Journal of Financial Planning: September 2017

Michael A. Guillemette, Ph.D., CFP®, is an assistant professor in the Department of Personal Financial Planning at Texas Tech University. He was previously an assistant professor at the University of Missouri. His publications, which focus on risk and insurance, have been featured in the Wall Street Journal, CNBC, and Bloomberg. Guillemette was a co-recipient of the 2015 American Council on Consumer Interests CFP Board Financial Planning Research Award and a co-recipient of the 2017 CFP Board Center for Financial Planning Best Paper Award in Investments. He has been invited to speak about his research to FPA chapters across the country.

Acknowledgements: The author thanks David Blanchett, Yi (Bessie) Liu, and financial advisers who attended the 2016 FPA of Greater Phoenix Symposium for their contributions to this manuscript.

Executive Summary

- This paper reviews both published and emerging research on different risks retirees in advanced age face and possible solutions financial planners can use to help clients overcome behavioral hurdles.

- Risk assessment questions that measure loss aversion, as well as reducing myopic behavior, can help keep clients in portfolios that align with their preferences.

- Older people have an inclination to reject evidence of declining skills, but if financial planners make clients aware of their declining cognitive and financial literacy abilities before retirement, they may be more willing to choose simplified and satisfactory solutions.

- Longevity “insurance” can be an effective way to help clients spend more during their early retirement years, while protecting them against the tail risk of running out of money prior to death. However, conflicts of interest within financial planning compensation models may hinder the demand for longevity insurance.

- A financial plan that includes ways the planner and client can work together to overcome inevitable risks in advanced age should improve the likelihood of helping clients achieve their financial and life goals.

It is inevitable that behavioral issues will arise in advanced age that can hinder retirees from reaching their goals. The purpose of this paper is to review the literature on risks clients face later in life and to provide financial planners with solutions to help their clients overcome these obstacles. This article consolidates research on age-related topics that are of critical importance to retirees and financial planners.

The first section provides information on client risk assessment. The second section is an extensive overview of risks clients face in advanced age and possible solutions financial planners can use to help their clients overcome behavioral hurdles, including the importance of making advisers and clients aware of declining literacy skills in advanced age, as well as the benefits of automated investments and lifetime income. The paper concludes with a discussion on the implications for planners.

Part I: Client Risk Assessment

Financial planners and advisers who provide retirement advice have a fiduciary duty to assess client risk preferences. The Department of Labor’s best interest standard requires “individualization,” which is a financial plan tailored to the investment objectives, risk tolerance, financial circumstances, and needs of a retirement investor. Informing clients about the investment philosophy of the financial planner (or firm) is an important first step within the investment planning process.

When a planner constructs a portfolio, it is important for the client to understand that the asset allocation consists of both financial and non-financial assets such as stocks, bonds, Social Security, real estate, and human capital (Blanchett and Straehl 2015). It is also valuable for planners to provide clients with a written IPS, as it can help clients maintain their asset allocation during market downturns. Research shows that clients who had a financial planner—and particularly those who had a written plan that included an IPS—were far less likely to shift their wealth into cash during the Great Recession (Winchester, Huston, and Finke 2011).

Risk capacity. Adequate portfolio risk assessment is vital in order to prevent clients from shifting assets to cash during a market decline. A client’s risk capacity, or wealth level, is different from their willingness to take risk. A client may have the financial capacity to take risk, but that does not necessarily mean they can avoid succumbing to behavioral traits, such as loss aversion, during market downturns.

Loss aversion. Loss aversion is the tendency for investors to weigh losses more than comparable gains from their last brokerage statement. When clients view their portfolio holistically, with both financial and non-financial assets, it can help to alleviate loss aversion.1

Measuring loss aversion is essential to accurately assessing a client’s risk preferences. Risk assessment questions that measure loss aversion—compared to questions that measure willingness to accept variation in spending—can more accurately capture individuals’ portfolio allocation preferences and recent investment changes (Guillemette, Finke, and Gilliam 2012). Questions that ask people the degree of risk they have taken with their financial decisions in the past and present periods are also helpful in determining portfolio allocation preferences and recent investment changes (Guillemette, Finke, and Gilliam 2012).

Spousal risk preferences. Charness, Gneezy, and Imas (2013) provided prevalent methods used to elicit individual risk preferences, but the literature on how to incorporate spousal risk preferences into an asset allocation is limited. However, research has shown that the share of risky assets in portfolios of two-person households increased with the risk tolerance of the spouse with greater bargaining power (Yilmazer and Lich 2015). Bargaining power included factors such as which spouse or partner had the final say on major family decisions (e.g., when to retire, where to live, or how much money to spend on a major purchase). Bargaining power was also assumed to increase based on the relative income the higher-earning spouse contributed to the household. Therefore, it’s important for financial planners to understand which spouse has greater bargaining power when assessing a couples’ risk preferences and building a portfolio allocation. Understanding how frequently each spouse evaluates investment returns may also provide a planner with clues about each spouse’s willingness to invest in stocks and bonds.

Myopic behavior. Myopic or shortsighted behavior is an important predictor of risk-taking. In one research study, students allocated 59.1 percent, on average, to a bond fund and the remainder to a stock fund when they were shown monthly returns. But when they were shown annual returns, they allocated 30.4 percent, on average, to the bond fund and the remainder to a stock fund (Thaler, Tversky, Kahneman, and Schwartz 1997). This finding was not just limited to students. It has also been found that workers invest more of their retirement savings in equities if they are shown long-term (rather than one-year) rates of return (Benartzi and Thaler 1999). In fact, professional day traders who constantly look at investment returns exhibit myopic loss aversion to a greater extent than students (Haigh and List 2005). These research findings emphasize the significance of understanding how frequently a client observes investment returns when assessing their risk preferences. They also highlight the importance of coaching clients to ignore short-run returns and reporting portfolio returns less frequently to reduce shortsighted behavior.

Another technique that may help reduce myopic behavior is the bucketing strategy—a behavioral technique designed to help clients link assets with a corresponding goal. When a financial planner and client are discussing the IPS, the planner frames liquid assets, bonds, and stocks as separate buckets of money. For example, liquid assets such as cash are framed as being in a short-term bucket used to fund spending needs over the next five years. Assets such as bonds are deemed to be in an intermediate-term bucket used to fund goals approximately six to 15 years away (e.g. education). Riskier assets such as stocks are in the long-term bucket that funds retirement goals. The bucketing strategy may reduce myopic behavior by helping clients focus on longer-term probabilities of payoffs for assets such as stocks and bonds.2

Part II: Risks in Advanced Age and Possible Solutions

Changing risk preferences. To what extent do client risk preferences change over time? Emerging research has suggested that individual risk perception and preferences may not be stable. Recent stock market declines, and even non-financial disasters such as earthquakes, are associated with a higher probability assessment of a future stock market crash by individual investors (Goetzmann, Kim, and Shiller 2016). This is likely due to the availability heuristic3 shifting an individual’s subjective probability assessment of a future crash (Goetzmann, Kim, and Shiller 2016).

Guiso, Sapienza, and Zingales (2013) found that a qualitative and quantitative measure of risk aversion among Italian bank customers increased substantially following the 2008–2009 global financial crisis, indicating that it was not just investors’ risk perceptions, but also their preferences, that changed in response to a decline in equity values.

Individual risk preferences may also be affected for a long period due to a traumatic market experience. The Great Depression was shown to have a permanent impact on individuals’ risk preferences and decisions, including a lower willingness to take financial risk, greater pessimism regarding future returns, and a lower likelihood of participating in the stock market (Malmendier and Nagel 2011). If investors experienced low stock market returns over their lifetime and participated in the stock market, they allocated a lower percentage of their liquid assets to stocks later in life (Malmendier and Nagel 2011). Consistent with Goetzmann et al. (2016), Malmendier and Nagel (2011) found that more recent return experiences had stronger effects on the willingness to take risk, particularly for younger people.

Preference for certainty. Age has a seemingly intuitive relation with the preference for certainty, as individuals become more myopic as their investment horizon shortens, thereby increasing the preference for more conservative assets (e.g., TIPS or annuities). Human capital, which can be quantified as the present value of future earnings, is a bond-like asset that declines in value as clients age. Rebalancing a client’s holistic portfolio likely requires a higher allocation percentage to bonds or annuities as the value of human capital falls. Reducing the standard deviation of the portfolio over time is also an optimal strategy if aging clients face an increasing preference for certainty and loss prevention.

Mather et al. (2012) conducted a study on the impact age had on the preference for certainty and found that older adults preferred certain gains and avoided sure losses to a greater extent than younger adults. As it pertains to attaining goals over one’s lifetime, younger adults reported a primary growth orientation whereas older adults reported a stronger orientation toward maintenance and loss prevention (Ebner, Freund, and Baltes 2006). If investors prefer greater certainty in advanced age, they should be more averse to an uncertain asset such as an equity investment in the S&P 500 Index.

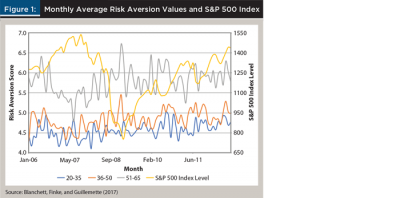

Emerging research provides evidence of equity-varying risk aversion in advanced age (Blanchett, Finke, and Guillemette 2017). Figure 1 shows the results of monthly average risk aversion, as measured by Morningstar, and S&P 500 values for three different age cohorts during the 2008–2009 global financial crisis.

As Figure 1 shows, when S&P 500 values fell, risk aversion rose for defined contribution investors over the age of 50.4 The descriptive changes in risk aversion were more pronounced during the bear market (January 1, 2006 to March 1, 2009) versus the bull market (April 1, 2009 to October 1, 2012) for older workers. The bear market correlations between the risk aversion score and the S&P 500 Index were –0.296 (ages 20 to 35); –0.559 (ages 36 to 50); and –0.696 (ages 51 to 65). In comparison, the bull market correlations were 0.158 (ages 20 to 35); 0.149 (ages 36 to 50); and 0.022 (ages 51 to 65). This suggests that variation in risk aversion may not just be dependent on age, but also whether workers experience stock market gains or losses. The age variable may also be capturing a shortening investment horizon and lower cognitive ability, which have been linked to increased myopic behavior5 and greater risk aversion (Dohmen, Falk, Huffman, and Sunde 2010), respectively.

Should older clients decrease stock allocations? An increased preference for certainty in advanced age raises the question of whether older investors should decrease their stock allocations later in life. Conventional wisdom suggests that clients should decrease their stock holdings and increase their allocation to bonds or annuities in advanced age due to a reduction in human capital and a shortening time horizon. However, research has indicated that it may actually be optimal to increase a client’s allocation to risky assets later in life.

Reducing retirement risk with a rising equity glide path (also referred to as a bond tent) has been found to reduce the probability of failure and magnitude of failure for client portfolios (Pfau and Kitces 2014). Pfau and Kitces (2014) reported that a portfolio that begins at 30 percent equities and finishes at 60 percent equities outperformed a portfolio that begins and finishes at 60 percent equities. Their results were consistent when the portfolio begins at 60 percent equities and ends at 30 percent equites. These results were confirmed by Delorme (2015) using a model of constant relative risk aversion. However, Blanchett (2015) found that a decreasing equity glide path was the optimal glide path shape across a wide range of scenarios. None of these research papers considered scenarios where the client’s risk aversion or loss aversion increased over time.

If client risk preferences are constant, then research supports that a rising equity glide path may be a good recommendation in certain scenarios. If, on the other hand, risk preferences shift and clients prefer greater certainty in advanced age, then a rising glide path may not be an appropriate strategy. The findings discussed previously emphasize the importance of reassessing client risk preferences in advanced age to determine whether they are constant. Future research should explore whether a rising equity glide path is optimal given increasing risk or loss aversion over time.

Declining cognitive ability and literacy. Client risk preferences are not the only trait that may change in old age. Clients face an inevitable natural decline in cognitive abilities over time. Inductive reasoning, spatial orientation, perceptual speed, numeric ability, and verbal memory all begin to decrease by age 45 (Schaie 1996) and begin to decline more rapidly by age 70.

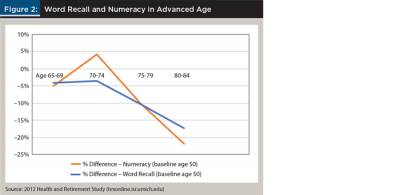

Figure 2 shows the sharp decline in word recall and numeracy in advanced age, which are associated with a lower propensity to hold stocks (Christelis, Jappelli, and Padula 2010).

Research has shown that a decrease in investment performance corresponds with the decline in cognitive ability (Korniotis and Kumar 2011), and financial literacy begins to decline after age 60, however, older individuals’ confidence in their financial literacy abilities remains constant over time (Finke, Howe, and Huston 2016). The decline in both fluid (e.g., word recall) and crystallized (e.g., define words) intelligence contributes to falling financial literacy scores (Finke, Howe, and Huston 2016).

Older people have an inclination to reject evidence of declining cognitive abilities. For example, older drivers often do not detect a decline in their driving abilities (Holland and Rabbitt 1992) despite a decrease in perceptual speed and spatial orientation over time. Holland and Rabbitt (1992) also showed that older drivers who took a driving exam became aware of their declining skills and modified their behavior to reduce the odds of getting into an auto accident.

If financial planners make pre-retirees aware of their impending decline in investment and financial literacy abilities, those clients may be more willing to make simplified and satisfactory financial decisions. This might include a greater demand for financial products that help simplify the decumulation decision during retirement. For consumers who do not receive expert advice from a fiduciary, automated investment products such as target-date funds can be helpful due to the benefits of diversification, automatic rebalancing, and possibly annuitization.

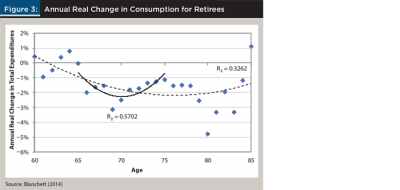

The retirement consumption puzzle. A retirement consumption puzzle exists, as retiree expenditures have been shown to actually decrease during retirement (Banks, Blundell, and Tanner 1998; Bernheim, Skinner, and Weinberg 2001; Ameriks, Caplin, and Leahy 2007). The life cycle hypothesis implies that individuals maximize happiness by smoothing spending during retirement (Modigliani and Brumberg 1954). The spending path should vary between clients based on factors such as risk preferences and expected mortality. For example, clients who are more risk tolerant should prefer greater spending during their early retirement years compared to less risk tolerant clients. Clients with a lower life expectancy should also prefer greater spending earlier in retirement. However, a “retirement spending smile” has been noted (see Figure 3), where the annual real change in consumption declines until ages 70 to 75 and then begins to increase later in life (Blanchett 2014).

It is important to disentangle the question of whether the reduction in spending in advanced age is due to a lack of retirement resources or choice. Browning, Guo, Cheng, and Finke (2016) investigated whether—despite the possibility of low future U.S. asset returns6 and longer life expectancies—retirees were spending an amount that would put them in jeopardy of running out of money during retirement. They found that wealthy retirees (the top 20 percent of wealth), on average, were not consuming an amount that would place them in danger of running out of money during retirement.

Given the findings of Blanchett (2014) and Browning et al. (2016), retirement income models may be overstating retirement living expenses. Increasing spending levels earlier in retirement appears to be a better retirement income strategy compared to a constant inflation-adjusted spending amount. As Blanchett (2014) pointed out, actual retiree spending did not even increase by inflation. Higher spending levels during the early retirement years is logical from a lifestyle standpoint as clients are healthier and may not be able to spend money on planned goals later in life as their health status declines. However, there may still be a need to set aside financial resources later in life due to increased medical costs and rising longevity.

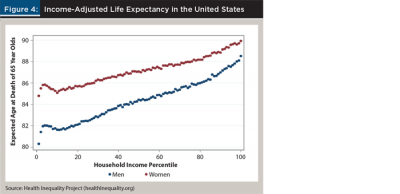

Longevity risk. Over the past half century, life expectancy in the United States has risen approximately one year every decade.7 One of the most important life expectancy factors is income, which has a dramatic effect on a client’s expected longevity. The wealthiest American men live 15 years longer than the poorest men, and the wealthiest American women live 10 years longer than the poorest women (Chetty et al. 2016). Figure 4 shows single U.S. life expectancy by income for a 65-year-old man and woman.

Life expectancy for the 5th percentile of household income is 82 years for men and 86 years for women. In comparison, for the 95th percentile of income (which is likely similar to the clientele of many fee-only advisers), life expectancy is 88 years for men and 90 years for women. Clients who live into advanced age may also live for an extended period. For example, in 2004 an 85-year-old man had a one-in-four chance of living to age 94 (Arias 2007), and joint life expectancy increases the odds of one spouse living closer to 100.

Longevity annuities. The best way to help clients align their retirement spending needs with an uncertain life span is by purchasing a longevity annuity. A male client who purchases $100,000 of a single-premium deferred annuity at age 65 would receive non-inflation-adjusted monthly payments of $3,955 a month beginning at age 85.8

In the current low interest rate environment, financial planners may advise that annuitization be delayed until interest rates rise. Some planners might be confident (or overconfident) that nominal interest rates will increase over the next few years, thereby increasing annuity payouts for their clients. However if interest rates do not rise or do not outweigh lost mortality credits, clients may pay more for a longevity annuity if the purchase is delayed.

Some planners may believe that a bond ladder is a superior alternative to an annuity. However, annuitization becomes a relatively more appealing option than building a bond ladder in a low interest rate environment because the increase in the cost of building a bond ladder is greater than the increase in the cost of buying an annuity when rates are low. A client spends principal and interest with a bond ladder arrangement, compared to spending principal, interest, and mortality credits with an annuity (Blanchett, Finke, and Pfau 2017). Mortality credits become more important with low interest in both scenarios, while a low discount rate for the bond ladder makes it increasingly expensive (relative to a longevity annuity) to fund spending planned for goals in the future (Blanchett, Finke, and Pfau 2017).

Research has shown that the way a planner frames an annuity to a client may have an impact on the demand for the product. Most people preferred a life annuity to a savings account when the choice was framed in terms of consumption (Brown, Kling, Mullainathan, and Wrobel 2008). Emerging research has also found that a longevity “annuity” is not as attractive when a longevity “insurance” option is viewed first (Guillemette, Jurgenson, and Sharpe 2017).

A financial planner’s compensation model is another factor that may influence the demand for longevity insurance. Planners who are compensated through a percentage of assets under management (AUM) have interests that closely align with their clients during the asset accumulation phase of the life cycle. However, post-retirement, planners who receive a percentage of AUM may have a financial incentive for their clients to limit spending, and that may include avoiding a large up-front cost to purchase longevity insurance. Such planners may rationalize a conservative decumulation strategy as reducing the likelihood that a retiree will outlive his or her portfolio assets. A satisfactory solution may involve the purchase of longevity insurance as a client approaches retirement in order to increase client spending during their early retirement years and protect against the tail risk of running out of money prior to death.

The U.S. government recently provided guidance on qualified longevity annuity contracts (QLACs) in retirement accounts. In 2014 the U.S. Treasury Department issued final rules in order to deal with the issue of QLACs and minimum distribution requirements (MDRs) from qualified retirement accounts. The final ruling stated that “a 401(k) or similar plan, or IRA, may permit plan participants to use up to 25 percent of their account balance or (if less) $125,000 to purchase a QLAC without concern about noncompliance with the age 701/2 MDRs. The dollar limit will be adjusted for cost-of-living increases.”9 It is important to note that QLACs should be purchased as insurance to protect a retiree from running out of portfolio income and not solely as a MDR avoidance strategy.

Implications for Planners

This paper outlined many of the behavioral challenges clients face later in life as well as potential solutions to help them overcome these obstacles. Whether a financial planner has a plan in place to assist older clients in the event that risks arise may ultimately define the planner-client relationship. However, even if a plan is in place, if it fails to include well-developed solutions to help retirees overcome behavioral hurdles, then retirement goals may still be in jeopardy.

Most clients exhibit myopic loss-aversion but there are ways financial planners can help counter the decision-making errors associated with these traits. Myopic behavior can be ameliorated by reducing the frequency in which portfolio returns are reported (e.g., from quarterly to annually). Loss aversion can also be reduced by educating clients on the holistic nature of their portfolio, which includes assets such as human capital, real estate, and Social Security. Providing clients with a written IPS and using a bucketing strategy are other ways financial planners can help clients maintain their asset allocation during market downturns.

Emerging research suggests that client risk perception and preferences may not be stable. A certainty effect has been observed in advanced age as well as equity-varying risk aversion. It is unclear whether a rising equity glide path is optimal if clients prefer to take less risk later in life. Client risk preferences should be reassessed later in life to ensure their portfolio strategy still aligns with their tolerance for risk.

Declining investment performance and financial literacy coincide with a decline in cognitive abilities in old age resulting in a greater propensity for clients to make financial mistakes. Clients have a tendency to resist the notion of inevitable declining abilities in advanced age. If an adviser is able to increase client awareness of declining financial literacy abilities before skills begin to deteriorate, then clients may be more likely to take steps to protect themselves from financial mistakes. This may include the recommendation of financial products by advisers that create illiquidity and prevent overspending.

A retirement consumption puzzle and rising longevity create a balancing act for planners. On the one hand, financial planners should strive to help clients enjoy their retirement savings earlier in retirement due to relatively higher health capital. On the other hand, longevity uncertainty creates the need for planners to protect clients from exhausting their retirement resources prior to death. One way to efficiently balance these conflicting goals is by purchasing longevity insurance. Longevity insurance provides financial advisers with a time frame of how long their clients’ retirement assets must last, potentially allowing for an increase in spending earlier in retirement. In addition, longevity insurance protects against the tail risk of a client depleting his or her retirement savings in the event that they live longer than expected. Although sales of fixed-rate deferred annuities are on the rise10, a financial conflict of interest may limit their demand among planners who are paid on a percentage of AUM.

Endnotes

- Sokol-Hessner et al. (2009) found that choosing to take a more holistic perspective reduced loss aversion.

- Hardin and Looney (2012) discussed how increasing time span over which prospective probabilities and payoffs are presented promotes broad framing and reduces myopic behavior.

- An availability heuristic is commonly defined as a mental shortcut that relies on immediate examples that come to mind when someone evaluates the likelihood of a future event.

- Statistically significant evidence of equity-varying risk aversion was not observed for cohorts under the age of 51 years. See Blanchett, Finke, and Guillemette (2017) for more.

- If one assumes that shortening the investment horizon also reduces the time span over which prospective probabilities and payoffs are presented, then it should increase narrow framing (myopic behavior).

- For a discussion on lower future U.S. asset returns, see Blanchett, Finke, and Pfau (2017).

- See u.demog.berkeley.edu/~andrew/1918/figure2.html for U.S. life expectancy figures for 1900 to 1998.

- The Lincoln National Life Insurance Co. annuity quote provided by Cannex as of August 3, 2017.

- See treasury.gov/press-center/press-releases/Pages/jl2448.aspx.

- See limra.com/Posts/PR/Data_Bank/_PDF/2016-4Q-Annuity-Estimates.aspx.

References

Ameriks, John, Andrew Caplin, and John Leahy. 2007. “Retirement Consumption: Insights from a Survey.” The Review of Economics and Statistics 89 (2): 265–274.

Arias, Elizabeth. 2007. “United States Life Tables, 2004.” National Vital Statistics Reports 56 (9): 1–40.

Banks, James, Richard Blundell, and Sarah Tanner. 1998. “Is There a Retirement-Savings Puzzle?” American Economic Review: 769–788.

Benartzi, Shlomo, and Richard H. Thaler. 1999. “Risk Aversion or Myopia? Choices in Repeated Gambles and Retirement Investments.” Management Science 45 (3): 364–381.

Bernheim, B. Douglas, Jonathan Skinner, and Steven Weinberg. 2001. “What Accounts for the Variation in Retirement Wealth Among U.S. Households?” American Economic Review 91 (4): 832–857.

Blanchett, David M. 2014. “Exploring the Retirement Consumption Puzzle.” Journal of Financial Planning 27 (5): 34–42.

Blanchett, David M. 2015. “Revisiting the Optimal Distribution Glide Path.” Journal of Financial Planning 28 (2): 52–61.

Blanchett, David M., and Philip U. Straehl. 2015. “No Portfolio is an Island.” Financial Analysts Journal 71 (3): 15–33.

Blanchett, David M., Michael S. Finke, and Michael A. Guillemette. 2017. “The Effect of Advanced Age and Equity Values on Risk Preferences.” Available at ssrn.com/abstract=2961481.

Blanchett, David M., Michael S. Finke, and Wade D. Pfau. 2017. “Planning for a More Expensive Retirement.” Journal of Financial Planning 30 (3): 42–51.

Brown, Jeffrey R., Jeffrey R. Kling, Sendhil Mullainathan, and Marian V. Wrobel. 2008. “Why Don’t People Insure Late-Life Consumption: A Framing Explanation of the Under-Annuitization Puzzle.” National Bureau of Economic Research paper No. w13748.

Browning, Chris, Tao Guo, Yuanshan Cheng, and Michael S. Finke. 2016. “Spending in Retirement: Determining the Consumption Gap.” Journal of Financial Planning 29 (2): 42–53.

Charness, Gary, Uri Gneezy, and Alex Imas. 2013. “Experimental Methods: Eliciting Risk Preferences.” Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 87: 43–51.

Chetty, Raj, Michael Stepner, Sarah Abraham, Shelby Lin, Benjamin Scuderi, Nicholas Turner, Augustin Bergeron, and David Cutler. 2016. “The Association Between Income and Life Expectancy in the United States, 2001–2014.” Jama 315 (16): 1,750–1,766.

Christelis, Dimitris, Tullio Jappelli, and Mario Padula. 2010. “Cognitive Abilities and Portfolio Choice.” European Economic Review 54 (1): 18–38.

Delorme, Luke. 2015. “Confirming the Value of Rising Equity Glide Paths: Evidence from a Utility Model.” Journal of Financial Planning 28 (5): 46–52.

Dohmen, Thomas, Armin Falk, David Huffman, and Uwe Sunde. 2010. “Are Risk Aversion and Impatience Related to Cognitive Ability?” The American Economic Review 100 (3): 1,238–1,260.

Ebner, Natalie C., Alexandra M. Freund, and Paul B. Baltes. 2006. “Developmental Changes in Personal Goal Orientation from Young to Late Adulthood: From Striving for Gains to Maintenance and Prevention of Losses.” Psychology and Aging 21 (4): 664–678.

Finke, Michael S., John S. Howe, and Sandra J. Huston. 2016. “Old Age and the Decline in Financial Literacy.” Management Science: 213–230.

Goetzmann, William N., Dasol Kim, and Robert J. Shiller. 2016. “Crash Beliefs from Investor Surveys.” National Bureau of Economic Research paper No. w22143.

Guillemette, Michael A., Jesse Jurgenson, and Deanna Sharpe. 2017. “Determinants of the Stated Demand for Longevity Annuities.” Available at papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2931446.

Guillemette, Michael A., Michael S. Finke, and John E. Gilliam. 2012. “Risk Tolerance Questions to Best Determine Client Portfolio Allocation Preferences.” Journal of Financial Planning 25 (5): 36–44.

Guiso, Luigi, Paola Sapienza, and Luigi Zingales. 2013. “Time Varying Risk Aversion.” National Bureau of Economic Research paper No. w19284.

Haigh, Michael S., and John A. List. 2005. “Do Professional Traders Exhibit Myopic Loss Aversion? An Experimental Analysis.” The Journal of Finance 60 (1): 523–534.

Hardin, Andrew M., and Clayton Arlen Looney. 2012. “Myopic Loss Aversion: Demystifying the Key Factors Influencing Decision Problem Framing.” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 117 (2): 311–331.

Holland, Carol A., and Patrick Rabbitt. 1992. “People’s Awareness of Their Age-Related Sensory and Cognitive Deficits and the Implications for Road Safety.” Applied Cognitive Psychology 6 (3): 217–231.

Korniotis, George M., and Alok Kumar. 2011. “Do Older Investors Make Better Investment Decisions?” The Review of Economics and Statistics 93 (1): 244–265.

Malmendier, Ulrike, and Stefan Nagel. 2011. “Depression Babies: Do Macroeconomic Experiences Affect Risk Taking?” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 126 (1): 373–416.

Mather, Mara, Nina Mazar, Marissa A. Gorlick, Nichole R. Lighthall, Jessica Burgeno, Andrej Schoeke, and Dan Ariely. 2012. “Risk Preferences and Aging: The ‘Certainty Effect’ in Older Adults’ Decision Making.” Psychology and Aging 27 (4): 801–816.

Modigliani, Franco, and Richard H. Brumberg. 1954. “Utility Analysis and the Consumption Function: An Interpretation of Cross-Section Data,” In: Kurihara, K. K., ed., Post-Keynesian Economics, New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press.

Pfau, Wade D., and Michael E. Kitces. 2014. “Reducing Retirement Risk with a Rising Equity Glide Path.” Journal of Financial Planning 27 (1): 38–45.

Schaie, K. Warner. 1996. “Intellectual Development in Adulthood.” In J.E. Birren and K. W. Schaie, eds., Handbook of the Psychology of Aging, 4th edition, San Diego, Academic Press: 266–286.

Sokol-Hessner, Peter, Ming Hsu, Nina G. Curley, Mauricio R. Delgado, Colin F. Camerer, and Elizabeth A. Phelps. 2009. “Thinking Like a Trader Selectively Reduces Individuals’ Loss Aversion.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 106 (13): 5,035–5,040.

Thaler, Richard H., Amos Tversky, Daniel Kahneman, and Alan Schwartz. 1997. “The Effect of Myopia and Loss Aversion on Risk Taking: An Experimental Test.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 112 (2): 647–661.

Winchester, Danielle D., Sandra J. Huston, and Michael S. Finke. 2011. “Investor Prudence and the Role of Financial Advice.” Journal of Financial Service Professionals 65 (4): 43–51.

Yilmazer, Tansel, and Stephen Lich. 2015. “Portfolio Choice and Risk Attitudes: A Household Bargaining Approach.” Review of Economics of the Household 13 (2): 219–241.

Citation

Guillemette, Michael A. 2017. “Risks in Advanced Age: A Review of Research and Possible Solutions.” Journal of Financial Planning 30 (9): 48–55.