Journal of Financial Planning: February 2024

Gary Smith is the Fletcher Jones Professor of Economics at Pomona College. He has written (or co-authored) more than 100 academic papers and 17 books, most recently The Power of Modern Value Investing—Beyond Indexing, Algos, and Alpha, co-authored with Margaret Smith.

Margaret Smith earned a simultaneous BA/MA summa cum laude from Yale as an economics major and a Ph.D. in business economics from Harvard University. She is a CERTIFIED FINANCIAL PLANNER™ professional, Certified Integral Coach, and an Accredited Enneagram professional. She is the founder of Prosperity Liftoff LLC, a fee-only financial planning and coaching company.

JOIN THE DISCUSSION: Discuss this article with fellow FPA Members through FPA's Knowledge Circles.

FEEDBACK: If you have any questions or comments on this article, please contact the editor HERE.

NOTE: Click on the images below for PDF versions

Many financial advisers recommend postponing the initiation of Social Security retirement benefits in order to increase the size of the benefits. In practice, however, most individuals choose lower benefits at an earlier starting age. Thus, Mark Hulbert, a senior columnist for MarketWatch, wrote, “The puzzle is why so many retirees claim their Social Security benefits at earlier ages, even though the nearly universal advice from financial planners is to delay claiming as long as possible” (Hulbert 2023).

Our analysis suggests that delaying benefits may often not be the best choice.

Background

The current full retirement age for Social Security benefits is a sliding scale between 66 and 67 years of age for people born between 1954 and 1960 and 67 years for people born in 1960 or later. Delaying the start of benefits past full retirement age increases the size of initial benefits by 8 percent for every year benefits are delayed up to age 70. Claiming before full retirement age reduces initial benefits by 5/9 of 1 percent every month for up to three years after early initiation and then by 5/12 of 1 percent every month for up to an additional two years. Table 1 shows the initial benefits using $1,000 as a monthly base for a full retirement age of 67.

Many financial advisers agree with Altig, Kotlikoff, and Ye (2022) that “the vast majority of American workers should delay taking their retirement benefits until 70.” Similarly, Fried (2019) writes that “scholarly research has unequivocally found that having the highest earner in a household wait until age 70 to claim Social Security is a crucial way to boost retirement income.”

Few follow this advice. In December 2022, 64 percent of all retired workers who were receiving Social Security benefits had chosen to begin receiving benefits before their full retirement age, let alone age 70 (Social Security 2023a). For those who initiated benefits in 2022, the most popular retirement age was the earliest possible age, 62, with 27 percent choosing this option. Only 10 percent were 70 years old.

People who choose to begin benefits early may need the monthly income to pay their ordinary living expenses. However, the recommendation that people wait until age 70 evidently assumes that such liquidity constraints are not important; it is simply a question of which starting age maximizes lifetime benefits. We will make this same assumption and focus on the simplest possible case—a person who is not working and does not have a spouse or other beneficiaries.

A Distraction

Some advisers think that the 8 percent increase in benefits for each year that the start of benefits is postponed past full retirement age represents an 8 percent rate of return. Among the many examples of well-informed people who draw that conclusion:

[Laurence] Kotlikoff points out that because Social Security accounts increase at the rate of 7 percent a year from age 62 to 66 and then at 8 percent a year until age 70, retirees get a better return there than they might get on the bonds inside their IRAs. “That’s a safe real return of 7 percent or 8 percent,” he said. “You can’t get anything close to that in the market (Darlin 2007).

If you wait to take your benefits until after your [full retirement age], Social Security will add an 8 percent delayed retirement credit to your eventual monthly payout each year you hold off, up until age 70. That’s a guaranteed return of 8 percent per year (Tucker 2020).

Between full retirement age and 70, the annual increase for delaying benefits is 8 percent per year, tax-free. That’s a steep hurdle for an investment strategy to clear (Carlson 2023).

This seductive conclusion is incorrect. On an annual basis, you are not forgoing $12,000 when you are 67 in order to get $12,960 when you are 68. You are forgoing $12,000 when you are 67 in order to get $12,960 instead of $12,000 when you are 68. If you die when you turn 69, your effective annual rate of return is negative 92 percent. The return will eventually turn positive as you live more years, but you cannot live long enough for the annual return to be 8 percent.

Implicit Rates of Return

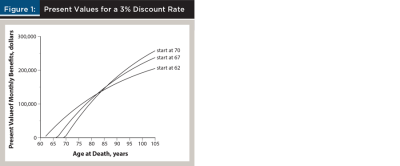

Using a $1,000 base for monthly benefits, Figure 1 shows the present value of lifetime benefits beginning at ages 62, 67, and 70 for various death ages and a 3 percent discount rate.

Since Social Security benefits are indexed for inflation, the benefits should be discounted by a real required rate of return. Our initial assumption of a 3 percent discount rate is but one of many possible values.

In Figure 1, the three starting ages give approximately the same present value for death ages around 84 or 85. The Social Security Administration’s 2023 actuarial life table based on 2020 data gives a life expectancy of 81 years for a 62-year-old male and 84 years for a 62-year-old female (Social Security 2023b). The advice that people who expect to live long lives should delay the start of benefits is sensible but hardly justifies the advice that “the vast majority of American workers should delay taking their retirement benefits until 70.” The vast majority of Americans do not live past their life expectancy.

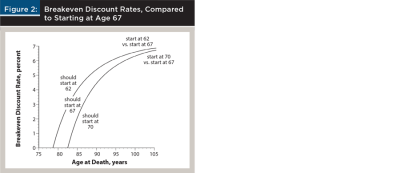

In addition, the lifetime present values depend not only on how long a person lives but also the discount rate. We can compare a decision to start receiving benefits at a full retirement age of 67 to other potential starting dates by determining the breakeven discount rate for which the two present values are equal. Figure 2 shows these breakeven rates for starting at age 62 or age 70, rather than age 67.

For discount rates that are higher than the breakeven rates in Figure 2, an earlier starting date is preferred. For example, at a 7 percent discount rate, initiating benefits at age 62 is more financially rewarding than starting at age 67 and initiating at age 67 is more rewarding than starting at age 70—no matter what the age at death.

The southeastern region of Figure 2 is where starting at age 70 has the highest present value—relatively low discount rates and high ages at death. The northwestern region of Figure 2 is where starting at age 62 has the highest present value—relatively high discount rates and low ages at death. The breakeven discount rates are relatively modest unless an individual lives well past their life expectancy.

It is also noteworthy that a substantial fraction of the population would receive more lifetime benefits from earlier starting ages, even using a 0 percent discount rate. Specifically, the lifetime benefits are higher for starting at 67 than for starting at 70 unless the person lives to age 82.5. On average, 49 percent of 67-year-old males and 36 percent of 67-year-old females do not live to age 82.5. With positive discount rates, even larger percentages are better off starting at age 67.

A Plausible Discount Rate

One reason for the enthusiasm of Altig, Kotlikoff, and Ye (2022) for delaying the start of Social Security benefits is that they assume a low 0.5 percent real required return because, “This is roughly the average real return on long-dated Treasury Inflation Protected Securities [TIPS] observed in recent years.” The historical average returns on 20-year and 30-year TIPS are 1.14 percent and 0.91 percent, respectively. The current rates are above 2 percent for 10-year, 20-year, and 30-year TIPS.

More importantly, Social Security benefits need not be discounted by the prevailing market interest rates on TIPS. The fact that Social Security recipients are receiving inflation-indexed annuity payments does not mean that this is how they want to invest these payments. They may not even want to invest their Social Security income. They may spend the benefits in lieu of borrowing money or liquidating stocks and incurring capital gains taxes. The real interest rate on their loans and the real return on their stock portfolios are almost surely not the interest rate on TIPS.

The annual real return on the S&P 500 has averaged 7 percent to 9 percent historically, depending on the starting date, but we should not assume it will do that well in the future simply because it has done that well in the past. When he was managing Yale University’s endowment, David Swensen generally assumed expected values for the future annual real returns on long-term Treasury bonds and the S&P 500 of 2 percent and 6 percent, respectively (Swensen 2009). A 60–40 stock–bond portfolio would have a 4.4 percent expected real return.

Walsh (2002) assumes a 4 percent after-tax real required return for calculating the present value of Social Security benefits. Coile, Diamond, Gruber and Jousten (2002) and Sass, Sun, and Webb (2008) both assume a 3 percent required real return.

Individuals should use discount rates that reflect their own personal needs and opportunities. Values of 3 to 4 percent are certainly plausible.

Expected Values

An appealing way to take into account a person’s unknown age at death is to weight the potential lifetime benefits by the probability of death at various ages. Consider someone who has just turned 62. For each potential starting age, we can calculate the present value of lifetime benefits for every possible age at death and then use a life table to determine the expected value of these present values.

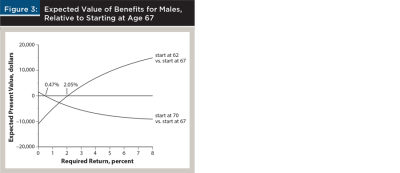

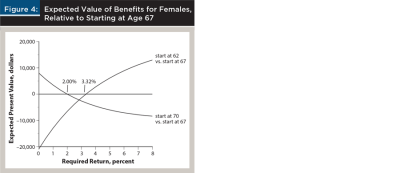

Figures 3 and 4 compare these expected values for starting ages of 62 and 70 to a starting age of 67. For males, the expected value for starting at age 70 is inferior to starting at age 67 unless the discount rate is less than 0.47 percent. A starting age of 67 has the highest expected value for a discount rate between 0.47 percent and 2.05 percent, and a starting age of 62 has the highest expected value for a discount rate above 2.05 percent. The payoff from postponing the start of benefits is larger for females because they are expected to live longer.

It is particularly noteworthy that the recommended 70-year-old starting age only has the highest expected value if the discount rate is quite low, particularly for males.

Discussion

We considered here the plain-vanilla case of an individual who is not working and does not have a spouse or other beneficiaries. The Social Security system is, in practice, extremely complex with detailed rules governing benefits for many different situations, including the spouses and children of retired workers, the spouses and children of deceased workers, and the parents of deceased workers.

One important consideration is that people who collect benefits while younger than their full retirement age lose $1 in benefits for every $2 they earn above an annual limit ($21,240 in 2023). This penalty can provide a decisive incentive for people who are still working to not start Social Security retirement benefits before 67, but it has no bearing on the decision to wait until age 70.

An often-persuasive argument for postponing the start of benefits to 70 is that surviving spouses who have reached their full retirement age are eligible for 100 percent of their deceased spouse’s benefits (again, there are many complicated related situations). On the other hand, if both persons are working, then (depending on their relative ages) it may make sense for the higher wage earner to delay benefits while the lower wage earner starts benefits early and then switches to survivors benefits when the higher wage earner dies.

Another issue is that people who do not have sufficient income or assets to buy the food or shelter they need have an obvious incentive to start their Social Security benefits early. However, advisers who recommend waiting until age 70 evidently assume that the people receiving this advice do not have these concerns. They may still be working and not plan to retire until they are 70 years old or older. They may have already retired and are receiving income from a defined-benefit retirement plan. They may have substantial assets inside and/or outside IRAs and other defined-contribution retirement plans. They may be receiving substantial alimony from a previous marriage. They may have the support of a spouse who has substantial income and/or assets. Whatever the reason, they evidently don’t need Social Security income before they turn 70; if so, they may not be dependent on such income after they turn 70. The fact that they don’t rely on Social Security income to meet their living expenses suggests that the stability of the real value of their Social Security benefits over their uncertain lifetimes is not a compelling reason for delaying benefits. The most relevant question is simply which starting age maximizes the present value of lifetime Social Security benefits.

Conclusion

Our calculations do not support the presumption that the vast majority of people who choose to start their Social Security retirement benefits before age 70 are making a mistake. For example, Figure 2 shows that with a 4 percent real return, a person has to live to 89 for it to be beneficial to delay the start of benefits from age 67 to 70. However, 77 percent of 67-year-old males die before 89 as do 65 percent of 67-year-old females. Age 70 is not the most financially rewarding age to initiate benefits unless an individual has a low discount rate and/or is confident they will live several years past their life expectancy.

There are admittedly nonfinancial considerations that may punish or reward the postponement of retirement benefits. For example, people who fear that the government will impose more onerous rules in order to keep the Social Security system from going bankrupt may reasonably conclude that they should lock in soon-to-be grandfathered benefits. On the other hand, delaying benefits may protect people from making foolish decisions like squandering their Social Security income on unnecessary frivolities instead of investing their benefits prudently.

For those who can control such impulses, receiving benefits before age 70, or even before full retirement age, and investing these benefits sensibly may well be a smart financial decision.

References

Altig, David, Laurence J. Kotlikoff, and Victor Yifan Ye. 2022, November. “How Much Lifetime Social Security Benefits Are Americans Leaving on the Table?” NBER Working Paper 30675. www.nber.org/papers/w30675.

Carlson, Bob. 2023, February 24. “Here’s More Evidence in Favor of Delaying Social Security Benefits.” Forbes. www.forbes.com/sites/bobcarlson/2023/02/24/heres-more-evidence-in-favor-of-delaying-social-security-benefits/?sh=2a0ab0396e96.

Coile, Courtney, Peter Diamond, Jonathan Grube, and Alain Jousten. 2002. “Delays in Claiming Social Security Benefits.” Journal of Public Economics 84 (3): 357–385.

Darlin, Damon. 2007, May 12. “A Contrarian on Retirement Says Wait.” New York Times. www.nytimes.com/2007/05/12/business/12money.html.

Fried, Carla. 2019, August 28. “Americans Sacrifice $3.4 Trillion by Claiming Social Security Too Soon.” UCLA Anderson Review. https://anderson-review.ucla.edu/social-security-delay/.

Hulbert, Mark. 2023, July 28. “Will You Claim Social Security Early or Hold Out as Long as Possible?” MarketWatch. www.marketwatch.com/story/will-you-claim-social-security-early-or-hold-out-as-long-as-possible-bbaf0b35.

Sass, Steven A, Wei Sun, and Anthony Webb. 2008, March. “When Should Married Men Claim Social Security Benefits?” Center for Retirement Research at Boston College. Number 8–4. https://dlib.bc.edu/islandora/object/bc-ir:104321/datastream/PDF/view.

Social Security. 2023a. “Annual Statistical Supplement, 2023, Tables 5.A3 and 5.A4.” www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/statcomps/supplement/2023/index.html.

Social Security. 2023b. “Actuarial Life Table.” www.ssa.gov/oact/STATS/table4c6.html.

Swensen, David F. 2009. Pioneering Portfolio Management: An Unconventional Approach to Institutional Investment. New York: Free Press.

Tucker, Scott. 2020. “Why Wait Until 70 to Take Social Security Benefits?” Kiplinger Personal Finance. www.kiplinger.com/retirement/social-security/601475/3-reasons-to-wait-until-70-to-claim-social-security-benefits.

Walsh, Thomas G. 2002. “Electing Normal Retirement Social Security Benefits Versus Electing Early Retirement Social Security Benefits.” TIAA-CREF Institute. www.tiaa-crefinsti-tute.org/pdf/research/speeches_papers/070102.pdf.

Read Next: “The Case for Delaying Social Security” by Wade Pfau, December 2015