Journal of Financial Planning: March 2021

NOTE: Click or tap on the Tables below for a PDF version of the image.

JOIN THE DISCUSSION: Discuss this article with fellow FPA Members through FPA's Knowledge Circles.

FEEDBACK: If you have any questions or comments on this article, please contact the editor HERE.

What do financial planners and mediators have in common? At first glance, it would appear the answer is nothing.

Financial planners advise individuals, couples, families, business owners, and corporations to help them meet their long-term financial objectives. Mediators facilitate dialogue between two or more parties to help them reach an agreement. That is what financial planners and mediators do. But if you consider why clients hire each of these professionals—and also consider the skillset required by both in order to be successful—you will find striking similarities.

Clients hire financial planners and mediators for the same reason: to help them identify their goals and design a path to achieve them. In order to best serve their clients, both professionals must fully understand their clients’ needs, interests, fears, and priorities. Successful financial planners—just like successful mediators—are experts at connecting with clients and establishing rapport and trust. For some people, this comes naturally. For others, it is a learning process.

This article focuses on three cornerstone mediation techniques financial planners can learn and use with clients. Incorporating these powerful communication tools into your financial planning practice will strengthen your relationships with clients, deepen your insights about who your clients are as you analyze their financial options, and enable you to skillfully facilitate challenging conversations about money.

Active Listening

One of the hardest skills to master is the art of active listening. We easily become distracted by our thoughts, quickly focus on formulating a response before the other person has finished speaking, and rarely make an effort to intentionally listen when someone is talking. Active listening means concentrating exclusively on what is being communicated rather than passively hearing the message of the speaker. It is an essential component of effective communication.

Active listening involves:

- Slowing down and leaving room for silence.

- Listening to understand, learn, and obtain information.

- Heightened self-awareness and management of biases.

- Being fully present in the conversation.

- Giving full attention to the speaker.

- Listening with all senses.

- Noticing non-verbal cues such as facial expressions, tone, posture, and gestures.

- Reflecting back what is being heard to communicate understanding or to clear up misunderstanding.

- Asking clarifying questions to let the speaker know that you have heard them and to seek feedback about the accuracy of what you have heard.

While this may seem simple, it is easier said than done. One way to gain insight into the degree to which you are actively listening in your daily life is to notice, during all your interactions, the extent to which you are truly present. Do you feel connected and engaged with the speaker or is your mind wandering as you formulate your response before the speaker has finished their thought? Are you noticing non-verbal cues or are you focused solely on the speaker’s words? Are you genuinely curious about what you are hearing or are you drawing conclusions, making assumptions, and judging the message? The more we practice active listening in our daily lives, the more it becomes our natural way of engaging with others.

Asking Open-Ended Questions

Open-ended questions prompt deeper conversations. They enlarge the window into a client’s needs, interests, fears, and priorities. Mediators are trained to ask open-ended questions to uncover needs and interests that underlie a client’s stated positions. This is important in any conflict-resolution process because focusing on needs and interests—rather than on positions—shifts the conversation from battle to understanding, and eventually to brainstorming options. In other words, positions contract possibilities, while needs and interests expand them.

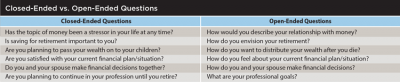

Closed-ended questions elicit “yes” or “no” answers. They typically begin with “can,” “did,” “will,” “was,” “does,” “are,” or “has.” By design, closed-ended questions limit the information the responder can provide. Worse, closed-ended questions run the risk of biasing the responder by suggesting a particular answer, which may influence the answer to the question. Of course, there are times when it is useful to ask a closed-ended question (e.g., as a tool to segue to a new topic or when seeking quantitative rather qualitative information). Most of the time, a closed-ended question should be followed up with an open-ended question in order to keep the dialogue open and informative.

Open-ended questions begin with words such as “how,” “what,” “when,” “where,” “who,” and “why.” Note that asking “why” questions should be used sparingly and skillfully. These types of questions can be received by a client as judgment or bias based, thereby influencing how the question is answered and potentially leading the client to feel that the professional does not understand or respect them. When using a “why” question, it is important to make sure it is asked with genuine curiosity and that it is devoid of judgment or bias.

Asking open-ended questions is a powerful tool to let the client know the professional they are working with is interested in them and is eager to learn more about who they are, what’s important to them, and what concerns them. It creates a smooth and open communication flow based on curiosity, openness, and non-judgment.

To illustrate this, consider the comparison of closed-ended questions and open-ended questions listed on the next page. Both types of questions seek to elicit information about a particular topic. Imagine how each question might be received by a client. Does the question invite an expansive response and communicate interest in getting to know, understand, and connect with the client—or does the question elicit short answers, create choppy flow, and make the client wonder if they are being judged and expected to answer the question a particular way?

Asking open-ended questions is an essential tool to fully and holistically understand your client, their history, life vision, regrets, fears, successes, priorities, passions, needs, and interests. Together, open-ended questions and active listening build trust, rapport, mutual understanding, and respect.

Reframing

Another tool in the mediator’s toolbox is reframing. Reframing creates a new context or perspective about a given situation. Reframing helps a person who is ensnared in negative thoughts and beliefs move toward the positive outcome they want to achieve. It also expands thinking, shifts focus from the past to the future, increases available options, uncovers underlying interests beneath positions, and identifies common concerns and goals. Some examples of when mediators use reframing is when one or more parties are stuck in negative narratives, feeling powerless and hopeless, grasping hard onto their positions, and conflict is rising.

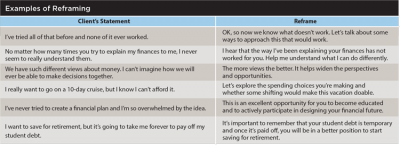

Reframing is a technique where the mediator rewords or restates what the client has said more constructively. It assists the client in understanding their thoughts, reevaluating their perspective, and clarifying what is important to them. When working with two or more people who are engaged in a challenging conversation, reframing can also help de-escalate the conflict.

Financial planners should consider using this powerful tool with individual clients who are having difficulty making financial decisions or who are assuming the worst outcome no matter how many options the financial planner presents. It is also an effective tool when working with couples who are experiencing negative interactions or unproductive decision-making patterns during meetings, and with business owners who are entrenched in their positions and struggling to listen to one another.

Some examples of reframing statements are set forth in the chart on the previous page.

No one is born a skillful communicator. Expert communication must be learned and practiced, just like any other skill. Because financial planning is driven entirely by the personal and business needs and interests of the client, knowing how to connect and communicate effectively with clients is equally important, if not more important, than a financial planner’s training, expertise, and experience. The techniques described in this article are foundational techniques used by mediators to create opportunities for listening, understanding, and deepening connection—the same ingredients necessary for strengthening and sustaining financial planners’ relationships with clients. In the end, it turns out mediators and financial planners do have quite a bit in common.

Rachel B. Goldman, J.D., CPC, ELI-MP, is a lawyer, mediator, communication coach, trainer, and facilitator of difficult conversations. Her clients include executive and emerging leaders, clergy and lay leaders, attorneys, organizational teams and committees, professional groups, and family members. She founded RBG Consulting to teach and promote constructive ways to communicate, manage conflict, and embrace differences in the workplace, in one’s personal life, and within communities. Goldman recently designed and taught a half-day implicit bias workshop for the FPA Massachusetts chapter.