Journal of Financial Planning: January 2015

Robert Albright, Ph.D., is a professor at the University of New Haven. His research has been published in a variety of journals, including Industrial and Labor Relations Review and the Journal of Labor Research. He consults with various organizations including General Dynamics, Pfizer, United Technologies Corp., ING, and Symmetry Partners LLC.

John B. McDermott, Ph.D., is an associate professor of finance at Fairfield University. His research has been published in various finance journals, including the Journal of Banking and Finance and the Journal of Financial Markets. He is the chief investment strategist at Symmetry Partners LLC.

Acknowledgements: The authors thank two anonymous referees and the editor for their thoughtful comments and suggestions. We also thank David Connelly, Pat Sweeny, Dana D’Auria, Jason Gentile, and the participants in the 2013 Symmetry Advisory Committee meeting in Miami, Florida.

Executive Summary

- This research explores the proposal that the Zimbardo Time Perspective framework can be a powerful tool applied in the practice of financial planning.

- Use of the associated assessment instrument, the Zimbardo Time Perspective Inventory, can provide financial planners increased self-awareness of their own time perspective, and it may provide a framework that helps explain the preferences, attitudes, and behavioral tendencies of their clients.

- Results drawn from the administration of the inventory to a convenience sample of independent financial planners was used to posit that planners are likely to differ from the general population in regard to their orientation toward time.

- Support was found for the notion that it behooves financial planners to become aware of their own time perspective and how it may differ from that of their clients

Philip Zimbardo and John Boyd (1999) developed a paradigm through which to better understand human behavior. They argued that people are all subject to unique predilections with respect to time. Some individuals tend to focus more on past events, while others are firmly rooted in the present, and still others tend to focus on the future.

Key insights regarding how individuals make decisions can be derived from understanding an individual’s dominant time perspective (TP) orientation. Zimbardo and others contend that TP inclinations can have profound impacts on attitudes and conduct in a wide range of areas as diverse as the tendency to engage in risky behavior to susceptibility to afflictions such as post-traumatic stress disorder.

In this paper, we consider the potential use of Zimbardo’s TP construct in the practice of financial planning. Specifically, this study contends that financial planners should know their own individual orientation toward time, and that they should (in conjunction with their client) explore their clients’ time orientation. Such insight is valuable, because it may increase a financial planner’s awareness of how TP influences the financial advice they tend to provide, allow for increased understanding of individual clients’ behavioral investment and consumption tendencies, and serve as a basis of conversation between planners and clients regarding investing biases.

The aim of this paper is to provide financial planners another tool by which to better understand themselves and their clients, both present and prospective. Findings are based on a pilot study using a small convenience sample of financial planners in order to explore whether planners differ from the general population in terms of their TP profile. It was hypothesized that financial planners would tend to be more future orientated.

The TP Construct and Financial Planning

In presentations where Zimbardo explains the TP concept (for example, see Zimbardo’s 2009 TED Talk, “The Psychology of Time”), he often describes the famous marshmallow experiment originally conducted at Stanford University by Mischel, Ebbeson, and Zeiss (1972). In this experiment, children were given the choice of eating a marshmallow immediately or waiting five minutes in order to receive two marshmallows. Mischel, Shoda, and Rodriquez (1989) followed the young children into their adulthood and found that the subjects who were able to resist the temptation to consume the marshmallow immediately fared better in life, measured on myriad intellectual and psychological dimensions, compared to the subjects who could not resist the immediate gratification. The original marshmallow experiment and its subsequent studies have often been used to characterize the importance of impulse control and delayed gratification.

One can immediately see the similarities between the scenario presented to these young children and the investment-consumption decisions integral to the practice of financial planning.

The canonical portfolio choice problem explored in the finance literature1 posits that rational utility-maximizing investors allocate their income between consumption today and investing in a portfolio of risky assets in order to provide for consumption in the future. The investor’s investment-saving and portfolio choices are made to maximize the lifetime utility of consumption. The specific trade-off implicit in the solution to the portfolio problem is that the investor will consume so that the additional utility of the consumption today is exactly equal to the additional expected utility of the future consumption. In a simple, two-period model, the investment-consumption decision becomes a function of the trade-off experienced by the individual investor between consuming today and postponing consumption until the next period. This is known as the time-preference for consumption. Thus, as in the marshmallow experiment, the investor’s time perspective is important. Interestingly, investors may not be that different from young children deciding whether to eat a marshmallow immediately or to wait.

Further, it is now well established (Kahneman and Tversky 1981; Shefrin 2002) that individuals have psychological biases that challenge the assumption of the rational investor. As a result, financial planners are well advised to become versed in human behavior in general, and what may be driving their clients’ investment and consumption decisions in particular.

Festinger’s (1957) work identified beliefs and attitudes as important antecedents to behavior. Zimbardo and Boyd (1999) expanded on the importance of attitudes, specifically toward time, in understanding human behavior. They stated, “…TP is a fundamental psychological dimension from which more complex psychological constructs may emerge and to which more complex psychological constructs may be related” (p. 1,280). They contended that individual tendencies to habitually emphasize a particular time frame may exert a dynamic influence on important decisions. For example, individuals with a past orientation may focus on analogous past experiences when making decisions. They may consider positive past experiences or negative past experiences, and these considerations may affect their current decision-making behavior. Those with a tendency to emphasize a future time frame may extend the present scenario and consider the costs and benefits associated with today’s decisions on some future time period. Lastly, those with a present-oriented tendency may be overly influenced by aspects of the current environment that will provide biological, sensory, or social outcomes.

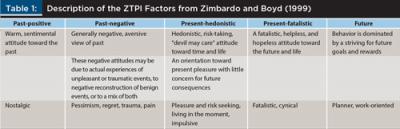

Zimbardo and Boyd (1999) further refined the past, present, and future time frames into five dominant time perspectives that can be measured with a psychological survey, the Zimbardo Time Perspective Inventory (ZTPI). Table 1 provides a summary of each of the five TPs from Zimbardo and Boyd. Briefly, the five time perspectives2 measured by the ZTPI are:

- Past-positive: a time perspective that focuses on positive or nostalgic past events

- Past-negative: a time perspective that focuses on negative past events

- Present-hedonistic: a time perspective focused on the positive sensory, biologic, or social outcomes associated with the present environmental context

- Present-fatalistic: a perspective marked by a hopeless, helpless attitude toward the future

- Future: a perspective marked by a general future orientation (the future scale developed for the ZTPI suggests that behavior is dominated by a quest for future rewards)

Academic research has shown that TP is a powerful psychological construct and that the ZTPI is a useful tool that can be used to understand a wide range of human behaviors. For example, the present time perspective, as measured by a modified and shortened ZTPI instrument, was found to be related to reports of risky driving (Zimbardo, Keough, and Boyd 1997) and also to more frequent smoking, consumption of alcohol, and drug use (Keough, Zimbardo, and Boyd 1999). D’Alessio, Guarino, DePascalis, and Zimbardo (2003) also used the short-form ZTPI and TP to understand cultural differences. Other applications of the time perspective construct include making appeals to suicidal terrorists, reducing burnout, combatting addictions, preventing school dropouts, and treating post-traumatic stress disorder. Clearly, given the role of time in the classical view of investing, the TP construct may provide a deeper meaning and more insight than is conveyed in finance theory by the time perspective for consumption parameter in an investor’s utility maximization problem.

Given the future-oriented nature of their work, we hypothesized that financial planners would score higher on the future measure of the ZTPI than the general population. The rational cost-benefit analysis and future orientation associated with financial planning may draw future-oriented candidates into the profession. It is also possible financial planners need to constantly focus on the future when counseling clients, which impacts their dominant TP. In this paper, we analyzed the TP of a convenience sample of financial planners to test this possibility.

Time Perspective, Client Behaviors, and Investor Biases

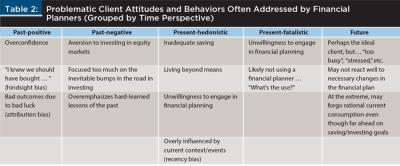

We grouped problematic client attitudes and behaviors by the five TPs based on the assumption that planners are well versed in the tenets of investments and financial planning best practices, and that one of their primary roles is to counsel their clients’ away from counter-productive behaviors. These groups are presented in Table 2. The list refers to problematic client investment attitudes and behaviors rather than those of financial planners.

Past-oriented. The ups and downs of investing in the markets can test the resolve of even the most rational and committed investor. Past-oriented individuals will have significant experiences both in bull (2003–2007) and bear (2008–2009) market environments upon which to dwell. The key is to maintain a healthy balance between the reflection on positive and negative experiences. Planners sometimes are challenged by clients who were so emotionally scarred by the drawdowns in 2008–2009 that it prevents them from returning to investing in the stock market.

Many psychological biases related to investing can be seen through the lens of time perspective. As in Nofsinger (2013), well-known psychological biases such as attribution bias and hindsight bias can be understood as distortions of the past. With attribution bias, successes are viewed to have occurred because of the positive attributes of the investor, such as intelligence, skill, or a keen intuition but not necessarily good luck. Alternatively, investment failures are viewed to have occurred as a result of factors outside of the investor’s control, such as world-wide financial crises or just simply bad luck. Hindsight bias allows an investor to look back and say, “I knew that this was going to be a great year to invest in … .” Attribution and hindsight biases therefore can be seen as a form of nostalgia, which is simply a way of looking back positively at the past while ignoring or minimizing the negative.

Present-oriented. Present-oriented individuals tend to decide and act in the moment. As such, they may be prone to chasing returns, getting out of the markets in difficult times, rotating to hot sectors, and increasing risk in bull markets. Recency bias, where recent observations are weighted more heavily when making decisions, is consistent with a strong present-orientation. Thus, present-oriented individuals may be the clients asking advisers to invest in penny stocks or highly speculative bets that they recently heard about via peers or the media. Further, present-oriented clients will need to exhibit some delayed gratification in order to save adequately for their financial future. In fact, it may be that these individuals will be the most difficult to bring into a planning practice, as planning for the future may be anathema to them.

Future-oriented. This may be the ideal dominant TP for clients of a financial planner. Future-oriented clients’ rational cost-benefit analyses and orientation toward tomorrow makes financial planning a welcome exercise. It may be that the majority of clients are future-oriented. Excessive future orientation can also be a detriment in that the individual may have an “all work and no play” attitude. However, they may be inflexible and not react well to the inevitable changes necessary in financial plans.

The Ideal Time Perspective

Zimbardo and Boyd (2005) conjectured an ideal time perspective profile for those living in a Western society. They hypothesized the following ideal time perspective in order to promote the notion of a balanced time perspective that would allow someone to learn from the past, adapt to and enjoy the present, and prepare for the future:

“For Western society, or at least for the United States, we believe that this optimal profile of time perspectives includes: moderate levels of future and present-hedonism, blended with high levels of past-positive time perspective… . It should be clear that in such a total package, one would want only the lowest levels of past-negative and present-fatalism.” (p. 101)

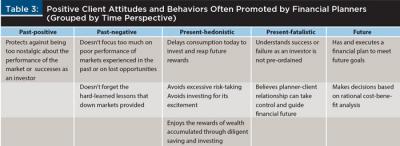

More specifically, Zimbardo and Boyd (2005) reported that a healthy and balanced TP profile would be high in past-positive, moderate in present-hedonistic and future, and low in past-negative and present-fatalistic. We contend the Zimbardo and Boyd ideal TP profile would be generally aligned with the productive investing practices promoted by financial planners. Given this paper’s focus on financial planners and their role in influencing client attitudes and behavior toward productive investing practices, we proposed that a healthy and balanced TP would engender the positive attitudes and behaviors outlined in Table 3.

Specifically, planners have a role in enabling clients to plan for the future, delay gratification, and save, while not being overly tied to the past. Compared to Zimbardo and Boyd’s conceptualization of ideal, we contend that ideal client behavior stems from a high (not moderate) future-orientation and a moderate (not high) orientation toward past-positive. This would likely increase the emphasis on planning for the future, while not falling prey to the investment biases related to a nostalgic versus a realistic view of past investment experiences. Clients with a healthy and balanced TP will have a respect for the past and markets, will enjoy life and its material pleasures within their means, and will engage in planning and make rational cost-benefit decisions in planning for their future.

By the nature of their work, we hypothesized that financial planners would have a healthy respect for the past, both positive and negative. Regarding the present, we did not expect to see fatalism score as a strong orientation, but we had no expectations regarding financial planners’ relative orientation toward hedonism.

Methods

The ZTPI was administered to 25 fee-based financial planners who conduct significant business with Symmetry Partners LLC, a turnkey asset manager in Glastonbury, Connecticut. The planners generally subscribe to a passive, factor-based investment philosophy, and are located across the United States. The sample consists of primarily men (three respondents identified as female) between the ages of 28 and 64. The participants were college graduates, U.S. citizens, and Caucasian. The sample is best characterized as convenient and non-random, and thus the study should be considered preliminary or a pilot.

The ZTPI is a 56 multiple item survey3 where respondents answer the question “How characteristic or true is this of me?” to each item on a five-point scale ranging from “Very Untrue” to” Very True.” For illustration purposes, the first of 56 items on the ZTPI is, “I believe that getting together with one’s friends to party is one of life’s important pleasures.” Somewhat obviously, this item is designed to estimate a respondent’s attitude toward the present-hedonistic TP. The 56 responses were summed into the five TPs and tallied to form a score for each.4

Results

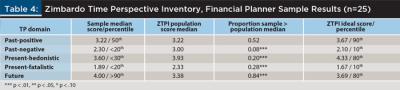

The ZTPI results for the sample are presented in Table 4. The first column reports the financial planner sample median score and its corresponding ZTPI population percentile. The second column reports the median (50th percentile) value for the entire ZTPI population. The third column reports the percentage of financial planner sample scores that were above the ZTPI population median. The fourth column reports Zimbardo’s ideal ZTPI both by score and corresponding population percentile. The Zimbardo population data for median and ideal percentiles were taken from his ZTPI survey website (www.thetimeparadox.com/surveys).

A test for the difference in medians was conducted using a simple sign test that the proportion of financial planner sample scores above the Zimbardo population median was equal to 0.5. In general, the planner sample differed significantly from the Zimbardo population in four of the five TPs. Only in past-positive were the sample medians not statistically different.

In comparison to Zimbardo’s ideal, the planner sample was higher than ideal for future and lower than ideal for past-positive and present-hedonistic. Specifically, on past TPs, the planner sample was near the population median for past-positive but below Zimbardo’s ideal at the 90th percentile.

For past-negative, the planner sample was near the Zimbardo ideal at the 10th percentile. The sample median for past-negative was statistically different from the ZTPI population median (p < .01).

For the present TPs, the sample was well below both the population median and the Zimbardo ideal for present-hedonistic. For present-fatalistic, however, the sample was very near the ideal at the 10th percentile. For both present TPs, the sample medians were statistically different from the ZTPI population medians (p < .01).

As hypothesized, the financial planner sample was very high on future, scoring at above the 90th percentile, which is greater than the population median and Zimbardo’s ideal. The sample median for future was statistically different from the ZTPI population median (p < .01).

The combination of high-future and low-hedonistic was labeled as “all work and no play” by Zimbardo and Boyd (2005), where they cautioned that vocational success may not transfer to healthy social relationships. Of course, this suggests financial planners, on average, may be hard-working and future-oriented to a fault. Individual advisers should self-assess and decide for themselves if they need to “stop and smell the roses.”

Limitations

As stated earlier, this study was preliminary and exploratory by design. This was due primarily to the smaller, non-random nature of the financial planner sample. Thus, we caution readers to be careful not to overgeneralize the findings. We contend the research provides motivation for research projects worthy of future study. For example, larger scale studies of planner and client TP and their characteristics could provide further insight into the success of a financial planner, a client, and their relationship.

Potential Applications and Future Directions

The aim of this paper has been to provide financial planners with another tool by which to better understand themselves using a framework that will enhance their ability to advise present and prospective clients. As illustrated, the TP construct can be applied in the practice of financial planning as a way to enhance planner self-awareness, while providing a rubric that will allow insight into what may be driving their clients’ attitudes and behaviors.

Although this research does indicate that the TP of a financial adviser sample differs from the TP of the general population, the research is preliminary and has limitations.

Further research is needed to parallel research with samples drawn from the clients of financial planners in order to determine whether planners do indeed differ significantly, in terms of TP orientation, from the orientation that is found in a typical client base. Further research and testing is also warranted across different financial planner communities, for it could potentially reveal TP differences across planning professionals who advocate and practice different investment strategies (active versus passive strategies) or compensation schema (fee-based versus commission).

Given the criticality of planner-influenced decisions to the financial health and well-being of their clients, it is imperative that financial planners carefully consider their own TP orientation. Only by being completely self-aware of their own perspectives in regards to time can planners hope to avoid subconsciously over-applying their own orientation to the advice that guides their clients’ financial decision-making. Enhanced cognizance of a planner’s own TP orientation—as it compares to the norms of the population and to his or her client base—may well allow for an increased ability to provide sound advice that aligns with their clients’ financial objectives, even if those objectives differ greatly from those that might have been chosen by the planner.

Financial planners who become knowledgeable and fluent in the language of TP may also eventually become capable of assessing their clients’ time perspectives. Conceivably, planners might clinically assess their client’s TP via a cataloging of client discussions and behavioral tendencies, or via the administration of the ZTPI. Knowledge of a client’s TP could assist planners with their ability to temper clients’ tendencies to fall prey to the common investor biases noted earlier in this paper. It is conceivable that the ZTPI could also be used as a self-assessment tool that may enhance client self-awareness of a construct central to their investment behavior pre-dispositions. The assessment could additionally be leveraged to serve as the basis for an in-depth, relationship-building conversation at the beginning of any planner-client engagement.

A common practice used by executive coaches at the beginning of any coaching engagement is to administer to clients a battery of psychometric instruments designed to assess different aspects of each client’s personality. The resulting assessments not only enhance the client’s self-awareness, they serve as a basis for a relationship-building conversation between the coach and the client. It would be worth exploring whether the ZTPI could be used in an analogous fashion at the beginning of a planner-client relationship.

Given the future-orientation of the financial planning profession, it would not be a surprise to find that clients seeking financial advice would tend to be future-oriented as well. For clients with a strong future-orientation, stressing the importance of saving and investing for future major financial events, such as retirement or college tuition, would be a wise strategy, and probably the strategy most commonly used by financial planners during their prospecting activities.

We suggest that planners consider broadening their TP appeal across the past and present time domains when prospecting clients. By appealing to the positive experiences of the past and the current benefits realized by planning, financial planners may resonate with a wider group of prospective clients.

Endnotes

- See Cochrane (2005) for a comprehensive exposition.

- Zimbardo later added “Future-transcendent” as a sixth TP to accommodate those who are motivated by the considerations of the future after their death and to make distinct from “Future-lifetime.” An extreme example of “Future-transcendent” dominant individuals is the suicide bomber motivated by eternal bliss.

- View the questionnaire at www.thetimeparadox.com/zimbardo-time-perspective-inventory.

- For more in the scoring process, see www.thetimeparadox.com/surveys.

References

Cochrane, John H. 2005. Asset Pricing (revised ed.). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

D’Alessio, Marisa, Angela Guarino, Vilfredo DePascalis, and Philip G. Zimbardo. 2003. “Testing Zimardo’s Time Perspective Inventory—Short Form: An Italian Study.” Time and Society 12 (2): 333–347.

Festinger, Leon. 1957. A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance. Redwood City, CA: Stanford University Press.

Kahneman, Daniel and Amos Tversky. 1981. “The Framing of Decisions and the Psychology of Choice.” Science 211 (4481): 453–58.

Keough, Kelli A., Philip G. Zimbardo, and John N. Boyd. 1999. “Who’s Smoking, Drinking, and Using Drugs? Time Perspective as a Predictor of Substance Use.” Basic and Applied Social Psychology 21 (2): 149–164.

Mischel, Walter, Ebbe B. Ebbeson, and Antonette Zeiss. 1972. “Cognitive and Attentional Mechanisms in Delay of Gratification.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 21 (2): 204–218.

Mischel, Walter, Yuichi Shoda, and Monica L. Rodriguez. 1989. “Delay of Gratification in Children.” Science 244 (4907): 933–938.

Nofsinger, John, R. 2013. The Psychology of Investing (5th ed.). New York: Pearson Series in Finance.

Shefrin, Hersch. 2002. Beyond Greed and Fear: Understanding Behavioral Finance and the Psychology of Investing (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Zimbardo, Philip, G. and John Boyd. 1999. “Putting Time in Perspective: A Valid, Reliable Individual-Differences Metric.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 77 (6): 1271–1288.

Zimbardo, Philip G., and John N. Boyd. 2005. “Time Perspective, Health, and Risk Taking,” in Understanding Behavior in the Context of Time: Theory, Research, and Application edited by Alan Strathman and Jeff Joireman. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Zimbardo, Philip G. and John N. Boyd. 2009. The Time Paradox: The New Psychology of Time that Will Change Your Life. New York: Free Press.

Zimbardo, Philip G., Kelli Keough, and John N. Boyd. 1997. “Present Time Perspective as a Predictor of Risky Driving.” Personality and Individual Differences 23 (6): 1007–1023.

Citation

Albright, Robert and John McDermott. 2015. “Time Perspective and the Practice of Financial Planning.” Journal of Financial Planning 28 (1): 46–52.