Journal of Financial Planning: June 2021

Executive Summary:

- As organizations move from defined benefit plans to defined contribution plans, it is becoming ever more important for individuals to take personal responsibility to financially prepare for retirement during their working years.

- Utilizing the 2018 National Financial Capability Study, analysis highlighted that higher incomes were associated with retirement preparation. This relationship was partially mediated by financial self-efficacy. The positive association between income and retirement preparation was partially explained by financial self-efficacy.

- Results suggest that the relationship between confidence in achieving a financial goal and retirement preparation is negative and significant. The more confident respondents appear to be about their ability to accomplish a financial goal, the less likely they are to be actively contributing to a retirement account.

- These results can guide financial advisers to target individuals who might stick to a retirement plan and encourage these working investors to actively contribute to their retirement plans.

- Financial advisers can also guard their clients against becoming overconfident in their ability to achieve financial goals as this may be a deterrent to contributing to a retirement plan.

Tim Sturr, CFP®, leads financial planning at Wells Fargo Advisors, holds a master’s degree in management from the Stanford Graduate School of Business, and is currently pursuing a Ph.D. in personal financial planning at Kansas State University. Sturr has research interests in financial psychology, prosocial behavior, and retirement preparation.

Christina Lynn CFP®, CDFA®, AFC®, a fee-only financial planner at Kahler Financial Group, holds a master’s degree in family financial planning from South Dakota State University and is currently pursuing a Ph.D. in personal financial planning at Kansas State University. Lynn has research interests in behavioral finance, positive psychology in financial planning, and divorce finances.

Derek R. Lawson, Ph.D., CFP®, is an assistant professor in the Department of Personal Financial Planning at Kansas State University, with research interests in behavioral finance, financial therapy, financial psychology, and relationship dynamics among couples. Lawson is also a financial planner at Priority Financial Partners based out of Durango, Colo.

JOIN THE DISCUSSION: Discuss this article with fellow FPA Members through FPA's Knowledge Circles.

FEEDBACK: If you have any questions or comments on this article, please contact the editor HERE.

NOTE: Click on the images below for PDF versions.

We live in an era where retirement preparation falls heavily on the shoulders of individuals. Whereas retirement preparation was once covered by employers (defined benefit plans), individuals are now primarily responsible for managing and funding their own retirement plans. Increasing healthcare costs and problematic forecasting of Social Security benefits magnify the need for financial preparation. While it is critical that individuals adequately prepare for retirement, all households are not doing so. This puts their financial security at risk in retirement (Kim et al. 2014; Kim and Hanna 2015). According to a 2019 Federal Reserve study, 25 percent of Americans have no retirement savings and 64 percent of pre-retirees do not feel they are saving enough (Federal Reserve System 2019). Unfortunately, most households also do not understand the implications of being underprepared for retirement (Kim and Hanna 2015). This study contributes to the existing body of knowledge by identifying a mediating effect of financial self-efficacy on the relationship between income and retirement preparation. It also establishes a new operationalized construct to measure financial self-efficacy and differentiates this from confidence to achieve a financial goal.

Literature Review

How does one prepare for retirement? Pfau (2011) posited that saving during the accumulation phase of life is key to retirement planning and saving early and consistently for retirement is an ideal way to prepare for retirement. Unfortunately, most Americans feel they are neither saving enough, nor have the ability to save more (Martin Jr. and Finke 2014). Blanchett, Finke, and Pfau (2017) exposed the need for households to significantly increase savings rates to maintain the same standard of living in retirement. Previous research has used various measures of retirement preparation, including: (a) retirement plan eligibility; (b) active retirement plan contributions; (c) perceived adequacy of expected retirement income (Lee, Hassan, and Lawrence 2018); and (d) income replacement ratio of projected future retirement savings (Kim, Lee, and Hong 2016). Key factors positively associated with retirement preparation are income and excellent health (Lee et al. 2018). Self-efficacy theory provides a theoretical framework for analyzing the relationship between retirement preparation and financial-self-efficacy.

Self-Efficacy Theory

Self-efficacy is the belief in one’s capability to successfully handle a given situation (Bandura 1977). It is reflected by how well an individual expects to execute a plan of action in a prospective situation. Bandura (1977) identified four main sources of influence regarding self-efficacy: mastery experiences, vicarious experiences, social persuasion, and emotional and physiological states.

Financial Self-Efficacy

Self-efficacy viewed through the lens of personal finances is referred to as financial self-efficacy (FSE). FSE is defined as the belief in one’s own abilities to accomplish a financial goal or task, such as saving for a comfortable retirement. Personal financial management requires a sense of self-assuredness and is therefore related to FSE (Farrell, Fry, and Risse 2016). Asebedo and Seay (2018) found that when analyzing FSE, income was a significant predictor of saving behavior in older U.S. pre-retirees.

The four contributing factors of self-efficacy, as identified by Bandura (1977), can also apply to FSE. The most influential source is mastery experiences, which is the result of one’s previous experiences. Mastery experiences in FSE may be reflected by the financial experiences that an individual endures. Experiences produce performance outcomes that shape the nature of one’s self-measured capability. For example, the experience of buying a first home would be considered a mastery experience within FSE. Comparing houses, selecting a realtor, applying for a mortgage, deciding on the mortgage structure, coming up with a down payment, and adjusting to new monthly house-related expenses imprint on the individual and provide a reference point from which to learn for future decisions. If the homebuying process was a positive experience, it may generate a sense of accomplishment and serve to assure the individual that they can successfully handle similar future financial decisions.

Vicarious experiences, as they pertain to FSE, are when an individual witnesses how others handle financial situations. An example of this would be observing a sibling make important financial decisions and then witnessing the associated repercussions. For example, an individual may witness a sibling overspend and overborrow, and as a result, see them humiliated with having to borrow money from a parent. This negative vicarious experience may lower one’s FSE by causing self-doubt in their ability to do any better than their sibling.

Social persuasion, as applied to FSE, is the feedback received regarding financial matters. For example, positive social persuasion occurs when a financial adviser congratulates a client on strong savings habits. The client may feel proud of the recognition of a job well done. Negative social persuasion occurs when a banker notifies a client about a delinquent loan account and explains the implications of being late on loan payments. The client may feel ashamed of their inability to properly handle the loan. Positive financial social persuasion may build one’s FSE, where negative financial social persuasion may deteriorate one’s FSE.

In the context of FSE, emotional and physiological states can be a direct result of financial matters. For example, a single mother who runs out of money before the end of the month and can’t afford groceries or fuel for her car will likely feel stress or financial dissatisfaction. The harmful effects of stress cause individuals to doubt their capability to handle the financial situation, which is the cause of the financial dissatisfaction. Past research has tied financial satisfaction to FSE (Xiao, Chen, and Chen 2014). Financial satisfaction may be considered a proxy for emotional and physiological states when measuring FSE. Financial stress captures the negative emotional state (Asebedo and Seay 2018), whereas financial satisfaction captures the positive emotional state.

Financial Self-Efficacy and Savings Behavior

Empirical research links FSE to savings behavior, suggesting a possible positive correlation between FSE and retirement preparation. Asebedo et al. (2019) found that FSE had a direct and positive relationship with savings behavior among older adults. Farrell, Fry, and Risse (2016) examined the role of FSE in retirement saving strategies and found that among women, higher FSE is associated with investment and savings products while lower FSE is associated with the use of debt products. A greater sense of financial control, a component of FSE, predicted both saving intention and self-reported saving behavior within a sample of U.S. first-year undergraduate college students (Shim, Serido, and Tang 2012). Chatterjee, Finke, and Harness (2011) concluded that self-efficacy is a predictor of investments in financial assets and wealth creation. Savings behavior is a key determinant of retirement preparation. Therefore, if FSE is positively associated with savings behavior, FSE may also be positively associated with retirement preparation.

Hypotheses are drawn on past research and a theoretical framework that suggests a positive relationship between income and retirement preparation, and between FSE and savings behavior. This study proposes the following two hypotheses:

H1: Financial self-efficacy will mediate the relationship between income and retirement preparation.

H2: Confidence to achieve a financial goal will mediate the relationship between income and retirement preparation.

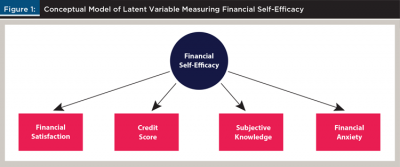

Figure 1 presents the conceptual model.

Methodology

Sample. The data came from the National Financial Capability Study (NFCS) that was conducted by ARC Research and was funded by the FINRA Investor Education Foundation. The NFCS is a multi-year study of Americans’ financial capability that began in 2009 and has been conducted every three years since. Data from the 2018 sample, which included over 27,000 households in the United States, was utilized. Leveraging non-probability quota sampling, the NFCS ensures variation in the sample. Interviews were conducted between June 2018 and October 2018. With at least 500 respondents from each state, the NFCS cross-sectional data reflects the broad adult population of the United States as represented by the U.S. Census Bureau American Community Survey.

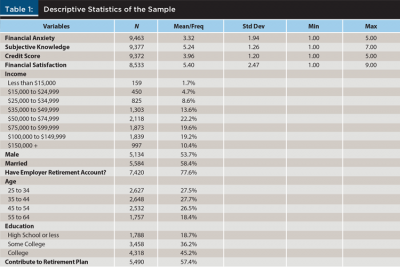

Given this study’s focus on retirement preparation, the sample was limited to households deemed most likely be currently engaged in preparing for retirement. As done in previous research, only full-time workers were included (Kim and Hanna 2015). The age limitation of 25 to 64 was imposed to capture the typical years that adults would be actively preparing for retirement, which is in line with previous research (Lee, Hassan, and Lawrence 2018). After applying these sample constraints, the final sample contained 9,564 subjects. Upon limiting the sample by age and working status, the majority of the sample was male (53.7 percent), married (58.4 percent), and had access to an employer-sponsored retirement account (77.6 percent). Over a third of the sample (36.2 percent) had some college, and even more had a college degree or higher (45.2 percent). Representing the largest of the income categories, 29.7 percent of the sample earned over $100,000 annually, while 19.6 percent earned $75,000 to $100,000, 22.2 percent earned $50,000 to $75,000, and 28.6 percent earned less than $50,000.

Measures

Retirement Preparation. Retirement preparation was an endogenous variable. It was a dichotomous manifest variable, answered by the survey question: “Do you or your spouse regularly contribute to a retirement account like a Thrift Savings Plan (TSP), 401(k), or IRA?” Pfau (2011) explained that savings behavior is key to achieving retirement income longevity. This survey question was believed to capture the active savings behavior of households, which was used as a proxy for retirement preparation. Those who responded as “don’t know” or “prefer not to say” were coded as not preparing for retirement. Several categorical demographic variables were controlled for in the model, including age and education. Gender was also controlled for as past research found gender to be a significant factor in retirement preparation (Glass and Kilpatrick 1998; Noone, Alpass, and Stephens 2010). Asebedo and Seay (2018) found that marital status was a significant predictor of saving behavior for pre-retirees. For this reason, marital status was included in the model as a control variable on retirement preparation. Access to an employer-sponsored retirement plan was controlled for because it is the primary vehicle for tax-advantaged retirement wealth accumulation for workers (Rhee 2013).

Income. Income was an exogenous manifest variable measured directly in the survey. Respondents were required to answer this question to continue with the survey, so there was no missing income data. The data for responses was ordinal in the data set with categories ranging from one (less than $15,000) to eight ($150,000 or more). There were six additional income categories in between, and they were uneven in width.1

Financial Self-Efficacy

The 2018 NFCS did not include the majority of survey questions required for the FSE scale created by Lown (2011). Alternatively, we measured FSE as a latent variable by incorporating the individual components of self-efficacy identified by Bandura (1977) as they apply to the realm of personal finances. Figure 1 represents a conceptual picture of this construct.

Mastery experiences were represented in the model by subjective knowledge, where one’s perceived knowledge is seen as a reflection of their skills or ability, suggesting they have performed, mastered, or achieved success in the past. Mastery experiences were also represented in the latent variable by financial satisfaction. Being extremely satisfied with one’s financial condition implies a perception of mastery of personal financial management. Financial satisfaction was measured by the survey question, “Overall, thinking of your assets, debts and savings, how satisfied are you with your current personal financial condition?” It was measured on a 10-point Likert-type scale, where 1 represents “not at all satisfied” and 10 represents “extremely satisfied.”

Social persuasion was represented in the model by perceived credit score, where feedback from credit bureaus can influence one’s sense of financial capability. Self-efficacy is influenced by encouragement or discouragement, thereby influencing an individual’s performance (Bandura 1977). It can be argued that a good credit score is a source of encouragement and a poor credit score is a source of discouragement. This manifest variable was measured by the survey question, “How would you rate your current credit record?” Five categorical responses ranged from “very bad” to “very good.”

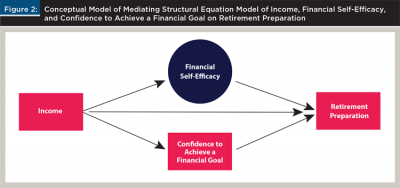

Emotional and physiological states were represented in the model by financial anxiety, which was supported by work from Grable, Heo, and Rabbani (2015) that connected financial anxiety and physiological arousal. The manifest variable of financial anxiety was measured by the survey question, “Thinking about my personal finances can make me feel anxious.” This question allowed respondents to answer on a Likert-type scale, with 1 representing “strongly disagree” and 7 representing “strongly agree.” The responses were reverse coded in the confirmatory factor analysis model to align directionally with the three other indicators of FSE. Vicarious experience was tested through parent’s education, and it did not have an appropriate loading factor in the confirmatory factor analysis model. As there were no other suitable proxies, vicarious experience was removed from the analysis. Figure 2 depicts the conceptual model for financial self-efficacy.

Confidence to Achieve a Financial Goal

An alternative measure of FSE was also analyzed, which we refer to as confidence to achieve a financial goal (CTAFG). It was measured directly by an NFCS survey question, which asks the respondent, “If you were to set a financial goal for yourself today, how confident are you in your ability to achieve it?” The categorical choices were: “not confident at all”; “not very confident”; “somewhat confident”; “very confident”; “don’t know”; and “prefer not to say.” This question was an alternative measure to the latent variable presented here for FSE. Similar to how authors handled the ordinal income data, CTAFG was treated as a continuous variable since it was a mediating predictor variable.

Analysis

Results of the study were achieved in multiple steps. In step one, descriptive statistics of all variables were generated to better understand the measurements. In step two, bivariate correlations were run on the four manifest variables within the latent FSE construct to analyze the relationship between the indicators. Third, a measurement model in confirmatory factor analysis was performed to test the factor loadings and model fit of the FSE latent variable. In step four, a correlation analysis was conducted on the latent FSE variable and the CTAFG manifest variable to identify the statistical relationship between the two. Finally, a structural equation model was employed to test the effects of FSE on income and retirement preparation.

Bootstrapping was used to test indirect effects from income to FSE to retirement preparation. Bootstrapping is a nonparametric resampling procedure and is the recommended approach to test mediation above the “Four-Step Approach” and “Sobel Test” (Briggs 2006; Preacher and Hayes 2004; Shrout and Bolger 2002). To adjust for standard errors, results were bootstrapped with 2,000 iterations, which were then interpreted based on a 95 percent confidence interval. In a parallel analysis, the authors ran a mediating structural equation model to test the effect of CTAFG on income and retirement preparation. Bootstrapping was also used in this step of the model.

Results

Descriptive Results. Descriptive statistics for core variables in the model are outlined in Table 1. Financial anxiety responses were positively skewed on the 1 to 7 Likert-type scale (M = 3.32, SD = 1.94). Respondents’ self-perception of their financial knowledge was left-skewed in the 7-point Likert-type scale (M = 5.24, SD = 1.26). On a scale of 1 to 5, individuals’ beliefs as to the quality of their credit scores were also tilted toward the higher end (M = 3.96, SD = 1.20). Lastly, respondents’ satisfaction with their current personal financial condition was centrally clustered (M = 5.40, SD = 2.47) on a 1 to 9 Likert-type scale. Note that due to respondents answering either “don’t know” or “prefer not to say,” sample sizes varied for each question, with all 9,564 respondents answering the income question since answering that question was a requirement to complete the survey. As it relates to the dependent variable, retirement preparation, 57.4 percent of the population was actively contributing to a retirement plan while 42.6 percent was not.

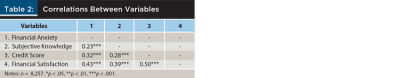

Bivariate Correlations. Pearson correlation statistics were run on all the manifest variables that are included in the latent construct of FSE. Listwise deletion was utilized on all “don’t know” and “prefer not to say” responses, leaving a sample size of 8,257. As highlighted in Table 2, all variables were positively correlated with p-values < .001 and Pearson correlations ranging from .23 to .50.

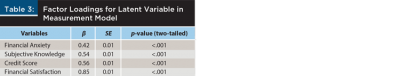

Measurement Model. A latent variable, FSE, was created utilizing the factors of financial anxiety, subjective knowledge, credit score, and financial satisfaction. These proxy measures aligned with the theoretical construct of self-efficacy. All factor loadings exceeded .40 and were acceptable levels for the latent construct (Kline 2016). See Table 3 for the loading factors. The model fit statistics suggested that the model fit the data well (Kline 2016). c2 (2) = 124.19, p > .05, CFI = .98, RMSEA = .08, SRMR = .02. The Cronbach’s alpha was .69. As the indicators and model fit statistics were deemed acceptable, the study continued with a full structural model.

Structural Model

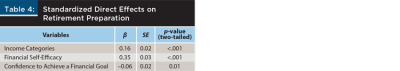

Non-Mediation Model. A full structural equation model was conducted to determine the association of income and retirement preparation, defined as the respondent actively contributing to a retirement account. Due to the ordinal nature of the income categories in the NFCS data set, the independent variable was treated as continuous. The latent variable construct of FSE, as well as the appearing related single NFCS question that asked participants how confident they were that they could achieve a financial goal (CTAFG) if they were to set one for themselves, were also analyzed. Note that responses to this question concentrated to the higher end with 2.9 percent responding either “prefer not to say” or “don’t know”; 3.9 percent responding “not at all confident”; 13.8 percent responding “not very confident”; 45.6 percent responding “somewhat confident”; and 33.7 percent responding “very confident.” Full information maximum likelihood was utilized to address missing data for respondents who answered, “don’t know” or “prefer not to say.” A correlation analysis was run on FSE and CTAFG to determine their relationship and found that they had a standardized correlation of .70 with a two-tailed p value < .001. Standardized results of the structural model are outlined in Table 4. Income was regressed on FSE and the CTAFG question, with similar control variables.

Overall model fit was appropriate (Kline 2016) with c2 (33) = 860.93, p < .05, CFI = .93, RMSEA = .05, SRMR = .07. A significant p-value for chi-square can be discounted when the sample size exceeds 400 (Kenny 2015). The model predicted 56 percent of the variance in retirement preparation (R2 = .56), 31 percent of the variance in FSE (R2 = .31), and 11 percent of the variance in CTAFG (R2 = .11). Income and FSE were positively associated with retirement preparation with significance levels < .001. A surprising finding was that CTAFG was negatively associated with retirement preparation with a significance level of p < .05. This was notable given the correlation of the FSE variable with the CTAFG variable mentioned previously.

Mediation Models

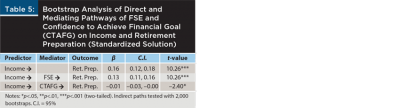

Both FSE and CTAFG were tested to see whether they would mediate the relationship between income and retirement preparation. FSE partially mediated the relationship between income and retirement preparation with a p-value < .001. The unstandardized coefficient went from 0.13 (p < .001) for income when tested on retirement preparation to 0.11 (p < .001) for income regressed on retirement preparation via FSE. CTAFG also partially mediated the relationship between income and retirement preparation with a p-value < .05. The coefficient went from 0.13 (p < .001) for income when regressed on retirement preparation to –.01 (p = .01) for income regressed on retirement preparation through CTAFG.

Bootstrapping procedures were used to examine: (a) mediating effects of FSE on income and retirement preparation; and (b) mediating effects of CTAFG on income and retirement preparation (see Table 5 for bootstrap results). The indirect effects from Income FSE Retirement Preparation was significant (b = .16, p < .001, CI = .12 and .18) indicating partial mediation. The indirect effects from Income CTAFG Retirement preparation were also significant, but at a lower level of significance (b = –.01, p < .05, CI = –.03, –.00), indicating partial mediation. When FSE increased, so too did the effect on retirement preparation. When CTAFG increased, retirement preparation decreased slightly.

Discussion

Guided by the self-efficacy theoretical framework established by Bandura (1977), this paper tested the mediating effects of FSE on the relationship between income and retirement preparation. We found that both income and the FSE latent variable had significant positive relationships with retirement preparation. This is in line with previous research, indicating that income is significantly and positively associated with savings behavior (Asebedo and Seay 2018), and FSE is significantly and positively associated with savings behavior (Asebedo et al. 2019; Asebedo and Seay 2018; Farrell et al. 2016). The first hypothesis of this research was supported, with results indicating that FSE partially mediated the relationship. This suggested that the effect of higher income on higher retirement preparation was partially explained by FSE.

A notable finding was that CTAFG negatively impacted retirement preparation. This was an unexpected result. In spirit, we believed this survey question on CTAFG aligned with FSE, but clearly, there are differences because its parallel measure, the latent variable of FSE, was positively associated with retirement preparation. How can two operationalizations of the same construct produce significant results with opposite directionality? Past research has shown that retirement planning is positively associated with financial self-efficacy (Asebedo and Seay 2018), while research on confidence indicates a positive association with holding risky assets (Cupák et al. 2020). What is the difference between confidence and self-efficacy? Bandura (1997) himself clarified this question:

“Confidence is a nondescript term that refers to strength of belief but does not necessarily specify what the certainty is about...theoretical system.”

Conceptually, it seems that both the latent variable and the alternative manifest variable, CTAFG, would yield similar outcomes, yet the results implied otherwise. The results suggest that the relationship between CTAFG and retirement preparation was negative and significant. In other words, the more confident respondents appeared to be about their ability to accomplish a financial goal, the less likely they were to be actively contributing to a retirement account.

A possible explanation for this is that financial goal setting is not a skill commonly learned, and it could be misunderstood or misused in practice. As noted in the methods section, the answers to this question were upwardly skewed with the majority of respondents being somewhat or very confident. It is very possible that individuals are overconfident when it comes to achieving financial goals.

Agrawal (2012) acknowledges various ways in which overconfidence negatively affects investment decisions, and these results may suggest that overconfidence may also be associated with underpreparing for retirement. It may be that the latent construct is a better variable to utilize for FSE because it captures a broader array of characteristics and better fits the theory relative to a singular financial confidence question. As such, hypothesis two was supported, but not in the anticipated direction. The mediated association between income and retirement preparation via CTAFG was negative. It is also possible that the survey question on CTAFG did not capture FSE as this study initially presumed. There may also be a difference between CTAFG and taking the logical required action of actively saving for retirement.

What is clear, however, are the results of the latent variable version of FSE. From the confirmatory factor analysis, we found an acceptable method of operationalizing FSE using NFCS data. The SEM results were in line with expectations, indicating that higher levels of FSE are positively associated with retirement preparation. Successfully navigating financial endeavors (mastery experiences), receiving helpful feedback from peers regarding financial matters (social persuasion), and minimizing financial stress (emotional/physiological states) were positively associated with retirement preparation. These three aspects affect an individual’s level of belief in their ability to handle financial matters. The more one believes they are capable of handling financial matters successfully, the more likely they are to actively prepare for retirement.

Implications for Financial Planners

Because FSE is positively associated with retirement preparation, financial planners should not assume that higher income alone will prompt saving for retirement. Instead, clients would benefit from a financial planner’s effort to enhance the client’s FSE. Fostering FSE in clients can be an indirect avenue to enhance retirement preparation. To encourage mastery experiences, financial professionals can remind clients of past financial accomplishments or celebrate with them when a financial goal is achieved. Financial planning software could also be further developed to facilitate mastery experiences by awarding achievement badges to clients as they progress or reach short-term goals.

To encourage healthy emotional and physiological states, financial professionals can model and encourage financial optimism to minimize financial anxiety and enhance financial satisfaction. For social persuasion, financial professionals can teach clients to run a credit report and monitor their credit score regularly. This might be as easy as assisting the client with downloading CreditKarma or a similar phone application to monitor credit. It is an inexpensive value-add that can improve a client’s retirement preparation.

Results suggest that there are critical nuances yet to be explored with CTAFG in regard to retirement preparation. While those nuances were beyond the scope of this study, an implication for financial professionals is to be aware of the difference between confidence and overconfidence. One way to gauge this is to assess your client’s confidence and if they are contributing actively to their retirement account. If they are not, overconfidence may be at play. It is clear that an individual with higher FSE is more likely to prepare for retirement. We also know that overconfidence is not a helpful trait when it comes to personal finances (Kim et al. 2020; Robb et al. 2015).

Limitations

This paper is subject to several limitations. First, more research is needed to understand the nature of the survey question on CTAFG and its relationship with retirement preparation. Second, the NFCS did not offer a suitable proxy for vicarious experience, one of the self-efficacy factors identified by Bandura (1977). Primary data or other data sets may offer options for this element to be studied alongside the other three factors (mastery experiences, social persuasion, and emotional/physiological states). Third, the income data was uneven and ordinal but was converted to continuous data for analysis. While this is a common practice among researchers (Liddell and Kruschke 2018), it can cause inconsistencies and nuances such as the overestimation of inter-factor loading bias and larger standard errors (Li 2016).Different data sets or primary data could be utilized in future research.

Fourth, this paper utilized cross-section data, which limits causal interpretations. Future research could analyze the relationships proposed longitudinally in order to identify causality. Fifth, there is a possibility that endogeneity has not been addressed in this study. Future studies could analyze how other factors, such as risk tolerance, the expectation of an inheritance, or business ownership, would affect the results.

Summary

Results from this study indicate that FSE is positively associated with retirement preparation and partially mediates the association between income and retirement preparation. We found that mastery experiences, social persuasion, and emotional/physiological states in the context of financial matters are positively associated with retirement preparation. Additionally, findings suggest there is an important distinction between FSE and CTAFG. While conceptually similar, they have opposite directional effects on retirement preparation, and they warrant future research.

References

Agrawal, Khushbu. 2012. “A Conceptual Framework of Behavioural Biases in Finance.” Journal of Behavioral Finance IX (1): 7–19.Asebedo, Sarah D., and Martin C. Seay. 2018. “Financial Self-Efficacy and the Saving Behavior of Older Pre-Retirees.” Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning 29 (2): 357–368.

Asebedo, Sarah D., Melissa J. Wilmarth, Martin C. Seay, Kristy Archuleta, Gary L. Brase, and Maurice MacDonald. 2019. “Personality and Saving Behavior Among Older Adults.” Journal of Consumer Affairs 53 (2): 488–519.

Bandura, Albert. 1977. Self-Efficacy: Toward a Unifying Theory of Behavioral Change.” Psychological Review 84 (2): 191–215.

Blanchett, David, Michael Finke, and Wade Pfau,D. 2017. “Planning for a More Expensive Retirement.” Journal of Financial Planning 30 (3): 42–51.

Briggs, Nancy E. 2006. “Estimation of the Standard Error and Confidence Interval of the Indirect Effect in Multiple Mediator Models.” Ohio State University [Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation].

Chatterjee, Swarn, Michael Finke, and Nathan Harness. 2011. “The Impact of Self-Efficacy on Wealth Accumulation and Portfolio Choice.” Applied Economics Letters 18 (7): 627–631.

Cupák, Andrej, Pirmin Fessler, Joanne W. Hsu, and Piotr R. Paradowski. 2020. “Confidence, Financial Literacy and Investment in Risky Assets: Evidence from the Survey of Consumer Finances.” Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

Farrell, Lisa, Tim R.L. Fry, and Leonora Risse. 2016. “The Significance of Financial Self-Efficacy in Explaining Women’s Personal Finance Behaviour.” Journal of Economic Psychology 54: 85–99.

Federal Reserve System. 2019. “Report on the Economic Well-Being of U.S. Houesholds in 2018.” Available at federalreserve.gov/publications/files/2018-report-economic-well-being-us-households-201905.pdf.

Glass, J. Conrad, and Beverly B. Kilpatrick. 1998. “Gender Comparisons of Baby Boomers and Financial Preparation for Retirement.” Educational Gerontology 24 (8): 719–745.

Grable, John, Wookjae Heo, and Abed Rabbani. 2015. “Financial Anxiety, Physiological Arousal, and Planning Intention.” Journal of Financial Therapy 5 (2): 0–18.

Kenny, David A. 2015. “Measuring Model Fit”. Available at davidakenny.net/cm/fit.htm.

Kim, Kyoung Tae, and Sherman D Hanna. 2015. “Do U.S. Households Perceive Their Retirement Preparation Realistically?” Financial Services Review 24 (2): 139–155.

Kim, Kyoung Tae, Sherman D. Hanna, and Samuel Cheng-Chung Chen. 2014. “Consideration of Retirement Income Stages in Planning for Retirement.” Journal of Personal Finance 13 (1): 52–64.

Kim, Kyoung Tae, Jae Min Lee, and JiHyun Eunice Hong. 2016. “The Role of Self-Control on Retirement Preparation of U.S. Households.” International Journal of Human Ecology 17 (2): 31–42.

Kim, Kyoung Tae, Jonghee Lee, and Sherman D. Hanna. 2020. “The Effects of Financial Literacy Overconfidence on the Mortgage Delinquency of U.S. Households.” Journal of Consumer Affairs 54 (2): 517–540.

Kline, R. 2016. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. Fourth Edition. New York, N.Y.: The Guilford Press.

Lee, Yun Doo, M. Kabir Hassan, and Shari Lawrence. 2018. “Retirement Preparation of Men and Women in Their Positive Savings Periods.” Journal of Economic Studies 45 (3): 543–564.

Li, Cheng-Hsien. 2016. “Confirmatory Factor Analysis with Ordinal Data: Comparing Robust Maximum Likelihood and Diagonally Weighted Least Squares.” Behavior Research Methods 48 (3): 936–949.

Liddell, Torrin M., and John K. Kruschke. 2018. “Analyzing Ordinal Data with Metric Models: What Could Possibly Go Wrong?” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 79 (August): 328–348.

Lown, Jean M. 2011. “Development and Validation of a Financial Self-Efficacy Scale.” Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning 22 (2): 54–63.

Martin Jr., Terrance, and Michael S. Finke. 2014. “A Comparison of Retirement Strategies and Financial Planner Value.” Journal of Financial Planning 27 (11): 46–53.

Noone, Jack, Fiona Alpass, and Christine Stephens. 2010. “Do Men and Women Differ in Their Retirement Planning? Testing a Theoretical Model of Gendered Pathways to Retirement Preparation.” Research on Aging 32 (6): 715–738.

Pfau, Wade D. 2011. “Safe Savings Rates: A New Approach to Retirement Planning over the Lifecycle.” Journal of Financial Planning 24 (5): 42–50.

Preacher, Kristopher, and Andrew Hayes. 2004. “SPSS and SAS Procedures for Estimating Indirect Effects in Simple Mediation Models.” Behavior Research Methods, Instruments & Computers 36 (4): 717–731.

Rhee, Nari. 2013. “The Retirement Savings Crisis: Is It Worse Than We Think?” Washington DC: National Institute on Retirement. Available at nirsonline.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/retirementsavingscrisis_final.pdf.

Robb, Cliff A., Patryk Babiarz, Ann Woodyard, and Martin C. Seay. 2015. “Bounded Rationality and Use of Alternative Financial Services.” Journal of Consumer Affairs 49 (2): 407–435.

Shim, Soyeon, Joyce Serido, and Chuanyi Tang. 2012. “The Ant and the Grasshopper Revisited: The Present Psychological Benefits of Saving and Future Oriented Financial Behaviors.” Journal of Economic Psychology 33 (1): 155–165.

Shrout, Patrick E., and Niall Bolger. 2002. “Mediation in Experimental and Nonexperimental Studies: New Procedures and Recommendations.” Psychological Methods 7 (4): 422–445.

Xiao, Jing Jian, Cheng Chen, and Fuzhong Chen. 2014. “Consumer Financial Capability and Financial Satisfaction.” Social Indicators Research 118 (1): 415–32.

Endnote

- Due to this shortcoming in the data and the role as independent variable, income was treated as a continuous measure. Treating ordinal data as continuous is a common practice in empirical analysis (Liddell and Kruschke 2018). As a robustness check, dummy variables were created for income < $50,000, income between $50,000 and < $100,000, income between $100,000 and <$150,000, and income >/= $150,000. The authors reran all the direct paths and got similar results in both statistical significance and directional effect.

Citation

Sturr, Tim, Christina Lynn, and Derek R. Lawson. 2021. “Financial Self-Efficacy and Retirement Preparation.” Journal of Financial Planning 34 (6): 86–98.