Journal of Financial Planning: April 2015

More than 40 percent of our daily activities are not conscious decisions, but rather habits.1 These daily activities include decisions about investing and other financial choices. People would like to think they analyze every important decision, but the truth is, the brain looks for quick answers. These quick answers are often the result of intuition and/or habit. Habitual thoughts and actions pertaining to the financial markets influence many poor investment decisions.

Financial advisers can play a significant role in helping clients develop better investment habits. This is a value-add approach that advisers can implement to further validate their advisory fee; this is important because the message from the mainstream media is that financial advisers are not worth their fee.2

Robo-advisers are attempting to commoditize financial advice, at least with respect to risk profiling and portfolio recommendations. Teaching and encouraging good investment habits is far more valuable than a simple portfolio recommendation, especially because the average investor is unable to stick with an investment strategy for more than a few years.3 Improving investor habits can encourage more rational, long-term thinking about the financial future.

In this article, I will discuss the psychology behind resolutions, which often has to do with changing one or more habits to obtain a better outcome. I will then explain the nature of habits—how they develop and what steps are needed to change them. Finally, specific investor habits will be examined, along with a practical application of how advisers can help clients cultivate better habits.

The Failure of Resolutions

According to statistics published in the University of Scranton’s Journal of Clinical Psychology, 92 percent of people fail to achieve their New Year’s resolutions. One-third give up just after one month, and more than half give up within six months. This statistic may seem high, but it shouldn’t be that surprising. If we really want to change something about our lives, we would make the change right away. Why would we live our lives in a suboptimal way while we wait for January 1 to make improvements? What is so special about January 1? The sun rises and sets just like every other day of the year. To borrow a line from the movie When Harry Met Sally, “When you realize you want to spend the rest of your life with somebody, you want the rest of your life to start as soon as possible.”

Indeed, if you really want to affect change in your life, you should do it. Waiting for a future date is like saying, “I should improve this, but it’s not important enough to do right now.” Procrastination is not the fruit of someone who wants to change. True commitment often results in immediate change. Many of the things we do, including some of the things we want to improve, are driven by habits. Habits are routines that are ingrained in our brain through frequent repetition, and are often subconscious. If you want to change a certain outcome, there is a good chance a habit (or several habits) will need to change.

Today is a great day to change. Today is a fantastic day to improve your habits to achieve a better outcome. In fact, today is the best day, because it is not tomorrow.

Overview of Habits

Each habit creates a neurological pattern in our brain. It is a physical pathway that is followed once a certain stimulus is presented. This pathway is initially traced by making conscious decisions, but as those conscious decisions are repeated over time, the pathway becomes deeper and the behavior becomes automatic and subconscious. The habit is formed and becomes the default response given the stimulus.

Once we recognize an undesirable habit and want to change it, the process is the same as when the undesirable habit was initially formed. When presented with the stimulus, instead of allowing the automatic habit to take over, we consciously follow a few new steps (the new habit). This is difficult because it takes effort and willpower. We are now doing something that is foreign to us. It can be frustrating and mentally tiring. That is why many people give up after a relatively short period of time. The existing habit has been formed through years of repetition, and we expect that a new habit should take hold in just a few weeks. If it were only that easy.

The Habit Loop

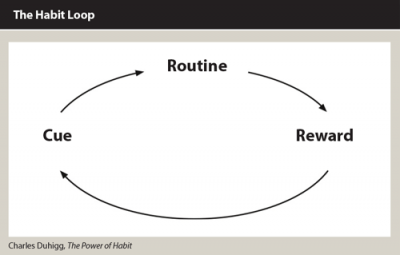

Charles Duhigg, author of The Power of Habit, does a wonderful job explaining how habits work. He simplifies it to three acts: the cue (stimulus); the routine (habitual behavior); and the reward (desired outcome).

Once you understand the workings of a habit, you can define what it takes to replace a bad habit with a good one. Remember, there is a physical neural pathway of the habit in our brain. Although we cannot erase it, we can override it with a new pathway.

Step One: The cue. We need to first understand what cue (stimulus) results in the habitual behavior. The cue is often an external factor that will happen outside of our control (for example, the sun rising). The brain recognizes the cue and responds according to the neural pathway (habit). When learning a new habit, the cue does not change.

Step Two: The routine. If the cue is the sun rising, the routine may be to turn on the shower to get the water warm and brush our teeth while we wait. Think about your morning routine. What do you do first when you wake up? How often do you consciously think about those steps? That is the routine, or habitual behavior. This is the part that changes when learning a new habit.

Step Three: The reward. The reward is the reason we do the habit to begin with. In this example, the reward may be to be clean, smell good and/or to wake ourselves up. The reward can be a physical reward (clean body) or an emotional reward (feel good). The reward does not change.

Replacing Habits

To effectively change or replace a bad habit with a good one, the first place to start is by identifying the desired reward. We may need to look deep. What good thing is the person attempting to accomplish? What is the feeling we are seeking by engaging in the habit? Is it to increase our sense of self-worth? Is it to feel a sense of security? Is it to relax? If we can determine the desired feeling, we can put together a list of more positive actions/routines that will also result in the desired reward.

For example, if Frank has the habit of talking down to others, he may recognize that what he really wants is to feel better about himself. This would require deep introspection and brutal honesty. The next step is to identify the cue. What is it that sets Frank off? Perhaps it is negative feedback from peers, whether it is a family member or his boss. Maybe it happens when he is reminded of his childhood. The cue needs to be identified. Once the reward and cue are identified, we can now move on to more productive behaviors.

When the cue happens, what actions or routines would be more beneficial to Frank and result in him feeling better about himself? There are many potential routines. Perhaps he could go out of his way to compliment someone. He may choose to provide charitable service on a consistent basis (for example, every other Monday). The routines he could follow are diverse. He may select just one or a combination of several new routines to follow depending on the situation.

Improving Bad Investment Habits

You may have clients with bad investment habits. They trade based on short-term outcomes. They check their performance often. They second-guess every decision. They put more weight behind what some TV personality says than they do your advice.

Using the previous outline, let’s figure out how to help an investor replace a bad habit with a good one. The steps in this example can be used for any bad habit that needs to be replaced.

Your client, Jenny, has the habit of wanting to change strategies every time something “significant” happens in the market. Just a few months ago she called you and was contemplating selling all her stocks because of the Ebola outbreak.

You recognize the bad habit and want to help her. The first step is to identify the reward or underlying desire. Upon asking her why she often wants to change strategy, she may say “I don’t want to lose money,” or “I can’t take another 2008.” But if we dig a little deeper and search for the driving feeling, what she’s saying is that she wants to feel secure that she will reach her financial goals. In fact, this is the underlying feeling/reward of many investor bad habits.

The next step is to recognize the cue that stimulates the undesirable behavior. In this case (as in most cases), it could be short-term market losses, expert predictions, and/or the non-stop news about a subject. The reality is all of those cues exist and will likely exist forever. For most investor habits, the cues are out of our control and happen sporadically.

The final step is finding a set of actions or routines that will be more productive for Jenny while it accomplishes the desired reward. What is interesting here is that the desired reward of feeling secure by making short-term changes is an illusion known as the illusion of control. By micromanaging the portfolio, Jenny feels in control and she trusts herself. But the reality is that the more investors trade, the worse they do.4 The problem is that Jenny lacks confidence in the strategy. She doesn’t trust it. She trusts her own intuition and the media more than the strategy.

One potential solution is to make sure she understands how and why the strategy you recommended will help her achieve her financial goals, and if possible, demonstrate how investing based on short-term outcomes reduces the chance of achieving her goals.

You also need to institute a new routine when the cue is present. One possible routine could be that every time she is influenced by a news story or market move, she contacts you to discuss her concerns and, in turn, you remind her of the random nature of short-term market events and how the strategy is going to help her achieve her goals over time.

Another possible routine would be to proactively review the strategy with her on a regular basis irrespective of market events (for example, every three months). You may also want to take the opportunity to remind her how the strategy is expected to achieve her financial goals. Repetition is the key to forming habits. Other routines may work just as well. Simply identify the routine(s) you believe would be best, discuss the desired routines with your clients, and then encourage and praise your clients when they try those new routines.5

Perseverance

Remember that the old habit has been around for a long time—perhaps years or decades. It is unrealistic to expect that a new habit will replace the old one over a period of weeks or months. It will take a lot of repetition and time. Clients need to understand this so they won’t get discouraged.

There will likely be failures and relapses to the old behavior along the way. But failure only occurs when someone gives up. Prior to that it isn’t failure; it’s just that they haven’t succeeded yet. There will be trials. Your job is to encourage and go the extra mile for your client. At times you may be the one carrying the load. If you give up, your client will give up. Be your client’s greatest cheerleader.

As mentioned previously, there is a lot of discussion about the fees financial advisers charge. Many argue that advisers’ value is not commensurate with the fees charged. That may be true for advisers who do nothing more than risk profile and recommend a portfolio of funds. But for advisers who help their clients develop and master better investment habits … well, that kind of advice is almost priceless.

Jay Mooreland is the owner of The Emotional Investor, a company dedicated to providing the tools necessary to anticipate and proactively manage human tendencies by directly improving investor decisions. To request a talk or consultation visit www.TheEmotionalInvestor.org.

Endnotes

- See The Power of Habit by Charles Duhigg.

- See “It’s Time to End Financial Advisers’ 1% Fees,” by Jonathan Clements, posted January 18, 2015 on www.wsj.com.

- See DALBAR’s 2014 Quantitative Analysis of Investor Behavior (QAIB).

- See “Trading More Frequently Leads to Worse Returns” by Charles Rotblut and Terrance Odean published in the November 2014 issue of AAII Journal.

- For habit-specific questions or to discuss in greater detail, contact the author at

jay@TheEmotionalInvestor.org.