Journal of Financial Planning: April 2011

Executive Summary

- Although investment challenges like those experienced in 2008 and early 2009 can result in consumers losing substantial amounts of their investment capital for a time, many consumers lost their homes in the same period as a result of questionable lending practices or a failure by consumers to understand and plan their borrowing decisions.

- This paper proposes the introduction of a “Debt Policy Statement,” modeled off the same principles as an Investment Policy Statement, as a framework for:

- Educating consumers about their “debt portfolio” and the need to manage it to minimize interest costs and maximize the benefits to the family

- Illustrating the risks associated with fluctuations in interest rates, real estate values, and other aspects of the debt portfolio

- Ensuring there is a proper relationship between a client’s risk tolerance and the structure of his or her debt portfolio

- Developing a framework of “debt classes” similar to “asset classes” to help consumers understand the relative costs and risks associated with different types of debt instruments

- Recognizing clients’ future financial goals to ensure short-term advice does not create future limitations that may impede their ability to attain their goals

Shawn Brayman is president of PlanPlus Inc., a Canadian-based firm that provides financial planning software and training worldwide. He has bachelor’s and master’s degrees from York University, Toronto, and is a Chartered Financial Planner. Brayman was the recipient of a Financial Frontiers Award in 2007.

The financial planning principles of debt management have been fairly well understood and articulated for many years. Unfortunately, these principles do not always align with the business reality of firms that sell lending products and want consumers to borrow more. According to the Canadian Banking Association in June 2010, “As much as 51 percent of bank revenues are earned mainly through lending activities.”1 As witnessed in the recent global financial crisis, the creative avenues firms pursue to lend more money can be disastrous for the consumer, the firms, and the economy as a whole.

In the investment management domain, the industry is evolving from “sell what you can that will generate good commissions” to processes for both advisers and consumers that help ensure that the basic principles of diversifying, avoiding emotional trading, and using mechanisms to understand the suitability of investment products are applied in the advice we give. The Investment Policy Statement is the manifestation of this process to provide improved investment advice.

If we search Google for a term such as “debt management plan,” we will receive in excess of 16 million hits. These hits will refer to a plan to help consumers who are “in over their heads” with too much debt. Far more so than investing, lending remains a transactional event to apply for another loan. A holistic view is only taken when trying to bail clients out of overwhelming debt, most often through consolidation of that debt burden on more manageable terms. What this paper introduces is a “Debt Policy Statement” (DPS), modeled off of the established IPS process, to educate and set good debt management policies while supporting institutional and governmental lending policies and best practices.

Objectives for a Personal Debt Policy Statement

Not surprisingly, after 2008–2009, regulators are tightening aspects of the lending process. As outlined by Governor Elizabeth A. Duke of the U.S. Federal Reserve in a press release July 23, 2009:

Our goal is to ensure that consumers receive the information they need, whether they are applying for a fixed-rate mortgage with level payments for 30 years or an adjustable-rate mortgage with low initial payments that can increase sharply. With this in mind, the disclosures would be revised to highlight potentially risky features such as adjustable rates, prepayment penalties, and negative amortization.2

As in the investment arena, a sharp eye is being directed to forms of adviser compensation:

In developing the proposed amendments, the Board recognized that disclosures alone may not always be sufficient to protect consumers from unfair practices. To prevent mortgage loan originators from “steering” consumers to more expensive loans, the Board’s proposal would:

-

- Prohibit payments to a mortgage broker or a loan officer that are based on the loan’s interest rate or other terms; and

- Prohibit a mortgage broker or loan officer from “steering” consumers to transactions that are not in their interest in order to increase the mortgage broker’s or loan officer’s compensation.3

Regardless of how financial planners might aspire to higher fiduciary standards, the majority of the advice consumers receive today is generated by companies with a focus on product sales and profits. Ideally we want to design the personal debt policy statement to benefit all parties. The consumer should benefit from a more considered approach to debt management, and the institutional lenders will be able to institute a more consistent and supportable sales process that supports the tougher rules that will be applied by their underwriting departments, internal auditors, and government bailout partners, allowing increased scrutiny but in a context of value-added advice.

The steps in an investment policy statement are:

- Collect factual information about the client

- Perform a risk tolerance assessment

- Determine investment objectives or goals

- Analyze the client’s current portfolio

- Potentially propose a new portfolio structure

- Recommend specific investment products to implement the proposed portfolio

- Periodically rebalance the portfolio and/or complete a full review of the investment policy statement

We want to follow similar steps in the debt policy statement:

- Apply the lending criteria demanded by regulators and used by the industry

- Be sensitive to clients’ goals, risk tolerance, and other resources

- Apply the financial planning principles on how debt should relate to our life stages

- Create a “debt portfolio” that is appropriate to the individual

- Quantify the benefits of any restructuring of the debt portfolio so clients can clearly understand their current situation as compared with the recommended strategy

- Be sensitive to the fees and costs that will be associated with the implementation of the strategy

The DPS should provide advisers a framework that can assist in recommendations appropriate for specific clients not based on whether they can qualify for what they asked for but whether what they asked for makes sense for the clients.

A traditional loan application provides the measures about qualification for assuming debt and requires some basic information to be collected:

- A review of the net worth statement to understand the assets and liabilities currently owned or owed by the client

- The costs for servicing the debt that is already in place

- Income and fixed costs that may affect the client’s cash flow, such as property tax on a home

Risk Tolerance Assessment

Many firms struggle with performing a proper risk tolerance assessment for investment planning and may revert to either a simple selection—“the client is moderate”— or create questionnaires that have so few questions or such poor questions that the result of the exercise is of little value.4 Is there any value in understanding a client’s risk tolerance in a lending exercise?

Debt is a magnifier of risk when considered relative to the volatility of investments and generally adds levels of risk to the ability of individuals to achieve their financial goals. The logic that tells us there is an association between the clients’ risk tolerance and their comfort in assuming risk in a portfolio should hold true with the assumption of debt.

Research by FinaMetrica, a leading psychometric risk-profiling provider, has shown that financial risk tolerance is a single attribute of an individual, much like an IQ, and there are no sub-factors.5 The good news is that if we apply a proper psychometric test in the determination of risk tolerance for investing, exactly the same measure is relevant in other financial aspects of the client’s life. It will not be necessary to generate a separate risk tolerance assessment for lending.

As in investing, the question will be how the risk tolerance is applied to the debt policy decision. Some additional questions we want to determine are:

- How good are the clients at managing debt? If they do so poorly, do we need to lock things down as opposed to establishing credit lines?

- Are there other types of risk to income from poor health, loss of a job, and so on that could endanger their ability to earn income?

These factors will have an impact on the strategy we recommend.

Understanding Clients’ Current and Future Financial Goals

Unless it is an immediate goal that will relate to the assumption of additional debt at this time (for example, “We want to buy a new car”), why is it necessary to understand both the clients’ current and future financial goals? By definition, “planning” is intended to allow clients to take actions today that will lay a better foundation for their financial goals in the future.

As with an investment portfolio, there are direct costs related to how we structure and subsequently re-structure a debt portfolio. If we make decisions and recommendations this year without understanding the future consequences, it can lead the clients into conflicts that are expensive to resolve. As an example, suppose a couple wanted a new boat this year and they also have one or more children going off to college in three years. The decision to borrow today for the boat may compromise the ability of the clients to borrow funds in the future to assist the children with their education.

As such, another important building block in a debt policy statement should be gathering and prioritizing current and future financial goals. How much is required, when, and for how long? What investment resources might exist to help achieve these goals and, in their absence, what other resources including debt can we use?

The use of debt is an expediency to allow clients to achieve important goals in advance of accumulating significant capital, but eventually clients should own assets unencumbered by debt. Ideally, clients should be debt-free by the time they retire as the cost of borrowing will usually exceed what they can earn on the fixed-income portion of their portfolio.

Establishing Debt Classes

There are a series of “debt classes” into which we can categorize existing and proposed debt to better understand our alternatives. A nice side benefit to following a similar format to an IPS is the ease with which advisers can communicate this to the client. If clients have already been educated by way of an investment policy statement, they will grasp the principles of the debt policy statement more quickly.

In an IPS we might have cash, one or more types of fixed income, and a few equity asset classes such as domestic equity, global equity, real estate, and so on. Can we categorize debt in a similar approach? As in the investment world, there are many approaches that can be taken; I will outline one here:

- Credit Card Debt—the “small-cap equity” of the debt world. Credit card debt is traditionally not secured, subject to very high interest rates, and by its nature a higher risk for the consumer.

- Unsecured Lines of Credit—another form of consumer debt often used for lifestyle expenditures. The interest rates are usually better than credit cards.

- Debt on Depreciating Assets—loans associated with assets that will depreciate in value over time, like cars and boats. This type of debt is usually subject to more moderate interest rates and risk as a result of the security of the asset. It usually has a fixed amortization at a rate faster than the expected depreciation on the asset.

- Debt on Appreciating Assets—financing used for the acquisition of a fixed asset, such as a home or cottage, that is expected to grow in value. This type of debt, especially as it relates to a home mortgage, tends to have the lowest interest costs and is usually perceived as the lowest level of risk. We need to differentiate between secured lines of credit and mortgages with fixed rates and amortizations, as these have different levels of risk associated with them and will have different effects on interest rate sensitivity analysis.

- Debt on Income-Earning Assets—loans used for the acquisition of income-producing real estate or other investment assets. Issues of deductible and non-deductible debt may arise.

- Equity—not really a debt, but when looked at in the context of net worth, the ultimate and preferred asset class. Equity has no cost and reduces risk, similar to the risk-free cash return in an investment portfolio.

It is important when we categorize debt to consider the use of the funds, not simply the nature of the debt. If we consolidate consumer debt into a line of credit secured by a home, it may reduce the cost of borrowing, which has some value, but not if the only effect is to clear off credit cards that are then taken back up to their limits to fund lifestyle.

As with investment assets, there are rates associated with these “debt classes,” risk associated with the volatility of the interest rates on funds we borrow, and volatility on the value of the assets that secure the loans. As with a strategic allocation statement, the DPS should look at how a debt class is structured relative to the other classes.

A Client Example, Displaying the Current Debt Portfolio

To provide some context, let’s consider a couple about 35 years old who:

- Own a home now valued at $330,000, with $300,000 remaining on their mortgage over 25 years. The mortgage is at a fixed 5 percent interest for the next five years, at which time it must be renewed.

- Have multiple credit cards with outstanding balances of $15,000 at 20 percent variable interest rates.

- Have $30,000 in investments.

- Have a $40,000 car with $35,000 financed at 8 percent fixed over the next five years.

- Have two children ages seven and five. They are saving a small amount for education, but feel they will need to borrow at least $10,000 annually for each child to assist with their education costs through four years of college.

- Want to buy a boat after they have supported the kids through school. The boat today would cost about $50,000, and the husband figures they will need to finance about 75 percent of the cost.

- Have a combined income of $100,000 per year with inflationary increases.

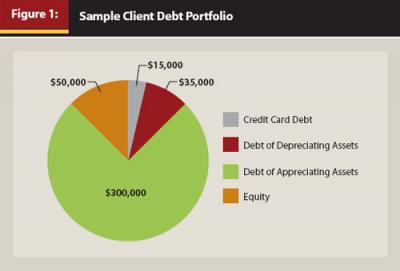

The net worth information we gathered on these sample clients can be used to generate an initial display of their current debt portfolio. In presenting the debt portfolio, we may want to show each of the debt classes and how much money is owed under each type (see Figure 1), and what the average interest rate experienced with the debt class might be. Ideally we would also have a simple indication of the risk level associated with each class of debt.

Lending Metrics

A variety of metrics has been developed to allow investors and accountants to better understand the balance sheets of the companies in which they invest. There are also a few that have been developed specifically for consumer-based lending that can help an adviser assess a client’s debt health.

- Gross Debt Service Ratio—the cost of owning a home divided by gross income. Generally this limit is placed between 32 percent and 35 percent. Example: (loan payments + insurance + property tax) / gross income.

- Total Debt Service Ratio—all debt service payments divided by gross income. Limits of 40 percent by lenders might be expected.

- Interest/Payments—it is important to differentiate between clients who are paying 100 percent interest and no principal versus those retiring debt. Two clients might have identical total debt service ratios, but if one was paying interest only and the other had a short amortization, the latter would be in better shape. A ratio of 100 percent would be very bad; 0 percent would be only repayment of principal.

- Debt Ratio—total liabilities divided by the total assets. Below 40 percent is good, higher than 40 percent needs to be supported by appropriate fixed assets, and above 70 percent is very high.

- Current to Total Liabilities—ratio of liabilities due in the next 12 months divided by the total liabilities. The shorter the amortization on a loan, the more of it that will be due in the next 12 months. Credit cards would always be considered current. A higher number is usually considered poor, but it must be considered in conjunction with other measures. Consider clients who will pay off their mortgage in the next 12 months! They would have a very high current to total liability ratio, but that would be excellent.

- Credit Used Ratio—take the balance outstanding on all credit cards and revolving accounts, like a line of credit, and divide by the available limits on these instruments. A result of 1 (or 100 percent) means the clients have used all their available credit. A result of 0 percent means they have all of their credit available to use.

It is the combination of metrics that gives an effective measure of overall debt management health and direction. There are so many lending instruments that rob Peter to pay Paul that only a combination of metrics will tell the true story.

Back to our client example, let’s look at what happens when we not only apply the key lending metrics on the current debt portfolio but project the debt repayment and apply the new goals that require debt financing as outlined above.

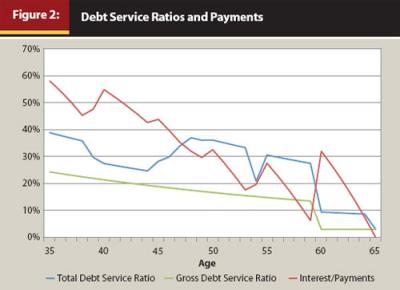

In Figure 2, we can see that the gross debt service declines over time as the salary continues to index. After 25 years, the mortgage is retired. The total debt service declines, then jumps back up to fund the kids’ education and again to finance the purchase of the boat, but remains in a reasonable range.

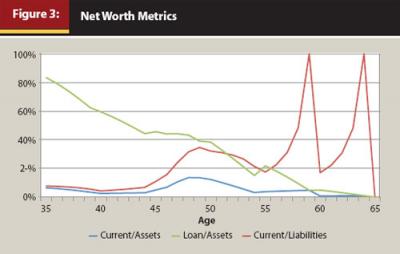

When we look at some of the net worth metrics in Figure 3, we can see that the debt ratio (loans/assets) continues to improve over time. As the size of the mortgage declines and the kids’ education and boat are financed, the current-to-total-liabilities ratio will increase.

Debt Risk Considerations

Interest Rate Risk. One of the key risks assumed by clients in the use of debt is the interest rate risk in the event that rates increase. There are a few factors we can look at and draw to clients’ attention:

- The weighted-average term on the debt indicates how long the client has before rate increases would have an impact on their lifestyle. Fixed-rate loans such as a mortgage or car loan would be stable until the term expires, while variable-rate loans would be immediately subject to risk.

- The total principal to repay is fixed and depends on current liabilities and future goals that require new loans. Changes in interest rates will not alter this, but they will change the total interest paid, and therefore the total payments and the impact on cash flow. On the mortgage, a change in rates only applies at renewal.

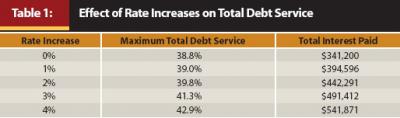

- As we see in Table 1, increases in the interest rate could increase the maximum total debt service of the clients above the supportable limits, forcing a reduction in the amount that can be lent or extending amortizations at higher interest rate costs.

- If we look at historical inflation, cash rates, and fixed-income rates over the past 60 years,6 we see that current rates are definitely at the low end of the range:

Inflation—3.8 percent ± 3.2 percent

Cash—5.8 percent ± 3.9 percent

Long-term fixed income—6.7 percent ± 8.5 percent

Although we know that historical returns provide an understanding, they are not a basis on which to predict the future. Nonetheless, they would definitely support the view that higher rates in the future are very possible.

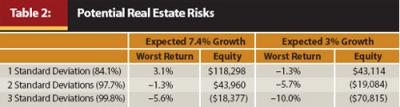

Real Estate Value Risk. There is a negative correlation in most markets between mid- and long-term fixed income rates and real estate (for example, a –0.12 correlation from 1950 to 2009). In other words, if mortgage rates increase, real estate values drop. Investment real estate has had a return of 7.4 percent with a standard deviation of 10.6 percent.7 When the mortgage renews in five years, depending on if we assume the home has an expected growth like investment real estate or just an inflationary rate, we would see the results provided in Table 2.

In this case we only care about the downside risk. The five-year period has allowed the clients to pay down the mortgage (as we can see in Table 2, there is an 84.1 percent chance with 1 standard deviation), but their equity will have increased from $30,000 to $43,114 or better. Nonetheless, there is a chance it may have declined from 5.6 percent to 10 percent or more per year in value. In this event the balance owing on the mortgage in five years would be $70,815 more than the value of the home. Possibly a value-at-risk illustration might be more easily understood by the client.

Generating a Proposed Debt Portfolio

In evaluating how we structure a proposed debt portfolio for clients, the primary objectives are to reduce the overall expected cost of borrowing and reduce the risk to which the clients may be subjected as a result of interest rate changes. We want to ensure that the level of risk is reasonable given the clients’ risk tolerance.

Some assumptions:

- Consolidating or changing the nature of debt will not affect the debt ratio; it will only affect the gross debt service or total debt service if we use the changes as a mechanism to reduce the payments as opposed to reducing the amortization. With such a recommendation we should display a before/after picture of the key metrics.

- Let’s assume that any consolidation must not reduce the principal repaid over time (in other words, we do not take short-term debt and make it long-term debt).

- We need to establish the value of the next dollar saved versus the next dollar of debt repaid. Whether from debt consolidation or at the conclusion of paying off another debt, do the clients accelerate payments on remaining debt or save the difference? Let’s assume that the recommendation is not to have the excess cash flow simply fall back into lifestyle expenses.

- Establish business rules to limit the number of credit cards and the credit limit on credit cards. Assume two months’ gross income as a reasonable maximum. Assume all credit cards are for convenience, not financing.

- Move unpaid credit card debt to an unsecured line of credit at better rates, or move lines of credit to secured lines of credit with best rates.

- Calculate the available debt against appreciating assets (for example, the home) to determine the ability to consolidate into a secured line of credit versus an unsecured line. In most cases, a secured line of credit will be limited to 75 percent or 80 percent of the appraised value of the home. Assume that once the equity in the home exceeds 50 percent, either from repayment of principal or appreciation in value, this may be an option.

- This is the stage at which we need to consider the risk tolerance of the clients when combined with the understanding of interest rate risk and real estate risk. When we have clients with a lower risk tolerance, do we consider recommending a lower total debt service/gross debt service threshold or a higher down payment on real estate? As with investing, it does not limit the clients from undertaking whatever they qualify for and desire, but as advisers we are meeting our obligations to the clients by drawing potential risks and conflicts to their attention.

Depending on the life stage of the clients, the flexibility on what can be recommended at the current time may be limited by their equity and key ratios. Especially in early stages with current or recent acquisitions of homes, options may be limited to simple unsecured lines of credit to clear up credit card debt. A more important aspect may be the longer-term strategy and recommendations.

Implementation and Recommendations

As with an IPS, we could recommend to clients that the actual strategic model they have in place is fine, but make some recommendations for changes in the products used to implement the model. More frequently we use changes in the asset classes as the triggering event to recommend new products.

As an example, our recommendations may include:

- An immediate unsecured line of credit and no other immediate changes.

- Strategically, we might suggest that as the value of the home increases and principal is repaid, to, in about 10 years, put in place a secured line of credit to help finance the kids’ education, the cars, and the boat.

- Many all-in-one accounts promote the application of low return savings against higher interest debt with a secured line of credit. If the client may need to use this for emergency funds in the future, we need to assess whether the credit remains available in the event of job loss.

- The recommendations should address the need for appropriate life and disability insurance coverage in general, but for liability coverage in particular.

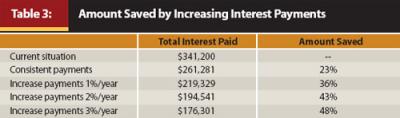

- We might recommend that the client maintain consistent payments where, as some debt is retired, the payments are redirected to accelerate other debt repayment or possibly toward debt service if additional loans are assumed for future goals. This might remove increases in future debt service and allow a steadily declining total debt service ratio and lessening impact on lifestyle.

- An alternate strategy might be to increase future payments in line with increases in salary. As we can see in Table 3, if we assume salaries are indexed at 3 percent and loan payments are indexed at 1 percent and redirected to alternate debt as possible, it results in more than 36 percent less interest paid by the client.

- The debt strategy is also a key to the financial plan. Although accumulation remains a preferred strategy, the debt strategy is inextricably linked to the ability to achieve the financial goals of the client and is often ignored by advisers.

If a client has a strong debt strategy in place, reviews are still a part of the overall planning process, although very little may change year to year. For those without good debt management skills and behavior, the annual review may be instrumental in addressing issues before they escalate out of control. Either way, it remains critical that the financial planner help clients maintain their plan and avoid the common problem of allowing other financial pressures to derail the plan in place.

Conclusion

This paper looked at a defined process that can be built from processes already familiar to planners and a growing number of clients. The recommendations are:

- Introduce the concept of a personal debt policy statement, either as part of a financial plan or in isolation as part of the debt management process

- Include clients’ risk tolerance in the process, along with the future goals that may require debt financing

- Determine standard “debt categorization” or classes to allow clients to differentiate on the cost and risks associated with debt instrument choices

- Help clients understand and visualize their financial future, including the risks associated with their current or a proposed approach to debt

- Have well-defined business rules that lead to a proposed debt policy and use of classes of lending instruments with clients

- Encourage behaviors that are to clients’ ultimate betterment, such as accelerated debt reduction

- Provide other advisers and institutional lenders a framework to articulate best practices on debt management for clients and to ensure some consistency and objectivity in the recommendations of policy and debt products to clients

Endnotes

- Canadian Banking Association: www.cba.ca/en/media-room/50-backgrounders-on-banking-issues/119-bank-revenues-and-earnings-profits.

- Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System: www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/press/bcreg/20090723a.htm.

- Ibid.

- Roszkowski, Michael J., Geoff Davey, and John E. Grable. 2005. “Insights from Psychology and Psychometrics on Measuring Risk Tolerance.” Journal of Financial Planning (April).

- FinaMetrica: www.riskprofiling.com.

- Based on Government of Canada CPI, 91-Day Treasury bills, DEX Universe Bond from 1950 to 2009. Over the past 30 years U.S. CPI was very similar at 3.91 percent +/– 2.89 percent and U.S. 192-Day T-bills were 5.70 percent +/– 3.23 percent.

- Based on an aggregate index of the Morguard Fund, Russell Real Estate, and Globe Real Estate Peer Index between 1950 and 2009.