Journal of Financial Planning: June 2017

Caleb W. Vaughan, CFP®, is a paraplanner at DMJ Wealth Advisors in Greensboro, N.C. He graduated from the Virginia Tech Financial Planning Program in 2013.

Executive Summary

- Most American households have an age gap of greater than one year between the spouses.

- For couples with an age gap, required minimum distributions (RMDs) will start in different years. This disparity creates an opportunity to maximize late-life portfolio values by maximizing the assets subject to the younger spouse’s RMD schedule.

- This paper identifies numerous strategies to maximize the assets in the younger spouse’s account. The primary benefit of these strategies is that they allow the couple to maximize the tax deferral of the assets by delaying and reducing RMDs.

- Although a surviving younger spouse would typically want to roll the assets into their own IRA, a surviving older spouse may benefit from keeping the assets in an inherited spousal IRA in certain situations.

It has been widely acknowledged that, in most cases, the best use of an inherited IRA for a non-spouse is typically to use the “stretch provisions” to stretch out the distributions over the beneficiary’s life expectancy, rather than taking a lump sum or a five-year distribution (Fidelity 2016; Merrill Lynch Wealth Management 2011). The main principle behind the inherited IRA stretch strategy is that it allows the IRA assets to remain tax-deferred for the longest possible time frame. Therefore, younger beneficiaries, such as grandchildren and great-grandchildren, could stand to receive the greatest benefit from an inherited IRA, because they have a longer life expectancy over which required distributions may be stretched (Curran 2016).

Despite the volume of information related to stretching inherited IRAs, no one seems to have asked the question: “Can an individual stretch IRA assets during his or her own lifetime?”

Technically, it is not possible to change one’s own required minimum distribution (RMD) schedule. However, in a majority of American households, the age gap between the two spouses is greater than one year (Vespa, Lewis, and Kreider 2013). Such an age gap results in many couples having unequal RMD schedules.

The primary objective of this research was to determine whether age gaps created advantages for savings in a younger spouse’s IRA relative to savings in the older spouse’s IRA. Then, if an advantage existed, the secondary objectives were to determine the extent of the opportunity, develop strategies to achieve an optimal outcome, and identify other factors that may weigh on decision-making.

This analysis determined whether the additional year(s) of tax deferral, combined with the lower ongoing RMDs, resulted in an advantage to savings to the younger spouse’s tax-deferred retirement account relative to savings to the older spouse’s tax-deferred retirement account.

Who Would This Affect?

This research is relevant for couples in which one spouse is at least one year older than the other. One might logically presume that, if there is an advantage to saving in the younger spouse’s IRA, larger gaps in age could present greater opportunities to benefit from the advantages provided by additional deferral.

As the first baby boomers (born 1946 to 1964) are now beginning their RMDs, and the rest are at least beginning to think seriously about preparing for retirement, any opportunity to maximize the value of their retirement assets should be of great interest to this particular generation. Nonetheless, younger couples should take notice, because they have the greatest opportunity to proactively position assets in a manner that maximizes additional tax deferral. Implications for seniors who have already reached their required beginning date for RMDs exist, but the greatest value will be realized by those who efficiently structure their accounts prior to retirement.

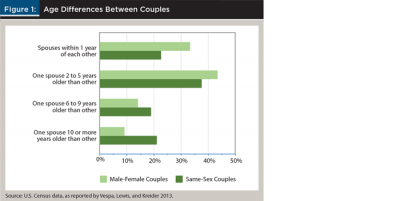

Demographic data collected by the U.S. Census Bureau in 2011 indicated the age difference was greater than one year in 66.7 percent of traditional married couples (Vespa, Lewis, and Kreider 2013). Most of these couples had a difference in age of five years or fewer, but 23.3 percent of all married couples had an age difference of six or more years. When this data was collected in 2011, same-sex marriages were not recognized by the U.S. government; but, for a comparison, the age gap was greater than one year in 77.4 percent of same-sex couples living together. Looking deeper, 39.9 percent of all same-sex couples living together had a difference in age of six or more years (see Figure 1).

Based on the demographic figures, this research may be of interest to most married couples in the United States. It may be especially relevant for the LGBTQ community, because the demographic data suggests that same-sex couples are more likely to have a large age gap than male-female married couples.

Comparison of the Three Life Tables Used to Calculate RMDs

Three life tables are used to calculate required minimum distributions. These can be found in IRS Publication 590-B, Appendix B (irs.gov/publications/p590b): (1) single life table; (2) joint and last survivor table; and (3) uniform life table.

The prior year-end IRA balance is divided by the number retrieved from the appropriate table to determine the RMD. As one ages, shorter life expectancy figures result in smaller denominators, which result in larger RMDs (as a percentage of the account value) being forced out of an IRA. Generally, IRA owners prefer to minimize their RMDs, because this allows them to maximize the duration of the tax deferral. They can always take more than the RMD if desired for tax reasons or if additional funds are needed.

According to Choate (2011): “The divisors in the uniform life table represent the joint life expectancy of a participant age 70 (or older) and a hypothetical beneficiary who is 10 years younger than the participant” (page 46). For most IRA owners, the uniform life table is the most advantageous table, as it allows RMDs to be stretched out based on a life expectancy that is more generous than the joint and last survivor table.

For IRA owners with spouses more than 10 years younger, the joint and last survivor table is used, because it is more advantageous than the uniform life table. The joint and last survivor table provides divisors representative of a second-to-die life expectancy of two individuals using each of their ages. To qualify for this more favorable required distribution schedule, the younger spouse must be the sole primary beneficiary of the account.

The single life table is the least generous of the three tables, because it is based upon the age of the IRA owner alone. This is the table used by IRA beneficiaries. See Table 1 for a comparison of these three tables.

If the IRS wanted RMDs to be actuarially fair, they would use the single life table for unmarried individuals and the joint and last survivor table for all married individuals. This would result in complicated RMD calculations that would be dependent upon not only the age of the IRA owner, but also their marital status and the age of their spouse, if married. However, if this calculation method were used, RMDs would be equivalent for both spouses in any marriage, regardless of potential differences in age.

Perhaps not wanting to deal with the complication, the IRS allowed for use of the uniform life table. This allows all IRA owners to calculate their RMDs as if they are married to someone 10 years younger, regardless of whether they are even married at all. Then, to avoid penalizing couples with a large gap in ages, the IRS allowed the joint and last survivor table to be used by individuals who were more than 10 years older than their spouse.

Therefore, RMDs are structured to provide an actuarial free lunch to anyone who is not married to a spouse that is at least 10 years younger. The greatest benefit of this actuarial free lunch is to unmarried individuals because they get to add an extra life to their calculation, but this benefit is automatic and creates no arbitrage opportunities. The arbitrage opportunity exists for couples whose required beginning dates (RBDs) are in different years—generally couples born at least one year apart. These couples may take advantage of additional tax deferral by maximizing the funds that will be subject to the younger spouse’s RMD schedule.

Maximize Tax Deferral

RMDs begin when the IRA owner reaches age 70½, subject to certain exceptions. Naturally, this means that the younger spouse’s RMDs will begin later, unless an exception applies.

Generally, funds saved in the younger spouse’s IRA will avoid subjection to RMDs for a number of years equivalent to the number of years between the couple (plus or minus one year depending on when each spouse reaches age 70½). Additionally, those assets will be subject to a lower RMD rate when the younger spouse ultimately reaches their RBD.

Therefore, assets in the younger spouse’s IRA have the opportunity to remain tax-deferred for longer and, when RMDs begin, the younger spouse will pull a larger life expectancy figure from the uniform life table. As stated previously, this results in a lower RMD calculation, thereby allowing a greater percentage of these funds to remain tax-deferred than if they had been invested in the older spouse’s IRA.

Maximizing the funds in the younger spouse’s IRA allows a couple to maximize the tax deferral allowed on their retirement assets by subjecting the assets to the RMD schedule of the younger spouse. The following strategies will outline how to maximize the portion of the retirement assets that will be subject to the RMD schedule of the younger spouse.

Strategy No. 1: Saving During Working Years (up to age 70)

After taking advantage of any employer-matching contributions, it typically makes sense to maximize contributions to the younger spouse’s retirement account(s) first, then save any remainder to the older spouse’s account(s).

Example: To control the variables, the data in this example is from a model constructed in Excel. The findings from this research were validated using eMoney Advisor software.

Assumptions:

1. The simulation was run beginning at age 30 for the older spouse.

2. Savings of $18,000 per year were made from age 30 of the older spouse until age 69 of the older spouse.

3. Both spouses were assumed to retire before age 70.

4. The growth rate assumed for both taxable and qualified assets was 6 percent annualized after fees.

5. RMDs, less taxes, were fully reinvested into a brokerage account each year, growing at the same rate as the retirement account.

6. Although RMDs can vary based upon plan-specific rules, RMDs were assumed to be matched to the IRS guidelines outlined in IRS Publication 590-B.

7. The following marginal tax rates were assumed for all years: (1) federal: 39.6 percent; (2) state: 5.75 percent; (3) long-term capital gains: 20 percent; and (4) Medicare surtax: 3.8 percent.

8. The turnover rate for the brokerage account was assumed to be 30 percent annually, with 80 percent of the turnover creating long-term capital gains, and the other 20 percent of turnover creating short-term capital gains.

Assume Mark is 30 years old and is married to a younger woman, Sarah. Mark and Sarah each contribute $18,000 per year to their respective 401(k)s for 40 years, from Mark’s age 30 to Mark’s age 69. The only variable in the following scenarios is Sarah’s age at the beginning of the simulation.

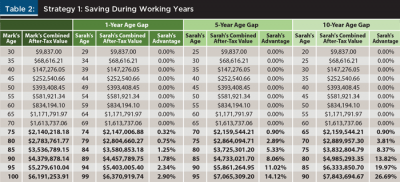

Based on the previous assumptions, these savings would result in the accumulation of two 401(k)s of equal value prior to Mark beginning his RMDs at age 70—one owned by each spouse. When the first RMD is forced out of Mark’s account, we begin to see the advantage Sarah has from the delayed RBD. Assets in Sarah’s 401(k) have extended tax deferral because her RMDs start later. Also, each year when the RMD is calculated, Mark will be ahead of Sarah on the RMD schedule and will be required to draw a correspondingly larger percentage of the 401(k) balance, where the after-tax proceeds are reinvested into a brokerage account.

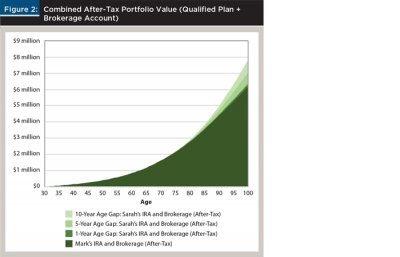

Assume that Mark and Sarah only take the RMDs and reinvest the amount remaining after taxes into a brokerage account. By Mark’s age 100, his accounts would have a lower after-tax value than Sarah’s accounts, dependent upon how much younger Sarah is (see Figure 2 and Table 2).

Based on the additional tax deferral available to the younger spouse, if Mark and Sarah cannot afford to max out their deferrals to both 401(k)s, they should first focus on maximizing the deferrals to Sarah’s 401(k) and making any additional deferrals to Mark’s 401(k).

You will notice, in Table 2, that Sarah’s account values improve for each additional year she is younger than Mark.

If the couple has a one-year age gap, there is about a 2.90 percent advantage to saving to Sarah’s retirement account by Mark’s age 100. The marginal improvement is somewhat reduced for each additional year of separation. For example, the difference between a nine-year age gap (24.34 percent advantage) and a 10-year age gap at age 100 (26.69 percent advantage) is 2.35 percent of Mark’s age 100 value.

With an age gap greater than 10 years, the advantage for Sarah continues to improve, albeit more slowly. Because Sarah would be more than 10 years younger than Mark, Mark would begin to use the more advantageous joint and last survivor tables to calculate his RMDs. In Figure 2 and Table 2, an age gap of greater than 10 years results in the typical increase observed in Sarah’s value at Mark’s age 100. However, it also results in a somewhat offsetting increase in Mark’s age 100 value.

In these examples, the values are exactly the same until RMDs begin. At the older spouse’s age 70, the younger spouse benefits from continued tax deferral of the assets until they begin taking their own RMDs. After the younger spouse’s RMDs begin, their RMDs represent a smaller percentage of their account value each year than the RMDs of the older spouse. This allows the benefits of additional tax deferral to continue to accumulate and compound.

Strategy No. 2: Efficiently Structuring Roth Contributions (up to age 70)

Roth IRAs are not subject to RMDs during the original owner’s lifetime. Therefore, if it is desired that a portion of a couple’s savings be directed to Roth IRAs, it may be advantageous to maximize the Roth IRA contributions for the older spouse and maximize the traditional IRA contributions for the younger spouse.

If the couple is saving to Roth IRAs and traditional IRAs, the older spouse should focus on making Roth contributions, because Roth IRA assets will not be subject to his or her less-advantageous RMD schedule. Doing so allows the younger spouse to maximize his or her traditional IRA contributions, while keeping the same desired overall balance of Roth contributions and traditional contributions for the couple.

If desired traditional IRA savings are not sufficient to max out the younger spouse’s contributions, the traditional IRA contributions should all go to the younger spouse’s IRA first. Then, the Roth contributions may go to either spouse’s Roth IRA, wherever there is space within each spouse’s annual contribution limit. Roth IRAs are not subject to RMDs during the owner’s lifetime; therefore, the age of the spouse who owns the Roth IRA assets is not important for the purposes of RMD arbitrage.

Example: For clarity, consider this example using Mark and Sarah, where Mark is the older spouse:

Mark and Sarah intend to contribute $11,000 to their IRAs this year ($5,500 each). Working with their financial adviser, it was determined that they should direct $3,000 to a traditional IRA and $8,000 to a Roth IRA.

For the purposes of RMD arbitrage, their primary concern should be directing the traditional IRA contributions to the younger spouse’s account. Therefore, Sarah should contribute $3,000 to her traditional IRA. The remaining $2,500 of Sarah’s contribution may be directed to her Roth IRA. Mark’s $5,500 contribution will all be directed to his Roth IRA.

Again, because there are no RMDs during the owner’s lifetime, there is no RMD arbitrage with Roth IRA assets. Therefore, it does not matter that Sarah made Roth IRA contributions, because doing so did not prevent her from making all of the couple’s desired traditional IRA contributions.

Strategy No. 3: Efficiently Structuring Roth Conversions (all ages)

The thought process from strategy No. 2 may also be applied to Roth conversions to maximize their value.

Converting an IRA to a Roth results in the assets becoming tax-deferred for life (no RMDs), therefore, one might consider a Roth conversion a step-up in tax deferral. Similar to a step-up in basis, which has the greatest impact on securities with the lowest basis, a step-up in tax-deferral has the greatest impact when performed using IRA assets with the lowest level of tax deferral. In couples with an age gap, this would be the older spouse’s IRA.

Executing Roth conversions using assets in the older spouse’s IRA removes assets from the older spouse’s RMD schedule and retains assets on the younger spouse’s RMD schedule. Doing Roth conversions this way maximizes the impact of the increased tax deferral as the assets that were previously subject to higher levels of RMDs (due to being in the older spouse’s account) become tax-deferred for life.

Strategy No. 4: Older Spouse with Working Younger Spouse (ages 59½ and older)

If the older spouse is over age 59½ (i.e, he or she can take penalty-free distributions), at least one member of the couple has earned income and the couple cannot afford to maximize retirement savings for the younger spouse, the older spouse could take distributions from his or her IRA to support cash flow. Doing so may free up enough cash flow to allow for offsetting pre-tax savings to the younger spouse’s account.

This effectively creates an indirect transfer of assets from the older spouse’s IRA to the younger spouse’s account, allowing for additional tax deferral of the assets. There should be zero net tax impact if the additional deferrals to the younger spouse’s IRA match the distributions from the older spouse’s IRA.

Strategy No. 5: Post-Retirement Implementation (ages 70 and older)

Couples who are using IRA distributions to fund cash flow should consider withdrawing any amounts in excess of the annual RMDs from the older spouse’s account. This will allow for the younger spouse’s account to continue growing and will create the largest possible reduction in the couple’s future RMDs. Reducing future RMDs increases flexibility in the event the full RMD is not needed in any given year.

Strategy No. 6: Spouse Working Beyond Age 70½ (ages 70 and older)

If one spouse is participating in an employer-sponsored qualified plan, is a less-than 5 percent owner of their company, and intends to work beyond age 70½, they may be able to delay RMDs beyond the standard RBD. If this applies to the older spouse, the above strategies may become less beneficial, as the older spouse will improve their ability to defer. However, if this applies to the younger spouse, the benefits will be magnified due to the additional deferral.

In the event that the plan-participating spouse (older or younger) works beyond age 70½, there may be value in transferring all of his or her IRA assets to the qualified plan prior to the year in which he or she turns 70½, assuming the plan can accept the transfers. If the plan does not allow for in-service distributions, some amount may need to remain in the IRA to support the couple’s cash flow needs until retirement.

Example 1: This example is based on a real-life scenario, incorporating strategies No. 4 and No. 6:

Gary is a 68-year-old retired salesman with no earned income. His wife, Linda, is a 62-year-old professor at a local university, earning a modest income. Currently, their cash flow is somewhat tight; however, in a few years, when Gary reaches age 70, he will begin receiving Social Security and he will begin taking RMDs.

At that time (and throughout retirement), Gary and Linda are projected to have more income than they need to support their lifestyle because Linda plans to continue working. In fact, Linda really enjoys her position at the university and may work beyond age 70. If she continues working, she may delay her RMDs from her 403(b) plan, but her Social Security income cannot be delayed beyond age 70.

The forced income from Gary’s RMDs and both of their Social Security checks combined with Linda’s earnings from work may push the couple into a higher tax bracket. Because they are not expected to need all of this income to support their lifestyle, they would benefit from any strategy that maximizes the assets allowed to remain in the tax-deferred accounts.

Cash flow is a challenge right now, and Linda has not been able to contribute to her 403(b). However, Gary and Linda may support savings to Linda’s traditional 403(b) in a cash-flow neutral and tax-neutral manner by taking offsetting distributions from Gary’s IRA. There should be zero net tax impact if the additional deferrals to the 403(b) match the distributions from the IRA. Additional tax deferral is generated by moving assets to Linda’s account, because she is six years younger than Gary. Plus, if she chooses to work beyond age 70, she may continue deferring the income until she retires.

The couple is projected to have excess cash flow throughout retirement, so significant assets are projected to be transferred to the next generation. The longer the assets remain in the tax-deferred account, the better off the next generation will be, especially if they can stretch the RMDs over their own lifetimes and in lower tax brackets.

Example 2: Let’s continue the example of Gary and Linda, incorporating strategies No. 3 and No. 5:

By “moving” assets to an account with a later RBD, Gary and Linda’s taxable income will be lower than it otherwise would have been at his age 70. If Gary and Linda end up with space in their marginal tax bracket and wish to realize additional income within said tax bracket, they can always do so with a Roth conversion from Gary’s account, per strategy No. 3.

If there is a cash flow need, there is nothing stopping them from taking more than the RMD requires. Per strategy No. 5, this should come from Gary’s account, because it is most advantageous to keep funds in Linda’s account. Although the flexibility this creates is difficult to quantify, there certainly is value in having choices for tax planning.

RMD Arbitrage Creates Flexibility and Control

Implementing strategies to reduce RMDs creates some flexibility by giving a couple more control over what comes out of their IRAs each year. This increases a couple’s ability to manage their annual taxable income, which may open the door for further planning opportunities and tax arbitrage.

For example: (1) tax deferral of assets is improved if the couple does not make withdrawals above and beyond the reduced RMDs; and (2) if the couple is doing Roth conversions as part of a bracketing strategy, the reduced RMDs free up additional space that could be used to perform additional Roth conversions within the same tax bracket.

If additional funds are needed, the couple may still choose to take more than their RMDs, but the key is that the forced withdrawals are reduced.

RMD Arbitrage after First Death

For the following scenarios, assume the surviving spouse is the sole primary beneficiary of the deceased spouse’s IRA. Upon the death of the first spouse, the survivor would inherit the IRA and would have the option to keep the funds in an inherited spousal IRA, or perform a spousal rollover. Generally a few options apply (see IRS Publication 590-B):

Inherited spousal IRA option 1 (original owner died prior to their RBD). RMDs are distributed over the survivor’s single life expectancy using the single life table, recalculated each year. If the deceased spouse died before their RBD, the surviving spouse may delay distributions until the deceased spouse would have reached their RBD.

Inherited spousal IRA option 2 (original owner died on or after their RBD). RMDs are calculated based on the longer of: (1) the survivor’s single life expectancy using the single life table, recalculated each year; or (2) the deceased spouse’s single life expectancy using the single life table, reducing the beginning life expectancy by one each subsequent year.

Spousal rollover. The surviving spouse may treat the inherited IRA as their own. Under this option, distributions may be delayed until the survivor’s RBD and will be based on the uniform life table.

Typically, one would assume an older spouse would die first. Assuming there are no cash flow needs, the spousal rollover is always going to be the best option for a younger spouse to maximize tax deferral of the assets. This provides two benefits: (1) it maximizes the delay on the RBD (to their own age 70½); and (2) distributions are calculated using the survivor’s age and the uniform life table.

In the less likely event that the younger spouse dies first, the ability to keep IRA assets in the name of the decedent potentially becomes a more attractive proposition.

First, consider the case where the younger spouse had not yet reached his or her RBD. In this scenario, because RMDs could be delayed until the decedent would have reached his or her RBD, there will be some number of years where an inherited spousal IRA allows for no distribution, whereas a spousal rollover would have required a distribution based on the surviving older spouse’s age and the uniform life table. Although this allows for the maximum tax deferral prior to the RBD, it also subjects the IRA to the single life table when RMDs eventually commence, which will be less favorable than the uniform life table. When an older spouse inherits an IRA from a younger spouse who has not reached his or her RBD, the surviving spouse should measure the benefit of a delayed RBD relative to the cost of using the single life table to calculate RMDs when they commence.

In the event the younger spouse died on or after their RBD, the inherited spousal IRA option 1 will never be preferable to a spousal rollover, because there is no delay on the RBD. But inherited spousal IRA option 2 may be preferable to a spousal rollover when there is a significant age gap.

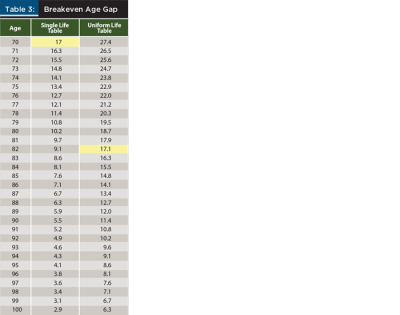

As illustrated in Table 3, the breakeven age gap for the single life table and the uniform life table is 12 years. Therefore, if the younger spouse dies first and there is an age gap of at least 13 years, inherited spousal IRA option 2 could potentially be preferable to a spousal rollover.

However, this evaluation is further complicated by the life expectancy factor reduction of one for each subsequent year when using inherited spousal IRA option 2. This means that each subsequent

year, the factor pulled from the single life table under inherited spousal IRA option 2 will be reduced by one, whereas a spousal rollover would simply look to the next year on the uniform life table, resulting in a reduction of less than one. Therefore, RMDs will grow more rapidly under inherited spousal IRA option 2, causing any tax-deferral advantage for a much older beneficiary to diminish over time.

The benefits of RMD arbitrage generally end at the first death, because in most situations, the survivor will be inclined to perform a spousal rollover. However, in certain situations, RMD arbitrage can create additional efficiencies for the survivor if the younger spouse dies first. This analysis further supports the case for maximizing the assets in the younger spouse’s IRA, as it shows there may be improvements in tax deferral when death occurs to the younger spouse before the RBD and when death occurs to a much younger spouse (minimum 13-year age gap) after the RBD.

RMD Arbitrage Is Not for Everyone

Although the strategies suggested here offer some compelling advantages, in several situations these strategies could create challenges.

Heavy savers. If the couple can afford to max out their contributions to all retirement accounts and all contributions are made on a pre-tax basis, RMD arbitrage may be irrelevant during the accumulation phase. If there are any Roth contributions, see strategy No. 2.

Matching contributions. If the older spouse’s employer makes matching contributions, in most cases it will be more advantageous to maximize the employer match first, then contribute or defer any additional amount available to the younger spouse’s plan.

Divorce concerns. If a couple were to divorce after implementing RMD arbitrage, there would likely be an imbalance of IRA assets. Divorce rates have been steady at approximately 40 percent since 2000, according to the National Center for Health Statistics (cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/marriage_divorce_tables.htm). So, consideration should be given to the likelihood of a potential divorce and how IRA assets would be split in the event of a divorce for any couple considering this strategy. How the assets are ultimately divided may vary case-by-case and according to state law.

Cash flow concerns. If distributions are needed from the younger spouse’s account prior to age 59½, the distributions may be subject to withdrawal penalties. However, these penalties could be avoided using a 72(t) distribution.

Beneficiary designations. RMD arbitrage can make sense if a couple’s beneficiary designations simply send their retirement accounts to the surviving spouse at first death. However, if a couple’s IRA beneficiary designations list any non-spouse as a primary beneficiary, RMD arbitrage may not be viable for the couple.

Frequently, a trust or children are listed as contingent beneficiaries of an IRA. This would not affect the thought process related to RMD arbitrage. However, in a limited number of cases, a trust or children are the primary beneficiaries. A trust may be listed as primary beneficiary to protect the spouse from themselves or potential elder abuse. Additionally, in situations where there are children from a prior marriage, a trust may be in place to ensure the current spouse is provided for during his or her lifetime, but that any remaining assets ultimately pass to the children of the original owner.

In cases where a trust or an individual other than the spouse is listed as the primary beneficiary, protecting assets for the final beneficiaries will almost always outweigh the potential benefits of using RMD arbitrage to maximize the value of the assets—even if the primary beneficiary of the trust is the spouse.

Naming a trust the account’s primary beneficiary complicates the survivor’s ability to take advantage of the spousal benefits of an inherited IRA. Naming a trust the primary beneficiary will generally disqualify the surviving spouse from performing a spousal rollover. In the past, the IRS has issued private letter rulings (PLRs) allowing spousal rollovers from an IRA held in trust. However, according to Jones (2012), “In nearly all such PLRs, the surviving spouse, acting alone, had the ability to orchestrate every aspect of directing the proceeds of the decedent’s IRA to herself.” Therefore, the trusts in these situations do not appear to be structured to protect the account from invasion by the surviving spouse. In situations where mismanagement is a potential concern, asset protection may be a more important consideration than maximizing tax deferral.

In order to treat an inherited IRA owned in trust as an inherited spousal IRA, the trust must qualify as a “see-through” trust and the surviving spouse must qualify as the sole beneficiary (Choate 2011). To qualify as a see-through trust, the following rules must be met, as detailed in Choate (2011):

- The trust must be valid under state law.

- The trust is irrevocable or will, by its terms, become irrevocable upon the death of the participant.

- The beneficiaries of the trust who are beneficiaries with respect to the trust’s interest in the employee’s benefit must be “identifiable…from the trust instrument.”

- Certain documentation must be provided to the plan administrator.

- All trust beneficiaries must be individuals.

Qualifying for treatment as an inherited spousal IRA does not necessarily allow for a spousal rollover of an inherited IRA held in trust, but does allow for the use of inherited spousal IRA options 1 and 2 described earlier. Therefore, if the decedent had not reached their RBD prior to their death, the survivor could delay RMDs until the decedent would have reached their RBD and could spread them out over the survivor’s own life expectancy, which would be recalculated each year using the single life table.

If the decedent had already reached their RBD, distributions would be based on the longer of: (1) the survivor’s own life expectancy, which would be recalculated each year using the single life table; or (2) the decedent’s life expectancy using the single life table based on their birthday in the year of death, reducing the factor by one each year. As explained previously, in most cases, these options will be less efficient than a spousal rollover from a tax deferral standpoint.

Due to the complicated nature of trusts and the potential impact of state law, individuals should consult appropriate legal counsel before naming a trust beneficiary of an IRA.

Conclusion

All other things being equal, couples should do everything possible to maximize the funds in the younger spouse’s traditional retirement account first, then save to the older spouse’s retirement account. By delaying and reducing RMDs, couples gain additional flexibility over their taxable income, reducing the forced taxable income each year. If there is an advantage to realizing income in any specific year, they can always do so—and perhaps do so more efficiently—via a Roth conversion, which adds to tax deferral.

A number of strategies can be used to effect this, including efficient savings structures, efficient Roth conversions, and efficient non-RMD distributions.

When considering the strategies outlined here, keep in mind the other considerations that may be more important than maximizing the tax deferral of a couple’s retirement assets. These can include factors such as potential for divorce, asset protection if there are children from a previous marriage, employer-matching contributions to the older spouse’s retirement account, and any potential need to access funds prior to the younger spouse reaching age 59½.

References

Choate, Natalie B. 2011. Life and Death Planning for Retirement Benefits, seventh edition. Boston, Massachusetts: Ataxplan Publications.

Curran, Geoffrey. 2016. “Demystifying the Stretch IRA.” Online article posted March 17 at merriman.com/wealth-transfer/demystifying-the-stretch-ira.

Fidelity. 2016. “Inheriting an IRA? Spending vs. Investing.” Online article posted December 30 at fidelity.com/retirement-planning/learn-about-iras/inherited-ira-spend-invest.

Jones, Michael J. 2012. “IRS Grants Surviving Spouse’s Individual Retirement Account Rollover Request.” WealthManagment.com, posted June 29 at wealthmanagement.com/retirement-planning/irs-grants-surviving-spouse-s-individual-retirement-account-rollover-request.

Merrill Lynch Wealth Management. 2011. “Stretch IRA Strategy.” Online article at ml.com/publish/content/application/pdf/GWMOL/Stretch-IRA-Strategy_090712.pdf.

Vespa, Jonathan, Jamie M. Lewis, and Rose M. Kreider. 2013. “America’s Families and Living Arrangements: 2012.” U.S. Census Bureau publication P20-570, available at census.gov/prod/2013pubs/p20-570.pdf.

Citation

Vaughan, Caleb W. 2017. “RMD Arbitrage: Strategies for Legally Delaying and Reducing RMDs.” Journal of Financial Planning 30 (6): 49–57.

Author's disclaimer:

Advisory services offered through Investment Advisors, a division of ProEquities, Inc., a Registered Investment Advisor. Securities offered through ProEquities, Inc., a Registered Broker-Dealer, Member, FINRA & SIPC. DMJ Wealth Advisors, LLC is independent of ProEquities, Inc. ProEquities, Inc. does not provide tax or legal advice.