Journal of Financial Planning: July 2025

NOTE: Please be aware that the audio version, created with Amazon Polly, may contain mispronunciations.

Executive Summary

- Survey data from 1,303 U.S. adults found that the vocabulary used to describe life after career is limited to a relatively small number, and is overwhelmingly positive or neutral, focusing on broader concepts and aspirations rather than specific objects or activities.

- Although retirement is a dynamic and individualized phase rather than a fixed milestone, data showed a high consistency in vocabulary people use to describe life after career.

- People may have difficulty clearly imagining and articulating their future life, which points to the need for financial professionals to engage clients in conversations to help envision what retirement may look like for them.

- While generation and gender differences were minimal, younger generations focused more on success and career-related goals, whereas older generations emphasized health, social connections, and leisure, reflecting their stage of life and priorities.

- Sentiment analysis showed optimism across most groups, but revealed that poorer self-rated health, loneliness, perceived disconnectedness to future self, less technology experience, and financial insecurity correlate with negative views of retirement, underscoring the need for new conversations.

- Retirement vocabulary provides a starting point for meaningful discussions between financial professionals and clients, guiding toward a complete understanding of clients’ relevant behavioral characteristics, with an aim to help explore individual goals and address both aspirations and challenges for comprehensive retirement planning.

Dr. Joseph Coughlin (email HERE) is founder and director of the MIT AgeLab, where his work explores how global demographics, technology, and changing behaviors are transforming business and society. He received his Ph.D. in political science from Boston University.

Dr. Chaiwoo Lee (email HERE) is a research scientist at the MIT AgeLab, where she studies how people across generations accept, use, and interact with new technologies. She received her B.S. and M.S. in industrial engineering from Seoul National University and received a Ph.D. in engineering systems from MIT.

Sophia Ashebir (email HERE) is a graduate research assistant at the MIT AgeLab, where she is involved in research related to caregiving, vaccines and preventive health, and long-term care. She received her B.A. in economics and comparative race and ethnicity from Wellesley College and is pursuing her master’s degree in city planning at MIT.

Dr. Lisa D’Ambrosio (email HERE) is a research scientist at the MIT AgeLab. Her research includes work on longevity preparedness; caregiving; well-being, social isolation, and loneliness; transportation and mobility; and technology use and adoption. Her Ph.D. is from the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and her A.B. is from Brown University.

Katie Warren (email HERE) is a technical associate at the MIT AgeLab where she is involved in research on financial planning and attitudes toward longevity. She received her M.S. in data science from Tufts University and her B.S. in mathematics and political science from Northeastern University.

Acknowledgment: The Massachusetts Institute of Technology AgeLab gratefully acknowledges MassMutual for supporting this research.

Click HERE to read this article in the DIGITAL EDITION.

NOTE: Click on the images below for PDF versions.

JOIN THE DISCUSSION: Discuss this article with fellow FPA Members through FPA's Knowledge Circles.

FEEDBACK: If you have any questions or comments on this article, please contact the editor HERE.

Scientific, technological, medical, and health developments over the past 125 years have resulted in unprecedented gains in lifespan as people on average live longer than ever before (Coughlin 2017). As a result, the population of older adults in the United States—typically defined as people age 65 or older—has increased overall and relative to the population as a whole. This particularly rapid growth is fueled largely by the aging of the baby boomer generation, who began turning 65 in 2011 and who will all be age 65 by 2030 (Caplan 2023). Although the growth rate of the older population is expected to slow as the baby boomers turn 65, the overall population of older adults is nevertheless projected to continue to grow: from a projected 71.18 million (20.6 percent of the population) in 2030 to 82.13 million (22.8 percent of the population) in 2050 (calculated from U.S. Census 2023).

While these data underscore the significant, broadscale demographic shifts happening in the United States (and indeed across the world (Bloom and Zucker 2023)), people experience these changes at the individual level as well: these added years of lifespan mean that people are spending an average of seven years longer in what have traditionally been considered their retirement years (Coughlin 2017). The U.S. Centers for Disease Control estimate that a 65-year-old man could expect to live an additional 17.5 years, and a 65-year-old woman, 20.2 years (Kochanek et al. 2024). Thus, people who reach the age of 65 might expect to have, on average, some 17 to 20 years ahead of them in this traditional retirement period—about a third of their adult lives (Coughlin 2019).

With a growing, aging population comes new ideas about how people want to live and what they want to do in older age—including whether they actually want or can afford to “retire” from the workforce. Longer life expectancies may mean that retirement might no longer be simply a singular moment but instead a “process that varies in its timing and duration”—where people might un-retire and re-retire (Marshall et al. 2001; Kojola and Moen 2016). Longevity may also provide the time for people to develop or plan for different kinds of goals, activities, or opportunities that they want to pursue in later life or after the conclusion of a primary career. Later life for many now constitutes an entirely new phase of life, for which we are still developing new vocabulary, new expectations, and new celebrations.

The goal of this research is to dive into people’s vision for their later lives by investigating the vocabulary of retirement. Regardless of whether someone is a part of the growing share of people who indicate that they do not ever plan to retire from work, or among the majority of people who would like to and do plan to retire, understanding what people want and hope for in their later lives is key in order for them to be able to plan effectively for it (Brown 2023).

While much of existing research on retirement focuses on financial planning perspectives, there is less work around people’s perceptions of retirement itself and the particular language they use to capture this increasingly complex time of life. Furthermore, limited discussion exists around how this language may vary by demographic characteristics or how it may have changed over time. In this work we investigate the words and language that people use when they think about their lives after career—in short, their retirement—and how this language may have changed, if at all, with the continued aging of the population and in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, which was associated with a number of younger people reconceptualizing the role of savings and work in their future (Cowles 2021; Khan and Pandey 2023).

Literature Review

Despite longer lifespans and health spans, 73 percent of non-retirees ages 30 and older in the United States report that they expect to retire at some point (Brown 2023). There is a good deal of research on retirement focused on people’s and households’ financial preparation and planning (Frydman and Camerer 2016; Yin et al. 2024), but the work around planning for the multiple dimensions of later life, e.g., health, social connectedness, and mobility (Coughlin 2019; Liu et al. 2022), is more limited, as is work around people’s perceptions of retirement itself. And as people live longer, healthier lives, the meaning of retirement—and relatedly the financial resources needed for this time of life—may also be evolving. Supporting more effective and engaged planning for this evolving and emerging period requires a better understanding of what people themselves think about this time, what they might hope or expect from it, and how they envision their future selves and lives (Bačová et al. 2024; Hershfield et al. 2025; Oyserman and Horowitz 2023).

One means to explore what people think about their future is to explore their conceptions of their possible selves. As Markus and Nurius (1986) describe them, possible selves:

include representations of the self in the future . . . . Possible future selves, for example, are not just any set of imagined roles or states of being. Instead they represent specific, individually significant hopes, fears, and fantasies . . . . These possible selves are individualized or personalized, but they are also distinctly social. Many of these possible selves are the direct result of previous social comparisons in which the individual’s own thoughts, feelings, characteristics, and behaviors have been contrasted to those of salient others . . . . An individual is free to create any variety of possible selves, yet the pool of possible selves derives from the categories made salient by the individual’s particular sociocultural and historical context and from the models, images, and symbols provided by the media and by the individual’s immediate social experiences (954).

Thus, people hold cognitive representations of their imagined future selves, which might include both positive and negative futures, and these representations are shaped both by individual experiences as well as by the larger social discourse. In the context of thinking about one’s life after career—traditionally retirement years—people’s notions of their future possible selves might then be shaped by, for example, comparisons with how other family members experienced life after career, and a desire to emulate that or not (e.g., hoping for a more active, engaged retirement period for oneself than a parent currently has), but such conceptions are likely also influenced by how this period of life is presented and discussed in the wider cultural conversation.

Some research has explored people’s conceptions of their future selves in older adulthood. For example, Anderson and Gettings (2019) collected qualitative data and drawings from members of the millennial and Gen Z generations. They found that among these younger generations, age/aging and retirement were largely considered distinct concepts. Aging was associated with negative stereotypes, language, and imagery, notably around physical decline; in contrast, retirement was viewed more positively, as a period of reward or leisure, with images signaling relaxation and financial success. Hershfield with colleagues has led a multi-year research program to understand better how people’s connections to their future selves—how much they relate to and identify with who they are in the future—affects choices people make in the present (Hershfield 2023; Hershfield et al. 2025). For example, people who were literally better able to envision themselves as older adults—via a computer-aged visual of themselves—were more likely to save for retirement in the present (Hershfield et al. 2011).

Lee and Coughlin (2018) used a national U.S. sample of people ages 18 and older to investigate their conceptions of “life upon completion of career”—choosing this phrase rather than “retirement” to try to avoid cuing people to think of particular words or images culturally associated with retirement. In soliciting people’s top words and images, their approach provides a snapshot of the kinds of language and concepts that people have available and accessible when they think about their future, older selves (Zaller and Feldman 1992). This study found that people’s accessible information for this period of their future lives relied on a relatively limited vocabulary, with 27 words capturing over half of individual word responses. Words skewed positively, and the vast majority of the sample provided at least one positive word. They also found that older respondents were more likely to give words that focused on social connections (e.g., friends) or actions (e.g., travel, hobbies), and younger more likely to offer broader words (e.g., great, cool); men were more likely to note words that indicated freedom from responsibilities (e.g., relax), and women more likely to offer words more closely tied to achievement (e.g., fulfilled, success).

Other research has explored the broader social and cultural conversations around retirement and older adulthood. For example, Gettings (2018) explored how four mainstream U.S. media outlets represented retirement between 2009 and 2015 and identified three primary themes from the content. The first was retirement financing, focused on people’s need and responsibility to save and plan financially for retirement. The second was labeled as “charting a ‘new’ retirement course,” comprising three elements: retirement as unique and different for the baby boomers relative to earlier generations; the need for and use of advice professionals, including not only financial advisers but also people like life coaches; and retirement representing the opportunity to make an active choice around where to live. The third theme uncovered was around encouraging people to stay active in retirement. In short, retirement was presented as something new and different for the baby boomers—distinctively more active than for previous generations, but also a period of life in which people could benefit from financial advice.

Because people’s language and their conceptions of their future selves are related to their abilities to plan (Hershfield et al. 2011), in this paper we adopt the study approach in Lee and Coughlin (2018) with a focus on language to investigate how people’s accessible vocabulary around later life may have shifted post-COVID-19 as more baby boomers and older members of Gen X enter a retirement phase of life and as the newest generation of U.S. adults, Gen Z, enters adulthood.

Methodology

The design of this study draws on Lee and Coughlin’s (2018) research. An online survey was fielded to a national sample age 18 and older living in the United States from Qualtrics Panels between February 2024 and May 2024. To capture the vocabulary that people had available, participants were asked to: “List 5 words that come to your mind when you think about life upon completion of your career.” The word “retirement” was not included in the question phrasing, as it may have led people to focus on how retirement is conceptualized in the culture more broadly, rather than focusing on what they envisioned for themselves at the end of their careers.

The questionnaire also captured data related to people’s: (1) self-assessed retirement readiness; (2) perceived closeness to future self; (3) self-rated health and loneliness (the Three-Item Short Form revised from the UCLA Loneliness Scale, Hughes et al. 2004); and (4) technology experience and attitudes. Participant demographic data were also collected.

A total of 1,303 participants completed the survey. The sample was stratified by generation (as defined in Dimock 2019) and gender to ensure that there were sufficient cases for comparison across these groups. Table 1 displays demographic characteristics for the sample.

Results: The Vocabulary of Retirement

Small and Positive Vocabulary

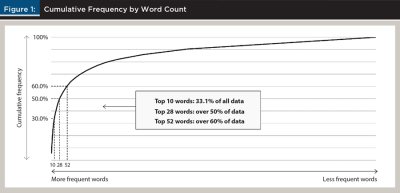

The survey sample generated 6,515 individual word responses to the prompt “life upon completion of your career.” Of these, only 1,074 represented unique words. Relatively few accounted for a majority of the responses: the top 10 most frequently used words covered about a third of all word responses, and the 28 most frequently used for about 50 percent of all the responses (see Figure 1). Given that the average American is estimated to have a vocabulary size of over 40,000 words (Brysbaert et al. 2016), only a small percentage is being used to describe a growing period of people’s lives. One possible explanation for this is that there is a high degree of consensus around what is top of mind for people when they think about their life after career. A significant portion of the vocabulary may also be due to what people see in public media, rather than what they are able to imagine for themselves.

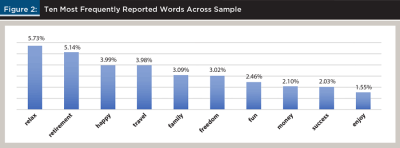

Figure 2 displays the top 10 most frequently reported words to describe life after career for the whole sample. The list was topped by “relax” followed by “retirement,” both being reported by more than 5 percent of the sample. These top words tended to be ones that were positive rather than negative, and most reflected broader concepts, while words corresponding with specific objects, notions, or activities rarely made the top 10.

For the overall sample, the top 10 words could be grouped into three constructs. The first is “positive realizations,” which is a set of words that includes “relax,” “retirement,” “happy,” “fun,” “enjoy,” “freedom,” and “success.” “Travel” also belongs with this group, as it likely captures people’s aspirational hopes and plans for their time in life after career, when they have sufficient time to visit the places they want to go. The word “retirement” itself was the second-most mentioned word in the overall sample, reflecting the extent to which this term is associated with the phase and time of life when one’s career has concluded. The second construct captured by the top words is “relationships” represented by the word “family,” and the third is “money”—which was the only word that specifically referred to finances or financial planning among the top words to describe life after career.

Patterns by Generation and Gender

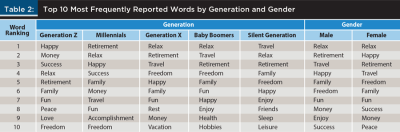

Table 2 displays the top 10 words people reported to describe life after career by generation and by gender. There were some differences within each generation from the top 10 words for the whole of the sample. “Relax,” “retirement,” and “travel” were the top three mentioned words among Gen X, baby boomers, and the Silent Generation, and “retirement” and “relax” were in the top three for millennials, along with “happy” as their third most frequent word. Gen Z reported “happy” as their most frequent mention, followed by “money” and “success.”

Among the youngest generation, Gen Z, “peace” and “love” surfaced as unique top 10 words; among millennials, “accomplishment” was unique. These words are aligned with the concept of positive realizations in retirement, although “love” might also fit with “relationships.” “Success” is also among the top 10 words for Gen Z and millennials, but it does not appear in the top 10 for any of the other generations.

Among Gen X, “rest” and “vacation” were unique, and “health” and “hobbies” were among the top 10 mentioned by baby boomers. For Gen X, the theme of a break seems to be stronger with these top 10 mentions, as well as the aspirations around vacation that are similar to those of travel. For baby boomers, who are more likely to be closer to or in retirement, the words may signal a sense of what is important to enjoying retirement: notably, “health” (in order to be able to do what one wanted and hoped to do in retirement) and “hobbies” (as a pleasurable means to spend time in retirement) emerged. Finally, among the oldest, the Silent Generation, “friends,” “sleep,” and “leisure” were unique. “Friends” is consistent with the “relationships” construct that includes “family,” but “sleep” and “leisure” are more aligned with the positive realization, even if they seem to suggest more of a passive enjoyment rather than active (e.g., as “travel” might).

The top 10 words by gender did not vary as much as they did by generation. The only different word among the top 10 was that men had “enjoy” whereas women had “peace.” Few minor differences were observed between men and women in where the words ranked. For instance, “happy,” “freedom,” and “success” ranked higher among women, while “retirement,” “family,” and “money” ranked slightly higher among men.

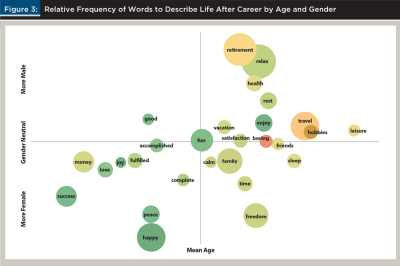

While even by generation and gender many people reported similar words—resulting in a relatively high degree of similarity in people’s top mentions of life after career—an analysis of more frequent word mentions by generation and gender was undertaken. This looked beyond simply the top mentions to include the 28 words that covered 50 percent of all responses in order to explore what other differences might emerge. The results of this analysis are in Figure 3, which displays the words that people were more likely to report based upon their age and gender. Larger bubbles indicate words that people across the sample used more often (e.g., the top 10 word mentions such as “relax” and “retirement”); smaller bubbles indicate less frequently mentioned words (e.g., such as “joy”, mentioned by 2.8 percent of the sample). Green bubbles indicate more positive words, yellow more neutral ones, and red more negative words.

From Figure 3, the word “fun” is placed near the center, indicating that the average age of those who chose “fun” to describe life after career was close to the average age of the total sample, and that similar proportions of men and women provided this word. The chart also shows, however, some notable demographic differences. Fewer unique words were associated with being younger and male, and women were more likely to choose neutral words. Younger women were more likely than others to use “success,” “peace,” and “fulfilled.” Among the top 28 most popular words, younger men used “good” more than others. Older women used “time,” “sleep,” and “freedom” at a higher proportion than other groups, and “health” and “leisure” were more popular among older men than others. Younger respondents were also more likely to use terminology related to work and career (e.g., “success,” “accomplishment,” “work,” “money”) as well as more generic emotion-based terms (e.g., “good”). In contrast, older respondents were more likely to offer words reflecting leisurely pursuit and social connectedness (e.g., “friends,” “travel,” “hobbies”).

General Sentiment Analysis—Positive, Neutral, and Negative Words

Each case was coded in terms of the overall sentiment represented in the words that they provided—whether they had a positive, negative, and/or neutral tone. This generally followed categorization used in previous studies (Raue et al. 2017; Lee and Coughlin 2018) where a response was coded as positive, negative, and/or neutral if one or more included words had the corresponding sentiment and assigned multiple sentiments if it included words of different sentiments. This study used the RoBERTa (Robustly optimized BERT) approach, which builds on the previous BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers) language representation model, to assign sentiment values to individual words with improved data pre-training techniques (Liu et al. 2019). RoBERTa, like BERT, is a widely used model for sentiment representation in natural language processing. It provides a probability distribution for each word or phrase, indicating the likelihood of it having a negative, neutral, or positive sentiment based on the context in which it appears (Horev 2018). Since RoBERTa is pre-trained on a large corpus of text and designed to understand context, it is intended to capture nuanced meanings of words. Words that appear in both positive and negative contexts may be assigned a neutral sentiment label, reflecting their context-dependent nature. This resulted in many words receiving neutral sentiment scores. To ensure a more balanced distribution of sentiment labels, any word with a positive or negative sentiment score greater than 0.3 was assigned the corresponding label.

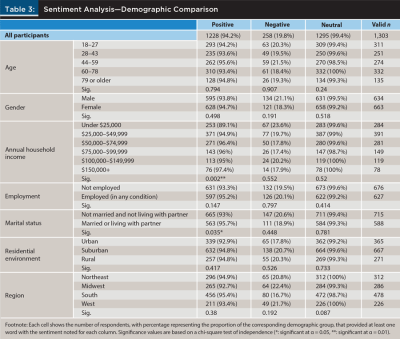

Results of coding, as shown in Table 3, showed that perceptions of life after career were far more positive than negative. Among the 1,303 total cases, 1,228 included one or more positive words, while only 258 included one or more negative words. This positive tone was observed across various demographic and socioeconomic segments. Participants of all ages provided overwhelmingly positive responses, and the sense of optimism was shared between men and women. No significant differences were found in terms of the overall sentiment between employed and unemployed individuals, as well as between people in different geographic regions or residential environments. Household income and marital status showed a notable association with whether an individual provided positive descriptions for life after career. People reporting household income at the lowest level (under $25,000 annually) were significantly less likely to provide words with a positive tone compared to higher income groups, and individuals who were married or living with a partner were significantly more likely to show a positive tone in their responses.

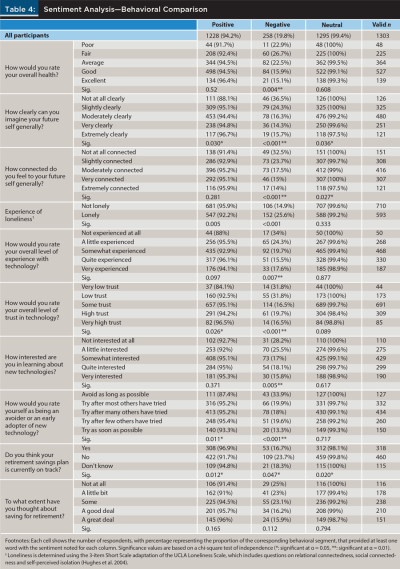

Differences in sentiments around life after career, however, were more evident among individuals of various behavioral characteristics and backgrounds, as summarized in Table 4. For instance, people who rated their overall health as below average were significantly more likely to provide a negative word compared to those who rated their health as good or excellent. People’s perceived closeness to their future self also had significant associations with the affect of the words they provided. Being able to more clearly imagine one’s future self showed a positive association with higher likelihood of providing positive words. In contrast, people with a less clear vision of their future self and those who felt less connected to their future self were far more likely to provide negative words. Current experiences of social isolation and loneliness also showed strong associations with people’s future outlook, with those who reported frequently feeling isolation, lack of companionship, and social exclusion being significantly more likely to provide negative words while being less likely to provide positive words.

Experiences and attitudes regarding new technologies also had significant associations with people’s sentiments around life after career. In general, individuals with higher levels of openness to technology—including being more experienced with technology, having higher trust and interest in technology, and being willing to adopt new technologies—were less likely than their counterparts to enter negative words. Current self-rated financial readiness also had significant ties with people’s future outlook, with those saying that their retirement savings is currently on track being more likely to provide positive words and less likely to enter negative words compared to people who either did not feel that their retirement savings plan was on track and those who were not sure. Consideration around saving for retirement also reflected this trend, where people who had thought more about the topic were more likely to provide positive words while being less likely to enter negative words, but these associations were not statistically significant.

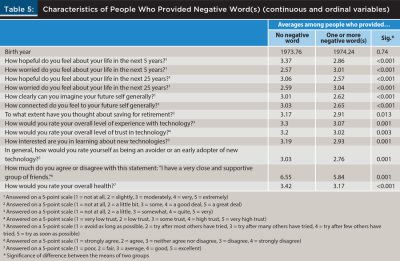

Characteristics of Individuals with Negative Outlook

While a large majority of people provided positive and neutral words to describe their perspectives regarding life after career, only a small proportion used one or more negative words. Additional analysis looked into characteristics of those who provided negative words to better understand current demographic and behavioral situations that may be associated with a more pessimistic future outlook.

As shown in Tables 5 and 6, people who gave one or more negative words in their responses tended to have the following characteristics: less hopeful and more worried about their life in the future; less likely to be able to clearly imagine their future self; feeling less connected to their future self; less experienced, interested in, or trusting of new technology; less likely to be socially connected; less likely to feel healthy; thought less about saving for retirement; and less likely to feel confident about their retirement savings plan. While these behavioral and attitudinal characteristics showed significant relationships with people’s tendency to describe their post-career lives negatively, basic demographic and socioeconomic variables such as age, gender, household income, employment, education, marital status, and residential environment did not show any significant associations.

Conclusion and Discussions

This study explored how individuals imagine and describe life in retirement by asking them about the top words that came to mind when they were asked to describe their life upon completion of career. The results from a survey of 1,303 adults in the United States revealed that people’s available vocabulary around life after career displayed a high degree of consistency, with the 10 most frequent words capturing a third of all responses, and only 28 words covering half of all data reported. This shows a great deal of consensus around a small number of words to describe a growing period of time in people’s lives, but also suggests that people have difficulty picturing and articulating their future life.

This limitation in people’s ability to imagine their life after career in detail aligns with findings in the previous study by Lee and Coughlin (2018), which used a similar approach to describe and understand how people imagine and picture their retirement. Also consistent with results in Lee and Coughlin (2018) is the general positivity in the vocabulary chosen to describe future outlook. While a direct comparison isn’t applicable due to differences in methods used for sentiment coding, the similarity may be an indication that optimism is still prevalent, after the nine-year gap in data collection and experience of the COVID-19 pandemic, among many individuals across various demographic groups.

Two limitations of this study stem from the nature of the survey sample and the approach to collect a few words to capture people’s conceptions of life after retirement. The collection of survey data was entirely based on an online sample, which may not fully represent the demographic, socioeconomic, and behavioral characteristics of the national population, some of whom do not have regular internet access. Additionally, the survey format did not allow for an in-depth analysis into the reasoning behind people’s selection of words. A qualitative approach utilizing interviews or focus groups may meaningfully expand our understanding of the topic with added narratives and explanations. Future research could build on this work by leveraging a broader participant base inclusive of those currently not online to uncover perceptions and behaviors potentially not captured in this study, and by a research design that would enable people to describe in greater detail how their retirement words fit into their broader visions or conceptions of their lives after career.

Implications for Practice

Findings suggest several practical implications for financial professionals who are working to help clients envision their retirement and plan according to their aspirations.

The vocabulary that is top of mind for people to describe life after career changes with age. The vocabulary that is more distinctive about life after career may reflect their more current concerns or what they wish for. For example, younger people, who are at the start of their careers were more likely to use words related to work, whereas older people who are more likely to have completed or to be near the end of their careers focus more on words associated with personal relationships and social connections. One possible implication is that in communicating planning strategies and in motivating people to plan better, financial professionals could focus on goals and wishes that are more distinctive and different across ages and between genders. For example, advisers might link retirement planning with successful career development for younger adults, and with enabling social engagement and pursuing personal interests/hobbies/time for self for older adults.

In general, the vocabulary of retirement trends positively, although the reality of retirement may not always be. Across generations and other consumer segments, popular words illustrated hopes for opportunities around travel, hobbies, and enjoyment, as well as time with family and loved ones. However, aging for some may involve challenges as health changes. Financial professionals can play a crucial role as educators, raising and addressing less enjoyable but important topics that need clients’ consideration. These include, for example, potential long-term care needs, caregiving responsibilities, changes in personal mobility affecting community engagement, and retiring from driving. Discussing these very real issues and making plans to ensure that individuals’ wishes are met, rather than being unprepared should they arise, means that clients can enjoy their time after career all the more. Clients can be confident that they have planned to take the paths they would prefer and to protect themselves and their loved ones in the face of potential future needs.

While the sentiment analysis showed an overwhelmingly positive outlook in general, a more detailed comparison across consumers of different backgrounds and characteristics showed some significant associations between behavioral characteristics and a tendency to have a relatively negative perspective. Higher likelihoods of entering negative words were observed among individuals with worse self-rated health, higher self-assessed loneliness, less experience and interest regarding new technologies, less ability to imagine or feel connected with future self, and less confident about their retirement savings plan. A deeper look into the minority subset of people who provided negative words to describe their life after career revealed that they tended to be less hopeful and more worried about their future, and they thought less about retirement. Interestingly, basic demographics and socioeconomic status such as age, gender, income, education, marital status, and residential environments did not have significant associations with the sentiments represented by the words, with an exception of positive sentiment being significantly tied with having income higher than $25,000 and being married or living with a partner. While most demographic and socioeconomic characteristics are easy to observe, ask about, and keep a record of, the more influential behavioral characteristics such as experience of loneliness and connectedness with future self will likely require additional conversations that go beyond topics commonly covered during meeting between financial professionals and clients.

Overall, this study suggests that the vocabulary of retirement is not the end point—it is a starting point for conversations. The results from this research can serve as a guide to understanding how consumers of different backgrounds, characteristics, and experiences perceive life after their careers. But asking anyone what words come to mind when they think about their life upon completion of career yields just that—a list of words. Financial professionals can use the words from the study—or ones that their clients provide in answer to the question of what their own top words are—as a starting point for conversations. These conversations are an opportunity to ask clients why they chose a given word and what it means to them. They are openings to explore with clients what their priorities are for their later lives, as well as to help couples or families have conversations about any collective planning for later life. Financial professionals can use the vocabulary of retirement over time with clients as well, as they move through different stages of life and new priorities and conversations emerge.

Citation

Coughlin, Joseph F., Chaiwoo Lee, Sophia Ashebir, Lisa D’Ambrosio, and Katie Warren. 2025. “Mapping the Language of Retirement: Aspirations, Challenges, and Planning Implications.” Journal of Financial Planning 38 (7): 50–67.

References

Anderson, Lindsey. B., and Patricia E. Gettings. 2019. “Examining Young Adults’ Expectations for Retirement: An Emerging Tension.” Communication Studies 71 (1): 59–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/10510974.2019.1691619.

Bačová, Viera, Michal Kohút, and Peter Halama. 2024. “Retirement Concepts as Predictors of Preretirement Consideration and Planning.” New Horizons in Adult Education and Human Resource Development 36 (4): 263–274. https://doi.org/10.1177/19394225241280099.

Bloom, David E., and Leo M. Zucker. 2023. “Aging is the Real Population Time Bomb.” Finance and Development Magazine. International Monetary Fund. www.imf.org/en/Publications/fandd/issues/Series/Analytical-Series/aging-is-the-real-population-bomb-bloom-zucker.

Brown, S. Kathi. 2023, July. “Envisioning Retirement Today—AARP Financial Security Trends Survey.” AARP Research. www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/research/topics/work-finances-retirement/financial-security-retirement/financial-security-trends-july-2023-retirement-spotlight.doi.10.26419-2Fres.00525.031.pdf.

Brysbaert, Marc, Michaël Stevens, Paweł Mandera, and Emmanuel Keuleers. 2016. “How Many Words Do We Know? Practical Estimates of Vocabulary Size Dependent on Word Definition, the Degree of Language Input and the Participant’s Age.” Frontiers in Psychology 7: 1116. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01116.

Caplan, Zoe. 2023. “U.S. Older Population Grew From 2010 to 2020 at Fastest Rate Since 1880 to 1890.” U.S. Census Bureau. www.census.gov/library/stories/2023/05/2020-census-united-states-older-population-grew.html.

Coughlin, Joseph F. 2017. The Longevity Economy: Unlocking the World’s Fastest-Growing, Most Misunderstood Market. New York, NY: PublicAffairs.

Coughlin, Joseph F. 2019. “Planning for 8,000 Days of Retirement: Advisor Value in Today’s Longevity Economy.” Investments & Wealth Monitor March/April. https://publications.investmentsandwealth.org/iwmonitor/library/item/march_april_2019/3715890/.

Coughlin, Joseph F. 2019, April 13. “Why 8,000 Is the Most Important Number for Your Retirement Plan.” Forbes. www.forbes.com/sites/josephcoughlin/2019/04/13/why-8000-is-the-most-important-number-for-your-retirement-plan/.

Cowles, Charlotte. 2021, July 14. “The Pandemic Forged New FIRE Followers, With a Difference.” New York Times. www.nytimes.com/2021/07/14/business/financial-independence-retire-early-fire-retirement-savings.html.

Dimock, Michael. 2019. “Defining Generations: Where Millennials End and Generation Z Begins.” Pew Research Center. www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2019/01/17/where-millennials-end-and-generation-z-begins/.

Frydman, Cary, and Colin F. Camerer. 2016. “The Psychology and Neuroscience of Financial Decision Making.” Trends in Cognitive Sciences 20 (9): 661–675. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2016.07.003.

Gettings, Patricia E. 2018. “Discourses of Retirement in the United States.” Work, Aging and Retirement 4 (4): 315–329. https://doi.org/10.1093/workar/way008.

Hershfield, Hal E. 2023. Your Future Self: How to Make Tomorrow Better Today. New York, NY: Little, Brown Spark.

Hershfield, Hal E., Craig I. Brimhall, and Susan Kerbel. 2025. “Exploring the Distribution and Correlates of Future Self-Continuity in a Large, Nationally Representative Sample.” Judgment and Decision Making 20 (e9): 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1017/jdm.2024.23.

Hershfield, Hal E., Daniel G. Goldstein, William F. Sharpe, Jesse Fox, Leo Yeykelis, Laura L. Carstensen, et al. 2011. “Increasing Saving Behavior through Age-Progressed Renderings of the Future Self.” Journal of Marketing Research 48 (SPL): S23–S37. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkr.48.SPL.S.

Horev, Rani. 2018. “Bert Explained: State of the Art Language Model for NLP.” Towards Data Science Archive. https://medium.com/towards-data-science/bert-explained-state-of-the-art-language-model-for-nlp-f8b21a9b6270.

Hughes, Mary E., Linda J. Waite, Louise C. Hawkley, and John T. Cacioppo. 2004. “A Short Scale for Measuring Loneliness in Large Surveys: Results from Two Population-Based Studies.” Research on Aging 26 (6): 655–672. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027504268574.

Khan, Abdul W., and Jatin Pandey. 2023. “Exploring Fire for Financial Independence Retire Early (FIRE): a Netnography Approach.” Journal of Consumer Marketing 40 (6): 775–784. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCM-07-2021-4788.

Kochanek, Kenneth D., Sherry L. Murphy, Jiaquan Xu, and Elizabeth Arias. 2024. “Mortality in the United States, 2022.” NCHS Data Brief 492. National Center for Health Statistics. https://dx.doi.org/10.15620/cdc:135850.

Kojola, Erik, and Phyllis Moen. 2016. “No More Lock-Step Retirement: Boomers’ Shifting Meanings of Work and Retirement.” Journal of Aging Studies 36: 59–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaging.2015.12.003.

Lee, Chaiwoo, and Joseph F. Coughlin. 2018. “Describing Life After Career: Demographic Differences in the Language and Imagery of Retirement.” Journal of Financial Planning 31 (8): 36–47.

Liu, Yinhan, Myle Ott, Naman Goyal, Jingfei Du, Mandar Joshi, Danqi Chen, et al. 2019. “RoBERTa: a Robustly Optimized BERT Pretraining Approach.” arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1907.11692.

Liu, Chang, Xue Bai, and Martin Knapp. 2022. “Multidimensional Retirement Planning Behaviors, Retirement Confidence, and Post-Retirement Health and Well-Being Among Chinese Older Adults in Hong Kong.” Applied Research in Quality of Life 17: 833–849. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-020-09901-7.

Markus, Hazel, and Paula Nurius. 1986. “Possible Selves.” American Psychologist 41 (9): 954–969. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.41.9.954.

Marshall, Victor W., Philippa J. Clarke, and Peri J. Ballantyne. 2001. “Instability in the Retirement Transition: Effects on Health and Well-Being in a Canadian Study.” Research on Aging 23 (4): 379–409. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027501234001.

Oyserman, Daphna, and Eric Horowitz. 2023. “From Possible Selves and Future Selves to Current Action: An Integrated Review and Identity-Based Motivation Synthesis.” In Advances in Motivation Science. Edited by Andrew J. Elliot. Academic Press: 73–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.adms.2022.11.003.

Raue, Martina, Lisa A. D’Ambrosio, Dana Ellis, Samantha Brady, and Joseph F. Coughlin. 2017. “Imagine Being 70: Future Possible Selves and Preparedness for Old Age.” The Annual Meeting of the Society for Personality and Social Psychology.

U.S. Census Bureau. 2023. “2023 National Population Projections Tables: Main Series.” www.census.gov/data/tables/2023/demo/popproj/2023-summary-tables.html.

Yin, Yimeng, Anqi Chen, and Alicia H. Munnell. 2024. “The National Retirement Risk Index: An Update from the 2022 SCF.” Issue in Brief 24-5. Center for Retirement Research at Boston College. https://crr.bc.edu/the-national-retirement-risk-index-an-update-from-the-2022-scf/.

Zaller, John, and Stanley Feldman. 1992. “A Simple Theory of the Survey Response: Answering Questions versus Revealing Preferences.” American Journal of Political Science 36 (3): 579–616. https://doi.org/10.2307/2111583.