Journal of Financial Planning: April 2022

Luke Delorme, CFP®, is the director of financial planning at American Investment Services in Great Barrington, Massachusetts. Luke lives in Great Barrington with his wife, two daughters, and dog Yogi.

NOTE: Please click on the tables below for PDF versions

JOIN THE DISCUSSION: Discuss this article with fellow FPA Members through FPA's Knowledge Circles.

FEEDBACK: If you have any questions or comments on this article, please contact the editor HERE.

One of the prominent new rules under 2020’s SECURE Act is that inherited IRAs for “non-eligible” beneficiaries must be distributed by the end of the 10th year after the decedent’s passing (spouses who inherit IRAs are not subject to this 10-year rule). Previously, these beneficiaries were allowed to stretch distributions over their lifetimes, which also delayed income taxes due on those distributions.

Beneficiaries who inherited IRAs since the beginning of 2020 should carefully consider the timing of distributions. Thoughtful analysis of this question can potentially avoid significant taxes. This is an opportunity for financial planners to add value for clients who have inherited an IRA since the beginning of 2020.

This article looks at whether to defer distributions until the end of 10 years or to spread distributions across the 10-year period.

Two primary factors in this decision are the investor’s current taxable income and the total value of the inherited IRA. The analysis suggests that spreading distributions across the 10-year period could significantly reduce federal income taxes compared with deferring distributions until year 10. However, the magnitude of this advantage is largely dependent on other income and the amount of the inherited IRA. Moreover, there are situations when deferring all distributions until the end of the 10th year could provide a tax advantage.

This article also discusses additional factors every planner should consider before offering a recommendation to clients. These secondary factors can significantly impact the optimal timing of distributions.

Defer or Spread Distributions?

All else equal, it is generally advisable to defer taxes. This default guidance might lead inherited IRA beneficiaries to simply wait until the end of the 10-year window to distribute the account. This would defer taxes on earnings and withdrawals. However, practitioners and beneficiaries should be aware this approach could trigger a substantially increased marginal and effective tax rate in the 10th year.

Instead of deferring distributions until year 10, an alternative is to amortize distributions over the 10-year window, which would spread the tax burden. This alternative would trigger income taxes on annual distributions. In addition, it could incur additional capital gains and income taxes if the distributions are re-invested into a taxable brokerage account. Nonetheless, it could be advantageous to spread distributions if the effective tax rate on distributions is relatively low.

This analysis uses some baseline assumptions to highlight the potential difference in federal income taxes under the two approaches: “lump sum” or “spread.” In general, the analysis shows that spreading distributions has the potential to be most favorable for larger inherited IRA amounts and for middle income earners.

Tables 1 and 2 demonstrate the impact of federal income tax savings for a sample household under the following assumptions:

- Inherited IRA value: $200,000

- Taxable income prior to distributions from inherited IRA: $150,000 (Married Filing Jointly)

- Pretax investment returns: 6.0 percent per year, of which 1.5 percent is earned through taxable income from investments (for simplicity, the analysis does not account for separate tax rates for qualified dividends and long-term capital gains distributions).

- Tax brackets are assumed to stay the same for 10 years.

- Federal taxes are paid out of distributions.

- State taxes are not included.

Table 1 shows the calculation of the after-tax value of waiting until year 10 for a lump sum distribution. The inherited IRA grows from $200,000 to $358,170, with no additional income taxes for the beneficiary during the first nine years.

In year 10, the entire account value is distributed, triggering a tax increase of $102,451. Assuming current tax brackets (ignoring the potential for changes in the tax code and changes due to inflation), the distribution would push this couple all the way through the 24 percent bracket and into the 32 percent bracket. The couple’s tax would increase by $102,451 due to distribution of the $358,170, for an effective rate of 28.6 percent on that lump sum payout.

Table 2 shows the alternative, in which distributions are amortized and spread across 10 years. The amortization schedule assumes a 6 percent annual growth rate; actual results will differ. The same assumptions about the household are used as in the first example in Table 1.

Under this alternative distribution strategy, annual income is increased by $27,124 per year strictly due to the draw. This would push the couple from the 22 percent tax bracket into the bottom of the 24 percent bracket, so a portion of this amount would be taxed at 24 percent. The effective tax rate on this additional income each year would be 22.3 percent, which is much lower than the 28.6 percent effective rate on distributions if the lump sum strategy is used.

It is assumed that the annual distribution is reinvested in a taxable brokerage account. The taxable account would incur additional taxes on income and dividends. It would also generate unrealized capital gains. The taxable portion of unrealized capital gains of $7,477 is subtracted from the after-tax value at the end of 10 years of $273,547, to arrive at the ending after-tax value of $266,070.

The ending after-tax value from amortizing distributions (Table 2) is $10,351 higher than the 10-year lump sum distribution strategy (Table 1). This is attributable to the sizable difference in the effective tax rate on distributions under the two methods (28.6 percent versus 22.3 percent). The additional capital gains taxes owed under the spread strategy are not large enough to make up this difference. This baseline analysis suggests that under many circumstances, default guidance of spreading distributions over 10 years will indeed provide a potential tax benefit versus deferring distributions for the entire 10 years.

When Does Deferral Make Sense?

The baseline analysis is not the end of the story. As noted, the spread strategy reinvests proceeds into a taxable account, which can incur additional taxes. For certain income levels and inherited IRA amounts, this additional tax burden could be larger than the potential tax savings of spreading the distributions.

If the lump sum at the end of the 10-year period is not projected to push the household into a significantly higher effective tax bracket, it may be worth waiting for the lump sum.

As an example, take a married household with $90,000 income and a $100,000 inherited IRA. An amortized annual drawdown of $13,587 would keep the household in the 22 percent tax bracket. Waiting until the end of year 10 would mean a distribution of $179,085, which would push the household into the 24 percent tax bracket. However, the effective tax rate on this lump sum distribution would be just 23.1 percent, which is not substantially higher than the 22 percent effective tax rate on the amortized withdrawals.

In this alternative example, the additional tax cost of reinvesting amortized distributions into a taxable account outweighs the benefits of amortizing distributions. For this example, the projected after-tax value is actually $3,977 higher with the lump sum strategy.

Examining Various Assumptions

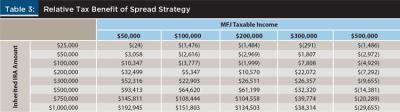

In Table 3, an estimated tax difference is estimated for a range of income levels and inherited IRA amounts. For this table, only the married filing jointly status is shown, but the lessons drawn are the same for single households albeit with different tax brackets.

For small inherited IRAs such as $25,000, it probably makes sense to defer distributions until the end of 10 years.

As the value of the inherited IRA increases, it generally makes sense to spread distributions across the 10 years. This is because of the potential for a much higher effective tax rate on the lump sum distribution in the 10th year.

But this is not always true. For households with much higher taxable income, who are already reaching into the highest tax brackets, deferring taxes until the 10th year could be preferable.

Table 3 shows that there is not a one-size-fits-all solution because of the relative nature of tax brackets. The largest potential for mismanagement of distributions is for low- and middle-income households with large inherited IRAs that choose to wait for a lump sum distribution. These households could see an added tax bill of well over $60,000, as is the case for a household with $200,000 taxable income and a $500,000 inherited IRA.

A planner can help by looking at a client’s current marginal tax rate and estimating the effective tax rate of distributions that are either amortized or taken as a lump sum. If there is a large difference, it will probably make sense to spread distributions across 10 years. If the difference in effective tax rates between the two strategies is small, it could make more sense to wait and take a lump sum distribution in year 10.

Additional Considerations

This analysis looks only at two primary factors in assessing spread distributions versus lump sum distributions. Individual and family circumstances will vary, and below are additional considerations that could drastically impact the optimal strategy for distributing inherited IRAs (Levine 2020).

Projected changes in earned income. Perhaps the most obvious and notable factor that could alter this analysis is if there is going to be a significant change in income during the subsequent 10 years. For example, if the inherited IRA owner is planning on retiring in two years at age 62 and delaying Social Security until age 67, there may be a five-year window during which taxable income is low. This could be an optimal time to distribute a larger share of an inherited IRA. Planners who are already evaluating potential Roth conversions in early retirement are likely accustomed to this type of complex analysis (Reichenstein and Meyer 2020).

Also, if the inherited IRA owner needs additional income, it could make sense to draw from the inherited IRA as needed prior to other retirement accounts.

State income taxes. State income taxes were not included in this analysis. However, to the extent that state income taxes are tiered, as they are in many states, it could strengthen the argument for spreading distributions.

If the inherited IRA owner plans on moving to another state, the change in state income taxes should be considered in the distribution timing.

Medicare premiums (IRMAA) and Social Security taxation. Medicare and Social Security increase the complexity of the analysis. For inherited IRA owners on Medicare or collecting Social Security, there is the potential that additional income can trigger higher Medicare premiums or additional taxation of Social Security benefits.

Financial planners should look at these potential impacts. There may be value in accelerating distributions prior to Medicare and Social Security, or there may be an argument for delaying distributions and taking them all at once so they only impact Medicare and Social Security for a single year (Reichenstein and Meyer 2018).

Conclusions for Practitioners

In financial planning, there are things we can control and things we can’t. It is difficult to predict the value or direction of markets and impossible to guess when and how much tax rates might change.

A skilled planner will seek to identify and tackle topics in which they can improve the financial position of the client with some confidence. For example, when Social Security previously allowed married couples to “file and suspend” benefits, it was a clear value-add for the financial planners who were proactive about recommending it to clients.

This is another such opportunity for planners to add value for clients. The topic of when and how to take distributions from an investment portfolio is full of difficult tax questions. Most nonprofessionals will hardly think twice about how to draw down an inherited IRA. Proactive financial planners with clients who have inherited IRAs since the beginning of 2020 have the potential to add value without having to guess which way the market or taxes are headed.

This brief analysis shows that thinking diligently about this question has potentially large tax benefits. Planners should explain to clients that while the optimal solution cannot be known in advance, a framework exists for making a sound decision.

Sidebar: Inherited IRA Distributions Checklist

Primary Factors

- What is the current income and tax bracket?

- How much is the inherited IRA?

- What is the effective tax rate on amortized distributions?

- What would be the effective tax rate on a lump sum distribution?

Secondary Factors

- Is income projected to increase or decrease substantially in the next 10 years?

- Does the client plan to move states within the next 10 years?

- Will the inherited IRA recipient make a significant life change in the next 10 years, such

- as marriage or divorce?

- Will the client be on Medicare within the next 10 years, and how close is the client to

- triggering IRMAA?

- Will the client be receiving Social Security benefits within the next 10 years, and how much of the benefit will be subject to taxation?

- Is there going to be a need for withdrawals from investment accounts within the next 10 years?

- Is the inherited IRA recipient expected to survive for the entire 10 years? If not, who is the subsequent beneficiary?

References

Levine, Jeffrey. 2020, February 19. “Strategies to Mitigate The (Partial) Death of the Stretch IRA.” Nerd’s Eye View. www.kitces.com/blog/secure-act-stretch-ira-401k-elimination-eligible-designated-beneficiary-retirement-accounts-minimize-taxes.

Reichenstein, William, and William Meyer. 2018. “Understanding the Tax Torpedo and Its Implications for Various Retirees.” Journal of Financial Planning 31 (6): 38–45.

Reichenstein, William, and William Meyer. 2020. “Using Roth Conversions to Add Value to Higher-Income Retirees’ Financial Portfolios.” Journal of Financial Planning 33 (2): 46–55.