Journal of Financial Planning: June 2019

Greg Geisler, Ph.D., is a clinical professor of accounting at Indiana University—Bloomington. His work has been published in many journals, including four other articles in the Journal of Financial Planning. He is the 2017 recipient of the Journal’s Montgomery-Warschauer Award.

Dawn Drnevich, Ph.D., is a visiting assistant professor of accounting at Indiana University—Bloomington. Her work has been presented at several conferences and published in many refereed journals. Prior to academia, she worked in both public accounting and private industry as a tax consultant.

Executive Summary

- Beginning in 2018, a new deduction under IRC §199A of up to 20 percent of qualified business income for individual owners of business entities taxed as S corporations, partnerships, and sole proprietorships came into law. This new deduction is meant to “compensate” business owners for not operating as C corporations, which saw their federal income tax rate drop to 21 percent beginning in 2018.

- This new deduction, however, is phased out for specified service trades or businesses (SSTBs), generally professional service businesses, based on the individual owner’s taxable income.

- For example, in 2019, the start of the phase-out range for a married couple filing a joint tax return is when their taxable income before the QBI deduction exceeds $321,400, and this deduction is completely phased out when taxable income reaches $421,400.

- This paper discusses the importance of tax planning for those who may be affected by this phase-out because of the high effective federal marginal tax rates impacting an individual owner of an SSTB.

Abbreviations

EffFedMTR: Effective federal marginal income tax rate

SSTB: Specified service trade or business

STR: Statutory federal income tax rate

TIpreQBIded: Taxable income before the qualified business income deduction

In December 2017, President Trump signed into law the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. It created a new deduction (IRC §199A) for taxpayers with qualified business income—the income earned by S corporations, partnerships, sole proprietors, and LLCs if taxed as one of these three types of businesses; in other words, businesses where all of the activity “passes through” to the owners’ tax returns (Gardner and Daff 2018; and Welch and Gardner 2018). Often, but not always, it grants a 20 percent deduction of qualified business income, or QBI, for such taxpayers. This deduction reduces taxable income as opposed to an above-the-line (before adjusted gross income) deduction, which reduces gross income, or an itemized deduction, which reduces taxable income only to the extent the total exceeds the standard deduction. This new deduction applies for income tax purposes and does not affect the calculation of self-employment taxes, which many such taxpayers also must pay.

A special provision exists for specified service trades or businesses (SSTBs)—which is the focus of this paper—where either some or all of the deduction is phased out as taxable income before this QBI deduction exceeds threshold amounts. Specifically, for 2019, if a taxpayer’s taxable income before the qualified business income deduction (abbreviated in this paper as TIpre-

QBIded) is greater than $321,400 for those married filing jointly ($160,700 for single and head-of-household filing statuses), then the QBI deduction is phased out over the next $100,000 for married filing jointly (MFJ), or $50,000 for single and head of household.1

The deduction is completely phased out for taxable income greater than $421,400 for MFJ ($210,700 for single and head of household). Generally, the effect of the SSTB phase-out for an individual taxpayer is to reduce the QBI deduction by 5 percent for each $5,000 of income for MFJ ($2,500 for single and head of household) that TIpre-

QBIded exceeds $321,400 ($160,700 for single or head of household). For those married filing separately, the phase-out begins at $160,725. Given this filing status is not as common, single and head-of-household filing statuses are focused on in this paper.

It is uncommon for a financial planning business to be a C corporation. According to the new tax law, such businesses that are not C corporations are SSTBs. As a result, many financial planning business owners will be subject to the phase-out of some, or all, of their QBI deduction. Over the range where the QBI deduction is phased out, the owner’s effective federal marginal tax rate (abbreviated here as EffFedMTR) is significantly higher than their statutory federal income tax rate (STR) bracket—which will be shown later in this paper. In this paper, EffFedMTR is defined as the increase in tax on an increase in non-QBI income of $100, whereas the STR bracket refers to the federal income tax rate schedule’s row (or bracket) that the individual taxpayer’s taxable income places them in. The former rate is the same as the latter rate if the individual taxpayer is not inside a phase-out range. The EffFedMTR is higher than the STR if the individual taxpayer is inside a phase-out range.

An owner of an SSTB with expected income inside or above the phase-out range has a potential opportunity to do tax planning to obtain the maximum amount of the QBI deduction. This paper specifically addresses the considerations for tax planning from both the individual- and business entity-level perspectives to maximize the QBI deduction. The incentives to reduce TIpre-QBIded, such as by increasing retirement contributions, increasing health savings account contributions, income planning to bunch itemized deductions in specific years, and entity considerations for deferring income and accelerating deductions such as depreciation are discussed. With careful tax planning, taxpayers can reduce their tax burden through either limiting or eliminating the phase-out of this new deduction.

The remainder of this paper discusses IRC §199A, providing the intent of the deduction and the terminology with respect to the key considerations in the legislation, including who qualifies, the phase-out, and wage and property limits. This is followed by a discussion of the tax considerations for individual owners of SSTBs where exceeding the beginning of the threshold amount is either likely or certain. Then several examples are provided using the effective federal marginal tax rates to illustrate the tax consequences of being in the SSTB phase-out range. The importance of tax planning and the key aspects to consider as a result of the new deduction are discussed.

Understanding Section 199A

The provision in IRC §199A grants a special deduction for qualified business income for certain taxpayers and can effectively reduce the top marginal rate by 20 percent for qualified business income. Given the reduction in the corporate tax rate to a flat 21 percent, the intent of §199A is to create a more level playing field for other entities (i.e., businesses that are not C corporations) by lowering the effective tax rate on qualified business income. A qualified business is considered a sole proprietor, partnership, S corporation, and limited liability company (LLC) with pass-through income, but does not include employees, C corporations, and SSTBs.

According to IRC §1202(e)(3)(A), SSTBs include businesses that perform services in certain fields including health, law, accounting, actuarial science, financial or brokerage services, consulting, performing arts, and athletics. Engineering and architecture firms are excluded from this definition and are not considered an SSTB.2 In contrast, financial planning businesses that are not C corporations are considered SSTBs.

The QBI deduction is allowed and SSTBs are considered qualified businesses if TIpreQBIded does not exceed the level at which the phase-out threshold begins. Recall that the QBI deduction is phased out based on the taxpayers’ TIpreQBIded between the range of $321,400 and $421,400 for MFJ ($160,700 to $210,700 for other filing statuses). Therefore, for taxpayers within the phase-out range, the deduction is phased out over a $100,000 range for MFJ ($50,000 for other filing statuses).

The definition of QBI includes trade or business income connected to the conduct of business in the United States and includes income, gains, deductions, and losses. It does not include investment-related items of the business, reasonable compensation paid to an S corporation shareholder, or guaranteed payments to partners for services provided to the business. Generally, the QBI deduction is the lesser of: (1) 20 percent of qualified trade or business income; or (2) 20 percent of TIpreQBIded, which is taxable income (in excess of net capital gain income and qualified dividend income) before this deduction.

The QBI deduction, for both SSTBs and non-SSTBs, is potentially limited based on W-2 wages paid and depreciable (not real) property used in the business, but only when the TIpreQBIded meets certain thresholds. Specifically, the wage and property limitation does not apply to individual taxpayers whose TIpreQBIded is below the threshold where this potential limitation begins to apply ($321,400 for MFJ or $160,700 for other statuses).

To determine whether the wage and property limitation applies or not, the business owner uses the greater of: (1) 50 percent of the W-2 wages for the qualified trade or business; or (2) the sum of 25 percent of the W-2 wages plus 2.5 percent of the unadjusted basis of qualified property immediately after acquisition (i.e., generally depreciable tangible personal property—which does not include real estate). The wage and property limitation must be completely considered by taxpayers whose TIpre-

QBIded is above where the potential limitation fully applies ($421,400 for MFJ or $210,700 for other statuses). For those taxpayers in between where this limit begins to apply and where it fully applies, a pro-rated portion of the W-2 wage and qualified property limitation applies based on the taxable income over the beginning threshold amount, taking into consideration the phase-out range (TIpreQBIded less the threshold beginning amount [$321,400 for MFJ/$160,700 for other statuses] divided by the threshold range [$100,000 for MFJ/$50,000 for other statuses]).

To summarize, for non-SSTBs, the wage and property limitation partially applies when TIpreQBIded is in excess of $321,400 for MFJ ($160,700 for other statuses) and fully applies when TIpreQBIded is in excess of $421,400 ($210,700 for other statuses). The wage and property limitation can reduce the otherwise allowable QBI deduction for non-SSTB business owners.

In contrast, for SSTBs, the wage and property limitation must be applied with TIpreQBIded in excess of $321,400 for MFJ ($160,700 for other statuses) and less than $421,400 ($210,700 for other statuses) to see if it further reduces the partially phased-out QBI deduction. For SSTBs, the wage and property limitation is irrelevant when TIpreQBIded reaches or exceeds $421,400 ($210,700 for other statuses), since the QBI deduction is fully phased out (equals $0). It is possible that both the wage and property limitation and the SSTB phase-out apply. For simplicity, however, the analysis here assumed that 50 percent of the W-2 wages to employees were large enough that they did not limit the QBI deduction.

When Taxable Income Falls Within the Phase-Out Range

When an individual owns an SSTB and has TIpreQBIded in the phase-out range, two things happen simultaneously when TIpreQBIded increases: the additional income and the reduced QBI deduction increase taxable income, which increases the federal income tax by a larger amount than the impact from just the additional income alone.

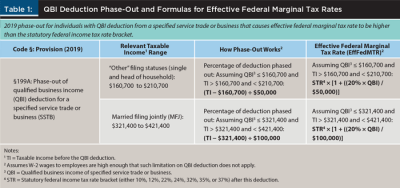

For example, assume an owner who is married filing jointly has QBI of $321,400 and the TIpreQBIded ranges from $321,400 to $421,400. At either end of the TIpreQBIded range, the QBI deduction is $64,280 (20 percent of $321,400 QBI) in the former case ($321,400), and $0 in the latter case ($421,400). In the former case, taxable income after the QBI deduction is $257,120 ($321,400 TIpreQBIded minus $64,280 QBI deduction). In the latter case, taxable income is $421,400, because the QBI deduction is $0. To generalize these facts from the two extreme cases to any case where TIpreQBIded is greater than $321,400 but less than $421,400, see Table 1.

Table 1 provides the percentage of the QBI deduction phased out (third column) and the formula for the effective federal marginal tax rate (EffFedMTR) (fourth column). Given a constant amount of QBI and TIpreQBIded in the phase-out range, taxable income after the QBI deduction can place the taxpayer in the 24 percent, 32 percent, or 35 percent STR bracket. The EffFedMTR can be one of three rates: 39.43 percent, 52.57 percent, and 57.50 percent, respectively, if QBI equals $321,400 and taxpayers are married filing jointly.3 The EffFedMTRs are higher than the STR bracket given that TIpreQBIded is in the phase-out range. These EffFedMTRs are from the formula at the end of the fourth column of Table 1 shown below:

STR × [1 + ((20% × QBI) / $100,000)] = STR × [1 + ((20% × $321,400) / $100,000)] =

STR × [1 + ($64,280 / $100,000)] = 24% or 32% or 35% × 1.6428 = 39.43% or 52.57% or 57.50%, respectively.

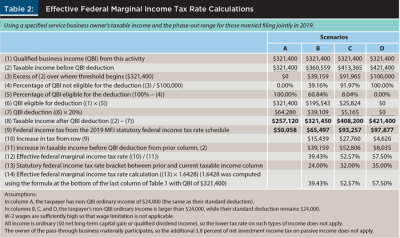

Examples of the EffFedMTR formula for different scenarios are shown in Table 2.

Assuming TIpreQBIded is inside the SSTB phase-out range and is either $360,559 (line 2 of column B in Table 2) or $413,365 (line 2, column C), the QBI deduction is $39,109 (line 7, column B) in the former case and $5,165 (line 7, column C) in the latter case. In the former case, taxable income (line 8, column B) is $321,450, which is the top of the 24 percent STR bracket, and in the latter case, taxable income (line 8, column C) is $408,200, which is the top of the 32 percent bracket.

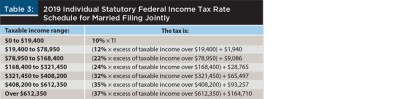

Table 3 contains the statutory federal income tax rate brackets (see the seven rates, in bold, ranging from 10 percent to 37 percent).

The EffFedMTR is 39.43 percent (line 12, column B of Table 2) as taxable income increases above $257,120 up to $321,450 (line 8, columns A and B of Table 2). The reason for the high EffFedMTR is the phase-out of some of the $64,280 QBI deduction (line 7, column A versus column B).

Next, when taxable income gets above $321,450 and before it reaches $408,200, the taxpayer is in the 32 percent STR bracket and the taxpayer’s EffFedMTR is 52.57 percent (line 12, column C of Table 2). Finally, when taxable income gets above $408,200 and before it reaches $421,400, the taxpayer is in the 35 percent tax rate bracket and the taxpayer’s EffFedMTR is 57.50 percent (line 12, column D). Note that when taxable income exceeds $421,400 but does not exceed $612,350, the taxpayer is still in the 35 percent STR bracket, and $100 of income increases taxable income by $100, because the QBI deduction has already been fully phased out, and the EffFedMTR returns to be the same as the STR bracket, 35 percent.

To summarize Table 2’s column A compared with column D, assuming QBI equals $321,400 for an MFJ taxpayer and TIpreQBIded increases $100,000 from $321,400 to $421,400, the taxpayers pay $47,819 more tax (line 9, last column minus first column [$97,877 − $50,058]). A $47,819 increase in tax on an increase in non-QBI income of $100,000 is a 47.82 percent EffFedMTR. This rate is a blend of the three EffFedMTRs of 39.43 percent, 52.57 percent, and 57.50 percent (line 12, columns B, C, and D, respectively). Because the effective rate of tax inside the phase-out range for an SSTB is so high, it is referred to here as the “SSTB tax torpedo.”

Tax-Planning Considerations

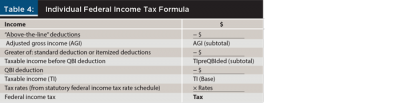

The high EffFedMTRs while inside the QBI deduction phase-out range for SSTBs demonstrate the importance of tax planning; such planning can either increase or fully restore the QBI deduction. The federal individual tax formula is given in Table 4.

With most individual phase-outs in the federal income tax law, generally, the only tax-planning opportunities available to increase the tax break (i.e., reduce the impact of the phase-out) are those that reduce AGI. The QBI deduction, however, uses taxable income, so tax planning that reduces TIpreQBIded can increase the QBI deduction.

Therefore, it is not only strategies that reduce AGI, but also those that increase itemized deductions above the standard deduction that are effective for increasing the QBI deduction. The importance of this difference cannot be overstated, especially for financial planners, as there are more opportunities created by adding in tax planning for itemized deductions. There are more ways to reduce TIpreQBIded than there are to reduce AGI.

The importance of tax planning and the key aspects to consider as a result of the new QBI deduction include considerations from both the individual and business entity-level perspectives to maximize the deduction. If, before the end of 2019, it appears that the QBI deduction is going to be either eliminated or reduced, then generally the proper strategy is to accelerate deductions into the current year or defer income to a later year.

Strategies for individuals. Specific opportunities to reduce TIpreQBIded by reducing AGI for individual taxpayers include the following:

- Increasing tax-deferred retirement contributions to employer-sponsored plans (for example, a 401(k) plan has a $19,000 maximum contribution amount in 2019 if under age 50) or self-employed taxpayer plans (solo 401(k)s or SEPs have a $56,000 maximum for 2019).

- Increasing health savings account contributions if the taxpayer is covered by a qualified high-deductible health insurance policy (the maximum employee contribution amount is $3,500 minus employer contributions for an employee with self-only coverage, and $7,000 minus employer contributions if health coverage is for more than self-only in 2019).

- Offset capital gains with capital losses or recognize a net capital loss for the year of up to $3,000 (the maximum net capital loss that can be deducted in the current year).

The opportunity to reduce TIpre-QBIded also exists by increasing itemized deductions above the standard deduction, because a taxpayer deducts the greater of these two amounts. For 2019, the standard deduction is $24,400 for MFJ taxpayers, $18,350 for a taxpayer with the head of household filing status, and $12,200 for an unmarried taxpayer filing single. Generally, the best way to enact this strategy is by accelerating charitable contributions—whether it is donations of cash or appreciated securities.

If an individual taxpayer is going to itemize deductions before considering charitable contributions for the year, then effectively, the entire amount of such contributions will reduce TIpre-QBIded. On the other hand, if the taxpayer is not going to itemize deductions even after such contributions but is close to itemizing, a wise strategy would be to bunch charitable contributions via a multiyear amount contributed in the current year to a donor-advised fund if it leads to itemized deductions substantially exceeding the standard deduction. The donor-advised fund can be set up to give money to charity and spread it across many years, but the entire contribution to the fund is deductible in the year it is made.

Strategies for businesses. Tax planning opportunities also occur at the business entity level. Again, if it appears that the QBI deduction for an SSTB owner is going to be either eliminated or reduced for the current year, the owner will want to consider accelerating business losses and deductions and/or deferring business gains and income. Arguably, implementing business entity level tax-planning strategies is easier for a sole proprietorship or an S corporation; the latter typically has either one or a very small number of often related shareholders. In contrast, the larger the number of owners of a business taxed as a partnership, the more dispersed the owners’ taxable income amounts are, and the more difficult it might be to implement a tax-planning strategy that will satisfy all the owners.

One way to accelerate business deductions, for example, would be to either use first-year bonus depreciation or, if eligible, §179 immediate depreciation expensing, on purchases of tangible personal property; both can lower ordinary income or net profit at the entity level and, potentially, lead to a larger QBI deduction to the owner(s). Greater precision in accelerating depreciation deductions can occur via the latter strategy, since §179 can be taken on an asset-by-asset basis, whereas first-year bonus depreciation is automatic unless the business elects out of it, which can only be done on a class-by-class basis. For example, if the entity does not want first-year bonus depreciation on a piece of seven-year class property (e.g., office furniture) in 2019, it must “elect out” by taking much smaller first-year Modified Accelerated Cost Recovery System (MACRS) depreciation deductions for all seven-year property placed in service in 2019.

Lastly, another opportunity for additional business deductions is retirement account contributions by the entity. A cash balance, qualified, defined benefit plan, for example, can allow as much as $300,000 to an owner-employee’s account depending on his or her age (Burmeister and Stines 2018).

Conclusion

In summary, with careful tax planning at the business entity level, or at least at the individual owner level, some taxpayers who are owners of SSTBs can reduce tax significantly through limiting or eliminating the phase-out of (i.e., increasing) the QBI deduction. This includes financial planning businesses that are not C corporations, as the owner(s) can be subject to this special deduction’s phase-out. It is quite likely that a financial planning business has professional service business clients that are also subject to this phase-out for which tax planning opportunities exist.

The tax-planning considerations mentioned in this article provide a foundation for considering how to maximize the amount of the QBI deduction if phase-out of it is an issue for an SSTB. These tax strategies should be considered in the broader context of the overall financial planning considerations at both the individual and business entity level.

Endnotes

- For 2018, the limit was $315,000 for MFJ and $157,500 for single and head-of-household filing statuses. The threshold is indexed for inflation every year, but the deduction phase-out range for SSTBs—$100,000 for MFJ, and $50,000 for single and head-of-household filing statuses—is the same every year.

- A final category is business based on reputation or skill, but in proposed regulations the Treasury Department states that this is only for business owners earning endorsement fees, appearance fees, and licensing fees (Rosenthal 2018).

- Kitces (2018) wrote about an EffFedMTR as high as 64 percent for MFJ taxpayers for 2018. This analysis assumed QBI was constant at $321,400, whereas Kitces (2018) increased QBI above that amount as TIpreQBIded increases above that amount. When both amounts are larger than $321,400, the QBI deduction before considering the phase-out is greater than $64,280, so the amount phased out as TIpreQBIded increases is also larger, and thus EffFedMTR is also higher.

References

Burmeister, Mike, and Mary Stines. 2018. “5 Key Benefits of Cash Balance Plans.” The Tax Adviser. Available at www.thetaxadviser.com/issues/2018/sep/5-key-benefits-cash-balance-plans.html.

Gardner, Randy, and Leslie Daff. 2018. “2018 Tax Planning Opportunities Under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act.” Journal of Financial Planning 31 (2): 32–34.

Kitces, Michael. 2018. “QBI Deduction Strategies for High-Income Financial Advisors (And Other Small Business Owners).” Nerd’s Eye View. Available at www.kitces.com/blog/high-income-threshold-qbi-deduction-strategies-financial-advisor-specified-service-business.

Rosenthal, Steven M. 2018. “Treasury’s New Pass-Through Rules Double Down on the Deductions Regressivity.” Tax Policy Center. Available at www.taxpolicycenter.org/taxvox/treasurys-new-pass-through-rules-double-down-deductions-regressivity.

Welch, Julie, and Randy Gardner. 2018. “Tax Reform Changes Affect Planners and their Business Clients.” Journal of Financial Planning 31 (3): 42–44.

Citation

Geisler, Greg, and Dawn Drnevich. 2019. “Tax Planning for the Phase-Out of the QBI Deduction for Professional Service Businesses.” Journal of Financial Planning 32 (6): 50–56.