Journal of Financial Planning: March 2011

James Grubman, Ph.D., of Family Wealth Consulting, is a psychologist and consultant to families of wealth and the advisers who serve them. His website is http://www.jamesgrubman.com/.

Kathleen Bollerud, Ed.D., is a psychologist and executive coach specializing in leadership development and succession planning. Her website is http://www.bollerud-holland.com/.

Cheryl R. Holland, CFP®, is a principal with Abacus Planning Group, a comprehensive, financial advisory firm serving families, www.abacusplanninggroup.com.

Executive Summary

- Severe overspending habits can be highly resistant to change because they share many characteristics of addictions.

- Prochaska’s Stages-of-Change Model has been used effectively in treating addictions and has been helpful in debt counseling. This article explains the Stages-of-Change Model using language easily accessible to financial advisers and their clients.

- Five stages of change are described in this paper: denial, ambivalence, preparation, action, and maintenance—along with the client’s potential slide into relapse.

- The article provides guidance for assessing the overspending client’s readiness to change and describes techniques for moving clients toward lasting success in controlling overspending habits.

The overspending client is one of the greatest challenges for financial planners. Poor budgeting, impulsive or addictive spending (regardless of affluence level), and the debt these habits can cause often result in a request for financial planning help. Even when a windfall is the catalyst for a client seeking advice, overspending must be dealt with if clients are to achieve their financial aspirations.

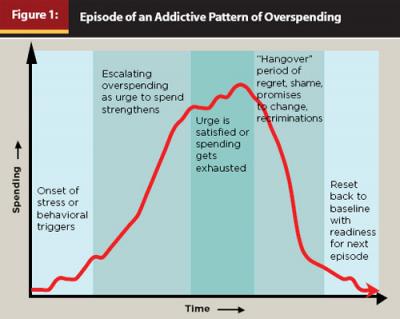

Episodes of severe overspending are very similar to patterns of many addictions.1 Emotional or behavioral stressors can trigger a spending cycle (see Figure 1), leading to escalation of spending until the urge is eventually satisfied or the money runs out. Shame often kicks in when the out-of-control behavior has passed. Defensiveness and/or remorse then arise as one deals with the damage done to bank accounts, credit card balances, and relationships, followed by repeated promises and short-term attempts to change. Addictive overspending eventually returns when the underlying emotional conditions reassert themselves. It is this pattern of emotional spending, combined with the presence of negative financial consequences, that defines the severe overspender.

Even seasoned advisers can feel powerless in the face of entrenched overspending. This helplessness is not due just to the addictive nature of the behavior but is also a result of advisers having little training in how to help clients change a difficult set of habits. Without a solid understanding of client psychology, you might believe the following inaccurate assumptions about behavior change:

- If the facts indicate someone needs to change, then the person should be ready and willing to change

- All clients who understand they have a problem are prepared to make a change for the better

- Being unable or unwilling to change represents resistance to you and the facts

- Once a change has been made it should be easily sustained

Most advisers take the rational, commonsense approach of showing financial projections designed to heighten clients’ awareness and lead to fiscal restraint. Though a factual approach can be persuasive, the key factor is not rationality but receptivity. When clients are simply not ready to hear about what will happen if they keep on overspending, your best warnings will fall on deaf ears.

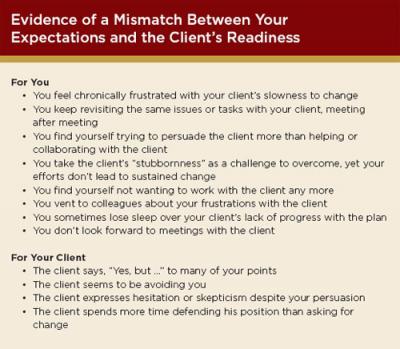

Another common approach is to use persuasion techniques grounded in sales and marketing. You might view the overspending client who is hesitant or in denial as a challenge to be conquered rather than as a person to be understood and helped. When reason and persuasion don’t succeed, the temptation is to blame the client for the failure of the financial plan. Lack of progress and the corrosive effects on the client-adviser relationship can lead you to either fire your client outright or allow the relationship to deteriorate to the point where he or she doesn’t return.

Several authors have described psychological issues that may underlie excessive spending.2 Though accurate, these approaches often lack practical, actionable recommendations beyond simply helping the client get past his or her emotional money issues. Change can be a process occurring in specific, predictable steps facilitated by the knowledgeable professional. Knowing how to accurately identify and assist the process of change enables you to tailor interventions to your client’s situation. This knowledge is critical to your success with overspending clients.

The Stages-of-Change Model

A groundbreaking model of how people change was first published by James Prochaska, Carlo DiClemente, and their colleagues in the late 1970s.3 Termed a “transtheoretical” model because of its agnostic stance on psychological theories of personality or treatment, the Stages-of-Change Model has been employed extensively for smoking cessation, weight loss, exercise, stress management, and substance abuse.4

In Prochaska and DiClemente’s model, the road to behavioral control essentially tracks the progression in the client’s readiness to change. It starts with denial (the person is unaware of the need for change) then moves through ambivalence (the person explores reasons for and against change) to preparation (the person prepares for and commits to change) and ultimately to action (the person actively engages in establishing new behaviors in place of the old). Upon successfully completing the first four stages, the person moves to maintenance in which he or she works to sustain the changes. The model also addresses the major challenge in sustaining change—the phenomenon of relapse. During relapse, the person may slip from current change efforts and return to an earlier stage. The universality of these stages in behavioral change is remarkable.

Experts in consumer credit counseling have used the Stages-of-Change Model with good success.5 The model addresses the ingredients for change at the client level and the adviser-relationship factors that influence change behaviors. The financial planning profession, however, remains largely unaware of the model despite its excellent utility. Even when advisers are aware of the model, the techniques for applying it have not been well documented.

Accurately Assessing a Client’s Stage of Change

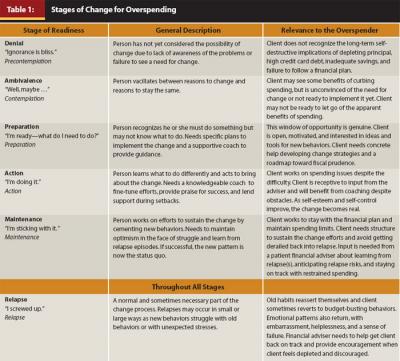

Table 1 describes the stages of readiness and how they appear with the overspending client. Prochaska’s term for each stage is presented in italics. We suggest using simpler terms for both clients and advisers to understand.

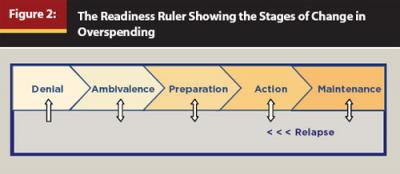

The stages of change in overspending may be conceptualized and measured along a type of Readiness Ruler6 (see Figure 2). In order to motivate clients to change overspending, you have to be able to identify where the client is in the change progression and intervene with techniques effective for that stage. Miller and Rollnick7 describe “motivational interviewing,” a method for eliciting a person’s intrinsic motivation to change. While their work focused on helping clients deal with addictions, its application for financial advisers is useful for understanding and helping the overspending client.

You can evaluate the client’s change-readiness through the use of guiding questions, careful listening, and close attention to the client’s behavior. When it comes to behavioral change, the client’s actions truly speak louder than words. Some useful questions to evaluate readiness include:

On a scale of 1–10, where 1 is “not at all” and 10 is “extremely”:

- How important is it for you to change your spending patterns? Where would you say that you are?

- How confident are you that, if you decided to change your spending habits, you could do it?

Clients will base their responses on their readiness to change. Deniers will likely answer with low numbers (1–3); clients who are ambivalent may respond mid-range (4–6); and clients who are prepared to act will respond with high numbers (7–10).

Ask clients to respond to the following questions:

- Do you think that you might change your spending in the next six months?

- Do you intend to do something about your spending in the very near future (next month)?

- Are you ready to take action now to deal with your spending?

- Have you made progress on your spending and then slipped?

- Have you resolved your spending problems more than six months ago?

Deniers will answer no to most or all of the inquiries. People who are ambivalent may answer yes to question 1 or 2, although they may be only partially convinced of the need to change. Preparation and action clients will answer yes to questions 2 and 3, and they may endorse question 4 if they’ve previously attempted some change on their own. A person in relapse will respond positively to question 4. A person in the maintenance stage will probably answer yes to question 5.

Approaching Clients in the Denial Stage

Overspending clients in the denial stage are either unaware of their problem with spending or unwilling to change it. They don’t acknowledge any need to change and can be quite defensive about it. A client who is deeply entrenched in denial will be impervious to logic or persuasion by advisers tempted to cajole them into “facing reality.” Arguing, criticizing, shaming, or blaming clients in denial will usually just worsen their resistance.

Any attempt to work with deniers requires building rapport, exploring discrepancies between the client’s personal aspirations and their spending behavior, and educating clients while remaining neutral and helpful. The main priority is to develop a solid working relationship. These clients need to feel understood, not judged, if they are to lessen their defensiveness. By encouraging clients to describe what is currently happening financially and how they would ideally want it to be, you can stimulate discussion about the need for change. Many deniers are not ready to listen to the implications of their overspending until they hear about it from someone who has a nonjudgmental manner. Only then can you educate them, provide benchmark information, and demonstrate the long-term financial impact of their current path. This stance is the only one to take with clients in denial if you want to lay the groundwork for possible change later on.

A strategy with clients in denial is to inquire, “It seems your spending is something that you really don’t want to change at this point. Is that the case?” With confirmation, you can comment, “It feels irresponsible for me not to point out your potential financial jeopardy. At the same time, I don’t want to ruin our relationship trying to convince you. How do you think I can be helpful to you?” The client’s response to this conversation will give you good information about whether the advisory engagement is even viable.

Deniers are often brought to a financial adviser by someone in their life who is not in denial but is suffering from the overspending loved one and actively wants that person to change. The partner may be much more motivated for the change than the client is. Working with the couple may be more helpful than with the overspending individual alone. Nonetheless, you need to build rapport with both partners as much as possible, maintaining a neutral and helpful posture to avoid the risk of undermining trust with the denier by obviously siding with the partner.

Ultimately, you need to evaluate whether to commit time and energy to working with a person entrenched in denial or to devote your resources with clients more responsive to change. If you accurately assess the potential client as not ready to change, it’s best to refuse the advisory engagement. Repeated, ineffective efforts to change a denier can be a drain not only on time and resources but also to your emotional level, leading to burnout. (See “Evidence of a Mismatch” sidebar.)

Working with the Ambivalent Client

Ambivalence may be the most challenging yet potentially the most rewarding stage for you to address. Ambivalent clients consider the possibility of change but are not ready to make a commitment to it. Compared to deniers who talk convincingly about the status quo with minimization of its downside, the ambivalent client will speak about both the pleasures and the perils of overspending.

Charts, graphs, and spreadsheets showing financial projections may be highly useful for clients in ambivalence because there is increasing receptivity to learning about the consequences of their behavior. However, the biggest danger in working with ambivalent clients is to assume they are wholly determined to solve their spending problem. Ambivalent clients may be barely out of denial, or they may be still a long way from jumping off the fence into preparation. The adviser who starts trying to move the client away from overspending habits too quickly will find this pressure backfires. The client will give many “Yes, but …” responses, coupled with reasons why these plans can’t work. At that point, you need to recalibrate and recognize that the client may need more support to move through ambivalence to preparation for action.

Your goal should be helping the client explore and resolve ambivalence rather than stay stuck in it. How you interact with the client can substantially influence the direction in which he or she resolves this ambivalence.8 If you are overly persuasive or confrontational, the resistance will go up. If you are supportive and open, the resistance will go down. The client will talk more about the need for change.

Ambivalent clients need to have someone acknowledge both sides of the argument in their head and their heart. You can build rapport by comments such as: “It seems part of you recognizes spending is an issue and part of you isn’t ready to deal with it yet—is that what you are feeling?” If this statement rings true with the client, ask about the benefits of spending the way they do. It’s counter-intuitive, but starting with an examination of the benefits of “no change” will often lead to the client’s exploration of the problems of the status quo and the advantages of change. Also, questions such as, “What concerns you most about your current or future financial situation?” can draw out the “change” side of the client’s ambivalence. You can then gently reflect back upon the pros and cons in a neutral way. This review allows the client to hear his or her own reasoning in all its complexity, potentially increasing motivation to resolve things.

Keep in mind that ambivalent clients often cannot envision what would have to be done to conquer the overspending. They may over- or under-estimate the difficulty of changing. Encouraging a discussion of potential action steps for the client without persuasion may allow the ambivalent client to develop optimism that change is possible. What ambivalent clients need is both support and information offered in a low-key manner.

When the Client Is in the Preparation Stage

Preparation is the stage when clients make a preliminary decision to change their overspending habits. At this point, clients may start to do more reading about better financial habits on their own, they will take your financial projections to heart, they notice the downsides of overspending by others, and they experience their own disasters more clearly and painfully. They are coming off the fence onto the side of change. A client will signal this shift through decreased resistance to change, increased talk about the disadvantages of the status quo, more frequent statements about their intent to change, more active requests for how to manage their money responsibly, and more careful follow up on any homework requests. The client is prepared to start making the change.

Recognizing this window of opportunity to facilitate new behaviors is crucial. The key at this point is to be neither too pushy nor too vague in developing a plan. Enhance the client’s commitment to change and to think through action steps by first soliciting suggestions from the client about how he or she might change the overspending. Offer questions such as:

- It sounds like you don’t think you can continue to spend this way—what do you think you could do differently?

- What changes, if any, are you thinking about making?

- What works for you when you do budget and spend carefully? How have you succeeded in the past?

- What do you see as your options or next steps?

Because people are often most receptive to their own ideas, eliciting self-advice from the client can be highly motivating. Phrase these questions tentatively, discussing what the client “might consider” rather than pushing for commitments. Then, after the client requests it or you respectfully ask the client’s permission, you can offer advice based on professional experience and expertise. Give advice in a way that acknowledges the client’s ultimate control and decision-making. In addition, the client will often need help thinking through the obstacles to their new behaviors and how to deal with them.

Your role is as a supporter, guide, and mentor. The outcome of the preparation phase should be a concrete plan of action with clear goals and feasible strategies for change.

The Client Moves into Action

The action stage is the one most advisers love, because change is clearly happening and problem-solving strategies come to the forefront with a motivated client. You should explicitly ask how to be helpful as the client works on the new spending behaviors, becoming a partner and collaborator working with the client to achieve their goals. As the client implements the plan, it can be helpful to periodically summarize the client’s financial goals and the steps to achieve these goals.

As clients take financial actions such as cutting up credit cards and saving more, they will also be learning new emotional behaviors such as allowing spending urges to pass and finding new ways to manage stress. They need to learn how to handle those emotional triggers that would normally initiate an episode of overspending. Clients need frequent check-ins about how they are doing, both financially and emotionally. During these sessions, you provide confirmation and support to clients that they are on the right path to achieve their goals. You can watch for any renewed ambivalence and deepen the client’s commitment to action by questions such as, “Is this what you want to do?” Some clients will benefit from writing out their plan or making a public commitment by sharing their decision with important people in their lives. You should also acknowledge how difficult the effort may be and offer praise and encouragement. Meanwhile, you and the client monitor the plan and work together to adjust parts that may need to be revised.

Managing Relapse

The Stages-of-Change Model recognizes relapse as a normal and sometimes necessary part of the change process. It is a rare person who does not slip and regress to an earlier stage. What is important is that relapses not be viewed as failure but as normal stumbling blocks on the path to success. Just as mistakes are part of learning any new behavior, relapses reveal much-needed information about what was not adequately anticipated, what skills need special attention, and what risks are most likely to derail this individual client.

Relapse must be carefully assessed. You can ask:

- How long and how hard did you work to improve before the relapse? What successes had you achieved?

- Are you slipping because you don’t have the skills yet, or because you have the skills but didn’t use them? Do you need new skills, or more strategizing about how to stay on track?

- Did you run into a situation that you were unprepared for and need to learn from?

- Were you gradually backsliding before this occurred? In what ways?

- What have you learned from this relapse that can be helpful in the future?

As the adviser, your efforts should focus on helping the client get back to action rather than falling into preparation, ambivalence, or (worst of all) denial. Relapsing clients need help to avoid excessive discouragement and to recommit to their financial goals. You too may need to keep these principles in mind and not become too discouraged or frustrated. By normalizing the relapse experience and focusing on learning from it, both you and your client can keep on track.

The Ultimate Goal: Maintenance

Even when the client has taken effective action to control overspending, the path forward may be neither smooth nor straight. Clients will often miss their old lifestyle and feel a pull toward old spending behaviors. During the maintenance stage, clients need to consolidate the gains they have made, building in routines and methods to help sustain their new lifestyle. They may also have to develop techniques to deal with old cues or new triggers for spending.

You should continue to be engaged at this stage on a tapered schedule of meetings. You will be more helpful than you think in reinforcing the client’s efforts, praising success toward spending or saving milestones, and pointing out benefits of the newfound financial independence. A hidden benefit is that you will be able to catch early signs of relapse and step in with support and education about the risks of relapse.

Tips for Using the Stages-of-Change Model with Clients

From our experience, financial planners can expect reasonable progress using this model with an individual client within approximately 12 to 24 months of beginning the process. Several tips may be useful to keep the process moving. Teaching the stages of change to the client at the start can help build understanding and acceptance of the client’s experience. Along the way, periodically assessing and discussing where the client is in the cycle can keep momentum going and motivate the client toward the next effort. Clients do not always fit neatly into one stage, or they can seem to cycle through stages within a several-month time span. You can sort through any confusion by going back over the model with the client to get his or her sense of what is happening.

Many clients who are attempting to leave addictive spending behind will disclose emotional issues you may feel uncomfortable handling at times. They may talk about family stresses, an enabling spouse or parent, deep unhappiness they “medicate” by overspending, or fears of losing status or relationships based solely on materialism. The best approach is to involve a mental health therapist (not instead of your services but in collaboration with your services)9, addressing the client’s emotional issues while still pursuing good financial strategies. For clients entrenched in denial, willingness to work with a therapist is a favorable signal that you might work with them effectively later on.

Some indicators that a therapy referral may be needed include:

- The client discloses significant past or present family issues painful enough to halt progress during your meetings

- The client admits to other ongoing addictive behaviors (substance abuse, gambling, sex addiction) that go well beyond the overspending

- The fighting between spouses or partners is so uncomfortable that you feel overwhelmed, or you are worried about one or both partners’ safety

- The client shows signs of anxiety or depression that seem severe enough to require a professional’s expertise

If you are unsure whether to involve a therapist, contact one to discuss the situation with him or her for some guidance and support.

A Client Example: Anna’s Case

Anna Jenkins’s career as a nurse anesthetist provides her with excellent income and flexibility for raising her two daughters. When her husband died five years ago, Anna received $450,000 in life insurance proceeds plus his retirement plan. Anna spent freely on special trips, renovation projects for her home, and cars for herself and her daughters. As a result, she has not only depleted the insurance proceeds but has even remortgaged her home. Now with a $640,000 inheritance soon to arrive from her father’s passing, Anna’s brother refers her to Sharon Anderson, his financial adviser, in hopes of finally stopping her overspending.

Anna shares her financial history with Sharon and articulates her goals: educate her daughters, travel, and retire in her 60s. Recognizing the need to be tactful about Anna’s financial behaviors, Sharon begins with, “What do you enjoy about your lifestyle and spending?” Anna confides that she uses money to make herself happy by having “best dressed” daughters, staying in nice accommodations, and selecting “the perfect curtains.” When Sharon asks, “Do you have any concerns about spending?” Anna shares her worries about being a poor role model for her daughters and retiring without enough savings. She admits she often feels ashamed walking by the piano she bought that no one plays.

Before Sharon agrees to work with Anna as a client, she gauges Anna’s willingness to work on her overspending. Sharon asks Anna, “On a scale of 1–10, how important is it for you to change your spending patterns in order to achieve your goals?” After a moment, Anna replies, “I’m probably at a 6.” Sharon briefly describes the stages of change to Anna and reviews the Readiness Ruler with her (Figure 2). Sharon proposes that Anna might be in the ambivalence phase: “You love nice things and enjoy trips with the girls, but you acknowledge you have no retirement, the cushion of the life insurance proceeds is gone, and you’re likely to repeat your mistakes with your upcoming inheritance.” Sharon avoids making judgmental statements or confronting Anna with facts, projections, and arguments. Understanding Anna’s place on the Readiness Ruler helps Sharon manage her own frustrations and plan realistically with her client. This approach allows Anna to think about her ambivalence; she becomes open to hearing about how she might address her overspending. They decide to meet again in a month to see where Anna is with regard to her spending. Sharon offers to review Anna’s current financial status and her projected needs to understand Anna’s financial picture.

After several meetings, the light bulb goes on for Anna. She is amazed when she recognizes the disparity between her reality and her goals. She admits, “I better get to work!” Anna is now in the preparation stage, wanting to change but at a loss for how to go about it. Sharon and Anna discuss “need to haves” compared to “nice to haves.” When Sharon shows the graph of how an overspending episode mirrors an addiction process, Anna breaks into tears and says, “I never realized others went through the same thing.” Sharon suggests they initially meet monthly to create a budget and work together on changing Anna’s spending habits. Anna agrees to the advisory engagement, understanding the full change process will take significant effort.

Anna moves into the action phase and begins to develop new and appropriate spending habits. Sharon celebrates Anna’s successes, reinforcing Anna’s desire to succeed. When Anna experiences setbacks such as a lavish Sweet 16 birthday party for her daughter, Sharon puts this stumble into perspective by reviewing the phenomenon of relapse. By two years from the first meeting, Anna is staying within her spending limits, contributing to her 401(k), and managing her father’s inheritance prudently in a long-term investment account. Anna and Sharon meet less frequently in the third year but keep the spending and budget issues front and center. Not only does Anna take pride in her new approach to managing money, she takes on a new role with her own daughters—teaching them how to be financially responsible adults themselves.

Summary and Conclusion

Accurate assessment of a client’s readiness for change leads to useful techniques and expectations as the client struggles to undo dysfunctional spending habits. With this knowledge, you can shift from frustrated helplessness to skillful effectiveness with some of your most vexing clients. The payoffs are many:

- Recognition for both you and the client that the earliest stages of change can be part of a potentially fruitful process rather than a permanent condition of hopelessness

- Better recognition of which clients are ready and likely to change, and which clients are not

- Better allocation of resources to those clients most able to profit from the financial planning process

- Better client relationships with fewer push-pull power struggles

- Better client satisfaction because of the perception you are understanding, empathetic, and helpful rather than irritated, frustrated, or condescending

- Greater effectiveness helping clients move along the change spectrum

Financial professionals who embrace the Stages-of-Change Model may find not only new techniques for helping clients but new energy to approach the difficult area of client overspending.

Endnotes

- Glatt, M.M., and C.C.H. Cook. 1987. “Pathological Spending as a Form of Psychological Dependence.” Addiction 82, 11: 1257–1258; Mellan, O. 2009. Overcoming Overspending: A Winning Plan for Spenders and Their Partners. 3rd ed. Money Harmony Books.

- Carrier, L., and D. Maurice. 1998. “Beneath the Surface: the Psychological Side of Spending Behaviors.” Journal of Financial Planning (February); Mellan, O. 2009. “Understanding Overspending: Tell Me that You Want the Kind of Things that Money Just Can’t Buy.” Investment Advisor (January): 58–59; O’Neill, B. 2005. “Motivating Clients to Develop Constructive Financial Behaviors: Strategies for Financial Planners.” Journal of Financial Planning (January).\

- Prochaska, J.O., and C.C. DiClemente. 1983. “Stages and Processes of Self-Change of Smoking: Toward an Integrative Model of Change.” Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 51: 390–395.

- Fava, J.L., W.F. Velicer, and J.O. Prochaska. 1995. “Applying the Transtheoretical Model to a Representative Sample of Smokers.” Addictive Behaviors 20: 189–203; Prochaska, J.O., C.C. DiClemente, and J.C. Norcross. 1992. “In Search of How People Change: Applications to Addictive Behavior.” American Psychologist 47: 1102–1114; Gerard, J.C., D.M. Donovan, and C.C. DiClemente. 2001. Substance Abuse Treatment and the Stages of Change: Selecting and Planning Interventions. Guilford Press; DiClemente, C.C. 2006. Addiction and Change: How Addictions Develop and Addictive People Recover. New York: Guilford Press; Prochaska, J.O., and J. Norcross. 2007. Systems of Psychotherapy: A Transtheoretical Analysis. Belmont, California: Thomson; van Wormer, Katherine. 2008. “Counseling Family Members of Addicts and Alcoholics: The Stages-of-Change Model.” Journal of Family Social Work 11, 2.

- Kerkmann, B.C. 1998. “Motivation and Stages of Change in Financial Counseling: An Application of a Transtheoretical Model from Counseling Psychology.” Financial Counseling and Planning 9, 1: 13–20; Xiao, J.J., B. O’Neill, J.M. Prochaska, C. Kerbel, P. Brennan, and B. Bristow. 2001. “Application of the Transtheoretical Model of Change to Financial Behavior.” Consumer Interests Annual 47: 1–9; Xiao, J.J., B. Newman, J.M. Prochaska, R. Leon, and R. Bassett. 2004. “Voices of Debt Troubled Consumers: A Theory-Based Qualitative Inquiry.” Journal of Personal Finance 3, 2: 56–74; Xiao, J.J., B.M. Newman, J.M. Prochaska, B. Leon, R.L. Bassett, and J. Johnson. 2004. “Applying the Transtheoretical Model of Change to Consumer Debt Behavior.” Financial Counseling and Planning Education 15: 77–88.

- The term Readiness Ruler has been used in the addiction literature to denote assessment of poly-drug abuse; see Hesse, M. 2006. “The Readiness Ruler as a Measure of Readiness to Change Poly-Drug Use in Drug Abusers.” Harm Reduction Journal 3, 3. We use the term here in this context differently as a way to understand readiness for change in general.

- Miller, W.R., and S. Rollnick. 2002. Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People for Change. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford.

- Miller and Rollnick. 2002.

- For an excellent review of issues and methods in utilizing therapists as part of the financial planning process, see Maton, C.C., M. Maton, and W.M. Martin. 2010. “Collaborating with a Financial Therapist: The Why, Who, What, and How.” Journal of Financial Planning (February): 62–70.