Journal of Financial Planning: September 2011

"Alternative” investments are going mainstream, but can planners recommend them to their clients today with confidence? Increasingly, the answer appears to be yes—if they leverage the rapidly growing body of knowledge, analytical insights, professional due diligence, and specialized investment services available in the wake of the proliferation of alternative investment opportunities and strategies.

Perhaps for that reason, nearly half (49 percent) of planners responding to a recent FPA survey on alternative investments1 reported they are “confident” in their knowledge of alternative investments, and another 15 percent report being “very confident.”

It was not always that way. Or at least some who were confident should not have been. “During 2008–2009, one of the glaring things that came out was that a lot of advisers were recommending things they didn’t understand”—with disastrous consequences, recalls Jeffery Nauta, CFP®, CFA, CAIA, a principal with Henrickson Nauta Wealth Advisors in Belmont, Michigan. He refers in particular to structured mortgage products that imploded, and hedge funds that slammed the “gates” on unwitting investors and their advisers, creating unanticipated liquidity crises and significant financial losses.

Nauta takes his professional investment education seriously. In addition to being a CFP® certificant he is a CFA and, because of his strong interest in alternative investments, a CAIA, or Chartered Alternative Investment Analyst—a credential held by more than 5,000 individuals worldwide.

There are good reasons to hit the books (and the websites, blogs, journals, seminar circuit, and offering documents) before moving too aggressively into the world of “alts.” Those reasons boil down to common features of many categories of alternative investments usually not found in traditional “long-only” equity and debt instruments. Some of the basics, offered by Keith Black, Ph.D., CAIA, an associate director of curriculum for the CAIA Association, include:

- Leverage: The use of leverage, of course, magnifies potential gains or losses on an investment, so understanding how it might operate in a particular investment is critical.

- Short selling: While not conceptually difficult to grasp, short selling is a paradigm shift for traditional investors.

- Use of derivatives: Needless to say, some derivative instruments and the strategies they support require particularly careful scrutiny.

- Illiquidity: Not all alternative investments are illiquid (some, including commodity ETFs, can be highly liquid). But those that are illiquid, including private placement hedge fund and private equity structures, require careful analysis.

- Non-normal returns and “fat tail” risk: Investment return distributions on alternative investments tend to feature a higher proportion of outliers (positive and negative) than conventional investments.

- Manager due diligence: Portfolio managers running alternative strategies can be more critical to the success of the investment, yet they are also more challenging to assess (see the sidebar “Due Diligence Fundamentals”).

Keith Black stresses, however, that planners need not be intimidated by the homework required to become competent at understanding and recommending alternative investments. “A lot of the building blocks of alternative investments are simply fixed-income and equity investments, just in different wrappers or different packages.”

Philosophy, Process, and People

Nauta concurs: “At the end of the day, you are evaluating philosophy, process, and people—the same as you would with a traditional investment.” When it comes to “black box” computer-based trading strategies embedded within some hedge funds, Nauta says it’s not necessary to be able to build that black box, only to understand its risk and return properties.

One man who has devoted his career to shedding light on the topic is Thomas R. Schneeweis, Ph.D., president of Alternative Investment Analytics LLC, a professor of finance at the Isenberg School of Management at the University of Massachusetts in Amherst, founding editor of the Journal of Alternative Investments, and a founding board member of the CAIA Association. “The burden on financial advisers,” Schneeweis says, “is just understanding the strategies and how, in theory, they’re going to work—when they should make money, and when they should lose money.”

The sophistication of underlying strategies, compounded by the possible use of leverage and the broad mandate typically given to alternative investment managers, is sufficient to keep academics like Schneeweis busy conducting research and educating finance students on the topic. But understanding why and how products provide the return—the economic and financial conditions under which products are likely to perform well or poorly—represents the “bulk” of what aspiring CAIAs must learn.

Much of the 645-page CAIA Level 1 exam preparatory textbook An Introduction to Core Topics in Alternative Investments by Mark J. P. Anson covers that territory in great detail.2 The universe of alternative investments covered in the book consists of real estate, commodities and managed futures, private equity, credit derivatives, and hedge funds.

Time to Make Money?

The question of when real estate investments (both REITs and private equity formats) “should” or “should not” make money—and how much—can be attacked from several angles. The CAIA Level 1 textbook, for example, offers historical correlation patterns between several real estate sectors and other asset classes. It also guides analysts to assess real estate investment portfolios through the three-tiered world of “core,” “value-added,” and “opportunistic” properties.

Anson’s treatment of commodity investments includes a similar detailed, conceptual grounding and economic rationale, including correlation patterns between various commodity segments and the business cycle, inflation, and the market performance of financial assets. The economic underpinnings of private equity investments and credit derivatives are also laid out to guide prospective investors in those sectors.

Hedge funds, in all their variety, represent one of the most versatile access points for alternative investments. Accordingly, they are given the greatest attention in Anson’s book. One of several chapters on hedge funds includes a description of more than a dozen hedge fund strategies, illustrating the most basic analytical task planners face in gaining a comfort level with alternative investments—becoming acquainted with managers’ varied paths for making money.

Three of the more focused hedge fund strategies described:

- Activist investing: Fund managers amass a significant block of stock in a handful of public companies with the intention of bringing about corporate governance reforms that will result in a higher valuation of the company’s stock.

- Convertible bond arbitrage: The fund manager buys convertible bonds, but hedges the equity interest inherent in the bonds by selling options on that stock or actual shares of the stock.

- Volatility arbitrage: The strategy involves exploiting differences in the volatility-based component of an option price of different option contracts covering the same stock.

Some hedge fund strategies and the economics that drive them may be more challenging to digest than others. For example, the managers of “global macro” hedge funds essentially are given free rein to invest in any country and asset class that suits their fancy.

“They take large positions depending on the hedge fund manager’s forecast of changes in interest rates, currency movements, monetary policies, and macroeconomic indicators,” according to Anson’s description of these funds in the CAIA textbook. Analyzing such funds involves assigning greater weight to deal structure and particularly to a hard-nosed assessment of the manager and the operation that supports him or her.

Hedge Fund Manager Due Diligence

When pressed to explain his methods, one hedge fund manager told Anson, “Basically, I look at screens all day, and go with my gut.” Anson was not impressed. He and other veteran analysts emphasize that manager due diligence, as critical as it is with traditional investments, is even more so with alternative investments—particularly hedge funds. The reasons include the following:

- Alternative asset managers tend to concentrate their portfolios on relatively smaller numbers of investments.

- The limited partnership legal structure, used by typical hedge funds, contains fewer investor protections and transparency requirements than the Investment Company Act of 1940 governing mutual funds.

- Discretion granted to hedge fund managers under the typical partnership agreement allows them to freeze redemptions (to “gate” the fund).

In short, “On the mutual fund side, you’re less worried that it’s being run by a Madoff,” Nauta says.

Manager due diligence efforts fall into three categories: qualitative, quantitative, and operational soundness.

As the chief investment officer for Constellation Investment Partners, an 80-year-old family office in West Palm Beach, Florida, Henry Paret, CFA, has performed a lot of due diligence on hedge fund managers over the past decade. “You almost need to be a psychologist to get into their head to understand what they’re capable of,” he says. The crucible of 2008 gave Paret an important lens to conduct his assessment of managers’ performance.

Analysts’ qualitative assessments of managers seek answers to a host of questions, including:

- Is performance based on a consistent pattern, or just a few lucky picks?

- Does the manager really know how to construct a strong portfolio, or is he or she merely a good stock (or other asset) picker?

- Is the manager accessible and reasonably transparent about his or her transaction history and decision-making process?

Beyond the Charm

Frequently, qualitative assessments are not cut and dried, and require some detective work. Erin Davis, CAIA, an investment manager at an institutional multi-family office in San Francisco, California, recalls the challenge of deciding whether to place some client money with a “charismatic and charming” hedge fund manager who had a compelling story to tell. A different picture began to emerge when she interviewed some of his former associates. She decided not to invest with him, a decision that was subsequently validated in her mind when the manager abruptly fired his entire staff.

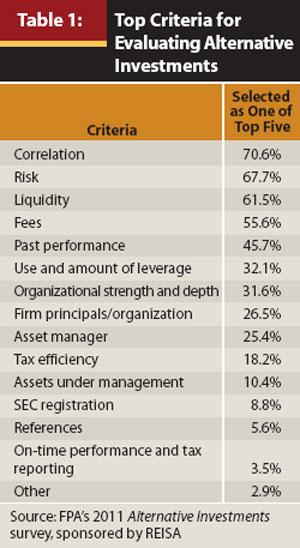

It may be noteworthy that financial planners responding to the recent FPA survey on alternative investments placed only average emphasis on the asset manager and asset management organization, when asked to identify their top five criteria for evaluating alternative investment products (see Table 1).3

Quantitative evaluation of alternative investment manager performance can be a highly subjective process, analysts say. It is also a function of the asset class involved—whether the goal is simply to provide returns that hedge and serve as a counterweight to the performance of the traditional side of the portfolio. As indicated in Table 1, an alternative investment’s correlation to traditional investments was the most frequently identified “top five” evaluation criterion.

Avoiding “Artificial Benchmarks”

When evaluating hedge fund managers, Paret and others emphasize that quantitative performance assessment is based on the goals and expectations set out for that manager. “We like to give money to managers with an open mandate. We don’t want to create some sort of artificial benchmark they need to hug. They should be doing things unique to their own skill set,” Paret explains.

That hasn’t gotten in the way of the creation of hedge fund indices, however. Hedge Fund Research Inc. (HFR), perhaps the largest financial research and consulting organization dedicated to the hedge fund industry, has created several indices, including the HFRX and the HFRI, covering multiple hedge fund strategies. One analyst interviewed for this article doesn’t consider those benchmarks terribly useful, but noted that “retail clients” like to see how their funds’ performance compares with the indices. HFR and other research organizations, including Bourne Park Capital, Cambridge Associates, Morningstar, and Financial Research Corp., are among many that can support planners in their due diligence efforts in selected corners of the alternatives world. The website allaboutalpha.com offers an excellent starting point for planners to begin expanding their expertise and finding additional resources on alternatives.

Quantitative measurements used to screen and judge hedge funds are many, including screens applied to conventional investments. Several identified by analysts interviewed for this article include:

- Use of leverage: The investor’s or adviser’s appetite for leverage is highly individualized.

- Value at risk (VaR): A statistical tool for gauging the most that can be lost under normal market conditions over a particular time horizon with a specified confidence level.

- Maximum drawdown: How much has a fund dropped in net asset value over the period measured?

- Risk-adjusted performance: “You know, not all 10 percent rates of return are created equal,” one analyst says.

- Market-cycle survival: How has the manager performed during bad times and good?

Operational Soundness

Operational soundness—the strength of the infrastructure supporting the manager and carrying out the administrative functions of asset management—does not escape analysts’ scrutiny. The smaller the firm, the greater the operational due diligence needed.

Paret says he wants to know, among other things, “Who’s next in line? Who’s doing the work? How are they compensating the analyst who’s out there kicking the tires?”

Getting answers to those and other measures of operational soundness, Davis’s team will develop relationships with “the whole team.” She and her own due diligence team don’t stop there, however. They will check references and talk to others not identified on the reference list who know people within the organization in question. Organizational due diligence also involves calls to former investors and prime brokers for the firm.

A strong organization may reflect a quality Greg Brousseau, co-CEO of the Central Park Group, a New York-based alternative investments company, says he seeks in key executives of asset management companies: knowing how to run a business. To gain insights on that capability, he examines how compensation and equity are distributed, how the business is organized, expectations of its longevity, and policies governing personal trading by staff members.

Legal Structure

If analysts are satisfied with the strength of the asset manager and the organization that supports him or her, they can turn their attention to the legal structure of an alternative investment fund, and the fee structure. As indicated in Table 1, the majority of advisers in the FPA Research Center poll considered fees among their top five alternative investment screens.

In the private placement hedge fund partnership structure, the extent of a manager’s ability to “gate” (block) asset redemptions in a liquidity crunch is a subject of particular focus for alternative investment analysts. Also, prior to the 2008 financial crisis, when many investors were less discriminating in hedge fund selection, rich fee structures were commonplace. They don’t always hold up to scrutiny, however.

One of Mark Anson’s “top 10 hedge fund quotes” from his book tells the story. Although a “2 and 20” fee structure is common among seasoned hedge funds (the manager earns a 2 percent asset management fee and 20 percent of profits), Anson does not deem it appropriate for new players. A pair of relative novices pitched its services to him when he was working with the California Public Employees’ Retirement System. When asked to justify a 2 and 20 fee structure in light of their lack of experience, they replied: “If we don’t charge 2 and 20, nobody will take us seriously.” The moral of the story, according to Anson: avoid managers seeking to justify their fees “based on what they think the market will bear,” rather than their talents.

Of course, some red flags are harder to miss than others in the expanding world of alternative investments. Selection criteria highlighted in this article represent a mere sampling of the most basic factors for several alternative asset categories. Even the most analytically astute and diligent investment professionals see a benefit in delegating some or all of the asset manager selection process to specialists.

The Role of Specialist Firms

Jon Sundt, president and CEO of Altegris, an alternative investments platform provider in La Jolla, California, explains, “The universe of talented money managers is vast. The biggest challenge for the adviser is, how do I find the talent? How do I do the due diligence? How do I get access?”

“Even if you can find the best managers in the world, a lot of them have minimums of $5 million, $10 million, or $20 million,” he adds. “Our job is to find the best alternative investment managers in the world, and then package them.”

While not extremely crowded—at least not yet—the field of firms that help advisers find and gain access to alternative asset managers includes some large and well-established organizations. In addition to Altegris, some of the key players include AQR Funds, Central Park Group, Fortigent, Hatteras Funds, Mount Yale Capital, and Rydex SGI. Each has its own strategy, market segment, manager investment style preferences, services, and product menu—although several compete with each other. What unites them is manager due diligence—“a huge part of what we do,” one executive explains.

Some have harnessed the mutual fund structure to address a common investor desire for liquidity and transparency, although not all pursue that strategy. Incentive-based compensation formulas demanded by some top alternative asset managers are not permitted under the Investment Company Act. Similarly, the illiquidity, leverage, and short-selling strategies inherent in some alternative investments also preclude utilization of the mutual fund structure. Accounting and legal costs associated with 1940 Act compliance can also get in the way for smaller alternative funds.

“I believe the ‘40 Act fund structure severely handcuffs managers. If we are truly on the search for alpha, let’s remove the handcuffs and align the compensation with performance,” reasons Nauta.

Exchange-traded funds, particularly in the commodities sector, have become huge players in the alternatives world. But typically those vehicles just provide exposure to an alternative asset class or specific commodity; they do not serve the function of guiding advisers and investors to alpha-seeking asset management talent.

Strategies Within Strategies

The degree of specialization within some alternative asset categories may leave little doubt in planners’ minds that the services of a specialized asset management talent scout or fund-of-funds manager may be very helpful. For example, Central Park Group’s Brousseau attended a conference on investment opportunities for distressed corporate debt earlier this year, where he learned about a dozen strategies being pursued by managers specializing in that field.

Some specialist firms, such as Fortigent, counsel advisers on asset allocation models within the universe of alternatives and on the broader core-versus-alternatives decision; they also guide their clients on the selection of managers. Executives of these companies say they don’t keep their due diligence under wraps. “We’re willing to share the work we’ve done. We want them to reach the same comfort level we have on the managers they recommend” to their own clients, says one executive.

Outsourcing alternative asset manager selection to a specialist firm doesn’t absolve planners of the need for due diligence, of course; it merely changes the focus. Nauta compares the task of reviewing these firms with that of evaluating a fund of funds. Areas of focus include the firm’s manager analysis and selection process, credentials and reputation of the principals, fee structure, and investment structure.

“It is still important to evaluate the individual funds and products you’ll use from their platform,” Nauta advises. “If you are an RIA and the SEC comes knocking, they’ll want to see that you performed adequate due diligence on the product.”

With the effort he has made to acquire the expertise needed to analyze alternative investments and identify suitable specialized asset managers, Nauta does not worry much about regulators second-guessing his due diligence process. Nauta believes these efforts enable him to serve his clients well and give him a value-added service that contributes a competitive edge to his business—at least until the day when hedge funds, commodities, real estate, and the like become so common in client portfolios that the term “alternative” is rendered meaningless and disappears from the vocabulary of investments.

Richard F. Stolz is a financial writer and publishing consultant based in Rockville, Maryland.

Endnotes

- FPA’s 2011 Alternative Investments survey, sponsored by the Real Estate Investment Securities Association (REISA), was conducted by the FPA Research Center in May 2011 with 410 financial planners who use/recommend investments for at least some of their clients.

- Anson, Mark J. 2009. CAIA Level I: An Introduction to Core Topics in Alternative Investments. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. A new edition of the book will be published in late 2011.

- The scope of the survey covered all alternative investments, including such products as passive commodity-based ETFs where manager capabilities may not be a significant determinant of investment performance.

Sidebar

Due Diligence Fundamentals

There is as much art as science to evaluating hedge fund managers. Mark J. P. Anson, managing partner and chief investment officer of Oak Hill Investment Management, spans both realms in his book An Introduction to Core Topics in Alternative Investments.

Anson offers a detailed template for hedge fund manager evaluation. The following is a brief sampling of the kind of questions Anson poses to separate the wheat from the chaff:

- What is the source of your investment ideas?

- In which markets do your strategies perform best?

- What is the maximum capacity of your strategy?

- What is your strategy given the current market conditions?

- Do you hedge market, interest rate, credit, or currency risk?

- How do you decide which of these market exposures to hedge or maintain?