Journal of Financial Planning: July 2014

Financial professionals often employ risk profile instruments to quantify an investor’s ability to tolerate risk. These instruments provide a risk score and often recommend a mix of securities that is commensurate with the risk score obtained. While these profilers are standard in the industry, their validity as risk assessors has been put into question by researchers and financial planning practitioners.

Prominent behavioral economist Dan Ariely believes asking investors to quantify their risk is useless (see his blog post, “Asking the Right and Wrong Questions,” at DanAriely.com). Practitioners have witnessed times when an investor’s risk profile changes based upon mood and market conditions; in other words, it does not remain constant. Many advisers have experienced a situation when an investor has said one thing in a risk profile, and behaved completely different.

It is not uncommon for investors who fill out a risk profile questionnaire to respond in ways they hope to be, not in ways they really are. We do the same thing when courting someone—we project who we hope to become. Investors may be influenced to respond that they can tolerate sizable losses in a down market in order to receive a larger rate of return over time, and retire earlier or with more money.

Asking investors to quantify their desired upside and acceptable downside may yield specious responses because: (1) people often answer “correctly”… that is, what they should do when markets are down, and (2) when not faced with the fear and negative news that accompanies significant market losses, investors don’t realize how bad it will feel at the time.

Research has demonstrated that individuals in a rational state of mind cannot correctly predict how they will react when emotions (and biases) are high.1 Investors may hope to act rationally in the face of bad news and significant losses, but many times they just can’t bear the pain.

Risk profile instruments assume that investors are rational at all times, are not influenced by emotions, and do not make cognitive errors. Harry Markowitz, creator of modern portfolio theory, made the important assumption that investors are rational. However, he then qualified the assumption by saying, “The Rational Man, like the unicorn, does not exist.”2

The assumption of investor rationality is a reason why risk profiling instruments often provide invalid results. For example, many profilers assume that if investors are young and/or have a long-term investment horizon, they can bear more risk and would be given a higher risk score. Risk profilers are good at determining how investors should behave, but do a poor job of finding out how investors will actually behave in real market scenarios, and those often yield entirely different outcomes.

Investors seldom are able to quantify their emotional ability to accept or ride out a loss. Investors may be aware that the market has experienced significant losses in the past, and such losses may occur at some point in the future. However, they may believe (and hope) they will act rationally when the next loss comes, regardless of their past decisions.

If investors sold at the wrong time in the past, they will tell themselves that they have learned their lesson and will do better next time. They may actually believe that this time they can tolerate such a loss. Unless investors are filling out a risk profile instrument when experiencing a correction or a bear market, the fear and anxiety that accompany market drops may not be present, resulting in optimistically skewed responses. In bear markets, financial analysts are often reducing profit estimates, forecasts are pessimistic, financial statements quantify losses, and the media exacerbates the situation by promoting short-term thinking, fear, and anxiety. The news, and corresponding feelings that it promotes, are not conducive to having rational thoughts. Emotions run high in such a situation and may hijack investors’ ability to think rationally, influencing investment decisions that are often contrary to their ultimate investment objective.

Risk Profile Discrepancies

Many quantitative risk profiling instruments are available to advisers. Some may be better than others; however, many of them share the same common problems.

In an academic study I authored at the University of Minnesota,3 I tested a risk profiling instrument used by broker-dealers that was licensed from Morningstar. Besides encountering questions that were vague and could be interpreted differently by distinct individuals, I found that several responses within the risk profile were contradictory to other responses and/or the overall risk profile score. For example, I found:

- 63 percent of respondents who had a “Growth” risk profile, and 68 percent who expected to track the market on the way up, said they could only tolerate “a small loss” in the next three years.

- 55 percent of respondents expected to track the market on the way up, but couldn’t tolerate losses of more than 10 percent in a three-month period.

These findings demonstrate that many respondents wanted to participate in stock market gains with little tolerance for losses. A growth risk profile and/or someone who expects to track the market on the way up would have a significant exposure to risk assets, and therefore should be able to tolerate much greater losses than stated. The key takeaway here is to analyze the individual responses and final risk score; see if there are any contradictory responses along the way, and be sure to clear those up. And remember that investors often answer in ways they hope to be, but you want to know who they really are today.

So what can practitioners do to better assess their clients’ emotional ability to tolerate loss? Advisers should become acquainted with how behavioral biases subconsciously influence investors, in particular when it comes to risk and losses. The following sections offer suggestions to define risk and loss qualitatively, and provide additional understanding and insight to the amount of loss and volatility an investor is emotionally prepared to handle.

With markets near all-time highs and a five-year bull market (as of the time of this writing), this is an opportune time for practitioners to refresh themselves on how investors view risk and implement additional techniques to obtain a more accurate assessment of their clients’ complete risk profile.

Perception of Risk

My favorite question when attempting to understand investors’ attitude toward risk is:

When you consider the word risk, what first comes to mind?

(a) Opportunity

(b) Uncertainty

(c) Loss

This question is important, because you are not asking an investor how much risk they can tolerate, rather you are asking them how they perceive risk—their attitude toward risk. Someone who views risk as an opportunity may welcome investments that are deemed risky or volatile—investments with the opportunity for a good payoff. This response would suggest the investor may be comfortable with a more aggressive allocation to risk investments.

An investor who views risk as uncertain recognizes that some investments may pay off, but others may not. This response is in line with an investor who has a moderate risk tolerance—one who desires some upside, but is also concerned with downside risk. An investor who perceives risk as loss is likely to engage in risk averse behavior, and may be loss averse. This investor would prefer to give up some future profit to not lose much now, which is in line with a conservative investor.

This is an excellent question to confirm (or refute) the calculated risk tolerance found through a traditional risk profile instrument. For instance, if the risk profile found the investor to be moderately aggressive and he answered that he views risk as “loss,” then there may be a problem. The adviser may want to rethink the proper allocation to recommend and, at the very least, ask some follow-up questions to clarify the downside amount the investor can emotionally tolerate—the “threshold of pain.” On the other hand, a response of “opportunity” to the question would confirm a moderately aggressive risk profile, and the adviser could recommend a portfolio of securities with greater confidence.

Loss Aversion

Combining a risk profile analysis with a qualitative perception of risk will provide additional information and a more complete risk profile of the investor. We can take it one step further by attempting to determine whether the investor is loss averse. Studying behavioral biases, such as loss aversion, is an imperfect science; there is no Holy Grail question or set of questions. But these techniques may provide practitioners with greater understanding as to how investors think and feel about investing. The purpose of understanding loss aversion is to better understand how investors may respond to different financial outcomes.

Loss aversion, in a nutshell, is an utter contempt for losses. Individuals who are loss averse feel the pain of loss at least two times more intensely as the joy of an equal size gain. In other words, loss averse investors may require a payout of at least two times the potential loss in order for an investment to be acceptable. Loss averse investors demonstrate risk averse behavior when faced with a gain (lock in the gain), and switch to risk seeking behavior when faced with losses (ride the losses and hope that it will come back).

An academic study analyzed 97,000 prior security trades and found that investors sell winning positions more frequently than losers.4 The study also found that this loss averse behavior resulted in underperformance of 3.6 percent per year versus a strategy of holding winners and selling losers. Loss aversion, if not identified and remedied, has the potential to significantly reduce investment performance.

To obtain a better understanding of the investor’s qualitative risk profile, it is suggested that advisers attempt to identify if their clients are loss averse, and to what degree. A well-known set of preference questions attempts to determine whether an investor demonstrates loss aversion, and a simple payoff question attempts to understand what degree (if any) of loss aversion is exhibited:

Which outcome would you prefer?

(a) A certain gain of $100,000

(b) A 25 percent chance to gain $420,000 and a 75 percent chance of no gain

Which outcome would you prefer?

(c) A certain loss of $100,000

(d) A 75 percent chance of losing $140,000 and a 25 percent chance of no loss

A combination response of (a) and (d) indicates loss aversion. That response demonstrates risk aversion when faced with gain, and risk seeking behavior when faced with losses. Responses (a) and (d) also give the lowest expected value (–$5,000), but it is a frequent response among investors.

The “optimal” response is (b) and (c) because they give the highest expected value (+$5,000). But that “optimal” response assumes that investors are rational—that is, they are not emotional and do not make cognitive errors.

These questions are not foolproof; it is possible for a loss averse investor to select choices other than (a) and (d). It also does not identify to what degree loss aversion is present. To tackle both of those issues, the following simple payoff question may provide additional information. (Note: Other dollar amounts can work here, so long as the expected values remain similar.)

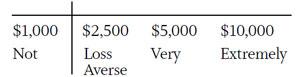

I am going to toss a coin. If it lands on heads you will pay me $1,000. If it lands on tails, I will pay you $__________. What is the minimum amount I would have to pay you to play this game?

In this case, any response less than $2,000 does not indicate loss aversion. According to research, at $2,000 or more we can state the investor is loss averse. The more the investor requires as a payoff, the greater the degree of loss aversion. The greater the degree of loss aversion, the more the adviser should pay attention and incorporate loss aversion into the risk profile of the client. A loss averse investor with a growth risk profile (significant assets in stocks) could pose problems down the road when stocks perform negatively.

Potential Loss Aversion Antidotes

Loss aversion is an emotional bias, meaning it influences how an investor feels. It would be unwise to tell clients that their feelings are irrational or that they shouldn’t feel a certain way. Instead, the bias of loss aversion should be accounted for in the portfolio recommendation. Here are a few suggestions that can be used to account for loss aversion:

Systematic investing. Let’s say a client has deviated from her long-term allocation. The adviser needs to move 20 percent from one asset class to another, but the client is afraid that the second she moves the money, the asset class will experience a quick loss, so she doesn’t act. In this case, the client is afraid of a significant short-term loss. The prospect of a potential loss paralyzes her and is keeping her from the allocation her investment policy calls for. The adviser could recommend moving 2 percent per month for 10 months, alleviating the investor’s fear of a sudden loss upon placing a large amount in stocks at once. The client may be more inclined to follow such a strategy, and the adviser reaches the end goal in 10 months.

Non-correlated assets. This recommendation comes straight from modern portfolio theory, which states that by incorporating non-correlated assets into a portfolio of securities you can reduce the volatility of said portfolio. For loss averse investors, sizeable losses are your enemy. By moderating the volatility, you also reduce the paper losses the client may experience. The goal here is to not exceed your client’s “threshold of pain”—the amount of loss that may influence poor investment choices. Practitioners should be careful to understand the concept of non-correlation. A correlation of 0.65 is not non-correlated. Non-correlated assets should have a very low correlation (positive or negative); the closer to zero the better.

Assurance. Investors who are loss averse, especially those who show a high degree of loss aversion, may find comfort with investments that offer some sort of assurance or guarantee. Some may want to lock in gains, others may not want their account value to go down, and others may just want a guaranteed income stream that is not affected by market performance. Various investment strategies provide these types of assurance. A few examples include CDs, short-term treasuries, and annuities.

Conclusion

Diverse risk profiling instruments will provide advisers with a quantitative score of an individual’s risk. However, those scores often are a reflection of who the investor hopes to be, and may contain contradictory information among the responses themselves and/or the resulting risk score. It is strongly encouraged that financial practitioners begin looking at their clients’ qualitative risk profile. This includes identifying their general attitude pertaining to risk, whether their client is loss averse, and to what degree.

Financial practitioners who take time to understand their clients’ complete risk profile (quantitative and qualitative) will be in a better position to recommend investment strategies that are more suitable for who their clients are today, with the goal of improving investor performance and investor experience.

Endnotes

- See the 2008 book Predictably Irrational: The Hidden Forces that Shape Our Decisions by Dan Ariely.

- Markowitz, Harry. 1959. Portfolio Selection: Efficient Diversification of Investments. John Wiley & Sons. New York. (page 206).

- See The Irrational Investors Risk Profile available at theemotionalinvestor.org/wpcontent/uploads/2012/01/Risk-Profile-Research.pdf.

- O’Dean, Terrance. 1998. Are Investors Reluctant to Realize Their Losses? Journal of Finance (53) 1775–1798.

Jay Mooreland, CFP®, is a behavioral economist and investment adviser representative (www.TheEmotionalInvestor.org). He is a frequent presenter at financial conferences worldwide, educating advisers on the influence of behavioral biases and providing tools that advisers can use to mitigate their influence. He is the creator of the behavioral tools for advisers, Understanding My Client™ and The 9 Habits of Successful Investors™.