Journal of Financial Planning: November 2021

Patrick Geddes is the co-founder and former CEO of the Aperio Group, a $44 billion investment manager that works primarily with ultra-high-net-worth and institutional investors. Prior to co-founding Aperio, Patrick was the research director and CFO at Morningstar, and he taught graduate-level portfolio theory at UC Berkeley Extension. He is also the author of the upcoming book Transparent Investing, which teaches you how to rewire your brain and unlearn what you know about investing to help you to create a brighter financial future. For more information, visit https://patrickgeddes.co.

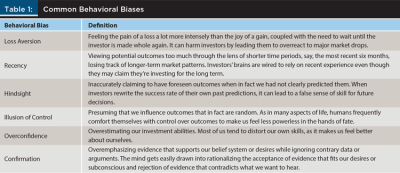

NOTE: Click on table below to view as a PDF.

Now that behavioral finance has gained traction across the investment industry, advisers have begun to incorporate psychological insights into helping clients avoid some of their worst counterproductive behaviors. Both advisers and clients increasingly acknowledge the benefit of paying attention to how our brains are wired, an approach rarely seen 30 years ago. It’s not that behavioral finance has replaced modern portfolio theory but that it has expanded our knowledge of how investors reach decisions, complementing the traditional view of the rational actor who always carefully chooses to maximize risk-adjusted return.

Almost all research on these biases has focused on the investor rather than the adviser. However, advisers are human beings, too, with brains that developed through evolution with tendencies toward some of the same well-documented biases. Shown below are some of the more commonly identified investor biases cited in published research.

We’ll focus not on just the behavioral bias as it manifests in investors but also on the interaction of an investor’s blind spots with potential biases we may exhibit as advisers.

Beginning with loss aversion, I’ve heard a number of advisers say that we add the most value by keeping clients on the straight and narrow like not letting someone sell out in a panic in the middle of a market collapse. Virtually every successful adviser who has been through a market rough patch could share stories of talking clients down off the ledge. Because of our knowledge of the importance of staying in the market, as advisers, we provide a healthy counterbalance to panic. That influence often creates enormous value in situations where clients might harm themselves through poor decisions motivated by their fear. As advisers, we too may dislike the emotional distress of serious bear markets, but our work with clients to provide a steadying influence means we’re able to avoid the trap of that particular bias.

Similarly, for those of us with experience with longer market cycles, we can offset recency bias by keeping the client’s perspective more centered on the longer term. We can also keep clients more grounded in the long term by helping them avoid fooling themselves through hindsight bias into thinking they could have and should have seen events like major bear markets coming.

Adviser biases may become more of a challenge, though, when we fall to the illusion of control or overconfidence. If part of our value proposition to clients lies in our claims to be able to pick the active strategies that will outperform the market, at that point, our incentives can open us up to our own biases, what’s often referred to as “motivated thinking.” For advisers, the risk of motivated thinking can include presuming an ability to pick winners in advance despite the overwhelming research of the difficult odds in doing so. While this is not the place for any in-depth discussions of the long-standing debate between proponents of active strategies and those of passive, there’s not much question that an inherent conflict of interest exists for advisers seeking to affirm that the odds of market-beating performance may be higher than research suggests. Of course, that doesn’t mean passive is always better or that active never succeeds, but as advisers, we can easily be drawn into preferring active strategies when we presume that such strategies will be perceived as more valuable by our clients.

As for our openness to the research on active strategies, confirmation bias remains a constant risk in any profession, and the financial advisory space is no different. In his book How We Know What Isn’t So, Thomas Gilovich (1997) summarizes the research on the widespread tendency to ignore evidence that doesn’t support our preferred position. For example, if someone subject to confirmation bias sees 10 academic articles critiquing the general success of their preferred strategy and then one article that supports it, the mind will ignore the inconvenient first 10 and latch onto the one bit of evidence as adequate proof. Reflecting the idea of conflicting incentives in a folksier tone, renowned muckraker Upton Sinclair observed nearly a hundred years ago, “It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends on his not understanding it!”

Some components of providing investment advice can prove to be rather tricky in terms of spotting biases. For example, when looking at how to construct a portfolio that maximizes risk-adjusted after-tax returns, many advisers add significant value to clients compared to what they might do on their own. Advisers can generally help with techniques like maximizing contributions to tax-advantaged accounts, explaining how to benefit from 529 plans for college savings, or choosing for clients taxable or municipal bonds based on which offers the higher after-tax return.

On the other hand, as previously stated, advisers may fall prey to overconfidence or the illusion of control by putting their clients in active strategies that may be hard enough to justify on a pre-tax basis, but even harder when taxes are included in the return calculation. In some excellent research from Morningstar from 2016, “Investing Taxable Money in Active Stock Funds? Bad Idea,” Jeffrey Ptak found the odds of picking a winning active strategy after tax (assuming the highest federal tax bracket) in the 10 years ending in 2015 were 5 percent, compared to a 95 percent chance of trailing. The outperformance for those lucky 1-in-20 active managers averaged 0.76 percent per annum, compared to a 95 percent chance of trailing by an average of –1.17 percent. Most professional gamblers will tell you those are pretty weak odds, but for advisers trying to justify active strategies for taxable accounts, the problem lies in the reality that the sexiest strategies are in general the least tax efficient. Boring strategies like indexing offer the simplest way to improve after-tax return over active strategies, but that may not be as appealing to advisers trying to impress clients.

How can we avoid our natural inclination to bias? In her recent book The Scout Mindset, Julia Galef (2021) describes some ways to help all of us test our own susceptibility to motivated thinking and self-serving bias. She offers a few thought experiments to nudge us away from our biases, including the “selective skeptic” test, where someone seeking justification might ask themselves, “if this evidence I view as not credible supported the opposite conclusions, would I suddenly view it with more respect?” In other words, she suggests pushing our minds to explore whether we prefer a certain set of data or research article because it reflects a rigorous methodology or because it supports our already existing belief. Galef makes the point that such thought experiments can help you “reveal that your reasoning changes as your motivations change.” She also recommends a gentle tolerance when encountering bias in oneself and others, viewing it ideally as a learning experience rather than as a reason for castigation.

As advisers, we all want to do right by our clients and provide them with the best possible financial outcomes. However, since as humans we too are often vulnerable to the same biases as our clients, we can’t ignore the possibility that our recommendations may reflect the financial impact on us as well as on our clients. By watching out for our own biases, we can minimize the negative impact of all types of bias upon our clients, thus achieving what motivates almost all advisers, serving our clients to the best of our professional abilities.