Journal of Financial Planning: May 2025

Brendan Pheasant, CFP®, ChFC, is a financial planner with Tuyyo Planning Group, LLC (https://tuyyoplanning.com), and a doctoral student in personal financial planning at Texas Tech University. Brendan’s vision is intelligent, academically based, well-being-centered financial planning.

Christina Lynn, Ph.D., CFP®, AFC, CDFA, is a director and wealth strategist at Mariner (www.mariner.com). She trains wealth advisers in financial psychology, estate planning, and divorce finances. Through motivational interviewing, she empowers advisers to build emotional intelligence and elevate the client experience.

Click HERE to read this article in the DIGITAL EDITION.

JOIN THE DISCUSSION: Discuss this article with fellow FPA Members through FPA's Knowledge Circles.

FEEDBACK: If you have any questions or comments on this article, please contact the editor HERE.

NOTE: Click the figure below for a PDF version.

Differentiating and supporting the right kinds of client motivation is a subtle yet powerful tool for enhancing client success and well-being. We often think of client motivation as how much someone wants to take action, but research shows that why someone is motivated can be more important than how much they are motivated (Ryan 2023). When financial behaviors are driven by autonomous motivation, doing things voluntarily because one enjoys or otherwise values the activity, one tends to experience better financial outcomes, such as responsible spending, saving, and borrowing, as well as increased overall well-being, including greater vitality and life satisfaction (Di Domenico et al. 2022). On the other hand, when financial behaviors are driven by external pressures, like guilt or fear, people are more likely to feel depleted and experience poorer financial and personal outcomes (Di Domenico et al. 2022). Financial planners can support their clients’ well-being and the cultivation of healthy financial behaviors by learning how to foster autonomous motivation. This article examines (1) the types of motivation, (2) research on supporting autonomous motivation, and (3) motivational interviewing as a practical solution for incorporating these insights into practice.

Why Motivation Matters in Financial Planning

When people lack motivation, they don’t take action because they either don’t see the value in it or don’t believe they can make a difference. Motivation is what drives us to act, yet it can come from many sources. Being chased by a lion, smelling freshly baked chocolate chip cookies, or noticing your child’s bike helmet is cracked are all motivating experiences—but they vary widely in our physiological response and how we would feel when engaged in the activity.

Types of Client Motivation

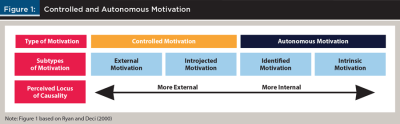

Self-determination theory (SDT; Ryan and Deci 2000; Ryan and Deci 2017) provides a framework for understanding these different types of motivation based on where the motivation is perceived to originate (see Figure 1). From left to right, motivation begins with a sense that one’s reasons to act come completely from external sources, becoming increasingly internal as one progresses through each type. The four subtypes of motivation are also categorized into controlled and autonomous motivation.

Autonomous Motivation

With autonomous motivation, people feel like they want to do something. This usually happens for one of two reasons: they either enjoy the activity or find it important. When someone does something purely for enjoyment, it’s called intrinsic motivation. On the other hand, when they do it because they believe it is important, it’s called identified motivation. Suppose someone spends a Saturday morning doing a crossword puzzle for fun; that is intrinsic motivation. However, if one did the same crossword puzzle to keep their mind sharp, that’s identified motivation. The activity is the same, and in both instances, the motivation stems from within, but the reasons are different.

Identified motivation is particularly powerful. It is associated with increased performance (Van den Broeck et al. 2021), engagement (Howard et al. 2021), prediction of effort (Howard et al. 2021), and continuance commitment (Howard et al. 2021; Van den Broeck et al. 2021). This is important because many clients may not find financial planners’ recommendations inherently enjoyable (i.e., not intrinsically motivating). Thus, identified motivation is a valuable form of autonomous motivation for financial planners to nurture in clients, as it could be a primary driver of lasting, self-directed financial behaviors.

Controlled Motivation

Conversely, controlled motivation is characterized by feeling pressured to do something rather than wanting to do the activity. As with autonomous motivation, it also has two main drivers: doing something to gain a reward or avoid a punishment, or feeling like you “should” do it. External motivation is when actions are driven by outside consequences, like avoiding a speeding ticket or earning a bonus. This type of motivation is often short-lived—once the reward or punishment is gone, so is the motivation.

Introjected motivation is different. It comes from internal pressure, often from guilt, shame, contingent self-worth, or a sense of obligation. While it might feel like it’s coming from within, the motivation is still based on avoiding negative feelings rather than a genuine desire to act. Because of this, introjected motivation can be mistaken for identified motivation. The key difference is that with introjected motivation, people act out of a sense of “I should” rather than truly valuing the activity. For example, a client might say they’re motivated to create an estate plan, but their motivation could stem from feeling ashamed for not having one, rather than believing it’s personally important.

Controlled motivation may get some results, but it is generally a less desirable form of motivation. In the case of external motivation, if the reward or punishment disappears, so does the motivation to act. With introjected motivation, if the client acts on their estate plan, they may be more likely to seek out the easiest, cheapest alternative, such as an online cookie-cutter will, because they don’t fully see the value of having an estate plan.

How to Support Autonomous Motivation

How do financial planners support autonomous motivation in clients? The short answer: through autonomy support. In the context of financial planning, the study of autonomy support is about understanding how interactions between the financial planner (or firm) and the client (Asebedo 2019) support autonomous motivation (Ryan and Deci 2017). While autonomy support has not been widely studied in financial planning, it has been in other fields, such as medicine, sports coaching, and education. Financial planners can enhance their practice by applying proven insights from these fields to support client autonomy.

Perhaps counterintuitively, being autonomy supportive doesn’t necessarily mean a financial planner is not also being controlling. Research shows that motivation styles can be both autonomy supportive and controlling, or neither (Haerens et al. 2018). While autonomy supportive styles tend to boost autonomous motivation and overall well-being, controlling styles have the opposite effect, increasing controlled motivation (Haerens et al. 2018). Interestingly, even when combined with autonomy support, controlling behaviors don’t produce any positive effects (Haerens et al. 2018). This challenges the idea that simply increasing motivation is always beneficial, highlighting why the type of motivation matters so much.

Why might this be the case? Different motivation styles trigger different physical responses in the body. When a controlling approach is used, cortisol levels—the body’s stress hormone—tend to rise, while an autonomy supportive style can lower them (Reeve and Tseng 2011). Even brain activity changes depending on how information is presented. When clients receive information in a controlling manner, it activates different areas of the brain compared to when the same information is shared in an autonomy supportive and personally relevant way (Zougkou et al. 2017). Thus, by adopting a more autonomy supportive approach, financial planners can work with a client’s natural physiology, rather than against it.

There are many techniques believed to support autonomy. To better understand and organize these methods, Teixeira et al. (2020) conducted a comprehensive review of past SDT interventions in the medical field. As part of this process, 18 leading SDT experts used a seven-step process to evaluate and classify the techniques based on how well they addressed a specific need or motivation, as well as their uniqueness and importance. This resulted in the following seven techniques: (1) eliciting client perspectives, (2) identifying external pressures, (3) using non-controlling language, (4) exploring aspirations and values, (5) providing meaningful rationales, (6) offering choices, and (7) encouraging experimentation and self-initiated behavior (Teixeira et al. 2020).

Putting the Techniques into Practice: Motivational Interviewing

Ideally, financial planners would have access to training programs that teach the autonomy supportive techniques identified by Teixeira et al. (2020), tailored specifically to financial planning. However, to our knowledge, no such curriculum currently exists. As a practical alternative, we highlight motivational interviewing (MI) as a way for financial planners to integrate autonomy support into client interactions. In the following sections, we’ll explore each technique, its connection to SDT, related concepts from Miller and Rollnick’s (2023) seminal work on MI, and practical examples of how financial planners can apply them.

Eliciting Client Perspectives on Condition or Behavior

The rationale behind this technique is that financial planners and clients may not see eye to eye on what constitutes a problem. Take, for example, a client spending $15,000 per month in pre-retirement, while their retirement projections show a spending capacity of only $8,000 per month. If the financial planner pushes the client to save more, it may come across as controlling. In MI, the instinct to immediately offer solutions is known as the “fixing reflex”—something MI specifically cautions against. An autonomy supportive approach would involve the financial planner briefly highlighting the income and expense discrepancy, then asking, “What do you make of that?” If the client shows concern over their low savings rate, they’re more likely to take ownership of it and find their own reasons to adjust their spending. This process fosters autonomous motivation.

Use Non-Controlling Information Language

Using informational rather than directive language can help the financial planner avoid creating external pressure (which can lead to external motivation) or internal pressure (which can lead to introjected motivation) for the client. In the earlier example, the financial planner might say: “My projections show that you should be able to spend $8,000 per month in retirement, compared to your current expenses of $15,000 per month.” This statement is clear and objective, without adding judgment or implying shame. MI encourages this kind of non-controlling, non-judgmental language because it respects the client’s autonomy, allowing them to process the information in a way that aligns with their values and goals. In MI, providing information typically comes only after spending ample time understanding the client’s perspective and is offered after asking permission—unless the client requests ideas or advice. This approach ensures that the information is relevant, welcomed, and supports the client’s autonomous decision-making.

Prompt Identification of Sources of Pressure for Change

Autonomy supportive financial advising involves recognizing when a client’s motivation is controlled rather than autonomous. For example, clients may say they want to retire, but their motivation may be driven by spousal pressure. Without exploring the underlying reasons, the financial planner risks reinforcing this controlled motivation. MI encourages financial planners to gently guess the source of the client’s motivation (i.e., a complex reflection). Doing so creates space for the client to clarify, reflect on their situation, and potentially shift toward more self-directed decision-making.

Explore Life Aspirations and Values

In SDT, values and aspirations are powerful drivers of autonomous motivation. When financial planners understand what truly matters to the client, they can help them evaluate whether decisions align with their long-term goals and values. For example, a client who values adventure might express this through a passion for traveling and exploring the world. If they are considering purchasing a new home that would limit their financial ability to travel, the financial planner can help them think through how that decision might affect their adventurous lifestyle.

MI complements this approach by helping clients articulate their values in a personally meaningful and self-directed way. Instead of using structured exercises like worksheets to identify values, MI uses reflections, affirmations, summaries, and open-ended questions to uncover what truly matters. In the home-buying example, the financial planner might ask, “How do you think buying this house could affect your ability to travel and live out your value of adventure?” This allows the client to explore the impact in their own words, rather than the planner stating it for them. By letting values surface naturally in conversation, this approach supports autonomous motivation and reinforces the client’s sense of ownership over their financial choices.

Importantly, the CFP Board identifies values as a form of qualitative data to gather in the first step of the financial planning process—understanding the client’s personal and financial circumstances (CFP Board of Standards 2022). MI can enhance this process by deepening discussions around values without imposing an external perspective. However, MI should supplement, not replace, the broader fact-finding process necessary for comprehensive financial planning.

Provide a Meaningful Rationale

Helping clients articulate their own meaningful reasons for pursuing a course of action can reinforce their sense of ownership and strengthen autonomous motivation. When giving advice, financial planners can support this by framing recommendations in ways that resonate with what matters most to the client. In contrast, generic rationales, such as “This strategy will help you make more money,” may undermine autonomous motivation (Vansteenkiste et al. 2009). MI encourages financial planners to resist the urge to “fix” and instead focus on drawing out the client’s motivations.

Provide Choice

Providing choice is about collaboratively exploring options rather than prescribing a solution. For example, a client concerned about job security due to industry changes may want to achieve financial independence quickly but also desire a new luxury car. Recognizing the potential conflict between these goals, a financial planner can present different scenarios—such as their current retirement date and Monte Carlo score with no car purchase—alongside alternatives, like delaying retirement to maintain the same Monte Carlo score while still buying the car. MI reinforces this process by equipping planners with skills to develop these alternatives with the client rather than for them. This collaborative approach deepens engagement and nurtures autonomous motivation, ensuring clients feel in control of their financial decisions.

Encourage Experimentation and Self-Initiating Behavior

Another way to support a client’s autonomy is by encouraging experimentation and self-initiated behavior, allowing clients to explore financial strategies in natural and enjoyable ways (Teixeira et al. 2020). MI shares this emphasis on autonomy by guiding clients to discover their own motivations for change. Rather than prescribing solutions, MI helps clients connect financial behaviors to their interests, making new habits feel less like obligations and more like meaningful choices. When clients engage in personally rewarding behaviors, they’re more likely to sustain them.

For example, a client who values social connections but struggles with overspending on dining out might enjoy experimenting with hosting themed dinner parties at home. With permission to offer a suggestion, the financial planner could frame this as a way to maintain their social life while spending less—an approach that feels enjoyable rather than restrictive. The financial planner can then follow up by asking, “How does that idea sound to you?” This approach follows MI’s “ask-offer-ask” method, which involves requesting permission before and checking in after offering advice. By helping clients align financial behaviors with what they naturally enjoy, planners can foster intrinsic motivation and long-lasting change.

Teaching MI to Financial Planners

As of 2022, over 1,900 controlled clinical trials involving MI have been conducted in various disciplines, such as healthcare and mental health (Miller 2023), validating MI as an effective tool for driving positive behavior change (Miller and Rollnick 2023). MI is a person-centered communication technique for strengthening a client’s own motivation for change and commitment (Miller and Rollnick 2023) and provides a practical way for financial planners to become more autonomy supportive. Supporting a client’s autonomy is, in fact, a defining characteristic of an MI conversation (Miller and Rollnick 2023). Financial planners can build a foundation in MI by attending beginner training, typically a two-day workshop, available through the Motivational Interviewing Network of Trainers (MINT) website.1

To support financial planners in mastering MI, Lynn (2025) developed the financial planning emotional intelligence (FPEQ) scorecard, a practical tool designed to develop these techniques in practice. The scorecard outlines core MI communication skills, including:

- Open-ended questions, affirmations, reflections, and summaries (OARS).

- Resisting the fixing reflex (i.e., refraining from giving unsolicited advice).

- Prioritizing the client’s talking time and using intentional pauses.

- Avoiding financial jargon and encouraging a client-led agenda.

- Observing and responding to non-verbal cues.

The FPEQ scorecard transforms these principles into a measurable framework that financial planners can use to evaluate their own communication skills, provide constructive peer feedback for team members, and identify clear next steps for improvement.

Conclusion

For financial planners who want to truly help clients live their best lives, the outcome of financial planning must be measured not in dollars, but in a client’s own well-being and life satisfaction. The study of autonomy support illuminates how financial planners who use autonomy supportive techniques can positively influence client interactions and support their well-being outcomes. The clients of financial planners who authentically embrace these practices and techniques are in for a rare treat in a fast-paced and often transactional world.

Read Next

“Training Advisers to Build Superior Client Relationships with Motivational Interviewing and the FPEQ Scorecard,” Christina Lynn, February 2025

Endnote

- Visit https://motivationalinterviewing.org/calendar to find trainings.

References

Asebedo, S. D. 2019. “Financial Planning Client Interaction Theory (FPCIT).” Journal of Personal Finance 18 (1): 9–23.

CFP Board of Standards. 2022. Guide to the 7-Step Financial Planning Process: A Case Study Illustration for Solo Practitioners. www.cfp.net/-/media/files/cfp-board/standards-and-ethics/compliance-resources/guide-to-financial-planning-process.pdf.

Di Domenico, S. I., R. M. Ryan, E. L. Bradshaw, and J. J. Duineveld. 2022. “Motivations for Personal Financial Management: A Self-Determination Theory Perspective.” Frontiers in Psychology 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.977818.

Haerens, L., M. Vansteenkiste, A. De Meester, J. Delrue, I. Tallir, G. Vande Broek, et al. 2018. “Different Combinations of Perceived Autonomy Support and Control: Identifying the Most Optimal Motivating Style.” Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy 23 (1): 16–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2017.1346070.

Howard, J. L., J. S. Bureau, F. Guay, J. X. Y. Chong, and R. M. Ryan. 2021. “Student Motivation and Associated Outcomes: A Meta-Analysis from Self-Determination Theory.” Perspectives on Psychological Science 16 (6): 1300–1323. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691620966789.

Lynn, C. 2025. “Training Advisers to Build Superior Client Relationships with Motivational Interviewing and the FPEQ Scorecard.” Journal of Financial Planning 38 (2): 42–49.

Miller, W. R. 2023. “The Evolution of Motivational Interviewing.” Behavioral and Cognitive Psychotherapy 51 (6): 616–632. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465822000431.

Miller, W. R., and S. Rollnick. 2023. Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change and Grow. 4th ed. The Guilford Press.

Reeve, J., and C. M. Tseng. 2011. “Cortisol Reactivity to a Teacher’s Motivating Style: The Biology of Being Controlled Versus Supporting Autonomy.” Motivation and Emotion 35 (1): 63–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-011-9204-2.

Ryan, R. M. 2023. “The Oxford Handbook of Self-Determination Theory.” In Oxford Handbook of Self-Determination Theory. Edited by R. M. Ryan. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780197600047.001.0001.

Ryan, R. M., and E. L. Deci. 2000. “Self-Determination Theory and the Facilitation of Intrinsic Motivation, Social Development, and Well-Being.” American Psychologist 55 (1): 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68.

Ryan, R. M., and E. L. Deci. 2017. Self-Determination Theory: Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development, and Wellness. Guilford Publications.

Teixeira, P. J., M. M. Marques, M. N. Silva, J. Brunet, J. L. Duda, L. Haerens, et al. 2020. “A Classification of Motivation and Behavior Change Techniques Used in Self-Determination Theory-Based Interventions in Health Contexts.” Motivation Science 6 (4): 438–455. https://doi.org/10.1037/mot0000172.

Van den Broeck, A., J. L. Howard, Y. Van Vaerenbergh, H. Leroy, and M. Gagné. 2021. “Beyond Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation: A Meta-Analysis on Self-Determination Theory’s Multidimensional Conceptualization of Work Motivation.” Organizational Psychology Review 11 (3): 240–273. https://doi.org/10.1177/20413866211006173.

Vansteenkiste, M., B. Soenens, J. Verstuyf, and W. Lens. 2009. “‘What Is the Usefulness of Your Schoolwork?’: The Differential Effects of Intrinsic and Extrinsic Goal Framing on Optimal Learning.” Theory and Research in Education 7 (2): 155–163. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477878509104320.

Zougkou, K., N. Weinstein, and S. Paulmann. 2017. “ERP Correlates of Motivating Voices: Quality of Motivation and Time-Course Matters.” Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience 12 (10): 1687–1700. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsx064.