Journal of Financial Planning: July 2018

Amy Hubble, CFA, CFP®, is a doctoral candidate in the department of financial planning at the University of Georgia and is the founding principal at Radix Financial, a fee-only RIA headquartered in Oklahoma City, OK.

Executive Summary

- This research explored the traditional role of gold as an inflation hedge under the economic backdrop of low interest rates and low inflation, specifically during the era of 2008 to 2017, referred to here as the “Great Suppression.”

- During the period studies, gold provided a favorable risk-adjusted return profile to portfolios made up mostly of stocks during a period of low inflation and low interest rates, but offered no yield or guarantee of growth going forward.

- Gold did not offer a favorable risk-adjusted return profile to portfolios made up of mostly bonds, nor to yield-reliant investors.

- Financial planning practitioners can use the results of this study in identifying possible diversification strategies in otherwise aggressive, highly correlated asset portfolios; and as a discouragement to risk-averse, fixed-income-reliant clients.

Much has been written concerning the actions of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors (the Fed) leading up to the global financial crisis, but little has yet to be published concerning the lingering effects of the Fed’s action, or inaction, on consumer household investment in the decade following.

Former Fed Chair Ben Bernanke, in his historical account of Fed action over the previous 100 years (Bernanke 2013a), broke down his analysis in terms of time periods often described as “great,” namely the “Great Experiment” (the Fed’s founding in 1913), the “Great Depression,” the “Great Inflation,” the “Great Moderation,” and the “Great Recession” of 2008–2009. This paper focused specifically on events that occurred during the decade following the Great Recession, between 2008 and 2017, during which the federal funds rate target was held at or near zero percent. That period is referred to here as the “Great Suppression.”1

Gold has long been perceived as a safety trade in times of rising inflation and interest rates (Beckmann and Czudaj 2013; Worthington and Pahlavani 2007). However, the decade from 2007 to 2016 saw the opposite, primarily because of actions taken by the Fed’s Federal Open Market Committee in the wake of the Great Recession. This paper explored whether adding gold to a diversified portfolio of stocks and bonds adds protection through a reduction in standard deviation and an addition of portfolio return.

Using data obtained through publicly available return information from iShares by BlackRock exchange-traded funds (ETFs) and the Federal Reserve of St. Louis database (FRED), this study presents evidence that during the 2008 to 2017 period, gold offered no diversification benefits to conservative portfolio allocations, only to higher equity-weighted portfolios. Equipped with the results of this study, financial planning practitioners can better approach conversations with clients who may have preconceived biases toward investing in this asset class; particularly those who are highly risk-averse or cash-flow reliant.

The Great Suppression

The Federal Reserve System of the United States, originally established in 1913 by President Woodrow Wilson, was designed to “provide the nation with a safer, more flexible, and more stable monetary and financial system.”2 The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) is a committee of the Federal Reserve Board that is charged with conducting the nation’s monetary policy and holds eight scheduled two-day meetings per year, after which a public statement is issued announcing policy changes, if any.

Fed policy is determined in accordance with its dual mandate to pursue: (1) full employment; and (2) stable prices. The Fed is also charged with the supervision of banks and other financial institutions in an effort to “maintain the stability of the financial system and contain systemic risk that may arise in financial markets.”3 It accomplishes this through manipulation of the money supply and credit conditions, as well as serving as the lender of last resort in times of crisis.

The historical effectiveness of various Fed tools and policy decisions have been studied (Bech, Gambacorta, and Kharroubi 2014; Selgin, Lastrapes, and White 2012; Wu and Xia 2016), but such discussions are primarily beyond the scope of this paper. Instead, this paper focused only on the implications of the Fed’s zero-interest rate fed funds target and large-scale asset purchase programs (quantitative easing) on interest rates commonly faced by businesses and consumer households, as well as on inflation and portfolio allocation decisions.

In early fall 2007, the Fed began taking steps to lower the fed funds rate from its 5.25 percent target level, at the time.4 By December 2008, in the three months following the collapse of Lehman Brothers, the target fed funds rate had been dropped to 0.00 percent.5 After the initial panic, the Fed began to pivot its focus away from rescuing faltering institutions to providing monetary accommodation designed to spur economic demand.

Although the recession officially ended in June 2009, GDP growth in the U.S. continued to be slow and the unemployment rate high. In late 2012, the Fed began communicating explicitly under what employment (6.5 percent) and inflation (2 percent) levels would warrant keeping interest rates exceptionally low.6 This created additional downward pressure on long-term rates by reassuring market participants that rates would continue to remain exceptionally low for a considerable time, even after these explicit economic conditions were met.

Both equity and fixed income markets have remained sensitive to Fed policy news, with even slight unexpected changes leading to volatility (Bomfim 2003; Rosa 2011; Zebedee, Bentzen, Hansen, and Lunde 2008). For this reason, the words and verbiage used in meeting minutes, statements, press conferences, speeches, or congressional testimonies made by the Fed chairman and governors were, and continue to be, scrutinized closely.

Brief History of Gold

Gold has had many uses throughout history including as a means of currency exchange. The U.S. has only relatively recently (within about the last 50 years) switched from the gold standard to a full fiat monetary system, going as far as outlawing the private ownership of gold coin, bullion, or currency between 1933 and 1974. The future of gold as an investment is unclear, and disagreement amongst investors and researchers persist. Erb and Harvey (2013) postulated six common arguments for owning gold: (1) inflation hedge; (2) currency hedge; (3) alternative to assets with low real returns; (4) safe haven in times of stress; (5) return to de facto gold standard; and (6) portfolio under-ownership in terms of global market cap.7 The authors concluded that these six arguments were related to the common theme of inflation protection.

Empirical evidence has shown that gold has, at times, provided a portfolio hedge against inflation as well as a safe haven in market downturns (Batten, Ciner, and Lucey 2014; Baur and Lucey 2010; Ghosh, Levin, Macmillan, and Wright 2004). However, studies have also shown that the relationship is time-varying (Beckmann and Czudaj 2013; Batten, Ciner, and Lucey 2014), and may not consistently provide a portfolio inflation hedge.

Today, gold is frequently purchased for investment purposes. Investors can choose among various exposure vehicles, including within a mutual fund or ETF (that may invest in gold directly or through futures contracts), gold mining stocks, or directly by purchasing physical gold bars, coins, or jewelry. Consider that there are three types of assets:

Use assets, which are bought primarily to use, consume, or enjoy such as cash, a car, boat, or an engagement ring. They hold value and can be resold, but profit is not the primary objective for ownership.

Investment assets, which are purchased and expected to grow in value over time, provide consistent income over time, or both. Examples are long-term retirement account assets, buy-and-hold equity investments, oil and gas royalty interests, closely held businesses, rental houses, etc.

Trading assets, which are generally purchased for risk-management purposes or because of a belief that there is an opportunity within the current or future market for resale at a higher price, therefore gaining profit. Generally shorter-term in nature, trading assets may or may not provide any cash flow during the holding period such as precious metals, foreign currency contracts, derivative contracts, and equity day trading. Sometimes these are also referred to as speculative investments.

These categories are not mutually exclusive. A home, for example, can be both a use asset and an investment asset. Stocks and ETFs can be purchased and held as investment assets for decades growing steadily and distributing dividends to the owner, or they can be aggressively traded back and forth throughout the day as trading assets. Gold exposure most closely resembles the characteristics of a trading asset, but in some cases could be considered a hybrid.

Physical gold can be made into jewelry or collectibles as a use asset, or held in vaults as a diversifying investment asset. In this case, and in all cases, a buyer and seller must accept that there is value and agree on a means and denomination of exchange for that value (traditionally government currency—such as the U.S. dollar), before a value-for-value exchange can be made.

Erb and Harvey (2013) compared these characteristics to the Keynesian “beauty contest” idea that the price of gold is not necessarily determined by what the investors themselves believe gold to be worth, but instead on their estimation of what others believe gold to be worth.

Data

This study covered the period between January 2008 and December 2017, referred to here as the Great Suppression. It compared portfolios with and without gold exposure to determine whether they differed significantly on a risk-adjusted basis over the specified period. The data included returns from an ETF that holds gold bullion within its trust structure, rather than the return of an ounce of gold owned outright. Because of the complications and expense of acquiring, transporting, storing, and insuring physical gold are very high, it is more efficient for individual investors to gain exposure through a mutual fund or ETF.

All ETF return data was supplied by publicly downloadable information on the iShares by BlackRock website, ishares.com, and represents the month-end total net asset value (NAV) return for each vehicle. The three ETFs used in this study were: (1) iShares S&P 500 Index ETF (IVV), which tracks the S&P 500 U.S. large-cap equity index; (2) iShares Core U.S. Aggregate Bond ETF (AGG), which tracks the Barclays U.S. investment-grade bond index; and (3) iShares Gold Trust ETF (IAU), which holds gold bullion directly.

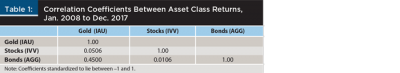

Table 1 examines the correlations between each asset class. Most finance textbooks, financial planning software, and professional financial certification bodies, such as CFP Board and CFA Institute, advocate that portfolios be selected using a mean-variance optimization (MVO) framework. Harry Markowitz’s Nobel Prize-winning modern portfolio theory (Markowitz 1952) proposed that investors maximize returns by combining low-correlated assets along the efficient frontier for a given level of risk through mean-variance optimization. The benefits of diversification are therefore illustrated by the combined risk (as measured by standard deviation) of a portfolio of assets being less than the weighted-average risk of the individual assets. Low correlations between stocks (IVV), bonds (AGG), and gold (IAU) indicate that adding gold to a portfolio made up of stocks and bonds will likely result in diversification benefits.

Methodology

The primary question this study sought to answer was whether the inclusion of gold to portfolios made up of stocks and bonds increased portfolio risk-adjusted diversification benefits, as defined by the Sharpe ratio. For this, portfolio risk/return characteristics were compared, when gold was added in different magnitudes, to ascertain whether there was any risk-adjusted return benefit over the period.

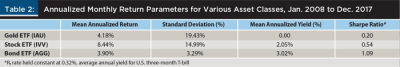

Table 2 illustrates mean annualized returns for the individual asset classes. Stocks had the highest mean annualized return, while bonds had the lowest standard deviation. All else equal, a higher Sharpe ratio indicates higher risk-adjusted return, where Rp is the return on the portfolio, Rf is the riskless rate investors can borrow or lend at, and σp is the standard deviation of the portfolio:

The measure of mean annualized return represents the 10 years of month-end total returns, geometrically averaged and annualized to produce an average per year percentage return. Mean annualized yield is the average annualized percentage of market value paid out in cash distributions, in the form of dividends or interest, paid back to the investor. This yield figure is included in the total return calculation, and therefore should not be considered in isolation; however, it is broken out here for illustration, due to its importance to many financial planning strategies and assumptions.

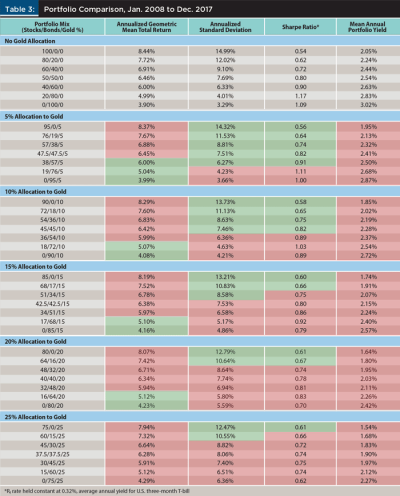

The results from back-tested portfolio return data are presented in Table 3. Seven hypothetical ETF portfolio mixes, from very aggressive (100 percent stocks) to very conservative (100 percent bonds) are presented for comparison. The same stock-to-bond proportions were maintained across all portfolios, the only differentiator being the proportionate gold weighting.

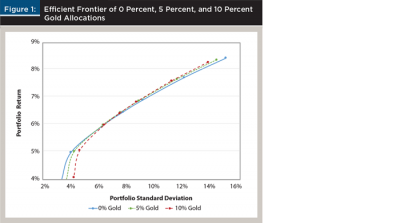

Green color coding illustrates improvement over the previous base case portfolio; whereas diminished benefits are coded red. When 5 percent of gold was proportionately added to the portfolio, return was improved in bond-heavy portfolios, at the cost of additional standard deviation and diminished portfolio diversification. This decreased Sharpe ratio can be interpreted as an unnecessary assumption risk for each incremental increase in return, and falling below the efficient frontier as illustrated in Figure 1.

When 10 percent of gold was added to the portfolio, the same relationship was found. Gold improved portfolio efficiency when added to diversified portfolios of mostly stocks, but was diminished for portfolios made up of mostly bonds. Portfolio yield was diminished with any addition of gold, because gold has no cash yield and would be inappropriate for inclusion in distribution-dependent portfolios.

Limitations

Although gold exposure did offer risk-adjusted diversification benefits for many of the portfolios evaluated, this study in no way attempted to assert that the observed results will persist in the future. Past performance is not indicative of future returns. Gold and other trading assets should be evaluated within a mean-variance optimized efficient portfolio framework, with professional judgement applied to the goals and constraints of a potential investor. Gold has little intrinsic value and offers no cash yield or dividend payment, making cash flow valuation and accurate future return forecasting unfeasible. Gold should instead be considered as a portfolio risk reducer, due to its low correlations with other asset classes, rather than an absolute return enhancer.

In addition, the utilization of a mean-variance optimized portfolio framework must make several assumptions, often not considered operationally feasible in the practice of financial planning. These assumptions include: (1) investors are rational; (2) markets are free and impose no tax or transaction costs; and (3) all investors have access to the same information, including expected returns, variances, and covariances for all assets.

This study assumed that each portfolio was rebalanced monthly to the target weighting, and that each trial allocation was held the entire 10-year period. In reality, such frequent rebalancing would incur transaction costs, management fees, and taxes, which would diminish net return. The benefit of hindsight also allowed for accurate efficient portfolio selection within the study, whereas expected future returns must usually be forecasted by financial planners in establishing mean-variant efficient portfolio models.

Financial Planning Implications

This study attempted to illustrate the means and purpose for investing in gold during a low-interest rate, low-inflation environment such as the Great Suppression era of 2008 to 2017. This period of low interest rates was great for borrowers, corporate lending, and equity investors. However, for risk-averse investors, defined benefit pension plan sponsors, private foundations subject to minimum distributions, and those who depend on investment income to meet monthly expenses, it was difficult to earn a positive net real rate of return.

For investors willing to accept more volatility in portfolio returns, they were rewarded. Even including the recessionary period of 2008 to 2009, investors in the S&P 500 index would have earned an average annualized 8.44 percent for the last 10-year period ending Dec. 31, 2017.

With dividends yields (which enjoy favorable tax treatment) higher than the 10-year U.S. Treasury note for most of the period, even risk-averse yield-seekers would have been better off with higher equity allocations. Although equity portfolio shares are generally higher for investors with longer time horizons (Spaenjers and Spira 2015), fewer than 15 percent of American households report owning stocks directly, and only about 50 percent have exposure through mutual funds or retirement accounts (Bricker et al. 2017). Given this, Great Suppression-era retirees could now be woefully underprepared for retirement (Pfau 2011; West 2010).

For this reason, uncovering the optimal level of risk for portfolio allocation recommendations is key for successful financial planning. Figure 1 illustrates the efficient frontier of three portfolio sets: 0 percent, 5 percent, and 10 percent gold allocations. A client’s relative risk aversion applied to mean-variance optimization analysis gives a financial planner the tools to choose amongst appropriate portfolio allocation choices along the efficient frontier. Only portfolio allocations lying on the efficient frontier would be chosen, with portfolios lying above the curve (more return for the same amount of risk), deemed impossible to obtain within an efficient market, and portfolios lying below to curve (less return for the same amount of risk), inefficient. Here, both the 5 percent and 10 percent gold allocation portfolios were below the efficient frontier for portfolio choices offering lower standard deviation, meaning there is a portfolio that offers a higher return for the same level of risk, illustrated by the 0 percent gold portfolio line that should be chosen in such a scenario.

Inversely, allocations to gold within more aggressive portfolios offer higher portfolio efficiency; indicating a more favorable risk-adjusted return trade-off. For financial planners with clients who believe gold to be an appropriate “safety trade,” the results of this study can be used to illustrate that diversification benefits have historically been applied only to high equity-weighted portfolios, often at the expense of lower return and portfolio yield. This analysis establishes historical precedence for recommending small allocations to gold to reduce risk in otherwise high standard deviation portfolios under the economic backdrop of low-interest rates and inflation.

Conclusion

The exact timing and means by which the Fed will continue to tighten will continue to depend on economic conditions. The Fed has issued and communicated plans to move the target rate higher by slowly increasing the fed funds target rate, increasing the interest rate on excess reserves, and to a lesser extent, offering overnight reverse repurchase agreements (Ihrig, Meade, and Weinbach 2015). Beginning at its December 2015 meeting, the FOMC began the normalization process by modestly raising its target federal funds rate range by 0.25 percent,8 and it is widely expected that additional increases will continue.9

History will ultimately judge the actions of the Fed during the Great Suppression era, but many unknowns still exist for investors going forward. Bernanke (2013b) perhaps put it best when he remarked that “the first risk is that rates will remain low, and the second is that they will not.”

As fixed income rates rise, the opportunity cost of owning gold or other nonproductive assets grows higher. If rates persist near zero, investors will be forced to add additional risk to their portfolios to generate yield. As this study illustrated, gold may provide a favorable risk-adjusted return profile to traditional portfolios comprised mostly of stocks during periods of low inflation and low interest rates, but offers no yield or guarantee of growth going forward. For risk-averse retirement savers, the risks of not reaching their retirement goals, coupled with losing money in “safe” investments have large consequences, and they should not include gold in core portfolios.

Endnotes

- The “Great Suppression” reference used here should be not confused with the 2016 book by Zachary Roth of the same name.

- See “About the Fed” (last modified April 22, 2016) at federalreserve.gov/faqs/about-the-fed.htm.

- See “What Is the Purpose of the Federal Reserve System?” at federalreserve.gov/faqs/about_12594.htm.

- See the Sept. 17, 2007 FOMC statement at federalreserve.gov/newsevents/pressreleases/monetary20070918a.htm.

- See the Dec. 16, 2008 FOMC statement at federalreserve.gov/newsevents/press/monetary/20081216b.htm

- .

- See the Dec. 12, 2012 FOMC statement at federalreserve.gov/newsevents/pressreleases/monetary20121212a.htm.

- Many of these same arguments have been postulated for cryptocurrencies, specifically Bitcoin, which is described often as “digital gold.” See Anne H. Dyhrberg’s 2016 article, “Hedging Capabilities of Bitcoin. Is It the Virtual Gold?” in Finance Research Letters.

- See the Dec 16, 2015 FOMC statement at federalreserve.gov/newsevents/pressreleases/monetary20151216a.htm.

- See the June 4, 2018 Bloomberg article “The Fed Will Soon Switch Off the Autopilot” available at bloomberg.com/view/articles/2018-06-04/the-fed-s-key-interest-rate-is-getting-close-to-neutral.

References

Batten, Jonathan A., Cetin Ciner, and Brian M. Lucey. 2014. “On the Economic Determinants of the Gold–Inflation Relation.” Resources Policy 41 (1): 101–108.

Baur, Dirk G., and Brian M. Lucey. 2010. “Is Gold a Hedge or a Safe Haven? An Analysis of Stocks, Bonds and Gold.” The Financial Review 45 (2): 217–229.

Bech, Morten L., Leonardo Gambacorta, and Enisse Kharroubi. 2014. “Monetary Policy in a Downturn: Are Financial Crises Special?” International Finance 17 (1): 99–119.

Beckmann, Joscha, and Robert Czudaj. 2013. “Gold as an Inflation Hedge in a Time-Varying Coefficient Framework.” The North American Journal of Economics and Finance 24: 208–222.

Bernanke, Ben S. 2013a. “A Century of U.S. Central Banking: Goals, Frameworks, Accountability.” The Journal of Economic Perspectives 27 (4): 3–16.

Bernanke, Ben S. 2013b. “Long-Term Interest Rates.” Presentation at the Annual Monetary/Macroeconomics Conference: The Past and Future of Monetary Policy, San Francisco, CA, March 1, 2013.

Bomfim, Antulio N. 2003. “Pre-Announcement Effects, News Effects, and Volatility: Monetary Policy and the Stock Market.” Journal of Banking & Finance 27 (1): 1

33–151.

Bricker, Jesse, Lisa J. Dettling, Alice Henriques, Joanne W. Hsu, Lindsay Jacobs, Kevin B. Moore, Sarah Pack, John Sabelhaus, Jeffrey Thompson, and Richard A. Windle. 2017. “Changes in U.S. Family Finances from 2013 to 2016: Evidence from the Survey of Consumer Finances.” Federal Reserve Bulletin 103, available at federalreserve.gov/publications/2017-September-changes-in-us-family-finances-from-2013-to-2016.htm.

Erb, Claude B., and Campbell R. Harvey. 2013. “The Golden Dilemma.” Financial Analysts Journal 69 (4): 10–42.

Ghosh, Dipak, Eric J. Levin, Peter Macmillan, and Robert E. Wright. 2004. “Gold as an Inflation Hedge?” Studies in Economics and Finance 22 (1): 1–25.

Ihrig, Jane E., Ellen E. Meade, and Gretchen C. Weinbach. 2015. “Rewriting Monetary Policy 101: What’s the Fed’s Preferred Post-Crisis Approach to Raising Interest Rates?” The Journal of Economic Perspectives 29 (4): 177–198.

Markowitz, Harry. 1952. “Portfolio Selection.” The Journal of Finance 7 (1): 77–91.

Pfau, Wade D. 2011. “Will 2000-Era Retirees Experience the Worst Retirement Outcomes in U.S. History? A Progress Report After 10 Years.” The Journal of Investing 20 (4): 117–131.

Rosa, Carlo. 2011. “Words that Shake Traders: The Stock Market’s Reaction to Central Bank Communication in Real Time.” Journal of Empirical Finance 18 (5): 915–934.

Selgin, George, William D. Lastrapes, and Lawrence H. White. 2012. “Has the Fed Been a Failure?” Journal of Macroeconomics 34 (3): 569–596.

Spaenjers, Christophe, and Sven Michael Spira. 2015. “Subjective Life Horizon and Portfolio Choice.” Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 116: 94–106.

West, John. 2010. “Hope Is Not a Strategy.” Research Affiliates’ Fundamental Index Newsletter, available at researchaffiliates.com/documents/F_2010_Oct_Hope_is_Not_Strategy.pdf.

Worthington, Andrew C., and Mosayeb Pahlavani. 2007. “Gold Investment as an Inflationary Hedge: Cointegration Evidence with Allowance for Endogenous Structural Breaks.” Applied Financial Economics Letters 3 (4): 259–262.

Wu, Jing Cynthia, and Fan Dora Xia. 2016. “Measuring the Macroeconomic Impact of Monetary Policy at the Zero Lower Bound.” Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 48 (2–3): 253–291.

Zebedee, Allan A., Eric Bentzen, Peter R. Hansen, and Asger Lunde. 2008. “The Greenspan Years: An Analysis of the Magnitude and Speed of the Equity Market Response to FOMC Announcements.” Financial Markets and Portfolio Management 22 (1): 3–20.

Citation

Hubble, Amy. 2018. “The Great Suppression: Actions and Implications for Gold Investors.” Journal of Financial Planning 31 (7) 46–52.