Journal of Financial Planning: May 2018

Phillip P. Zepp is a Ph.D. student at Kansas State University studying personal financial planning. His research interests involve physiological stress and behavioral finance. Zepp is also a principal analyst at the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA).

Stuart J. Heckman, Ph.D., CFP®, is an assistant professor of personal financial planning in the School of Family Studies and Human Services at Kansas State University. His research focuses on professional financial planning and on financial decisions involving uncertainty, especially among young adults and college students.

Executive Summary

- This study examined the relationship between perceptions of financial future and intertemporal choice by using a new psychological framework—the future self-continuity framework—to investigate intertemporal choices.

- Intertemporal choice is largely based on the concept of temporal discounting. Some individuals can delay immediate gratification with their money for a better financial future. Others prefer immediate gratification, which comes at a cost to their future financial well-being.

- Regression results suggest that perceptions about financial future predict ability to delay gratification. In particular, perceptions about similarity to a person’s financial future and positivity about the performance of the economy may dictate whether clients are willing to delay gratification and save for their future.

- Results also provide evidence that the ability to visualize their financial future and the details of financial goals influence individuals’ willingness to delay gratification.

- Financial planners can use the results of this study to help clients feel connected with their financial future. Increasing the connection between clients and their financial future may help them become more dedicated to reaching their financial goals.

Clients have many different types of financial goals. Typical financial goals include saving for retirement, buying a home, funding a child’s education, and saving for vacation. Although each financial goal is distinct, all have something in common: they require the delay of gratification to reach the goal. When someone delays gratification, they give up something they want today to save for something else in the future. Too often, clients struggle to prioritize their future needs over their present needs (Opiela 2005). As a result, clients are often unable to commit to long-term financial goals (Salsbury 2010), and that can impact the success of the client’s financial future (Birke 2017).

Much of the research on intertemporal choice (i.e., making decisions about how to allocate resources among different time periods) has focused on the process of temporal discounting and the impact of discount rates on financial decision-making and financial behavior (Chabris, Laibson, and Schuldt 2010). Temporal discounting is the process of determining the relative value of rewards at different points in time (Frederick, Loewenstein, and O’Donoghue 2002); the rate at which an individual discounts future rewards is commonly known as an individual’s discount rate. Frederick et al. (2002) found that individuals with high discount rates tend to make decisions based on their desire for immediate gratification, and individuals with low discount rates prefer to delay gratification to obtain a better reward in the future.

From the perspective of maximizing utility, the economic literature suggests that individuals are better off making low-discount choices (Frederick, Loewenstein, and O’Donoghue 2002). Prior research appears to support this position as individuals with lower discount rates typically have better life outcomes: they are more educated, save more, and have better health behaviors (Huston and Finke 2003; Hershfield, Garton, Ballard, Samanez-Larkin, and Knutson 2009; Scharff and Viscusi 2011).

Research also has showed that discount rates are influenced by age, income, overall wealth, education, positions of power, addiction, and uncertainty (Becker and Mulligan 1997; Read and Read 2004; Joshi and Fast 2013). Uncertainty occurs when people make decisions without knowing the probability that an event will occur (Knight 1921). The literature suggests that discount rates are impacted by both internal and external factors; therefore, certain interventions may lower discount rates (Becker and Mulligan 1997).

If client perceptions influence whether they make high- or low-discount choices, an opportunity may exist for financial planners to address the perceptions that influence high-discount choices.

One possible explanation for why clients are unable to prioritize the future over the present comes from the field of psychology. According to the psychology literature, the degree to which people feel connected to their future determines whether they are willing to delay gratification today for the benefit of their future (Hershfield et al. 2009). In some cases, clients may view their financial future as an entirely separate life that they are unable to recognize.

The degree to which people feel connected to their future self is determined, in part, by their perceptions (Hershfield 2011). Client perceptions of their future may determine client willingness to delay gratification for the benefit of their financial future. For example, if clients have positive feelings about life in retirement, they may be more willing to allocate their hard-earned money toward their retirement accounts. If they do not, they may instead indulge in current spending.

Therefore, the purpose of this study is to explore whether people’s perceptions of their financial future influence their intertemporal choice decisions. The results from this study may shed light into the determinants of whether clients are able to delay gratification.

Theoretical Framework

Although intertemporal economic choices have historically been studied through the lens of the discounted utility theory (Frederick, Loewenstein, and O’Donoghue 2002), such models were based on a rational decision-maker who possessed all the available information, evaluated that information, and made a rational decision based on that evaluation. However, the literature suggests that individuals are not stoic and rational decision-makers; rather they use shortcuts, emotion, or partial information to make decisions (Thaler and Shefrin 1981; Loewenstein, Weber, Hsee, and Welch 2001; Opiela 2005; Gigerenzer 2004; Ariely 2008; Kahneman 2011; Kay 2016).

The future self-continuity theory is an emerging psychological framework that incorporates the concept of emotion to explain intertemporal choice decisions (Hershfield 2011). It states that intertemporal choice is influenced by the degree to which individuals are connected to their future self (Hershfield et al. 2009). Recall that psychological connectedness to the future self guides present behavior (Parfit 1971).

Future Self-Continuity Theory

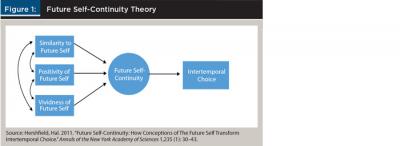

As shown in Figure 1, the future self-continuity theory consists of three primary constructs: (1) similarity to future self; (2) positivity of future self; and (3) vividness of future self (Hershfield 2011). These three constructs measure an individual’s continuity level with the self. Individuals with high self-continuity have high levels of psychological connectedness and low discount rates, resulting in greater likelihood of valuing future needs over present needs and delaying gratification. Conversely, individuals with low self-continuity have low levels of psychological connectedness and high discount rates and are more likely to make decisions that satisfy current needs at the cost of future needs (Hershfield et al. 2009).

Some research has shown that some people view their future self as a completely separate person from their present self at a neurological level (Hershfield 2011). This disconnect causes some people to stop thinking for the future altogether. Indeed, some people are so disconnected from their future self that saving for the future is analogous to a decision between spending money today and giving it to a stranger for the future (Hershfield, Goldstein, Sharpe, Fox, Yeykelis, Carstensen, and Bailenson 2011). Prior research traced this disconnection to specific neurological processes in the brain (Hershfield, Wimmer, and Knutson 2008).

Researchers have used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) machines to evaluate activities in the rostral anterior cingulate cortex (rACC). The rACC is in the frontal cortex of the brain and plays a critical role in high-level brain functions such as complex decision-making, ethical decision-making, and impulse control.

Using fMRI machines, Hershfield, Wimmer, and Knutson (2008) found differences in the activation of the rACC when people made decisions about themselves versus other people, and current self versus future self. When people made decisions about others, the rACC had significantly lower levels of activation. When people made decisions about themselves, the rACC had significantly higher levels of activation. When people thought about their current self, there were significantly higher activations in the rACC when compared to thoughts about the future self. The patterns of activation in the rACC were very similar when people made decisions about other people and thought about their future self.

These results support prior research that suggested a person sometimes views their future self as a completely separate person. When this happens, the person does not access the higher levels of their brain for decision-making. This may explain why people who feel disconnected from their future self do not make low-discount choices even though most people know they need to make optimal decisions for their future.

Similarity to future self. The similarity to future self construct measures the degree to which people feel either similar or dissimilar to their future selves (Hershfield 2011). Low levels of similarity to the future self may influence low self-continuity and high discount rates. Individuals who believe their future self is similar to their present self are more likely to have high self-continuity and low discount rates (Hershfield et al. 2009).

Hershfield et al. (2009) also showed that similarity with the future self influences intertemporal choice. Their experimental study found a significant positive correlation between the similarity of the future self and discount rates. Participants were asked to indicate how connected they felt to their future self of 10 years and were given a series of temporal discounting tasks. The results showed that future self-similarity predicted the number of delayed choices—participants with strong connectedness with their future chose more future rewards than those with a weak connectedness. A separate experimental study by the same authors found that higher future self-similarity scores were correlated with higher levels of accrued assets (Hershfield et al. 2009). These results suggest that the level of similarity with the future self influences intertemporal choice.

Positivity of future self. Positivity of the future self describes how positive people are about their future self. According to Hershfield (2011), people who have positive feelings and thoughts about their future self are more likely to delay present gratification for the benefit of that future self. People who have negative or neutral feelings and thoughts about their future self are more likely to discount the future at higher rates and choose present rewards over future rewards.

Prior research in this area used perceptions of the elderly as a proxy for positivity of future self and found a positive relationship between attitudes toward the elderly and national savings rates (Hershfield and Galinsky 2011), suggesting that positive views about aging and getting older predicts whether people are willing to delay gratification for future rewards.

Vividness of future self. Vividness of the future self describes the extent to which people can visualize their future self. According to Hershfield (2011), when people perceive their future self in a vivid manner, they will delay gratification to allocate current resources to the future self. If people do not perceive their future self in a vivid manner, they may not recognize their future self and feel disconnected. And when people lack vividness of their future self, they will not allocate resources to the future self and instead will prefer immediate gratification.

Prior research that investigated the relationship between vividness of the future self and temporal discounting found that vividness of the future self was a key predictor in determining savings behaviors (Hershfield et al. 2011). Participants in one study were shown age-progressed renderings of themselves and asked to interact with their current self and future self in a virtual environment. At different points throughout the experience, the participants were asked to perform a money allocation task to determine how much they would allocate toward retirement. Those who interacted with their future self in the virtual environment allocated more money toward retirement than those who interacted with their current self (Hershfield et al. 2011).

These findings are consistent with other research that found that when people preferred shorter savings horizons, they saved less than those who preferred longer savings horizons (Fisher and Montalto 2010). One study even found that savings horizons predicted unethical behavior (Hershfield, Cohen, and Thompson 2012). These results suggest that when people prefer the future and can clearly and vividly interact with their future self, they will delay gratification for the benefit of that future self.

Conceptual Framework

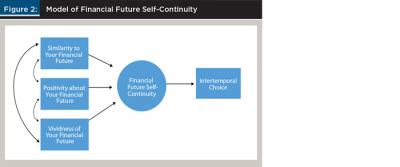

Due to data limitations, this analysis proxied the future self by creating measures of the future financial situation as shown in Figure 2. The rationale was that people who felt strongly connected to the circumstances of their future financial situation were likely to have high levels of future self-continuity. Each of the three primary drivers of future self-continuity (similarity, positivity, and vividness) were conceptualized in relation to the future financial situation and were all expected to be positively related to the financial future self-continuity. Financial future self-continuity was then expected to be related to low-discount choices. Therefore, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H1: The belief that one’s current financial situation and future financial situation are similar will predict low-discount decisions.

H2: A positive outlook on one’s financial future will predict low-discount decisions.

H3: Having a vivid sense of one’s financial future will predict low-discount decisions

Methodology

Data. Data for this analysis came from the 2013 U.S. Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF), a nationally representative cross-sectional survey conducted by the Federal Reserve Board every three years. The purpose of the SCF is to collect in-depth financial information from U.S. households. The 2013 SCF collected financial information from 6,015 households using a complex sample design that oversampled wealthy households and imputed values for missing data.

To address the complex sampling design, Nielsen and Seay (2014) recommended using a bootstrapping technique that adjusts variance estimates to reflect households’ unequal probability of selection. To address the use of imputed values, Lindamood, Hanna, and Bi (2007) recommended using repeated-imputation inference (RII) procedures to obtain more valid estimates of variances and significance levels. Shin and Hanna (2017) recommended using weighted regressions if the goal of the paper is to estimate magnitudes of effects given that weighted regressions produce consistent estimators in regression models. Based on the literature, this study used a weighted regression with RII technique on the full 2013 SCF sample (N = 6,015).

Dependent variable. The dependent variable in this study was intertemporal choice. Based on the literature, five intertemporal choices were analyzed: (1) education; (2) smoking; (3) health status; (4) homeownership; and (5) savings behaviors. Education was coded as a binary variable where 1 = respondent obtained a college degree, and 0 = respondent did not have a college degree. Smoking was coded as a binary variable where 1 = the respondent smoked, and 0 = respondent did not smoke. Health status was self-reported and responses were coded as 4 = excellent, 3 = good, 2 = fair, and 1 = poor. Homeownership was coded as a binary variable where 1 = the respondent owned a home, and 0 = respondent did not own a home. Savings behavior was self-reported and coded as a binary variable where 1 = the respondent had a regular savings plan, and 0 = the respondent did not have a regular savings plan.

Factor analysis and score. Rather than limit the analysis to a single intertemporal choice or use five separate models, the five intertemporal choice variables were combined into one dependent variable. To collapse the five variables into one dependent variable, a factor analysis was performed on one factor. All five intertemporal choice variables were loaded into a confirmatory factor analysis. As indicated in Table 1, the results from the confirmatory factor analysis revealed that each variable loaded on the same axis at above 0.30, which indicated there was a statistically significant correlation between the five variables (Hair, Black, Babin, Anderson, and Tatham 1998). This suggests that the five variables measured the same phenomenon—in this case, intertemporal choice.

With evidence that the five variables were statistically correlated without indeterminacy concerns, the factor was transformed into factor score estimates. A factor score takes a set of variables and standardizes those variables into a single continuous scale (Velicer 1976). The continuous scale can then be used as a singular variable to make relative comparisons.

The five intertemporal choice variables were standardized and transformed into a singular continuous scale that measured the number of low-discount or high-discount choices made by the respondents. For example, when comparing two respondents, a higher factor score estimate indicated that the respondent was relatively more likely to delay gratification for the benefit of their financial future.

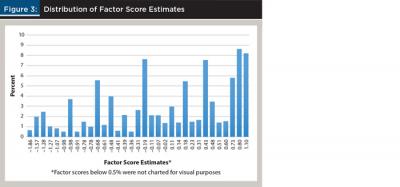

The distribution of factor score estimates is illustrated in Figure 3. The data appears normally distributed and the kurtosis measure indicated acceptable skewness. The mean factor score estimate was zero, the median factor score estimate was 0.10, the minimum factor score estimate was –1.86 and the maximum factor estimate was 1.10. Respondents with a factor score estimate of –1.86 did not have a college degree, smoked, reported a poor health status, did not own a home, and did not have a regular savings plan. Respondents with a factor score estimate of 1.10 had a college degree, did not smoke, reported an excellent health status, owned a home, and had a regular savings plan established.

Independent variables. Basic demographic and financial variables were used as control variables to investigate the impact of the financial future self-continuity. Similarity to financial future was measured with two variables. Variable X7650 in the SCF asked respondents if their current income was unusually high, low, or normal compared to what they would expect in a “normal” year. Variable X7364 asked respondents whether they expected their future income in a year to go up more than inflation, less than, or about the same as inflation.

Positivity about a respondent’s financial future was also measured with two variables. Variable X301 asked respondents whether they expected the U.S. economy over the next five years to perform better, worse, or about the same. Variable X302 asked respondents whether they thought interest rates over the next five years would be higher, lower, or about the same as today.

Vividness of financial future was measured with four variables. Variable X3010 asked respondents if there were any foreseeable major expenses in the next five to 10 years that they expected to pay such as educational expenses, purchase of a new home, health care costs, support for other family members, or anything else. Variable X3008 asked respondents to pick a period that was most important to them when planning or budgeting their family’s saving and spending. Available options were: (1) a few months; (2) next year; (3) next few years; (4) next five to 10 years; and (5) longer than 10 years. Variable X7366 asked respondents to indicate whether they had a good idea of what their family’s income would be next year.

The fourth variable used to measure vividness of financial future was a vivid goal scale. This scale was created from an open-ended question that asked respondents to list the reasons that were most important to them for saving. Respondents could provide as many reasons for saving as they wanted, but following the completion of the interviews, the SCF categorized responses into 36 categories. This analysis reviewed the 36 categories and identified visually specific goals as those involving tangible reasons to save. Examples of visually specific goals included funding education, weddings or other ceremonies, buying a home, home improvements, and vacations. The remaining 22 categories were identified as non-visually specific goals that involved generic reasons to save such as “like to save,” “to get ahead,” “investment reasons,” and “living expenses.” The number of visually specific goals provided by each respondent was then summed and used as a simple additive scale. For example, if a respondent provided three visually specific goals for saving, the respondent received a score of three.

Statistical Analysis

Factor score estimates of intertemporal choices were used as a continuous dependent variable in a two-block hierarchal regression analysis. In the first step, the factor score estimate was regressed onto a vector of control variables, and in the second step, the future financial self-continuity variables were added to the regression.

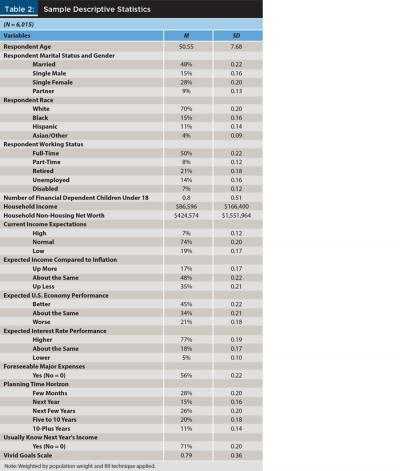

Control variables included respondent age, respondent race, respondent working status, number of financially dependent children under age 18 living in the household, household income, and household non-housing net worth. Sample descriptive statistics are shown in Table 2. As suggested by prior research, RII and bootstrapping techniques were used to address the use of multiple implicates and complex sampling design (Lindamood, Hanna, and Bi 2007; Nielsen and Seay 2014).

Results

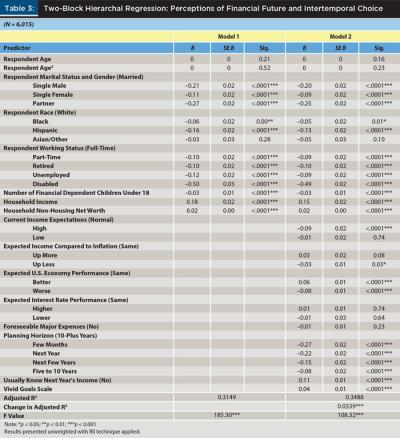

The results from the initial regression that only used the demographic and financial control variables (Model 1) were consistent with the literature (Becker and Mulligan 1997). Married couples had statistically significantly higher factor score estimates when compared to single men, single females, and partnered couples. White respondents had statistically significantly higher factor score estimates when compared to Black, Hispanic, and Asian respondents. Respondents who worked full-time had statistically significantly higher factor score estimates when compared to respondents who were part-time, retired, unemployed, or disabled. Households with financially dependent children under the age of 18 had statistically significantly lower factor score estimates. Consistent with the literature, household income and household non-housing net worth was positively significant in the model (Becker and Mulligan 1997). These demographic and financial control variables produced an adjusted R2 of 0.3149, which means that these variables explained 31.49 percent of the factor score estimates.

Model 2 retained the demographic and financial control variables and added in the perception variables that measured financial future self-continuity (see Table 3). The addition of the perception variables increased the explained variance in the factor score estimates from 0.3149 to 0.3488. The addition of the perception variables in Model 2 was statistically significant and increased the modeling power to 34.88 percent (F30,5984 = 10.36, p < 0.001) (Raudenbush and Bryk 2002; Soper 2017). This provides evidence that it is important to account for people’s perceptions of their financial future when predicting whether they will delay gratification or prefer immediate gratification.

Similarity to financial future. The two variables used to measure similarity to your financial future were both statistically significant, although the results were somewhat unexpected. When compared to respondents who found their current income to be normal as expected, respondents who found their income to be unusually higher than expected had lower factor score estimates. (There was no statistical difference in factor score estimates between respondents who found their income to be normal versus those who found it low.)

When compared to respondents who believed their income would rise at the same rate as inflation, respondents who thought that inflation would outpace their income had statistically lower factor score estimates. (There was no statistical difference in factor score estimates between respondents who thought their income would rise at the same rate as inflation and respondents who thought their income would outpace inflation.)

Positivity of financial future. Only one variable used to measure positivity of financial future was statistically significant in the model. As expected, when compared to the respondents who believed the performance of the U.S. economy would remain the same, respondents who thought the economy would perform better had statistically higher factor score estimates. Conversely, when compared to the respondents who believed the performance of the U.S. economy would remain the same, respondents who thought the economy would perform worse had statistically lower factor score estimates.

For the expected interest rate performance variable, there was no statistical difference among the respondents when the “same” answer was used as the reference group. The reason for the non-significance of this variable may be because it is difficult to ascertain whether higher interest rates, lower interest rates, or flat interest rates are “better” or “worse” for each respondent. Two different respondents could indicate they believed interest rates would rise and one could be a positive answer and the other a negative answer.

Vividness of financial future. Three of the four variables used to measure vividness of financial future were statistically significant in the model. The ability to foresee major expenses within the next five to 10 years was not statistically significant in the model. As expected, respondents who indicated that 10-plus years was the most important time frame for planning and budgeting had statistically higher factor score estimates. The factor score estimates moved increasingly lower for each descending time period. When comparing the two polar time frames of 10-plus years and next few months, respondents who indicated that the next few months was the most important time frame had 0.27 lower factor score estimates. Even after standardizing the beta coefficients, this was the largest coefficient among the financial future self-continuity variables.

Respondents who usually knew how much their income would be in the following year had statistically higher factor score estimates. This result was expected given that it may be difficult to delay gratification if respondents do not know how much income they will have in a year. Finally, the vivid goals scale was also statistically significant in the model. For every vivid goal that was provided by the respondent, their factor score estimate increased by 0.04. Therefore, if a respondent provided three visually specific goals, their factor estimate was 0.12 higher than the respondent who did not provide any visually specific goals.

Discussion and Implications for Planners

Delaying gratification and making low-discount choices is an important concept in financial planning. If clients are going to achieve long-term financial goals, they need to be willing to allocate current resources towards their future. This study applied a new psychological framework—the future self-continuity framework—to investigate intertemporal choices.

The results from this study suggest that client perceptions about their financial future predict their choices. Specifically, people who had positive expectations for the performance of the U.S. economy delayed gratification at a higher rate than those who had negative expectations. For financial planners, this means that it may be beneficial to monitor client perceptions about the economy as well as perceptions about individual account performance.

Although this study did not include perceptions about individual account performance, it is possible that negative perceptions regarding the performance of their own accounts may present a barrier for saving. Clients may not be willing to allocate their hard-earned money toward a future that elicits negative perceptions.

Clients may also be unwilling to carry out action items or other steps critical to the financial plan if they have negative feelings about the direction of their financial future. This means that planners should keep a close eye on their client’s perceptions and perhaps survey them when they come into the office to make sure they are feeling positive about their financial future. If planners can identify negative perceptions, it may present an opportunity to address them. Addressing and altering the perceptions may increase the likelihood that clients carry out the financial plan or action items.

Results from the similarity of financial future construct were mixed. People who had unusually high income compared to what was expected delayed gratification at a lower rate compared to those who expected normal income. This was, perhaps, an unexpected result, given that a surplus of income is usually a positive outcome. Based on this finding, it is recommended that planners consider setting up a plan of action ahead of time for non-normal income. For example, helping clients establish an agreement with themselves that a pre-determined portion of any unexpected income will be saved for a particular goal may strengthen the client’s ability to follow through and lower the temptation to spend that money.

Respondents who expected their income to lose purchasing power (go up less than inflation) delayed gratification at a lower rate compared to those who expected to maintain the same purchasing power with their income. This result was consistent with the theoretical expectation that people with a dissimilar financial future would delay gratification at a lower rate. Due to limited measures available in the dataset, purchasing power expectations could measure the respondent’s positivity about their financial future rather than the similarity to their financial future. However, these results still suggest that expectations about future income can predict client choices. Specifically, when people receive a surplus of unexpected income, they spend that money on immediate gratification. When faced with expected losses in purchasing power, people prefer immediate gratification.

In addition to the similarity and positivity of financial future constructs, the vividness of financial future construct also produced some interesting results. In particular, the planning and budgeting time period variable was the strongest predictor of intertemporal choice as measured by beta coefficient size. These results were consistent with previous literature, as respondents with longer planning periods had higher factor score estimates (Fisher and Montalto 2010). One possible explanation for these results is that some people do not instinctively think about the long term, and this impacts their ability to delay gratification for the benefit of their future. Another possible explanation for these results is that some people do not have a clear sense of their financial future, so they prefer shorter time periods that are easier to visualize. Those without a vivid picture of their cash flows may be disconnected from their financial future and therefore choose immediate gratification with their money.

The results on the vivid goal scale suggest that the ability to visualize and specify goals positively influences whether people delay gratification. This result is especially relevant given that client financial goals are the catalyst for decisions made during the financial planning process. If clients are giving generic reasons to save, this may be a red flag that they cannot visualize their goals and feel disconnected from their financial future. When planners meet with clients to discuss financial goals, it may be beneficial for clients to discuss their goals in greater detail. Planners can encourage clients to be specific in describing retirement and can ask clients to walk through their ideal day in retirement. Although this may seem unnecessary and perhaps a bit awkward, this process can help clients visualize their goals so that they are more willing to delay gratification in the present for the benefit of reaching this goal in the future. Planners should also consider customizing paperwork so that the written financial plan references the specific details of the client’s financial goals.

Conclusion

The results from this study were largely consistent with the previously cited literature (Hershfield 2011). Similarity, positivity, and vividness of one’s financial future appears to predict intertemporal choices. For planners, the results highlight the importance of exploring whether their clients feel connected to their financial future. If clients are showing signs that they are not connected with their financial future, they may not be in the right frame of mind to delay gratification with their income for the benefit of their financial future.

Planners should ensure that clients feel like their current financial situation and future financial situation are similar. If there is a dissimilar relationship between the two, clients may feel disconnected from their financial future. Planners should also check in with clients to make sure they have a positive attitude about the direction of their financial future, including ancillary indicators such as the expected performance of the economy. If clients do not have positive perceptions, they may feel disconnected from their financial future.

Lastly, planners should illicit as many details as possible when clients discuss their goals. Extracting specific details that paint a vivid picture of a client’s financial future may help increase future self-continuity, which impacts whether the client is willing to delay gratification by deferring the use of current resources for the benefit of their future self.

References

Ariely, Dan. 2008. Predictably Irrational: The Hidden Forces That Shape Our Decisions, First Edition. New York, N.Y.: HarperCollins Publishers.

Becker, Gary S., and Casey B. Mulligan. 1997. “The Endogenous Determination of Time Preference.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 112 (3): 729–758.

Birke, Kol. 2017. “The Science of Helping Clients Change.” Journal of Financial Planning 30 (5): 25–27.

Chabris, Christopher F., David I. Laibson, and Jonathon P. Schuldt. 2010. “Intertemporal Choice.” Behavioural and Experimental Economics 1 (1): 168–177.

Fisher, Patti J., and Catherine P. Montalto. 2010. “Effect of Saving Motives and Horizon on Saving Behaviors.” Journal of Economic Psychology 31 (1): 92–105.

Frederick, Shane, George Loewenstein, and Ted O’Donoghue. 2002. “Time Discounting and Time Preference: A Critical Review.” Journal of Economic Literature 40 (2): 351–401.

Gigerenzer, Gerd. 2004. “Fast and Frugal Heuristics: The Tools of Bounded Rationality.” In Blackwell Handbook of Judgment and Decision Making, edited by Derek J. Koehler and Nigel Harvey, 62–88, First Edition. Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

Hair, Joseph F., William C. Black, Barry J. Babin, Rolph E. Anderson, and Ronald L. Tatham. 1998. Multivariate Data Analysis, Fifth Edition. Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Prentice Hall.

Hershfield, Hal. 2011. “Future Self-Continuity: How Conceptions of The Future Self Transform Intertemporal Choice.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1235 (1): 30–43.

Hershfield, Hal, and A. D. Galinsky. 2011. “Respect for the Elderly Predicts National Savings and Individual Saving Decisions.” Evanston, IL: Northwestern University.

Hershfield, Hal, Daniel G. Goldstein, William F. Sharpe, Jesse Fox, Leo Yeykelis, Laura L. Carstensen, and Jeremy N. Bailenson. 2011. “Increasing Saving Behavior Through Age-Progressed Renderings of the Future Self.” Journal of Marketing Research 48 (SPL): S23–S37.

Hershfield, Hal, G. Elliott Wimmer, and Brian Knutson. 2008. “Saving for the Future Self: Neural Measures of Future Self-Continuity Predict Temporal Discounting.” Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience 4 (1): 85–92.

Hershfield, Hal, M. Tess Garton, Kacey Ballard, Gregory R. Samanez-Larkin, and Brian Knutson. 2009. “Don’t Stop Thinking About Tomorrow: Individual Differences in Future Self-Continuity Account for Saving.” Judgment and Decision Making 4 (4): 280–286.

Hershfield, Hal, Taya R. Cohen, and Leigh Thompson. 2012. “Short Horizons and Tempting Situations: Lack of Continuity to Our Future Selves Leads to Unethical Decision Making and Behavior.” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 117 (2): 298–310.

Huston, Sandra J., and Michael S. Finke. 2003. “Diet Choice and the Role of Time Preference. Journal of Consumer Affairs 37 (1): 143–160.

Joshi, Priyanka D., and Nathanael J. Fast. 2013. “Power and Reduced Temporal Discounting.” Psychological Science 24 (4): 432–438.

Kahneman, Daniel. 2011. Thinking, Fast and Slow, First Edition. New York, N.Y.: Macmillan.

Kay, Barbara. 2016. “From Irrational to Rational: 6 Steps to Guide Clients to Productive Decisions.” Journal of Financial Planning 29 (6): 28–30.

Knight, Frank. 1921. Risk, Uncertainty, and Profit. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Co.

Lindamood, Suzanne, Sherman D. Hanna, and Lan Bi. 2007. “Using the Survey of Consumer Finances: Some Methodological Considerations and Issues.” Journal of Consumer Affairs 41 (2): 195–222.

Loewenstein, George F., Elke U. Weber, Christopher K. Hsee, and Ned Welch. 2001. “Risk as Feelings.” Psychological Bulletin 127 (2): 267–286.

Nielsen, Robert B., and Martin C. Seay. 2014. “Complex Samples and Regression-Based Inference: Considerations for Consumer Researchers.” Journal of Consumer Affairs 48

(3): 603–619.

Opiela, Nancy. 2005. “Rational Investing Despite Irrational Behaviors.” Journal of Financial Planning 18 (1): 34–42.

Parfit, Derek. 1971. “Personal Identity”. Philosophical Review 80 (1): 3–27.

Raudenbush, Stephen, and Anthony Bryk. 2002. Hierarchical Linear Models, Second Edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Read, Daniel, and Nicoleta Liliana Read. 2004. “Time Discounting Over the Lifespan.” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 94 (1): 22–32.

Salsbury, Gregory. 2010. “The Psychology of Retirement Planning: How to Help Your Clients Avoid Common Mistakes and Modify Bad Behavior.” Journal of Financial Planning 23 (7): 44–47.

Scharff, Robert L., and W. Kip Viscusi. 2011. “Heterogeneous Rates of Time Preference and the Decision to Smoke.” Economic Inquiry 49 (4): 959–972.

Shin, Su Hyun, and Sherman D. Hanna. 2017. “Accounting for Complex Sample Designs in Analyses of the Survey of Consumer Finances.” Journal of Consumer Affairs 51 (2): 433–447.

Soper, Daniel. 2017. “F-Value Calculator for Hierarchical Multiple Regression [software].” Available from danielsoper.com/statcalc.

Thaler, Richard H., and Hersh M. Shefrin. 1981. “An Economic Theory of Self-Control.” Journal of Political Economy 89 (2): 392–406.

Velicer, Wayne F. 1976. “The Relation Between Factor Score Estimates, Image Scores, and Principal Component Scores.” Educational and Psychological Measurement 36 (1): 149–159.

Citation

Zepp, Phillip P., and Stuart J. Heckman. 2018. “Clients’ Perceptions of Their Financial Futures Predict Choices.” Journal of Financial Planning 31 (5): 38–47.