Journal of Financial Planning: November 2017

Ryan Grau, CVA, CBA, is the valuations director and a principal for FP Transitions. He is an authority on the topics of value, valuation, and business continuity planning across multiple industries.

What is my practice worth? This is a question that every independent financial adviser should ask, or has asked, at one time or another. Given that the value of a fee-based advisory practice is often the largest asset that most advisers own, it is a good question in need of good answers.

Countless valuation services and tools are offered up to help answer this question—some good, some bad. Very few business owners understand the valuation process, myriad decisions, and judgment calls necessary to arrive at a value. When it is time for you to determine the value of your life’s work, you need to understand certain value, and valuation, fundamentals so that you can get the right answer from the right expert every time.

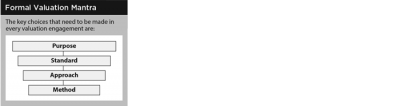

The starting place for most advisers who need a formal valuation is this simple mantra: purpose, standard, approach, and method. These are the key starting points in every valuation engagement. Any time a business appraisal is needed, the standard of value, approach, and method(s) used for estimating value should be tied directly to the purpose or reason that the valuation is being conducted. When you decide to sell your vehicle, for example, standards of value include both trade-in and private-party values, among others. Given the specific purpose (you want to sell your car), both values are correct even though it is the same vehicle. Still, only one standard is applicable based on the party you plan to sell to. This same concept applies to business appraisal valuations.

Purpose

Value is a function of purpose, and the answer is not universally applicable to every situation. Why have your practice valued? The most common reasons include:

Non-tax valuation: general knowledge, reporting to an owner, buyer, investor, or judicial authority in cases of:

- Sale or merge with a third-party

- Internal sale

- Dissolution, either marital or corporate

- Damages and other disputed matters

Tax valuation: reporting value to a tax authority in cases of:

- Charitable contributions

- Transfers to related parties

- Estate tax

- Grants and options

You need to articulate the answer to your chosen appraiser in order to determine the standard of value to be used, the approach (or approaches) to take, and the methods to be used. Incorrect assumptions regarding your purpose will yield an incorrect valuation result.

Any time you plan on making a business decision relating to the value of one of your largest assets, you should seek the assistance of a professional business appraiser (see the sidebar on page 27 for tips on doing so). When selecting an appraiser, ensure they have a thorough understanding of the financial services industry and that they have access to industry-specific, private-party transaction data. Most important, the appraiser needs to have a thorough understanding of your purpose and who will be on the receiving end of any value results.

Standard

The most common reason to value a practice is for mergers and acquisitions. The next most common reasons are divorces, internal sale of stock, and gifting/transfers to related parties. Depending on which purpose is applicable to your specific needs, the resulting value may vary significantly. The reason for the differences in value results from:

- The type of property being valued. Is it assets or stock?

- The standard of value. Value to whom and under what assumptions?

- Is the valued interest a controlling share or not?

- What is the level of marketability of the subject interest? Is it liquid?

For example, the most probable selling price of a 100 percent controlling interest of the assets of a practice being valued for the purpose of selling to a third-party in an arm’s length transaction, where the majority of the purchase price is financed over five or more years, will be valued higher than the fair market value of a 10 percent minority, non-controlling, non-marketable interest in the equity of the same practice on a cash or cash equivalent basis for the purpose of gifting stock. The delta between these values is much greater than a pro rata portion of the 100 percent interest. To clarify why, let’s explore how standards of value affect the value of your practice.

Although many standards of value are applicable to the appraisal of a business interest, the two most common standards in the financial services industry are fair market value and most probable selling price.

Fair market value. Fair market value is required when valuing shares and equity of a closely held practice for IRS/tax-related matters. The IRS wants to know what the cash value of the shares or units are worth. Often, financial advisers assume that a 10 percent interest in their company’s equity on a cash basis is worth a pro rata portion of what they could sell their practice for in the open market. Rarely is this the case. (Fair market value is also applicable when opining on the equity value of a business interest for a divorce, but this varies per jurisdiction.)

The term “fair market value” is one of the most commonly misunderstood and inaccurately used valuation terms. Of the last 5,000 practices we have appraised, valued, or offered opinions on, fair market value has almost never been an applicable standard of value for the purpose of valuing a practice when selling to a third-party in an arm’s length transaction; especially when the seller is providing post-closing consulting, an agreement to not compete, and is willing to finance the majority of the purchase price.

The definition of fair market value according to the International Glossary of Business Valuation Terms is: “The price, expressed in terms of cash equivalents, at which property would change hands between a hypothetical willing and able buyer and a hypothetical willing and able seller, acting at arm’s length in an open and unrestricted market, when neither is under compulsion to buy or sell and when both have reasonable knowledge of the relevant facts.” This definition is nearly identical to the one found in IRS Revenue Ruling 59-60.

The often overlooked, but key issue is that fair market value is considered “value in exchange” on a cash or cash equivalent basis. In other words, transferable property is sold in exchange for something of value, namely cash. This is logically inconsistent with how a typical financial advisory practice is bought and sold: less than 5 percent of all sales are completed on a cash basis, and the industry standard pricing multiples assign a value attributable to non-transferable property such as (1) the seller’s agreement to provide post-closing consulting to help transfer the assets (a consulting agreement); and (2) an agreement to not compete or solicit the clients subject to the purchase agreement. These are services that only the seller can perform; they are not “transferable property.” By ignoring these facts, a statement of fair market value could be inaccurate by as much as 15 to 25 percent which—as you can imagine—is an issue when the opinion of value is used for tax, divorce-related, or disputed matters.

It is worth noting that this standard of value is more of an academic standard than the reality of what an adviser could expect if he or she actually sold their practice to a third party. Most buyers and sellers who participate in an open marketplace are under some level of compulsion to buy or sell. If compulsion were not present, it stands to reason that a seller would never accept anything less than absolutely favorable deal terms at the highest value from his or her point of view. The inverse of this argument is applicable to buyers as well.

Most probable selling price. This standard of value best describes the value that a seller could expect to receive if he or she sold their practice to a third party in the financial services industry. It is defined by the International Business Brokers Association (IBBA.org) as: “The price for the assets intended for sale which represents the total consideration most likely to be established between a buyer and seller considering compulsion on the part of either buyer or seller, and potential financial, strategic, or non-financial benefits to the seller and probable buyers.”

The most probable selling price reflects the reality of the marketplace. For the sale of financial service practices, this standard of value assumes the sale, transfer, or acquisition is accomplished using a standard tax allocation strategy for the sale of capital and personal assets, resulting in the majority of the value ultimately being realized at long-term capital gains tax rates (presuming an adequate holding period for the capital assets). This value further assumes a 100 percent transfer of ownership interest in the customer list and files, personal and enterprise goodwill, consulting agreements with the seller(s), and a non-competition and/or non-solicitation agreement(s) from the seller(s). The majority of the purchase price is expected to be seller financed over a four- to six-year period at interest rates that are substantially lower than what third-party lenders would require.

Both fair market value and the most probable selling price can be determined using either the income or market approach (see below), and a professional business appraiser should be able to produce similar estimates of value using either. The key to successfully determining value from each approach is understanding the standard of value inherently produced by each approach and the necessary adjustments required based on the standard of value for the given purpose.

An income approach, for example, is going to produce a value consistent with fair market value. If this approach is used for the purpose of valuing a practice that is going to be sold to a third party in an arm’s length transaction—especially when seller financing is involved— adjustments need to be included to account for the cost of seller financing and any additional services or agreements a seller is willing to provide post-closing, such as a consulting agreement, a non-compete/non-solicitation agreement, etc.

A market approach, relying on the use of private company transactions in the financial services industry, will most often produce a value consistent with the most probable selling price (depending on the source of the data). Using this approach for an opinion of fair market value requires an analysis of the deal structure of the transactions.

Approach

The appraisal discipline has three generally accepted approaches to value: asset, income, and market approaches. These approaches are broad categories for various ways to value a business. Under each of these approaches are commonly used and accepted methods of valuation. Without an understanding of the purpose for the valuation or the appropriate standard of value, the correct application of these approaches is limited to a best guess.

Of the three valuation approaches, the easiest to understand and the most commonly used is the market approach. The asset approach is rarely used in our industry due to the lack of physical capital assets needed to produce revenue. The income approach is the most complex approach to value a closely held practice.

Methods

Market approach methods. The market approach has three common methods: (1) Guideline Public Company Method (GPCM); (2) the Public Company Transaction Method (PCTM); and (3) the Guideline Private Company Transaction Method (GPCTM).

GPCM and PCTM are often used to value financial service practices by appraisers who do not have access to comparable private company transaction data. These methods compare the practice being valued to the enterprise value of public companies in the same industry, but with market capitalization rates 20 to 40 times the size of the typical practice. In other words, these methods rely on the possibility that closely held financial service practices will sell for a price similar to that of a publicly traded C-Corporation.

Alternatively, GPCTM develops a value based on a group of five or more transactions of closely held practices that sold in a free and open market. The results from this method are grounded to previous transactions of similar companies and arguably provide the most reliable estimates of value for most practices in the industry. Unfortunately, the usefulness and accuracy of the GPCTM approach is limited to the number of transactions and quality of the information available to the appraiser.

Transaction data on financial service practices is often not readily available through industry databases such as the Institute of Business Appraisers, Bizcomps, Pratt’s Stats, and PeerComps. Moreover, available information is typically limited to one year of financial statements that may be much older than the actual transaction date. The best source of data when using the GPCTM for valuing a financial services practice can be firms that provide certified valuations, business brokerage, and consulting services.

Income approach methods. The income approach is a suitable approach for allowing the appraiser to forecast income and expenses, and project the future economic benefits that will flow to the owner(s). The two methods that fall under the income approach are stylistically similar, but contain underlying assumptions that make them mutually exclusive.

The first method, capitalization of earnings method, makes the assumption that growth of the practice or business will be uniform into perpetuity. This assumption manifests itself through one long-term sustainable growth rate that is used to capitalize a benefit stream, typically net cash flow to invested capital.

The second method, the discounted cash flow method, is based on the concept that the growth of the company will vary for a determined forecast period, typically five to 10 years. When performed correctly, this method forecasts the practice’s revenues, expenses, capital expenditures, and working capital requirement of the business until it reaches maturity. These forecasts are then discounted to their present value.

It is important to understand that the value produced using either method from the income approach will produce a cash or cash equivalent value consistent with the definition of fair market value. This can be observed by analyzing the sources from which the discount rates are developed—publicly traded C-Corporations. When was the last time you saw a market cap rate quoted at a price other than cash? When was the last time you purchased stock of a publicly traded company and the quote included anything about how you might finance the purchase?

If the source of the discount rate is derived from transactions of minority shares in a freely traded marketplace, then the value calculated from this apporach will represent a marketable, liquid interest. The very nature of a closely held company is a marketable, illiquid interest, and, therefore, is less valuable than a marketable liquid interest. As such, an additional discount to reflect the decreased liquidity of a closely held company should be applied when an income approach is used. This is common practice among business appraisers who are familiar with the use of the income approach. However, it is often skipped in models developed by those who do not specialize in the appraisal profession. Omitting this step means value may be overstated by as much as 25 percent. Appraisal pundits Shannon Pratt, Gary Trugman, Jeffrey Jones, and Rand Curtiss, all accredited by the American Society of Appraisers and the Institute of Business Appraisers, reached this conclusion in a conference sponsored by Business Valuation Resources.1

Conclusion

No single valuation approach and method works every time in every situation. If you’re told otherwise, it is usually by someone selling the one approach that they understand and that can be sold profitably. For this reason and others shared in this article, it is highly recommended that advisers wishing to sell their practices seek the professional assistance of a business appraiser or certified valuator who can employ the appropriate approaches and methods that tie value directly to the adviser’s purpose. This step is where the appraiser can help the adviser save money by accurately identifying the necessary scope of work to provide a defensible value.

Opining on the value of a financial services practice is contingent on the appraiser and on the adviser seeking to understand how the concepts of purpose, standard, approach, and method fit together to provide an accurate view of their practice’s value for a specific situation.

Endnote

- See Business Valuation Resources' "Valuing Small Businesses" (teleconference, Dec. 16, 2004.

Sidebar:

Tips for Finding an Appraiser

A practice’s value is ultimately decided by a willing buyer and a willing seller. However, without the proper application of the tools shared here by an accredited appraiser who understands how to apply them correctly for the adviser’s specific purpose, you cannot expect to receive a beneficial outcome. The use of unaccredited appraisal services or an online calculator to solve the needs of a specific purpose is often a fool’s errand.

The valuation profession, like the financial advice profession, requires a higher level of qualification, education, and experience. To find an accredited appraiser, look for the following designations:

- Certified Valuation Analyst (CVA)

- Certified Business Appraiser (CBA)

- American Society of Appraisers (ASA)

- Accredited in Business Valuation Credential (ABV)

Using a professional appraiser doesn’t mean you need to pay a king’s ransom to have your practice valued. Just be sure to speak with the person or firm providing you the appraisal to ensure you have an understanding of the scope of work given your specific purpose.

—R.G.