfied. It is important to know whether the waiver applies only to nursing home care or to any type of long-term care. A joint waiver option means that the premiums on both spouses’ policies are waived if either spouse is receiving care.

To reduce the risk of future premium increases, some policyholders choose limited pay contracts that allow for the full payment of premiums over a limited period. The most common are single-pay, 10-year, 20-year, and pay-until-age-65 plans. The main advantage is that once the last payment is made, the policyholder no longer has to worry about premium increases. Some of these plans also include a rate guarantee that protects the policyholder from increases throughout the payment period. The main problem with this option is that the premiums required may be unaffordable for many buyers. For example, a 50-year-old may pay premiums that are 150 percent to 190 percent higher with a limited pay plan compared to a lifetime pay plan.

Realizing that couples often care for each other in the home if they are able, most companies offer spousal discounts of 15 percent to 25 percent when a person is part of a couple or 20 percent to 40 percent when both members of the couple apply and are approved for coverage. Marriage is usually not a requirement for the couples’ discount. In most cases, opposite sex or same sex couples who have cohabitated for a certain length of time qualify for the discount. The latter discount is often contingent upon both members of the couple purchasing exactly the same coverage. This may be a good idea if both spouses are close in age and income but may not be appropriate otherwise. It is also important to know whether the premiums will change when one of the spouses dies. Most of the time, the premium for the remaining spouse remains fixed at the discounted level, but in some cases it increases, often considerably.

Other optional riders may be obtained at additional cost. Survivorship, elimination period waivers for home health care, shared care, restoration of benefits, and return of premium are frequently offered in LTC insurance plans.

A survivorship benefit, which usually adds about 10 percent to the cost of an LTC policy, waives the surviving spouse’s premiums for life when one spouse dies, provided that both spouses have held their policies for a minimum period (usually seven or 10 years) without any claims. This rider is most useful when one spouse is significantly older than the other, especially when the older spouse is the main source of income.

A waiver of the elimination period for home health care can usually be added to a policy for about 8 percent to 15 percent over the base policy cost. This option means that coverage for home health care begins immediately upon requiring such services. Given its modest cost, this option deserves serious consideration.

Shared care, which usually adds about 10 percent to 20 percent to the base cost of a policy, is a benefit that may be useful for married couples. It allows either spouse to use the benefits of the other spouse when they have used all the benefits of their own policy. Given the low probability of both spouses requiring extended periods of care, this may be an option worth paying for.

A non-forfeiture benefit, which usually adds about 10 percent to 25 percent to the base policy cost, allows a policyholder who lets the policy lapse after at least three years of premium payments to be reimbursed for care equal to the greater of 30 times the daily benefit amount or the total premiums that were paid prior to the lapse. A restoration of benefits option restores policy benefits to their original maximum if the policyholder comes off a claim for 180 consecutive days. At some companies, this option is included in the basic policy. At other companies, this option will add about 5 percent to the cost of the basic policy.

The return of premium benefit is one of the most costly, usually adding about 30 percent to 50 percent to the base cost of an LTC policy. However, the advantage is that all premiums paid are returned to the named beneficiary upon the death of the policyholder if the policy has not been used to pay for long-term care. In some cases, even if the policy has been used, the premiums paid less any claims reimbursements are paid out to the beneficiary.

It is important that the policy has a guaranteed renewability provision and, because the 1996 Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) legislation requires this for all federally tax-qualified policies, virtually all do. This means the policy cannot be canceled as long as the premiums are paid on time. However, premiums can still be increased as long as the increase affects an entire group of policyholders.

Lastly, the policy also should be checked for exclusions. Many policies exclude pre-existing conditions for a period, usually no greater than six months. Many policies exclude mental and nervous disorders, substance abuse-related illness, and intentionally self-inflicted injuries. A policy that excludes mental and nervous disorders is especially risky because Alzheimer’s disease or other types of dementia will affect many people as they age.

Alternatives to LTC Insurance: Personal Health Insurance, Medicare, and Medicaid

Many people erroneously believe that Medicare, Medigap, or their personal health insurance will pay for their long-term-care needs. Most personal health insurance plans only cover skilled, short-term medical care during recovery from an illness or injury. Skilled care is designed to treat a medical condition, typically following a hospital stay, and is normally provided by skilled nursing staff. However, many elderly people require only custodial care, which entails assistance with ADLs or supervision necessitated by serious cognitive impairment.

Medicare pays only for medically necessary skilled nursing facilities, hospice, or home health care, and only for a limited amount of time. A person must meet all three of the following conditions for Medicare coverage: (1) they have had a recent hospital stay of three or more days, (2) they have been admitted to a Medicare-certified nursing facility within 30 days of that hospital stay, and (3) they are deemed to require skilled nursing care on a daily basis. Even if the person meets all these requirements, Medicare will only pay for some of the costs and only for a maximum of 100 days. Specifically, Medicare will pay 100 percent for the first 20 days. For the next 80 days, Medicare requires a deductible of $141.50 per day, which is typically covered by Medigap insurance policies. After 100 days, all costs are borne by the nursing home resident. In fact, most long-term care helps people with ADLs such as dressing, bathing, and using the bathroom. Medicare does not pay for this type of “custodial care.”

Medicaid is a state-based program supplemented with federal government funds that pays for certain health services and nursing home care for older people with low incomes and limited assets. Medicaid programs dominate the nursing home market; almost all nursing homes are Medicaid-certified and serve at least some Medicaid patients. In most states, Medicaid also pays for some home health care or adult daycare services, but this type of care is usually limited to no more than 28 hours per week. Medicaid does not cover the cost of assisted living facilities.

State requirements for Medicaid eligibility and services covered vary from state to state. Most often, eligibility depends on wealth (as measured by assets) and income. For middle- and high-income individuals, Medicaid will only pay once personal wealth has been virtually exhausted. In addition, if personal income is available, Medicaid will pay only the difference between the cost of care and personal income. Many people attempt to “spend down” their assets to state required levels or attempt to transfer their assets to family members to become eligible for Medicaid funding. Under the 2005 Deficit Reduction Act (DRA), states have the authority to examine a Medicaid applicant’s asset transfers during the past five years, known as the “look-back period.” If the asset transfers are deemed to be “disqualifying transfers,” Medicaid coverage is denied for a specified period, known as the “penalty period.” Moreover, in the current economic climate, the definition of disqualifying assets appears to be very broad (Cammuso 2010).

The DRA also authorized states to establish long-term-care insurance partnership programs. These programs encourage the purchase of private long-term-care insurance by individuals primarily by allowing them a dollar-for-dollar increase in the amount of assets they are allowed to retain when seeking Medicaid assistance for long-term-care costs. For example, as a general rule, to meet the financial qualifications for Medicaid funding, an individual cannot have assets that exceed $2,000. However, if an individual purchases a qualifying insurance policy under the state partnership program that provides $100,000 in long-term-care benefits, that individual would be allowed to hold assets equal to $102,000 and still qualify for Medicaid assistance. In addition, at death, these assets are exempt from the Medicaid estate recovery provisions. Currently, these programs are available in 39 states.7

As part of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act enacted in March 2010, the federal government attempted to create a public option for long-term care. The Community Living Assistance and Services and Supports (CLASS) program was designed to allow adults to purchase long-term-care insurance with relatively modest benefits from the federal government. However, the CLASS program was abandoned when a financially sustainable model for the program could not be created. Still, the Affordable Care Act’s Community First Choice Option, which provides financial incentives to states to use Medicaid funds to pay for home health care and adult daycare centers rather than nursing home care should make it easier for people with disabilities who are Medicaid eligible to remain at home.

Alternatives to LTC Insurance: Self-Insurance

According to Kemper, Komisar, and Alecxih (2006), only one in 20 people will incur long-term-care expenses of more than $100,000 in 2006 dollars. Given these odds and the high cost of LTC insurance,8 self-insurance is worth considering. Self-insurance eliminates overhead costs that must be covered when using an insurance company and allows the self-insured to draw down the funds at will if and when the time comes. However, self-insurance has a downside—it is likely to result in less-than-total coverage for those who ultimately incur large LTC expenses.

Self-insurance is more likely to be an option if the person in question is relatively young and self-disciplined. For example, suppose $2,000 is set aside each year for long-term care beginning at age 40. If the account earns an annual return of 5 percent, about $95,500 and $241,600 would be available at age 65 and age 80, respectively. The obvious risk of this strategy is that the person may require care before age 65, and even at age 65, the amount saved will cover less than one year of care given the projected costs shown in Table 2.

An alternative way to analyze self-insurance is to look at the rate that must be earned on the premiums to generate the same level of benefits.9 As an example, in Figure 1, the premium for a $200/day policy with a three-year maximum benefit, a 90-day elimination period, and 3 percent compound inflation adjustment is $2,770 at age 60. Given the inflation adjustment, the daily benefit will increase to $361.22 by age 80 (200 x 1.0320) and the total benefit will equal over $395,500 ($361.22 x 3 years x 365 days). If instead the $2,770 premium is set aside to cover LTC expenses, the funds would need to earn 17.8 percent annually for 20 years to generate the same $395,500. Using more realistic rates of return of 5 percent to 7 percent, the self-insurance option will only generate about $91,600–$113,600 by age 80 (which would cover approximately eight to 10 months of $361/day care).

Four caveats concerning this analysis are in order. First, the self-insurance option leaves any funds not used for LTC expenses available to the estate should long-term-care expenses be less than the amount accumulated in the self-insurance fund. Second, as noted earlier, under the LTC insurance option, the insured may be required to pay higher premiums to maintain this level of coverage. Third, the self-insured may find the saved funds to be woefully inadequate if long-term care is required at an age earlier than 80. Fourth, the tax effects of self-insured savings are ignored. This may be reasonable if we assume the self-insurance savings are held in a Roth IRA or similar vehicle. Otherwise, capital gains taxes on these funds will further reduce the amount available for LTC expenses. In addition, as noted by Cordell and Langdon (2009), the heirs of a wealthy individual who dies with a large pool of funds set aside for self-insurance of LTC risk may find those funds subject to estate taxes upon that individual’s death.

Clearly, the self-insurance option is inherently risky. Returns of over 17 percent are unlikely to be generated on a consistent basis and the amount saved under the more realistic 5 percent to 7 percent expected return may prove to be inadequate. Moreover, human nature being what it is, it is quite likely that the individual who sets out to self-insure LTC risk will find that the money gets diverted to satisfy other needs or desires.

Conclusions

Long-term-care funding is the most neglected aspect of retirement planning today. Cost is the most-often cited reason for not purchasing a long-term-care policy. If advisers recommend their clients buy the best policy available, many clients choose to go without any protection at all because of the high premiums. In such circumstances, a good policy, rather than the best policy, may be better than no policy at all (Ruffenach 2011). For example, even a $100/day policy with three years’ coverage and inflation protection can cover 85 percent to 100 percent of the costs of a home health aide or assisted living facility and 60 percent to 75 percent of the costs of nursing home care in a low-cost state. Supplemented with other income and assets, such coverage may be adequate for many people, provided it is part of a comprehensive plan for paying for long-term care.

Armed with the above information, a good starting point is to discuss the general probabilities and costs of long-term care to make clients aware of their personal risk exposure. From there, a discussion of a specific plan for dealing with this risk may naturally ensue.

Endnotes

- A recent examination of new LTC claims found a roughly even split across these three types: 31 percent for in-home care, 31 percent for assisted living, and 38 percent for nursing home care (American Association for Long-Term Care Insurance 2010 Sourcebook).

- The chosen states are generally representative of the range of costs across all 50 states. Notable exceptions at the lower end are Oklahoma, Missouri, and Louisiana with median annual costs for a private nursing home room of $53,597, $55,480, and $56,721, respectively, and at the higher end are Connecticut and Alaska with median annual costs for a private nursing home room of $145,818 and $232,500, respectively.

- These expenses are tax deductible up to certain age-based limits and to the extent they exceed 7.5 percent of adjusted gross income (AGI). The limits for 2012 are $350 for ages < 41, $660 for ages 41–50, $1,310 for ages 51–60, $3,500 for ages 61–70, and $4,370 for ages > 71 as of the end of the tax year. For tax years after 2012, the 7.5 percent limit will rise to 10 percent. Thirty-two states also permit some form of tax deduction for the purchase of LTC insurance. See www.aaltci.org/long-term-care-insurance/learning-center/tax-for-business.php#individual.

- In October 2010, John Hancock Financial requested an average increase of 40 percent in premiums for about 850,000 of its 1.1 million LTC policyholders while AIG, MetLife, and Lincoln National applied for increases ranging from 10 percent to 40 percent in one or more states (Tergensen and Scism 2010). In addition, many companies, including CNA Insurance and Prudential, have recently announced they will no longer sell new LTC policies.

- In most cases, the ADL loss must be certified by a licensed health care practitioner as being expected to last at least 90 days.

- While 5 percent inflation adjustments are quite typical, some policies use lower rates such as 3 percent, 4 percent, or even the CPI to make the annual adjustments.

- Details on each of the 39 existing state programs may be found at www.longtermcareinsurancetree.com/blog/partnership-center.

- Brown and Finkelstein (2007) estimate that the typical 65-year-old purchaser of LTC coverage pays a load of 18 cents on the dollar if the policy is held until death. When policies that are allowed to lapse are included in their calculation, the average load increases to 51 cents on the dollar.

- For other approaches to the question of self-insurance, see Everett, Anthony, and Burkette (2005) and Gold, VanderLinden, and Herald (2006).

References

America’s Health Insurance Plans. “Who Buys Long-Term Care Insurance in 2010–2011?” www.ahip.org/AHIPResearch/.

Brown, Jeffrey R., and Amy Finkelstein. 2007. “Why Is the Market for Long-Term Care Insurance So Small?” Journal of Public Economics 91, 10 (November): 1967–1991.

Cammuso, Linda T. 2010. “The Medicaid Five-Year Look Back: The Gift That Keeps Giving.” FiftyPlusAdvocate.com (September 27). http://fiftyplusadvocate.com/archives/1706.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. 2010. National Health Expenditure Accounts (NHEA) Highlights.

Cordell, David M., and Thomas P. Langdon. 2009. “Long-Term Care Insurance and the High Net Worth Client.” Journal of Financial Planning 22, 1 (January): 32–33.

Department of Health and Human Services National Clearinghouse for Long-Term Care Information (July 14, 2010). www.longtermcare.gov.

Everett, Michael D., Murray S. Anthony, and Gary Burkette. 2005. “Long-Term Care Insurance: Benefits, Costs, and Computer Models.” Journal of Financial Planning 18, 2 (February): 56–68.

Gold, Joel I., David VanderLinden, and John S. Herald. 2006. “The Financial Desirability of Long-Term Care Insurance Versus Self-Insurance.” Journal of Financial Planning 19, 11 (November): 54–61.

John Hancock Life Insurance Company. 2011. “Cost of Care Survey” (April).

Kaye, H. Stephen, Charlene Harrington, and Mitchell P. LaPlante. 2010. “Long-Term Care: Who Gets It, Who Provides It, Who Pays, and How Much?” Health Affairs 29, 1 (Jan./Feb.): 11–21.

Kelly, Anne, et al. 2010. “Length of Stay for Older Americans Residing in Nursing Homes at the End of Life.” Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 58, 9: 1701–1706.

Kemper, Peter, Harriet L. Komisar, and Lisa Alecxih. 2005. “Long-Term Care Over an Uncertain Future: What Can Current Retirees Expect?” Inquiry 42 (Winter): 335–350.

Murtaugh, Christopher M., Peter Kemper, and Brenda C. Spillman. 1995. “Risky Business: Long-Term Care Insurance Underwriting.” Inquiry 32, 3 (Fall): 271–277.

Opiela, Nancy, Thomas H. Riekse, and Karen Henderson. 2006. “Designing the Ideal Long-Term Care Policy.” Journal of Financial Planning 19, 5 (May): 24–32.

Pauly, Mark. 1990. “The Rational Nonpurchase of Long-Term-Care Insurance.” Journal of Political Economy 98, 1: 153–168.

Ruffenach, Glenn. 2011. “Some Long-Term-Care Insurance is Better than None.” Wall Street Journal’s SmartMoney.com (Dec. 28).

Salter, John R., Nathaniel Harness, and Swarn Chatterjee. 2011. “How Retirees Pay for Current Health Care and Future Long-Term Care Expenses.” Journal of Financial Service Professionals 65, 1 (January): 88–92.

Tergensen, Anne, and Leslie Scism. 2010. “Long-Term Care Premiums Soar.” Wall Street Journal (Oct. 16).

U. S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2002. “National Nursing Home Survey: 1999 Summary.” (June).