Journal of Financial Planning: April 2015

Laura L. Coogan, Ph.D., is an assistant professor of economics at Nicholls State University. Her teaching and research interests include personal saving decisions, labor economics, and public economics. Before her academic career, she worked as a financial consultant to privately held firms.

Shari Lawrence, Ph.D., is an associate professor of finance at Nicholls State University where she teaches a basic investments course as well as a course in personal financial planning. She has numerous publications in the areas of retirement planning, banking, and investments.

Executive Summary

- Workers who have earned a mix of retirement benefits from employment covered by Social Security and from work outside of the Social Security system may face additional complications when estimating their retirement income.

- If these workers have less than 30 years of substantial earnings covered by Social Security, they should expect that their total retirement income will be less than the sum of the income from the two sources; this reduction is due to the Windfall Elimination Provision (WEP), which has been in effect since the mid-1980s.

- For workers in this situation, the Social Security retirement benefit reduction will be based on several factors, including the number of years of substantial earnings under Social Security, the size of the pension (or lump sum) from work outside of the Social Security system, and the age when the worker takes control of the retirement benefits from the outside employment.

- Information about the WEP adjustment is available, but it has not been well promoted. This paper aims to fill that gap by providing links to this information and providing detailed examples of how the WEP is applied to workers receiving non-covered retirement benefits in the form of a traditional pension or as a lump-sum distribution.

Workers who have a mix of earnings and retirement benefits from employment in and outside the Social Security system may face more complexities with respect to retirement planning than if their careers were in one retirement system or the other.

Currently, the most common sources of employment outside the Social Security system include state and local governments that do not participate in the Social Security system, as well as postings outside the United States. For workers whose careers have been split between these two retirement programs, the interaction of the two programs makes estimating a worker’s expected retirement income more challenging, and these job switchers—and the financial planners who assist them—need to understand how non-covered retirement programs interact with Social Security in order to best prepare for retirement. By providing information sources and detailed examples, this paper aims to assist financial planners and their clients in this situation while providing guidance on how to estimate expected retirement income for job switchers.

Specifically, workers who are expecting retirement benefits from employment outside and inside the Social Security system may find that their total retirement income is less than the sum of the benefits from those two programs. The lower total benefit is the result of the Windfall Elimination Provision (WEP), which has been in effect since the mid-1980s. This law applies to workers with retirement benefits from earnings outside the Social Security system regardless of whether their retirement benefits take the form of a traditional pension or a lump-sum payment.

State and local governments may opt out of the Social Security retirement system by providing their own retirement plans. This practice remains common in some areas of the United States. Wages and salaries that are not subject to Social Security tax are called non-covered earnings. According to a 2010 report on pension plans by the National Educational Association, approximately 30 percent of public educators are not covered by Social Security, including many workers in Alaska, California, Colorado, Illinois, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Nevada, Ohio, and Texas. Instead of paying Social Security tax, these workers and their employers contribute to a variety of pensions or market-based retirement plans.

In addition to workers in the education sector, other state and local government workers and individuals who have worked outside the United States may also have retirement benefits from non-covered employment. Meanwhile, workers who pay the Social Security tax have covered earnings that are the norm for private sector and most federal employees.

Impact of the WEP

Currently, more than one million Social Security beneficiaries are impacted by the WEP (Scott 2013), and approximately one-fourth of public employees (or 7 million workers) are not covered by Social Security (GAO 2007). Although the exact number of future retirees who will have enough credits to qualify for Social Security retirement and also receive retirement benefits from non-covered employment is not readily available, it is likely that millions of workers will have earnings from both covered and non-covered employment, and they will ultimately find themselves navigating through a mix of regulations.

While the level of enforcement of the WEP may have been limited or varied in the past, the current application for Social Security retirement benefits includes specific questions that ask if the applicant is entitled to (or will be entitled to) a pension, annuity, or lump sum from work not covered by Social Security (see questions 14(a), (b), and (c) from form SSA-1-BK). Responses to these questions are used to determine if the WEP or the Government Pension Offset applies to the applicant.1

To clarify how the current WEP affects the retirement income of workers with retirement benefits from both covered and non-covered employment, this paper proceeds as follows: after introducing a unique and public source that provided the support for this analysis, a brief summary of the Social Security retirement benefit calculation is presented. That section is followed by an overview of the WEP. The paper then explains the process of calculating retirement income when a worker has both Social Security retirement benefits and a pension (or any multi-period payout) from non-covered employment. This is followed by details of the process when a worker has both Social Security retirement benefits and a single lump-sum retirement payment from non-covered employment. These sections include an example of expected retirement income for hypothetical workers under these conditions. The paper concludes with some guidance for financial planners and their clients in this situation.

This paper presents the current situation with respect to Social Security benefits and the application of the WEP, however it must be understood that these policies may be amended or changed at any time. Although the examples provided contain significant detail, these examples should not be used to give specific financial advice. The specifics of individual situations vary greatly, and the goal of this paper is to provide general information and guidance for workers who have, or are expecting to have, retirement benefits from a mix of covered and non-covered earnings. Although the calculations presented here are relatively straightforward, as with any financial projection, changing a single assumption could produce different results.

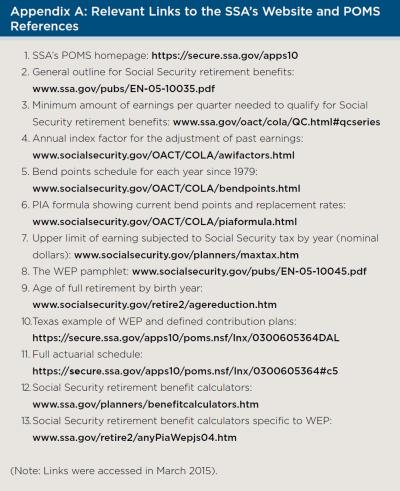

Unique Resource: SSA’s POMS

The Social Security Administration (SSA) maintains a public version of the procedures and information used by Social Security employees to process claims for benefits. This SSA source, the Program Operations Manual System (POMS), provides the technical information and procedures detailed throughout this paper. The links for the information used from this source and the more general SSA website are referenced throughout this paper to links in Appendix A. Additional resources used throughout this paper include appropriately cited publications.

Social Security Retirement Benefits

Information that describes and details Social Security retirement benefits is available on the SSA’s website, www.ssa.gov, and the general provisions are as follows.

When a worker applies for Social Security retirement benefits, the SSA reviews the worker’s earnings history, and if the worker has at least 40 calendar quarters of earnings at or above the minimum required for retirement benefits, the SSA calculates the retirement benefits this worker has earned (see Appendix A, No. 2 and No. 3). After the SSA adjusts earnings from each year to current dollars, it sums the 35 highest years of adjusted earnings and divides that sum by 420 (or 35 times 12) to arrive at the worker’s average index monthly earnings (AIME) (Appendix A, No. 4).

The Social Security retirement benefit, or primary insurance amount (PIA), is then based on the AIME and a tri-level replacement rate schedule. For workers applying for benefits in 2015, the replacement rate schedule is 90 percent for AIME up to $826; 32 percent for AIME greater than $826 and up to $4,980; and 15 percent for AIME above $4,980 to the level of AIME representing maximum taxable earnings (Appendix A, No. 5 and No. 6).2

The breaks in this tri-rate schedule are often referred to as the “bend points.” For example, a worker who turns 66 in 2015 with 30 years of covered, index-adjusted earnings that sum to $882,000 would have an AIME of $2,100 ($882,000 / 420) and a PIA of approximately $1,151 ($826 * 0.9) + ([$2,100 – $826] * 0.32). This worker’s PIA-to-AIME ratio is 54.8 percent ($1,151 / $2,100). Workers with lower AIME (either through lower annual earnings or fewer years of earnings) will have a higher PIA-to-AIME ratio, while higher-earning workers will have a lower PIA-to-AIME ratio.

These Social Security retirement benefits apply to workers with the minimum level of covered earnings. However, for workers who have retirement benefits from both covered and non-covered earnings, it is necessary to understand the WEP in order to more accurately estimate a worker’s net retirement income from a mix of covered and non-covered employment.

Overview of the WEP

The WEP was enacted as part of the Social Security Amendment Act of 1983 with the goal of limiting perceived excessive compensation from Social Security to workers who are qualified for both Social Security retirement benefits and pensions from work not covered by Social Security.3

The WEP only applies to workers with less than 30 years of substantial earnings under the Social Security system. Substantial earnings are greater than the minimum earnings required for Social Security benefits. A link to the table of substantial earnings over time is provided in the WEP pamphlet (Appendix A, No. 8).

The purpose of the WEP legislation was to reduce the benefits received by workers who split their careers and earnings between covered and non-covered employment. This adjustment was deemed necessary as Social Security retirement benefits provide a higher replacement rate when the average of covered earnings is lower. It appears to have been assumed that anyone receiving a pension from non-covered employment would receive a replacement rate from the combined covered and non-covered earnings that were equal to or greater than the replacement rate if all earnings were covered by Social Security. The term “windfall” is based on the apparent higher replacement rate received by workers whose average earnings in the Social Security system were artificially low due to their limited participation under this system.

The WEP applies to workers with retirement benefits from non-covered employment without regard to the form of those benefits. From the perspective of the SSA, non-covered retirement benefits fall into two categories. The first, and the historically more common, is a pension plan where workers receive regular periodic payments throughout their retirement. For workers with a pension, the impact of the WEP is limited to an adjustment of reducing the worker’s Social Security retirement benefits by either one-half of the actual monthly pension paid or by a standardized amount based on the year in which the worker qualifies for Social Security, whichever adjustment is less. Under these conditions, a worker’s combined monthly retirement income from Social Security and the pension cannot be less than the benefits that worker earned from Social Security alone, but the total from the two programs will be less than the sum of the two benefits without the WEP adjustment.

A more complicated situation arises for workers when the retirement benefits are paid in a lump sum, as these workers do not and will not receive a pension from their non-covered employment. This situation is usually the result of a worker who participates in an Optional Retirement Plan (ORP). Although ORPs may appear to have similarities to 401(k) plans, they are unique in that the ORP assets result from non-covered earnings.4

Other reasons a worker may receive all of their retirement benefits at once include a period of employment too short to vest in the pension plan (and the benefit is paid out in a lump sum), or if the worker decides to take the pension benefits as a lump sum. Under this situation, at a specific date (which could be as early as the date of termination from the non-covered employment or perhaps another date based on the specifics of the plan), the worker’s retirement benefits are valued as a lump sum in a market-based account. The procedure in this situation is for the SSA to apply an actuarial schedule to the lump-sum distribution and calculate a monthly pension equivalent. This imputed pension is then used to apply the WEP adjustment without regard to the actual benefit the worker may receive from non-covered employment. In other words, the worker must accept the reduction in earned Social Security retirement benefits without any offsetting income security provided by the non-covered employer.

The WEP and Pensions

Information on how the WEP is applied to multi-period payments (or traditional pension payouts) is available in a pamphlet provided by the SSA (see Appendix A, No. 8) and in a 2005 Journal of Financial Planning contribution (see Mason, Mills, and Ferrell) as well as the previously cited sources. This situation of a combination of a multi-period retirement payout from non-covered earnings and enough covered earnings to qualify for Social Security retirement appears to be the better-known application of this law.

Two calculations are required to estimate how the WEP will be applied to a worker’s Social Security retirement benefits, and the lesser of the two results will be the WEP adjustment.

One calculation reduces the replacement rate within the first bend point of the PIA. Under this application of the WEP, the replacement ratio for the first bend point is decreased from 0.9 to 0.4 for workers who have less than 30 years but more than 20 years of substantial earnings covered by Social Security. The replacement ratio decreases by 0.05 for each year below 30. For example, the replacement rate for a worker with 29 years of covered earnings would be 0.85 (0.9 – [0.05 * (30 – 29)]) while that rate for a worker with 24 years of covered earnings would be 0.60 (0.9 – [0.05 * (30 – 24)]).

For workers who qualify for Social Security retirement benefits but have 20 or fewer years of covered substantial earnings, the replacement ratio is 0.4 at the first bend point. In this “first replacement rate” adjustment option, the other replacement rates at the upper two bend points (of 0.32 and 0.15, respectively) remain unaltered.

The second option under the WEP is an adjustment of one-half of the worker’s monthly pension, and any payment schedule with alternative timing is recalculated to a monthly equivalent. The final WEP adjustment will reduce the Social Security retirement benefit by the lesser of these two options.

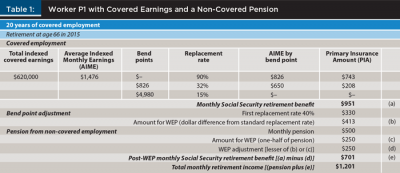

A numeric example of how the WEP would be applied to a retired worker is provided in Table 1. Assume that “Worker P1” had 20 years of covered employment and non-covered earnings that provide a $500 monthly pension. Also assume that he retires in 2015 at age 66, which is the full retirement age (see Appendix A, No. 9). To estimate Worker P1’s total retirement income, the first step is to estimate his Social Security retirement benefits. Assume that the sum of his covered earnings, after the inflation adjustment, is $620,000. This level of earnings produces an AIME of $1,476 (or $620,000 / 420), and the estimated monthly Social Security benefit without any WEP adjustment would be $951.

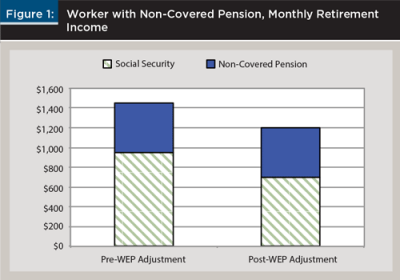

However, as per the SSA rules, the WEP applies to this worker and the adjustment will be based on either a reduction of the replacement rate at the first bend point or one-half of the monthly pension from non-covered earnings. In this example, the first replacement rate adjustment is $413 (when the replacement rate at the first bend point is reduced from 0.9 to 0.4, or $826 * [0.9 – 0.4]). One-half of a $500 monthly pension is $250. For Worker P1, one-half of the pension is the lesser of the two alternatives for the WEP adjustment. To finalize the estimate of Worker P1’s retirement income, the PIA is reduced by $250 for a net monthly Social Security Retirement benefit of $701.

Summarizing these calculations, the initial total monthly payout Worker P1 would receive is $1,201, based on a Social Security retirement benefits of $701 and pension payments of $500 (from the non-covered employer). Without knowledge of the WEP adjustment, this worker may have been planning on a monthly income of $1,451 ($951 in Social Security plus the $500 pension payment). As shown in this example, awareness of the WEP law will help prevent any negative surprises of reduced benefits for workers entering retirement. The estimated monthly retirement income for Worker P1, both before and after the WEP adjustment, is shown in Figure 1.

The WEP and Single Lump-Sum Payment

The WEP also applies to workers who do not and will not receive a pension, but who have earned a lump-sum retirement benefit from non-covered employment. This application of the law is less well publicized, and the only detailed example of this situation that could be located is found on the SSA’s website.

The main source for the calculations below is a 2013 Program Operations Manual System (2013 POMS) update from the SSA that details how the WEP will be applied when a worker’s retirement assets are held in an ORP and/or distributed in a lump sum. The 2013 POMS was based on one of the public retirement systems in Texas, but it offers the best description of how the WEP applies to non-pension retirement assets (see Appendix A, No. 10). The only other source found for use in this study with an explanation of the application of the WEP to ORP participants was described, but not detailed, by the Massachusetts Department of Higher Education.5

The ORP account is considered a lump-sum benefit because at some point in time, the worker controls the assets in the retirement account. According to the 2013 POMS, similar calculations and adjustments would be applied to workers when benefits from more traditional pensions are taken in a lump sum.6

For workers receiving their non-covered retirement benefits in a lump sum, there are two alternatives for calculating the adjustment from the WEP.

The first option is consistent between pensioned and non-pensioned workers, as the WEP adjustment may be based on a decrease in the replacement rate of the first bend point (whereas the replacement rate for the first bend point is reduced from 0.9 to 0.4 as the number of years of covered employment decreases).

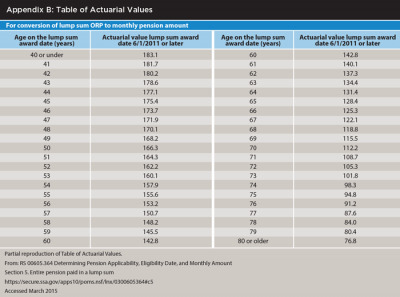

The second option described in the 2013 POMS is a calculation for an imputed pension amount that will be applied to the non-pension assets. This imputed pension is calculated by dividing the value of the asset in the ORP (or the single lump-sum pension payment) on a particular date by a factor that is based on the worker’s age on that date. A schedule that uses the worker’s age on the asset valuation date to provide the annuity factor is partially reproduced in Appendix B (the full schedule is maintained by the SSA).7 The date of which these retirement assets are valued varies based on specific actions by the worker and SSA policies, but one of the key factors in determining the ORP’s valuation date is whether or not the worker maintains non-covered employment.8 This imputed monthly pension is then used to apply the WEP adjustment in the same manner as described above for an actual pension. The final WEP reduction to the Social Security retirement benefits will be the lower of these two options.

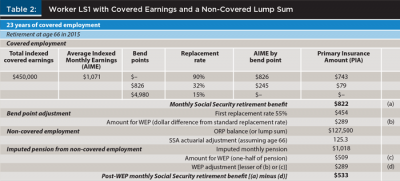

Table 2 shows the calculations for “Worker LS1” who had 23 years of substantial covered earnings that total $450,000 after the inflation adjustment, and who also has an ORP from non-covered employment valued at $127,500 on her 66th birthday, the day she terminated her non-covered employment and applied for her Social Security retirement benefits.

Considering only the covered employment, her Social Security retirement benefits would be based AIME of $1,071, and her PIA would be $822. However, because of the non-covered employment, the WEP adjustment will be applied. In contrast with Worker P1 from Table 1, Worker LS1 has 23 years of covered employment, and the replacement rate adjustment at the first bend point is a reduction of $289 (when the replacement rate at the first bend point is reduced from 0.90 to 0.55, or $826 * [0.90 – 0.55]).

Another option for calculating the WEP adjustment uses her ORP balance of $127,500 and her age of 66. Based on these two factors (and the simplifying assumption that she rolled over the ORP balance to an IRA at the same time)9 her lifetime equivalent of monthly income factor is 125.3. Based on her ORP balance and this factor, her imputed pension is $1,018 (or $127,500 / 125.3), and one-half of the imputed pension is $509.

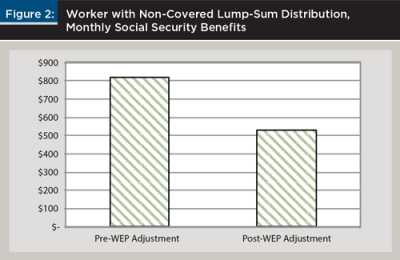

For Worker LS1, the WEP adjustment is based on the first replacement rate adjustment option (which is $289) since this amount is less than one-half of the imputed pension (or $509). After the application of the WEP, her Social Security retirement benefit is $533 (or [$822 – $289]). Therefore, under the current law, this worker has a monthly Social Security retirement benefit of $533 and an IRA with $127,500. This monthly retirement payment from the SSA is only about two-thirds of the amount projected without the WEP adjustment (when Social Security benefits were estimated at $822). The estimated monthly Social Security benefits for Worker LS1, before and after the WEP adjustment, are shown in Figure 2.

This application of the WEP to a lump-sum distribution of retirement benefits from non-covered earnings applies no matter how the worker reinvests these assets. If a worker decides to buy a qualified or non-qualified annuity, the monthly income from the purchased annuity is not used to calculate the WEP adjustment.

Conclusion

The goal of this paper is to explain how the WEP applies to workers who have qualified for Social Security retirement benefits and also have retirement benefits from non-covered earnings. Because of this law, Social Security retirement benefits earned from covered employment will be lowered if the worker has less than 30 years of substantial earnings from the covered employment.

From the SSA’s viewpoint, any worker who has retirement benefits from this mix of earnings sources falls into one of two categories. The first category includes workers who receive multi-period payments (consistent with traditional pensions). The second category is for workers who receive their retirement benefits as a single lump sum (as from a defined contribution plan or as an alternative to a pension).

To help workers and their financial planners navigate this situation, the SSA provides a series of calculators that can be used to estimate benefits, including a calculator that estimates the WEP adjustment for workers receiving a pension from non-covered earnings (see Appendix A, No. 12 and No. 13).

Returning to the previous discussion, the difference between applying the WEP adjustment to the worker with a pension (Worker P1) and the worker receiving a lump-sum payout (Worker LS1), is that the worker receiving non-covered retirement benefits in a lump sum must make an additional calculation. Although the method for the first replacement rate adjustment option in the WEP is the same for both workers, the worker with a non-covered pension must convert the lump-sum assets to an imputed monthly pension based on a schedule provided by the SSA.

Financial planners with clients who have had a mix of non-covered and covered earnings need to take more steps to estimate expected retirement income. One item planners need to inquire about is the Social Security status of current and past employers for workers who have had government employment or who have had periods of employment outside the U.S. For many workers who have earned retirement benefits both under Social Security and outside of that program, the WEP adjustment is a necessary part of their retirement planning.

Workers considering a job change and individuals who have had significant periods of employment in either the covered or non-covered sectors may want to consider the retirement planning implications resulting from any career move that includes a switch between these retirement programs.

Finally, it is important to understand the WEP so that proper planning can be used to reduce a negative surprise of lower-than-expected Social Security retirement benefits. If the WEP adjustment does impact a worker’s retirement, the amount of government-backed, inflation-adjusted income will be reduced, and the worker’s portfolio and retirement strategy may need to be modified to accommodate this situation.

Endnotes

- The Government Pension Offset (GPO) is similar to the WEP in that it may force a downward adjustment of Social Security retirement benefits, but it is applied to spouses with retirement benefits from non-covered earnings. A detailed analysis of the GPO is beyond the scope of this paper.

- Because the AIME is based on earnings covered by the Social Security tax, the upper limit is based on the annual upper limit of earnings. For a schedule of the upper limit of earning subjected to Social Security tax by year see Appendix A, No. 7.

- The legal background of the WEP is sourced from Lipman and Smith (2012), but Brown and Weisbenner (2013) also provided background and information for the calculation of the Social Security retirement benefits.

- Since the late 1980s and early 1990s, many public employers have offered some version of ORPs as an alternative to a pension plan. ORPs are similar to a mandatory defined contribution plan where both employee and employer contribute a portion of earnings to an employee-managed retirement account.

- See the Massachusetts Department of Higher Education website (www.mass.edu/foremployees/orp/ssintro.asp).

- The 2013 POMS also provides guidance for workers who have earned multiple pensions from non-covered earnings.

- The application of the actuarial schedule is described in the 2013 POMS. For the link, see Appendix A, No. 11.

- See section 2c of the 2013 POMS for additional details.

- Rolling over to an IRA triggers the “distribution” of the fund. See section 2c of the 2013 POMS for additional details.

References

Brown, Jeffrey R., and Scott Weisbenner. 2013. “The Distributional Effects of the Social Security Windfall Elimination Provision.” Journal of Pension Economics and Finance 12 (4): 415–434.

GAO. 2007. “Social Security: Issues Regarding the Coverage of Public Employees.” Testimony before the Subcommittee on Social Security, Pensions, and Family Policy, Committee on Finance, U.S. Senate. Statement of Barbara D. Bovbjerg. GAO-08-248T, November 6. www.gao.gov/assets/120/118512.pdf.

Lipman, Francine, and Alan Smith. 2012. “The Social Security Benefits Formula and the Windfall Elimination Provision: An Equitable Approach to Addressing ‘Windfall’ Benefits.” Journal of Legislation 39 (2): 181–337.

Mason, Richard, John R. Mills, and Brian Ferrell. 2005. “Estimating the Social Security Windfall Elimination Provision’s Impact on Clients.” Journal of Financial Planning 18 (12): 52–59.

Scott, Christine. 2013. Congressional Research Service. “Social Security: The Windfall Elimination Provision (WEP).” 7-5700, 98-35, February 15. www.fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/98-35.pdf.

Social Security Administration. 2014. “Form SSA-1-BK (02-2014) ef (02-2014).” www.socialsecurity.gov/forms/ssa-1-bk.pdf.

Citation

Coogan, Laura, and Shari Lawrence. 2015. “Retirement Planning for Workers Impacted by the Windfall Elimination Provision.” Journal of Financial Planning 28 (4): 42–49.