Journal of Financial Planning: January 2013

Executive Summary

- Employee stock options (ESOs) are often used to compensate employees other than top executives; however, ESOs are complex and not well understood by employees.

- In a study of 210 ESO recipients from five companies, we found employees often value their own options based on simple mental shortcuts, or anchors, that make subjectively judging value easy, but they typically misestimate the true value of ESOs. Options are exercised in the future, so a judgment that incorporates the time value of money leads to higher quality, and often higher dollar, estimates of their value.

- Using actual employees’ subjective estimates of the value of their ESO holdings, we show companies can influence subjective valuations of stock options by educating employees about valuation techniques that incorporate the time value of money. In an experiment using graduate business students who value hypothetical ESOs, we demonstrate that the type of training provided to employees matters.

- Companies that invest in ESO education programs will benefit from more efficient and effective use of ESOs as part of compensation packages in recruiting, retaining, and motivating employees.

- Financial planners can help both their clients who receive ESOs and the companies that issue ESOs to understand the underlying components of an option-pricing estimate.

Susan P. Convery, Ph.D., CPA, CMA, is a professor of practice at Michigan State University where she teaches principles of management accounting and government and nonprofit accounting. She earned her Ph.D. from Michigan State University and co-authored five editions of Accounting for Governmental and Nonprofit Entities by McGraw-Hill.

Anne M. Farrell, Ph.D., CPA, CGMA, is the PricewaterhouseCoopers Endowed Assistant Professor at Miami University. Her Ph.D. is from Michigan State University. She was the manager of corporate financial reporting for Gannett Co. Inc., an analyst for the Hearst Corporation, and an auditor with Deloitte, Haskins & Sells.

Susan D. Krische, Ph.D., CA, earned her Ph.D. from Cornell University and holds a Kogod Research Professorship at American University. Her research investigates how investors and analysts use financial information. She has served as an academic fellow at the Securities and Exchange Commission and worked for Ernst & Young (Clarkson Gordon) as a CA in Canada.

Karen L. Sedatole, Ph.D., earned her Ph.D. from the University of Michigan and currently holds joint academic positions at Michigan State University and Wake Forest University. Previously, she was a systems consultant working on the design and implementation of customized client information systems used in forecasting and planning.

Many companies use employee stock options (ESOs) to attract, retain, and motivate their employees (Elson 2003). At one time, ESOs were considered too sophisticated a form of pay for rank-and-file employees, and grants were usually limited to the CEO and other C-Suite executives. More recently, the use of ESOs has spread to employee compensation packages at many levels within companies.

Yet, ask employees who receive ESOs what the options are worth, and you’re likely to receive a variety of answers. Some question whether companies truly benefit from granting ESOs because of the complications involved in valuing them (Reilly et al. 2003; Watson Wyatt 2003). Others make their opinions quite clear: “[S]tock options are bafflingly complex financial instruments … poorly understood by both those who grant them and those who receive them.” (Hall 2000, p. 123)

Co-authors Farrell, Krische, and Sedatole conducted a research study (2011) to better understand how employees estimate the value of their stock option compensation.1 Research in psychology that studies how people cope with complicated decisions predicts that employees will tend to use simple mental shortcuts, or anchors, to value stock options unless trained to use more sophisticated techniques. Consistent with this prediction, results of the Farrell et al. study show that approximately one-third to one-half of their employee and graduate business student research participants used these simple anchors to value their ESO holdings. However, the study also showed that by applying particular training methods, companies can encourage their employees to apply more sophisticated techniques to value their ESOs and, by doing so, can significantly increase the value employees see in their ESOs.

In this paper, we’ll offer a brief primer on stock options and ESOs in particular, and outline the importance of ESO valuation from the employee’s and company’s perspectives. We’ll then describe the Farrell et al. (2011) study and discuss its implications for Certified Financial PlannerTM (CFP®) certificants.

Stock Options Basics: A Quick Refresher

A stock option is a right to buy a share of company stock for an exercise price (also referred to as a strike price) that extends for a period into the future (the exercise period), but then expires (the expiration date). If the stock price increases during the exercise period, the option increases in value. A person buys an option from a seller, who agrees to sell the stock to the buyer for the exercise price if and when the buyer chooses to exercise the option. As the market price of the underlying stock increases or decreases, the value of the option can swing from being “in-the-money” (the exercise price is less than the stock price) to being “underwater” (the exercise price is more than the stock price).

At the point when the option holder decides it is advantageous to exercise the in-the-money option (who would exercise an underwater option?), he or she can buy the share of stock at the exercise price and immediately resell it for the current market price, making a profit of the difference between the stock and the exercise prices. Alternatively, the option holder can trade the option in one of many exchanges, or can let it expire without exercising it (Broadie and Detemple, 2004).

Valuing financial instruments that derive their value from the change in price of the underlying asset (that is, derivatives) is a complex task. A sophisticated model, the Black-Scholes option-pricing model, was developed to mathematically show how option values are affected by the exercise price, the underlying stock price, the extent to which that stock price changes over time (volatility), the time remaining until the option expires, and market risk-free interest rates. (For a discussion and examples of the Black-Scholes model, see Hill and Stevens, 2002). Further complicating option valuation is the tax treatment of the gain or loss on the exercise, which depends on many factors and is beyond the scope of this article.

What makes an employee stock option different from one traded on option exchanges is that a company is awarding the option to an employee as an incentive to join the company, to work toward increasing the company’s stock value, or to remain employed with the company. Hence, ESOs are often included as part of employee compensation packages.

When ESOs are granted to employees, the exercise periods may be five to 10 years (rather than the frequently shorter terms of tradeable options), and the employee usually cannot exercise the option until a certain time has passed (the vesting period). In addition, ESOs may include contractual obligations (“trading restrictions”) forbidding the employee to trade the options on open markets or sell the stock for a certain period after an option is exercised. Provisions also may exist to award additional options when some are exercised (known as “reloading”; Sun, 2011). Employee stock-option holders also differ from typical stock-option holders in that (1) they typically have a larger percentage of their total wealth tied to the company’s performance, both in terms of stock and ESOs held and by virtue of their employment with the company (they are less diversified), and (2) the tax effects on both the employee and employer are important in the decision to use stock options as a form of compensation.

Valuing Employee Stock Options: The Employee Perspective

Employees who receive stock options as part of their compensation packages must place a value on those options to calculate their total compensation. It is a challenge for employees to understand how much a stock option is worth because of the many factors that affect stock option value.

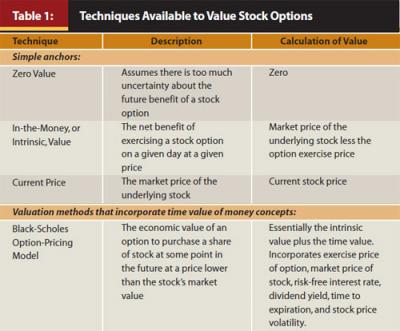

When faced with complex mental tasks, people often reduce the effort involved by ignoring potentially important pieces of information. Specifically, they often reduce the number of pieces of information considered and the steps to process that information and, instead, rely on simple anchor values (Tversky and Kahneman, 1974). In the case of employee stock options, this means some employees may simply assign a zero value to the option until the option vests, or if the option is underwater. Other employees may estimate ESO value at the in-the-money, or intrinsic, value (current stock price less the exercise price). Finally, others may estimate the option value to be equal to the current market price of the underlying stock. Although simple and not challenging to compute, these estimates underweight (or disregard) the stock price volatility, time to expiration of the option, and risk-free interest rate components of ESO value.

The use of simple anchors may lead to biased valuations, which in turn, reduce the incentive effects of ESOs and result in an inefficient use of ESO compensation by companies (see Table 1). When employees misestimate the value of their own stock options by failing to consider the time value of those options, it negates the incentive effects the company hoped to gain by issuing ESOs. On the other hand, if employees incorporate a fuller set of information that captures the time value of the options, estimates of value may be positive even when the options are unvested or underwater, enhancing the incentive effects of the ESOs.

Think of a vested option for a stock that is currently trading at $50. If the exercise price is $49, it’s relatively easy to see that the in-the-money option has some value to the employee: at a minimum, the employee can earn $1 a share by exercising the option and immediately selling the stock (less Uncle Sam’s share, of course, as well as a trading commission).

If the exercise price is $51, the employee would lose money by exercising the underwater option given the current stock price of $50. However, if the option doesn’t expire for several years, there is some chance that the stock price will increase to more than the $51 exercise price and the employee will later be able to benefit from exercising the option. How likely that is depends on the expected rate of return (is it reasonable to expect that the stock price will grow?), the volatility of the stock price (how much uncertainty is there about that growth?), and how long the option has remaining before it expires (how much time does the stock price have to grow?).

Employees who use simple anchors in valuing stock options fail to appreciate that options are a long-term reward, and if stock prices are low today, they may rebound by the time the option is exercised in four, five, or even 10 years (Hill and Stevens, 2002). Thus, a more sophisticated value of the option will consider the time value of money as well as other personal economic factors, such as an employee’s tolerance for risk, ability to diversify his or her investment portfolio, and the employee’s tax rate.

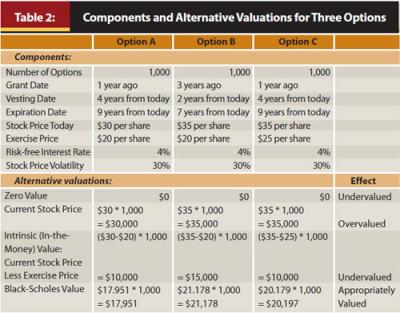

Let’s look at an example in Table 2 of three different options, A, B, and C, and the alternative values an employee could assign to each one. The components to be considered for each option are provided in the table.

An employee who fails to understand how options work could significantly undervalue or overvalue the option. At one extreme, perhaps because the option is not yet vested, the employee may assign zero as a value for each option. This reflects an undervaluation because it ignores the future potential for exercising the option. At the other extreme, the employee may mistakenly value the option at the current stock price, $35,000 for Options B and C, and $30,000 for Option A. This reflects an overvaluation of the option because it ignores the cost of exercising the option (the exercise price).

A somewhat more sophisticated employee will recognize that the value of the option comes from the right to buy the stock for a price that is lower than the going rate. A fairly simple calculation an employee may make is to compute the intrinsic value by taking the difference between the current stock price and the amount the employee would have to pay to exercise the option. Estimating value in this way leads to Option A and C being valued at $10,000, and Option B at $15,000. While this valuation strategy recognizes the intrinsic value of the option, it fails to consider the fact that the stock price will change between today and the option exercise date, which may lead to a greater intrinsic value in the future; that is, the employee is ignoring the time value of the option.

If the employee applies the Black-Scholes valuation technique that incorporates all the information available, including the time value that comes from the possibility that the stock price will increase by the exercise date, he or she would value the option at a much higher amount than the intrinsic value: an extra $7,951 for Option A, $6,178 for Option B, and $10,197 for Option C. Note that the option value will always be greater than the intrinsic value as the time value portion is always positive. (The calculations of the Black-Scholes model are not provided here; see Hill and Stevens, 2002, for more information on the specifics of this valuation technique.)

Granting Employee Stock Options: The Company Perspective

The greater the value an employee places on the stock option, the more likely the company realizes the ESO incentive benefits it desires. Because of this, some companies take various steps to encourage their employees to appreciate the full value of their ESOs. For example, Google established a “Transferable Stock Option” program in which employees can sell their ESOs to contracted financial institutions (Official Google Blog, 2006). The company believed that the program would make the value of stock options much more tangible to employees by showing that financial institutions were willing to pay more than the intrinsic value for their ESOs. Other companies, however, have expressed reluctance to provide ESO education, in part because of concerns over the potential liability associated with discussing possible future stock prices (Hodge et al., 2009).

A company’s decision to grant ESOs is presumably based on a cost-benefit analysis. By granting ESOs, the company incurs an opportunity cost, in that the company could have instead raised capital by selling the stock option to outside investors in the option market. This opportunity cost is reasonably estimated by the Black-Scholes option-pricing model, which establishes the fair market value of a stock option traded on the exchanges.

We have already discussed the benefits a company can receive from granting ESOs, in terms of attracting, motivating, and retaining employees. Quantifying these benefits is challenging, but could be best captured by the amount it would take in cash compensation to achieve certain desired outcomes. In other words, what amount of cash would the company need to spend to attract new employees, retain them, maintain their job satisfaction, and motivate them to work hard to increase profits and ultimately higher stock prices? Other benefits of issuing ESOs to compensate employees rather than salaries and bonuses include conserving cash and the intangible benefit of making employees equity owners of the company.

In sum, for ESOs to be an effective means of compensating employees, the benefits of offering ESOs must exceed the employer’s costs. Importantly, the benefits derived from increased employee attraction, retention, satisfaction, and motivation critically depend on the employees’ perceptions of the value of their ESOs. Only if employees perceive there to be value in the ESOs, including those underwater or unvested, will companies be able to make effective and efficient use of ESOs as incentives in employee compensation packages.

Research on Employees’ Subjective Valuations of Their ESOs

To gain a better understanding of how employees estimate the value of their stock-option compensation, co-authors Farrell, Krische, and Sedatole conducted a research study to examine the subjective values employees place on their ESO holdings, and the related impact of educating employees in more sophisticated option valuation techniques. The study analyzed real-world employees’ option valuations, as well as valuations of hypothetical options made by graduate business students.

Findings from Real-World Employees

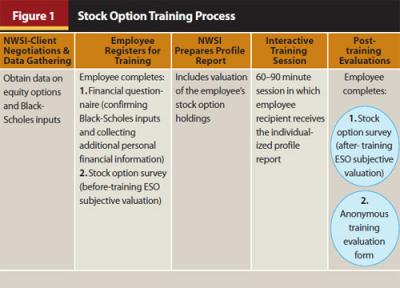

Using data from Net Worth Strategies Inc. (NWSI), a national provider of decision support for equity compensation, the authors analyzed subjective ESO valuations made by 210 recipients of stock options from five companies. These employees received ESOs from their employers and participated in ESO training programs conducted by NWSI (see Figure 1). We were granted access to this data on an aggregate basis under a confidentiality agreement. The companies were large, with market capitalization between $330 million to more than $15 billion, and the employee participants were compensated in the top 10 percent of all employees in their companies.

Employee participants were first surveyed about their assessment of the value of their own ESO holdings. The survey included the following questions that required employees to indicate on a scale of 1 to 5 how strongly they agreed with each statement:

- My stock options and restricted stock encourage me to work harder to contribute to the financial performance of the company.

- My stock options and restricted stock encourage me to continue my employment with the company.

- I am confident I can make timely and tax-efficient decisions regarding my stock options and restricted stock.

The survey also asked the following questions that required employees to assess the value of their options holdings: - If my company stock price were to increase 20 percent, the value of my option holdings would increase about what percentage?

- Of my total investment assets, my total stock option holdings and company stocks are about what percentage?

- If I were to leave the company today, the value of options and restricted stock I would forfeit would be about what amount?

Employees were also asked about restricted stock holdings, but in fact, few employees held any restricted stock.

Employee participants then attended a 60–90 minute interactive group seminar in which they learned the fundamental concepts of option valuation according to the Black-Scholes option-pricing model, which included the time-value component of option valuation (for example, the concept that underwater options still have value because they may become in-the-money at some point before expiration). Available to the seminar participants were individualized equity compensation profile reports prepared by NWSI, based on company- and employee-provided information. The reports included concepts about ESO valuation and definitions of the intrinsic- and time-value components of ESO value, and used numeric examples based on each employee’s own ESO holdings to illustrate the concepts. Training, therefore, included both cognitive feedback about option-pricing concepts (the pieces of information needed to compute ESO value and how to combine that information to form a judgment of value) and outcome feedback about the model-based estimate of the ESO value (numeric estimates of value based on the option-pricing concepts). After training, 124 of the employees completed an optional second copy of the stock option survey and an anonymous training evaluation form.

We found that before training, 30 percent of employee participants relied on the three simple anchors to value their stock option holdings (zero value, intrinsic value, or the current price of the underlying stock). Our research design categorized employee valuations based on whole-portfolio assessments, so it is likely this percentage is much higher because of employees valuing some part of their portfolio on a simple anchor and other parts on other methods. After completing the ESO training program, only 23 percent of employee participants relied on the anchors. This decrease in use of simple anchors is significant; however, we further explore the reasons for this change in the later section on the findings from the graduate business students’ experiment where we could precisely measure whether they used simple anchors or incorporated time-value of money concepts.

With respect to employees’ subjective estimates of ESO value, we measured this both before and after completion of the training program using the last question on the stock option survey (If I were to leave the company today, the value of options and restricted stock I would forfeit would be about what amount?).

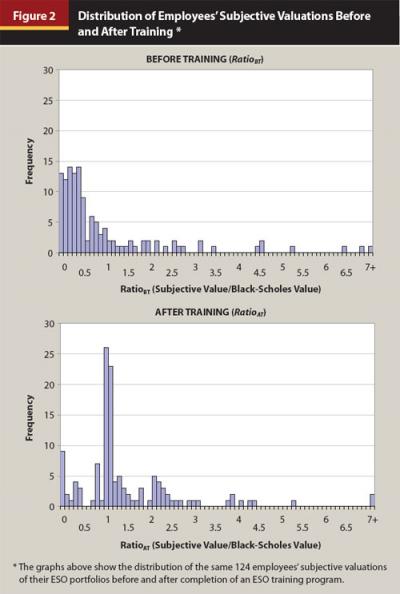

We divided each employee’s subjective estimate of the value of his or her ESO portfolio by the value computed using the Black-Scholes option-pricing model, and call this the computation ratio. We assumed that the Black-Scholes value is a reasonable estimate of the company’s cost of issuing options to employees rather than to the securities markets (although certainly other estimates of company cost are possible). A ratio lower than 1.0 indicates that an employee’s subjective estimate of ESO value is lower than the company’s cost of issuing those options, and a ratio higher than 1.0 indicates that the employee’s subjective estimate of value is higher than company cost. A higher ratio, then, suggests that the employer will capture higher value because of higher employee subjective valuations, an issue addressed later regarding employee perceptions of motivation and loyalty. The distribution of the ratio measure across the 124 participants who provided estimates of value both before and after completion of the training program is shown in Figure 2.

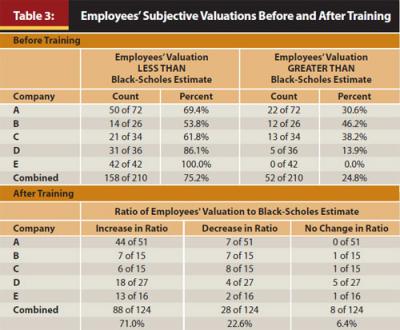

Before training, 75.2 percent of the participants across the five companies reported a valuation of their option holdings that was lower than the Black-Scholes value, while only 24.8 percent reported values higher than Black-Scholes (see Table 3). As a result of the training, 71.0 percent of employees increased their subjective valuations (that is, their ratios were higher after training), while only 22.6 percent decreased their valuations and only 6.4 percent did not change. Overall, then, training not only changed the way most employees valued their option holdings by moving them away from the use of simple valuation anchors, but increased the values they placed on their ESO holdings.

Our study also found evidence that there are motivation and loyalty benefits that accrue to companies that issue ESOs. Employees reported being motivated by their stock options when responding to the statement, “My stock options and restricted stock encourage me to work harder to contribute to the financial performance of the company.” In addition, employees reported a high degree of loyalty to the company because of their ESOs when responding to the statement, “My stock options and restricted stock encourage me to continue my employment with the company.” Further, average responses to both of these statements increased after employees completed the ESO training program.

Findings from Graduate Business Students

We followed up our analysis of this real-world data with an experiment using 196 masters-level business students, whom we assumed were a reasonable substitute for, and perhaps even better-educated in ESO valuation than, real-world ESO recipients. Student participants valued a hypothetical ESO grant before training, and then revalued that grant as well as two additional grants after training. Training came in the form of a condensed educational program modeled after the NWSI seminar, but which included either cognitive feedback or outcome feedback about their hypothetical ESO holdings, as described earlier.

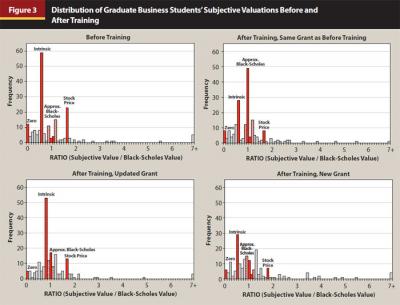

With respect to the use of the three simple valuation anchors, we can measure this much more precisely with the student participants because they all valued the same hypothetical ESOs rather than differing portfolios of ESOs. We found that before training, 46.9 percent of the students used one of the three valuation anchors. After training, however, this percentage fell to 19 percent to 30 percent for the three different hypothetical ESOs.

With respect to subjective valuations, we found the same pattern of results we found with employees. Before training, 64.9 percent of the students valued the hypothetical ESO below the Black-Scholes cost, while the remaining 35.1 percent reported values higher than cost. After training, subjective valuations increased for all three hypothetical options valued. Distributions of students’ subjective valuations relative to the Black-Scholes cost (ratio) for all three hypothetical ESOs are shown in Figure 3.

In addition, with the student participants we learned that subjective valuations of the hypothetical options are affected differently by the outcome feedback and cognitive feedback components of the training program. Student participants’ subjective valuations move away from those based on simple anchors and, on average, increase when training includes outcome feedback. Moreover, these improved valuation judgments are more likely to persist for subsequent valuations of different hypothetical ESOs when participants’ training includes cognitive feedback.

Finally, we asked the students what ESO valuation factors they found important when making their valuations to understand why valuations changed with training. We found that those who relied on simple valuation anchors focused on stock price and exercise price, while those who used more sophisticated valuation methods incorporated more time-value factors into their subjective estimates of value (such as stock price volatility, time to expiration, etc.).

Overall, cognitive feedback provides participants a better conceptual understanding of how the time value of money affects stock-option value. The implication for a company designing educational programs is that cognitive feedback could be more effective in the long term in accomplishing the incentive goals of an ESO program than training that merely provides numerical outcome feedback regarding the Black-Scholes option-pricing valuations.

Relevance to CFP Professionals

Corporate managers should know that educating their employees about sophisticated methods of valuing stock options is in the best interests of both the company and the employees (Hill and Stevens, 2002). However, communicating with employees about their equity plans is considered one of the most challenging aspects of offering equity compensation (PricewaterhouseCoopers 2005). Companies are often reluctant to provide ESO education, in part because of concerns over the potential liability associated with discussing possible future stock prices (Hodge et al. 2009). Because of these challenges and concerns, there is a distinct role for professional financial planners to play in the education of clients who receive ESOs.

While there are applications for valuing options available for computers and smartphones, CFP professionals are uniquely qualified to help clients understand the components underlying the numeric value of their ESOs and to help them estimate these components and combine them in option-pricing estimates.

A significant portion of the “Employee Benefits Planning” topic covered in the CFP Board exam is on employee stock options, so financial planners with this certification have demonstrated knowledge useful for advising clients about valuing stock options, determining when to exercise those options, and recognizing the tax effects of doing so. As such, CFP professionals are in a position to educate individuals about not just ESO valuation amounts, but also the process of how to integrate the time-value component of ESO value into those amounts. As this research study shows, education about the qualitative process of valuing stock options, rather than just providing quantitative information about option values, can lead employees to better judgments about ESO value, about their compensation, and about their personal portfolio of investments.

Educating company management about how their employees are likely to value stock options will assist them in deciding whether to offer stock options as part of a compensation package. While many major companies may obtain these services from compensation consulting firms, small- to medium-sized firms often cannot afford the cost of such services, opening the door for CFP professionals to provide them.

Understanding the value of their ESOs has long been difficult for employees, and analyzing the costs and benefits of ESO programs has never been easy for employers. However, these tasks are even more difficult when markets are volatile and investors’ portfolio returns fluctuate dramatically over short periods. CFP professionals can be an invaluable resource to employees and companies that need to do analyses to better understand ESO value in the long term.

Endnotes

- This paper is based on the collaborative research paper “Employees’ Subjective Valuations of Their Stock Options: Evidence on the Distribution of Valuations and the Use of Simple Anchors,” by Anne M. Farrell, Susan D. Krische, and Karen L. Sedatole, published in Contemporary Accounting Research, 2011, Vol. 28, No. 3 (Fall): 747–793.

References

Broadie, Mark, and Jerome B. Detemple. 2004. “Option Pricing: Valuation Models and Applications.” Management Science 50, 9 (September): 1145–1177.

Elson, Charles. 2003. “What’s Wrong with Executive Compensation?” Harvard Business Review 81, 1 (January): 5–12.

Farrell, Anne M., Susan D. Krische, and Karen L. Sedatole. 2011. “Employees’ Subjective Valuations of Their Stock Options: Evidence on the Distribution of Valuations and the Use of Simple Anchors.” Contemporary Accounting Research 28, 3 (Fall): 747–793.

Hall, Brian J. 2000. “What You Need to Know About Stock Options.” Harvard Business Review 78, 2 (March/April): 121–131.

Hill, Nancy Thorley, and Kevin T. Stevens. 2002. “Showing Employees the Value of Their Stock Options.” Strategic Finance-Montvale 83, 9 (March): 44–47.

Hodge, Frank, Shiva Rajgopal, and Terry Shevlin. 2009. “Do Managers Value Stock Options and Restricted Stock Consistent with Economic Theory?” Contemporary Accounting Research 26, 3 (Fall): 899–932.

Official Google Blog. 2006. “About Transferable Stock Options.” http://googleblog.blogspot.com/2006/12/about-transferable-stock-options.html.

PricewaterhouseCoopers. 2005. Trends in Times of Uncertainty: 2005 Global Equity Incentives Survey. New York: PricewaterhouseCoopers LLC.

Reilly, Mark, et al. 2003. “A Model Executive Compensation Process.” Trends+ Issues: A 3C Publication 2 (Quarter 1).

Sun, Leo. 2011. “Employee Stock Option Basics.” InvestorGuide.com, accessed May 5, 2012,

www.investorguide.com/igu-article-502-employee-stock-options-employee-stock-option-basics.html.

Tversky, Amos, and Daniel Kahneman. 1974. “Judgment Under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases.” Science 185, 1124 (September): 1127–1128.

Watson Wyatt Worldwide. 2003. Changing the Way America Gets Paid: The Fall of the Stock Option and the ‘Correcting’ Impact on Compensation. Washington, D.C.: Watson Wyatt Worldwide.