Journal of Financial Planning: May 2015

On December 19, 2014 President Obama signed the Achieving a Better Life Experience, or ABLE Act, into law. The ABLE Act provides a vehicle for families to save for the future care of their child with special needs through an account made available by similar legislation for 529 college savings plans.

This article provides a brief history of the ABLE Act, an overview of the rules, a comparison with other savings options, and specific examples where ABLE accounts can typically be the most appropriate planning strategies.

Brief History of the ABLE Act

The concept of a tax-preferred savings vehicle for individuals with disabilities has been in the making for many years. It began in 2004, when a proposal drafted by a group, including this author, was placed in the final recommendations to President George W. Bush’s Committee on Intellectual Disabilities.

In 2007, Representative Ander Crenshaw (R-Fla.) sponsored the original proposal for a tax-free savings vehicle for individuals with disabilities and was the leading force behind the bill. Advocacy efforts from the National Down Syndrome Society and Austism Speaks helped build early momentum. It was a bipartisan effort that took many years to work through the system. As the bill progressed, some of the original plan benefits were reduced. These compromises impacted the ABLE account’s effectiveness for some individuals.

The U.S. Treasury is in the process of writing the regulations, however many states have taken the initiative to begin drafting the provisions to implement the plan in their own state. The Treasury is not discouraging states from enacting their legislation, and it intends to provide “transitional relief” to states whose programs don’t comply with federal guidelines, including “sufficient time” to implement necessary changes, according to the ABLE National Resource Center. Because the Treasury is providing flexibility to states in drafting their own plans, it is likely that the provisions of the ABLE Act will vary state to state. Therefore, when plans become available later this year, planners should use caution in recommending them to their clients.

Families Planning for a Child with a Disability

One of the greatest benefits of the ABLE Act’s passage is that it raises a family’s awareness of the need to save for their loved one with a disability. Over the years, we have provided training sessions to families about planning for their family member with a disability. At the beginning of a workshop, we frequently ask if savings have been set aside for their typical child’s college education; almost all hands are raised. The next question we ask is if money has been set aside for their child with a disability; very few hands are raised.

One of the reasons for this deficit of saving is that in the past, many families felt that there would be adequate government programs in place for their child in the future. Now, families are beginning to realize that they must save on their own. Many entitlements end when children graduate from school, and the increasing demand for services has placed excessive financial pressure on the state agencies that have provided these services. The cycle of raising the awareness for families to save for their child with a disability is similar to the evolution witnessed with the advent of the IRA and 401(k) plans.

One issue planners continuously have to overcome is that families frequently get a false sense of security that they are all set once they complete their estate plan and that they do not need to plan further. It is important to plan for the most probable event, that at least one of the parents will make it to life expectancy. Therefore, parents have to plan for both their lifetime needs as well as the needs of their children. Recognition of the ABLE Act will bring greater awareness to the fact that significant planning is required beyond wills and trust.

Protecting Government Benefits

Turning age 18 is a planning pressure point for individuals with disabilities. Prior to age 18, a parent’s assets and income are deemed as belonging to the child with a disability. This generally results in a child not being eligible for the federal government benefits of Supplemental Security Income (SSI) and Medicaid prior to age 18. When an individual reaches age 18, a parent’s income and assets are not deemed as belonging to the child. Therefore, at age 18, if an individual meets the definition of disabled and does not have more than $2,000 in his or her name, he or she will be eligible for SSI and Medicaid.

SSI provides a monthly stipend, and Medicaid funds health benefits and various support benefits for individuals with disabilities. Planners will frequently face situations where an individual with a disability has greater than $2,000 in savings, securities, or government bonds in his or her name. If this is the case, the child will not be eligible for SSI or Medicaid. Assets in an Uniform Transfers to Minors Act (UTMA) account (some states refer to them as UGMA) will not be counted as an available resource under SSI until the account is considered available to that child under state law, which is usually at age 18 or 21, depending on the state. The ABLE Act will help address this issue.

ABLE Act Provisions

One goal of the ABLE Act is to enable an individual with a disability to save money specifically for his or her own benefit. The funds in an ABLE account can grow tax deferred and will come out tax free when used to pay for qualified expenses for the beneficiary. Examples of qualified expenses are transportation, assistive technology, health and wellness, housing, and employment support. Note that when distributing for non-qualified expenses, the pro-rata portion of the earnings attributable to the non-qualified expenses are subject to tax plus a 10 percent penalty.

Although the language in the ABLE Act specifically states that distributions are allowed for housing, a Social Security Bulletin dated December 5, 2014 states that distributions for housing will have an impact on SSI benefits (see www.ssa.gov/legislation/legis_bulletin_120514.html). Housing expenses are intended to receive the same treatment as housing costs paid by outside sources (SSI benefits subject to reduction of 1/3 federal SSI payment, as applicable). At this point, planners should be aware that clarification around distributions for housing expenses requires further attention from the Treasury.

An individual can only have one ABLE account, and the maximum annual contribution by all participating individuals is tied to the annual gift exclusion, $14,000 in 2015. To qualify, the individual’s disability has to occur before age 26. Assets up to $100,000 are excluded from income and asset tests. In addition, unlike 529 college savings plans where distributions are not monitored to make sure they are used for qualified expenses, distributions from ABLE accounts will be reported to Social Security each month.

The accounts will be administered by each state. The current plan is that each state will run the program similar to the 529 account. Because each state will have its own regulations, it is possible for states to allow special state tax benefits. Investment allocations within the account may be adjusted two times per year.

A significant consideration in using the ABLE account in planning occurs when the beneficiary dies with assets in the account. Essentially, Social Security will act as a creditor of each ABLE account. Monthly accounting sent to Social Security contains all of the distributions from the account. These will be recorded, and at the beneficiary’s death, the account will be reconciled, and Social Security will be reimbursed for any payments made on the beneficiary’s behalf. After Social Security is paid back, the remaining assets will be distributed from the account to the contingent beneficiaries. This Medicaid pay-back provision is a drawback of the ABLE account.

One difference between the ABLE account and the 529 college savings account is that in a 529 account the owner is the donor and the beneficiary is the college student. In an ABLE account, the owner will also be the beneficiary. The reason for this is many adults with disabilities will open ABLE accounts with their own resources and need the ability to control their own funds. However, there will have to be provisions when an individual is under a guardianship or power of attorney and is not competent to make financial decisions. This is one of the situations where the Treasury/IRS will issue guidance.

Planning Strategies for Using the ABLE Account

Although funds can grow tax free in an ABLE account, plan restrictions and provisions reduce its effectiveness as a planning tool. Despite this, there are a few instances where ABLE accounts are very appropriate.

The following are five situations in which an ABLE account should be considered as a planning option:

An ABLE account provides an individual with disabilities the opportunity to save money without being disqualified for SSI eligibility. Currently, when an individual is gainfully employed and able to save for themselves, they are at risk of losing their eligibility for SSI and Medicaid if they have more than $2,000 in their name.

A common issue arises when a family member with special needs reaches age 18 and has savings in their name over $2,000, disqualifying them from receiving government benefits. Many times, this is a result of an individual receiving birthday or holiday funds over the years that were then deposited into some type of savings account. Two options currently exist to remedy this situation. The first is to create a first-party special needs trust (a Medicaid-payback trust, also known as an OBRA 93 trust) and transfer the funds into the trust. This is suggested for larger sums of money, but not practical for smaller amounts because of the costs to draft this type of special needs trust and the potential costs for annual tax returns and accounting. The second option is to enact a “Medicaid spend down.” This involves purchasing various items that the individual may need with the goal of getting the balance below $2,000, and can often result in wasteful spending. A new option that should be considered is transferring the assets to an ABLE account, which can help avoid the wasteful spending and the costs of setting up the trust.

The same issues apply to assets in UTMAs or UMGAs as with assets in an individual’s name; assets over $2,000 must either be transferred to a special needs trust or spent down to avoid disqualifying an individual for government benefits. The assets in UTMAs or UGMAs are not countable until an individual turns either 18 or 21, depending on the state. The special needs trust will have to be a D4A trust (also known as a payback trust), because there will be a Medicaid payback. Current language states that you can transfer money from a UTMA or UGMA account into an ABLE account. Because the contribution to an ABLE account is required to be cash, any investment positions will have to be sold.

When an individual with a disability receives SSI benefits and is incapable of managing their SSI payments, a representative payee is appointed to open an account called a representative payee account. The individual’s SSI check is deposited into the “rep-payee” account, and the money is used to pay for the beneficiary’s day-to-day needs such as food and shelter. This account must stay below the $2,000 threshold. In cases where an individual lives at home with his or her parents and they begin to receive SSI, one planning strategy is the parent can use the SSI payment to pay for the individual’s room and board and then subsequently deposit the personal funds that they were using to cover these expenses into an ABLE account. The SSI funds are used to pay for expenses that the parents had been paying for prior to their child receiving SSI, therefore the family will be cash flow neutral.

Grandparents can fund an ABLE account for their grandchild. Frequently, grandparents fund 529 college plans; instead they can fund their grandchild’s ABLE account.

With each of these planning strategies, it is important to remember that an individual can only have one ABLE account.

Comparison of Savings Options

Although many have compared the special needs trust to an ABLE account, the comparison can be misleading because a special needs trust is an estate planning tool, while an ABLE account is a wealth accumulation vehicle. However, I will include this comparison because of the fact that it is being frequently discussed.

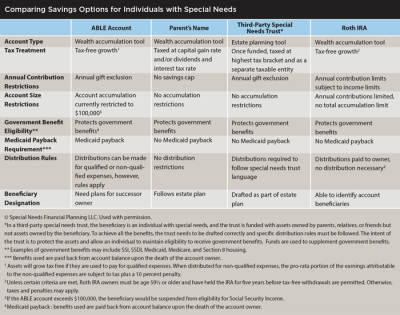

The previous chart compares four common savings options:

- ABLE account

- Parent’s save in their own name

- Third-party special needs trust

- Roth IRA

Overall, unless parents have more than adequate resources to provide for their own personal needs and have an estate that will result in significant estate taxes, it is advised for parents to consider saving money in their own name for their child. They may then provide for their child at the death of the second parent by funding a special needs trust.

Another attractive option to consider is to have parents fund Roth IRAs to provide funds to help plan for their child’s long-term supplemental needs. Roth IRAs provide tax benefits similar to those of the ABLE account, but is not an irrevocable gift nor are there restrictions on how the money may be used. An issue with the Roth is that a parent must be at least age 591/2 to take money out of it. Every family’s circumstance can be different, and it is the planner’s job in working with families to help them determine the most appropriate planning tools.

There has been a lot of excitement in the disability community regarding the passing of the ABLE Act. During the 10-year period required to get the bill passed, there has been a growing awareness about the need for families to save for their loved one with a disability.

Although there has been a lot of enthusiasm about the bill, it is important for planners to work with families and remind them that this is not the only solution for them. ABLE accounts have many positive features, however families should be aware of certain features before they begin to fund the accounts. Simply put, ABLE accounts may be a helpful planning tool, but because of the account’s limitations, they should not be the cornerstone of a family’s planning strategy.

John W. Nadworny, CFP®, is director of special needs financial planning at Shepherd Financial Partners and co-author of The Special Needs Planning Guide: How to Prepare for Every Stage of Your Child’s Life. He is a registered representative of, and securities and financial planning are offered through LPL Financial, member FINRA/SIPC. Special Needs Financial Planning and Shepherd Financial Partners are separate entities from LPL Financial.

The opinions voiced here are for general information only and not intended to provide specific advice or recommendations for any individual, nor intended as tax or legal advice. There is no assurance that the techniques and strategies discussed are suitable for all individuals or will yield positive outcomes. Investing involves risk including loss of principal. Prior to investing in an ABLE account, investors should consider whether the investor’s or designated beneficiary’s home state offers any state tax or other benefits available for investments in such state’s ABLE program. Consult with your tax adviser before investing.

Learn More

For more information on the differences between ABLE accounts and 529 plans, see the February 2015 Tax & Estate column “ABLE Accounts: An Option for Families with Disabled Children” by estate planning attorneys Randy Gardner and Leslie Daff.

Access previously published Journal articles in the archives (FPAJournal.org) or through the Journal app, available in the Apple App Store and Google Play.