Journal of Financial Planning: February 2017

Mark J. Warshawsky, Ph.D., is a visiting senior fellow at the MIT Golub Center for Finance and Policy, president of ReLIAS (Retirement Lifetime Income and Asset Strategies) LLC, and a senior research fellow at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University. He is the author of more than 150 scholarly articles and four books, many in the areas of retirement, investments, and insurance. He previously served as assistant secretary for economic policy at the Treasury Department and as a member of the Social Security Advisory Board. This work is based, in part, on a section of an unpublished monograph on reverse mortgages by Mark J. Warshawsky and Tatevik Zohrabyan, supported by the MIT Golub Center for Finance and Policy.

Acknowledgements: The author thanks Michael Leahy for his research assistance.

Executive Summary

- This paper reviews how reverse mortgages work, with a focus on costs, taxation, and possible use in enhancing lifetime retirement security through tenure payments.

- A recent article in the financial planning literature found that tenure payments from a reverse mortgage effectively and efficiently balance income and bequest needs of a retired household.

- For those retired households who have both significant retirement assets and housing equity, the question remains whether they should use reverse mortgages based on their housing equity or immediate life annuities based on their retirement assets. The answer lies, in part, in an empirical analysis done here with note of costs and current market conditions, using standard calculators.

- Results show that for three timeframes with different interest rate levels, the life annuity produced higher income for individuals of almost all ages and both genders in retirement, while for couples, the reverse mortgage produced generally higher incomes, although the income from the annuity improves relatively when the age spread among the couple widens and as they are older.

An increasingly dominant thought in the professional financial planning literature is that there should be a prominent role for immediate life annuities purchased with retirement assets in retirement income strategies. Yet an alternative strategy exists—tenure payments from a reverse mortgage, also known as the HECM (home equity conversion mortgage), based on the value of an owner-occupied house.

The main subject of this paper is a realistic comparison of reverse mortgages and life annuities. First, an explanation and review of how reverse mortgages work is offered. Because the literature on the various types, uses, and terms of life annuities already exists, that is not reviewed here, but the interested reader can see, for example, Pang and Warshawsky (2009), Warshawsky (2013 and 2016) and Blanchett (2014). Then, one recent comprehensive analytical study of how reverse mortgages might best be used during retirement is reviewed. Finally, the current terms are compared; that is, incomes that would result from tenure-payment reverse mortgages on housing with incomes from immediate life annuities from retirement assets. Life annuities were somewhat favored in this comparison, particularly for individuals, and should be used by retired households with significant financial and retirement asset holdings instead of reverse mortgages if there is a desire or need to increase retirement incomes.

The HECM Product

The home equity conversion mortgage (HECM) is the Federal Housing Administration’s (FHA) reverse mortgage product and program.1 It enables older homeowners to withdraw some of the equity from their homes, either immediately or later in life (through a line of credit), and either in a lump-sum, over a period of time, or for as long as the owner (or spouse) lives in the home. Unlike a home equity loan or a second mortgage, HECM borrowers do not have to repay the HECM loan until the last surviving borrower dies, sells the home, or has not used the home as their principal residence for more than a year (e.g., after entry into a nursing home) or fails to meet the obligation of the mortgage, such as paying property taxes and insurance.

To be eligible for a HECM, the FHA requires that the homeowner be 62 years of age or older (as of August 2014, a younger, non-borrowing spouse is allowed), own the home outright, or have a relatively low mortgage balance that can be paid off at closing with proceeds from the reverse loan, and have the financial resources to pay ongoing property charges (or put those resources aside). The home must be a single-family home, or a two- to four-unit home with one unit occupied by the borrower; condominiums and manufactured homes may also be eligible.

When the home is sold or no longer used as a primary residence, the cash payments, interest, and other HECM finance charges must be repaid. Any proceeds from or value of the home beyond the amount owed on the HECM belong to the owners, or if deceased, the surviving spouse or estate. No debt is passed along to the estate or heirs. It is a non-recourse loan. Therefore, if the value of the house declines over the lifetime of the retired homeowner, or the cash payments extend for a long time, interest rates increase, and so on, it is possible that the deceased or relocated borrower will pay back less than what he owes.

By FHA rules, the amount available for borrowing (the “eligible benefit”) varies and depends on the age of the youngest borrower or non-borrowing spouse, the current expected interest rate, and the lesser of appraised value or the HECM mortgage limit of $625,500. In general, the older the homeowners, the more valuable their home, and the lower the interest rate, the higher the loan that is available.

In the past, availability did not depend directly on income, credit history, or health. Beginning in April 2015, however, the FHA requires lenders to assess and document a borrower’s ability to pay—particularly focusing on property taxes and insurance—before originating a loan, following minimum credit, debt, and affordability standards. Borrowers failing these standards can be required to set aside a portion of their available principal in a lender-managed escrow account to cover future tax and insurance expenses.

For adjustable interest rate mortgages, the following are the possible payment plans:

Tenure (“life” annuity): equal monthly payments as long as at least one borrower lives and occupies the property as a principal residence.

Term (“fixed period” annuity): equal monthly payments for a fixed period of months selected.

Line of credit: unscheduled payments or in installments, at times and in an amount of the homeowner’s choosing until the line is exhausted. A unique aspect of a HECM line of credit is that it rises over time by the interest rate on the line.

Modified tenure: combination of line of credit and scheduled monthly payments for time of residence.

Modified term: combination of line of credit and term.

Single disbursement lump sum: a single payment at mortgage closing (this is the only payment plan available for fixed-rate mortgages). The maximum disbursement is restricted to 60 percent of the eligible benefit or the various closing costs plus 10 percent of the benefit. This restriction was put into place in 2013 to reduce loan defaults, which were more common with this payment option.

The line of credit option is now the most popular payment plan, according to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), chosen either alone (68 percent) or in combination with the term or tenure plans (20 percent). According to 2016 HUD statistics2, in June 2016 there were 591,000 HECM loans outstanding based on $145.7 billion in property value; this market has been slowly shrinking in recent years.

Mortgage insurance issued by the FHA is a mandatory part of the HECM product. The premium on it pays for the federal guarantee that the lender is protected against credit risk and is part of the product design (non-recourse) that the borrower will never owe more than the value of the home.

Similar to those found in traditional forward mortgages, HECM closing costs include an origination fee to the lender (for processing the HECM loan, a lender can charge the greater of $2,500 or 2 percent of the first $200,000 of the home’s value plus 1 percent of the amount over $200,000; HECM origination fees are capped at $6,000); third-party fees such as appraisal, title search and insurance, surveys and inspections, recording fees, mortgage taxes and credit checks; and if less than 60 percent of the available funds are accessed in the first year of the HECM, the upfront mortgage insurance premium equal to 0.50 percent of the home value.

A fee for mandatory counseling (about $125) is also charged to the potential borrower. Fees that accrue over the life of the loan include interest expense, a monthly servicing fee of up to $35, and mortgage insurance premium equal to 1.25 percent of the outstanding loan balance. The monthly adjusting interest rate is commonly set at the one-month London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR) plus a lender’s margin averaging 2.5 percent (as reported by the National Reverse Mortgage Lenders Association; nrmlaonline.org), with a lifetime cap of the initial interest rate plus 10 percent. The adjustable interest rate can now be either the one-month LIBOR, or the one-month or one-year constant-maturity Treasury bond (CMT) for monthly adjustment, or the one-year LIBOR or one-year CMT for annual adjustment.

The eligible benefit amount is based on the age of the youngest member of the borrowing household, the home value (up to $625,500, which is the current FHA 203(b) limit), and the loan’s expected rate. The latter for adjustable-rate loans is equal to the lender’s margin and the 10-year LIBOR swap rate (note that this differs from the LIBOR interest rate actually charged on the mortgage; if one of the CMTs are used for the variable rate, then the 10-year CMT is used for the expected rate).

More specifically, the eligible benefit is the product of the home value and a principal limit factor, less the various initial cash payments, liens, upfront mortgage insurance, closing costs, and funds set aside for monthly servicing fees. For example, on July 15, 2016, for a $400,000 home owned by a 75-year-old individual, the principal limit factor based on a loan margin of 2.5 percent and an expected rate of 1.29 percent (10-year LIBOR swap rate) is 0.614, so the initial principal limit is $245,600. Further assuming $2,000 in initial mortgage insurance premium, an origination fee of $6,000 (the maximum allowed), closing costs of $2,322 (depends on location), and a servicing set-aside of $5,111.40 (the present value of $30 monthly for 25 years discounted using the expected rate plus the ongoing mortgage insurance premium of 1.25 percent), gives an eligible benefit amount of $230,116.60.

The term payment and tenure payment options pay out assuming a discount rate equaling the expected rate, the margin, and the ongoing mortgage insurance premium. On July 15, 2016, this was 5.04 percent. (Recall that the loan itself carries a variable rate based on LIBOR, which was 0.48 percent on that date.)

The tenure option calculates monthly payments as if the borrower will reach age 100. Regardless of the actual loan balance, payments continue even past age 100, as long as the borrower is living in the property, so there is an element of life contingencies in the HECM with this payment option. Insurance companies issuing immediate life annuities in July 2016 would have assumed a lower life expectancy than 100 for the 75-year-old individual in the previous example, but would also likely have used interest rates lower than 5 percent. Therefore, on net, it is not clear whether the life annuity from the commercial market or the tenure HECM would give higher lifetime monthly payments on the same asset value.

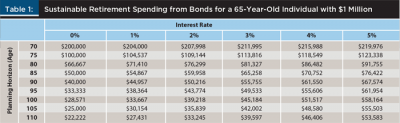

Table 1 provides selected principal limit factors under the program rules as of July 15, 2016 by borrower age at origination and expected rate.

The HECM principal limit factors (PLFs) provide the percent of maximum claim amount (MCA) allowable in total cash draws, given the age of the borrower(s) and the expected interest rate of the loan. The PLFs presented here are in decimal form (e.g., 0.562 equals 56.2 percent).

PLFs do not change for borrowers older than the age of 90. Although such borrowers are still eligible for the HECM, they are not eligible for any increase in PLF. All effective rates below 5.0 percent have the same PLF as for the 5.0 percent effective rate, by borrower age. MCA is the lesser of 98 percent of the property’s appraised value at the time of the loan application, or the applicable FHA loan limit.

Tax Treatment

The following discussion gives some consideration to the relative tax treatment of HECMs and life annuities.3 Regarding the tax treatment of reverse mortgages, the IRS Publication 936 (www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/p936.pdf) says:

Depending on the plan, your reverse mortgage becomes due with interest when you move, sell your home, reach the end of a pre-selected loan period, or die. Because reverse mortgages are considered loan advances and not income, the amount you receive is not taxable. Any interest (including original issue discount) accrued on a reverse mortgage is not deductible until you actually pay it, which is usually when you pay off the loan in full. Your deduction may be limited because a reverse mortgage loan generally is subject to the limit on home equity debt. That limit is the smaller of: $100,000 ($50,000 if married filing separately); or the total of each home’s fair market value (FMV) reduced (but not below zero) by the amount of its home acquisition debt and grandfathered debt. Determine the FMV and the outstanding home acquisition and grandfathered debt for each home on the date that the last debt was secured by the home.

Davison (2014) proposed using HECMs in a sort of tax and annuity arbitrage as follows: delay claiming Social Security until age 70, avoid any distributions from traditional IRAs, and fund any income gap with the proceeds from the HECM. The idea is to let the IRAs accumulate with their tax-advantaged status on investment earnings and to realize an implicit pricing advantage from the delayed claiming credits Social Security gives because it uses a 3 percent real interest rate and static unisex mortality rates. Of course, if the retired household also has other assets on which it has already paid taxes (which is common for households with IRAs), the above strategy could be alternatively implemented without a HECM. Also, if the household is a single male or a couple, the value of the Social Security claiming arbitrage—that is, the actuarial advantage to delay of claim—is reduced.Based on this, there does not seem to be any tax advantage or disadvantage to a HECM compared to a home equity line of credit, or to a refinanced mortgage. However, as noted by Sacks, Maningas, Sacks, and Vitagliano (2016), the deduction on HECM interest will be lost in many situations. Because interest is not deducted until it is actually paid, and in many circumstances, the home is sold and interest is paid by the estate after the borrower has died and when there is often not that much taxable income generated by the estate, the deduction is often lost. Sacks et al. therefore recommended that the deduction be “recovered” by having the beneficiaries, rather than the estate, sell the home and pay off the reverse mortgage, and then use the deduction to lower their taxable income, if they have substantial income or through extra withdrawals from their own or inherited deductible, traditional IRAs.

Some analysts posit a tax advantage to the HECM over the life annuity because payments from the HECM are not taxed while those from a life annuity are (in part, if they originate from taxable assets, or in whole, if they originate from qualified retirement assets). But this argument ignores the fact that these tax advantages are just extensions of the original tax status of the underlying assets, not from the HECM or life annuity payouts per se. Owner-occupied housing as an asset is lightly taxed from day one and regardless of its eventual use. In particular, the tax treatment is fixed on the underlying assets and any distributions from them will generally share their status, even if formal income payments from them are not made (and without further considering minimum required distributions on qualified assets and IRAs).

Review of a Recent Comprehensive Study

Next, one recent comprehensive study in the literature4 on the use of reverse mortgages for retirement security is reviewed here. This study relied and was based carefully on prior studies and advances methodology; therefore its conclusions may serve as the current view in the field.

Using a sophisticated stochastic and integrated model of variable asset returns, interest rates, inflation, and housing prices, Pfau (2016) evaluated six retirement income strategies that involved spending using a HECM: (1) delay opening a line of credit with a reverse mortgage until all other financial assets (in his analysis, a large IRA) are exhausted; (2) open a line of credit immediately upon retirement and use it to support retirement spending first until the line is exhausted, and then turn to other investments; (3) open the line of credit at retirement and take from it when the investment portfolio experiences a loss; (4) the Salter, Pfeiffer, and Evensky (2012) coordination strategy, with the cash reserve bucket removed, whereby the line of credit is taken or repaid depending on developments in the wealth glide path compared to the plan; (5) the line of credit is opened at the beginning of retirement but it is used at the end only if and when the investment portfolio is depleted; and (6) use tenure payments from the HECM with other spending needs filled in from withdrawals from the investment portfolio.

In his simulation analysis, Pfau assumed a home value of $500,000, a HECM with an interest rate spread of 3 percent (higher than what was used below), and origination and closing costs of $5,000 (lower than was used below), a $1 million IRA invested equally in stocks and bonds, a 25 percent tax rate, a 62-year-old borrower, and current initial interest rates. The stated goal was 4 percent real post-tax initial spending rate (implying a 5.33 percent gross rate of withdrawal initially from the retirement investment portfolio, increased subsequently by the rate of realized inflation). Pfau evaluated the six strategies by the probability of meeting that spending goal, but he also considered the wealth remaining for a bequest.

The fifth strategy produced the highest rate of success across retirement horizons (up to 40 years) for the retirement income goal. Pfau noted that, especially when interest rates are initially low, the line of credit will almost always be larger by the time it is needed than when it is opened later (as in the first strategy, which gave the lowest rate of success among the strategies). The other four strategies fell somewhere in the middle in terms of plan success.

Adding concern for the combined legacy value of the household’s assets, however, produced a somewhat different ordering of optimal strategies. At a horizon of 25 years and longer, the legacy value for the tenure payment option was the highest among the strategies. Pfau stated that this was a combined result of the partial home equity use preserving the portfolio longer, and that eventually tenure payments enter into the non-recourse aspect of the reverse mortgage because income continues even if the loan balance has already exceeded the line of credit. The tenure payment strategy also did well, relative to the other strategies, in the lower percentiles of outcomes.

Pfau concluded his analysis with the observation that strategies that open a line of credit and leave it unused run counter to the objectives of the government and its risk concerns, and therefore may be eliminated in the future by federal rule changes. Hence, the HECM tenure payment option is considered here as the one most appropriate for retired households, in general, that typically have both income and legacy needs from their retirement assets.

Current Terms in the HECM and Immediate Annuity Markets

Roughly speaking, the financial product most comparable to a HECM making tenure payments is a life annuity with a cash refund feature. With the latter, the individual (or couple) pays the insurance company a lump-sum amount, which is dependent on gender and age, and gets a fixed lifetime flow of income in return. If the individual (or couple) dies early, the beneficiaries receive the lump sum less any annuity payments already paid. So if the individual dies relatively soon, most of the lump-sum amount will be available as a bequest. If the individual lives a long time, however, there will be no cash refund.

When borrowing an amount with a HECM with tenure payout, the individual (or couple) gets a fixed lifetime flow of income. If the individual (or couple) dies early, the home loan will be repaid and the remaining amount will go to the heirs. If the individual lives a long time, however, it is less likely that any corpus will remain.

One has to say “roughly speaking” in this comparison for several reasons. Most importantly, obtaining a HECM has significant fixed costs, regardless of the size of the loan (fees of various types of HECMs can approach $6,000 or more). Such a toll may sensibly prevent the use of HECMs for home equity values of $100,000 or less. By contrast, for immediate life annuities, the administrative and sales costs of the product are embedded in the pricing and do not include a fixed amount paid by the investor initially.

Moreover, other cost and value considerations differ between the two approaches. The economic values of these “second-order” differences go in opposite directions. On the one hand, the HECM will likely pay out for a couple of years less, on average, than the life annuity because many households must move out of the home owing to the need for assisted living or nursing home care, to be near children in other locales for their assistance, or for other personal and family reasons. Also, the life annuity payouts are fixed and guaranteed at the time of the lump-sum premium payment—providing certainty. Whereas, the amount eventually owed on a tenure HECM loan is variable and uncertain because of interest rate and housing price movements over time. Finally, the amount of life annuity that can be purchased is practically limitless, given assets available to the household. This is unlike the HECM, which is limited by statutory, regulatory, and administrative constraints. These factors increase the economic value of the life annuity compared to the HECM.

In the opposite direction, there is a higher likelihood of a residual being left to heirs with a HECM because the household gets the benefit of any home price appreciation, but it is protected from home price declines by the limited liability feature of the HECM. (The penultimate section of this article shows a simple illustration of the effects of changing interest rates and house prices on the residual value of the estate using a HECM.)

How these real economic differences net out in terms of utility and value is unknown and analytically would be complex to model and calculate. This paper provides a simple, straight-up comparison of the monthly incomes produced by identical amounts borrowed/annuity single premiums paid for individuals and couples of various ages, from 65 to 85, adjusted only for HECM initial transaction costs.

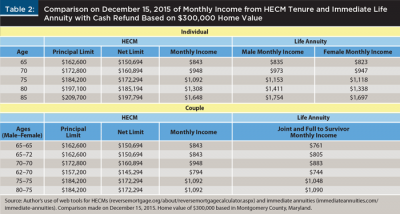

The comparison was conducted on December 15, 2015, using two tools found on the web: (1) the reverse mortgage calculator by the National Reverse Mortgage Lenders Association (reversemortgage.org/about/reversemortgagecalculator.aspx); and (2) an immediate annuity calculator by the insurance broker WebAnnuities (www.immediateannuities.com/immediate-annuities).

Both websites indicated that monthly income amounts shown are estimates; the former because of variable closing costs that differ greatly by geography and varying lender terms; the latter because the monthly income amounts shown are based on several quotes from many large commercial insurance companies. In particular, the retiree might do somewhat better by selecting the lowest-priced mortgage issuer or insurer at the time of the quotes. Immediate life annuities are sold in an active, small, but growing market. According to LIMRA, as reported by Pechter (2016b), fixed immediate annuity sales were expected to exceed $10 billion in 2016, 10 percent to 15 percent higher than 2015 sales.

In an April 15, 2015 online comment on the paper by Tomlinson (2015), Tom Davison said that origination fees from one lender were lower than what was reported by the calculator. He also noted, however, that this tendency was sometimes made up by a higher spread. By contrast, in trade press accounts (see Pechter 2016a), origination fees were indicated to be at the regulatory maximum for the largest lenders, and only by extensive search among obscure lenders and/or sharp negotiation could borrowers get lower fees. So clearly, actual pricing and fees in the HECM market are not transparent and require further investigation. For the purposes of this paper, it seemed reasonable to use the calculator put out by the relevant trade association.

For the HECM, we assumed a $300,000 house in Montgomery County, Maryland, with typical origination and closing fees as well as insurance and administrative fees. The fee for mandatory counseling, however, was apparently not included in the calculator. Note that HECM initial fees, in particular closing costs, vary widely by state, perhaps because of special state requirements or allowances, or market practices and conditions. For the life annuity, for both singles and couples, the cash refund feature was used. And for couples, the joint and 100 percent to survivor feature was used, without, however, deducting the HECM fees from the single premium, which are not relevant to immediate life annuities.5

Table 2 shows the results of the comparison between HECM tenure payments and life annuity payments for the same principal limit amount, that is, after the deduction of fees (as estimated by the tool) for the HECM and none for the life annuity. Stated another way, the HECM monthly payments were based on the net principal limit, and the life annuity monthly income was based on the principal limit shown in Table 2. Note that for couples, the first age is for a male and the second age is for a female; this does not matter for the HECM, but it does for the life annuity, as will be more clearly shown below.

Several things are immediately apparent in the comparison shown in Table 2. The net limits and monthly income produced by tenure HECMs do not differ by individual versus couple, by gender, nor by the extent of the age span between the members of the couple. These variables do, however, influence life annuity pricing, or its obverse, monthly income, for the same initial borrowing/single-premium amount. In general, the monthly income for individuals was lower for HECMs compared to life annuities—particularly for older individuals and males (where mortality considerations are likely more important than interest rates, at least at current low interest rate levels). By contrast, for couples, HECMs produced somewhat higher monthly incomes across all ages and age spreads, although the income from the life annuity improved relatively when the age spread among the couple widens and as they are older.

The income advantage to the tenure HECM for couples was somewhat surprising. It is possible that the FHA believes that when one member of the couple gets sick and needs to move, the other member will also move, losing the independence of the tenure probabilities, and thereby it does not have to “charge” for the joint-and-survivor insurance. By contrast, insurance companies prudently do have to price on the basis of the independence of mortality probabilities. It is also possible that the FHA was not pricing tenure HECMs correctly for couples.

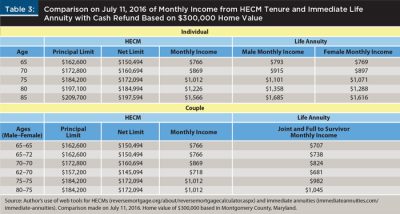

Table 3 presents the same comparison as Table 2, but for July 11, 2016, after the yield on the 10-year Treasury bond fell about 80 basis points. The HECM principal limit did not change because although, in general, lower interest rates increase the principal limit, at the end of 2015 and through 2016, the expected rate was below 5 percent. The net limit declined $200 across the board, apparently because the National Reverse Mortgage Lenders Association, the creator of the tool, believed that some costs (unidentified) were higher. Looking at the variables of interest—monthly income from the HECM and the life annuity—the relationships seen in Table 2 still hold, with a slight improvement in the relative position of the life annuity (at the oldest ages for couples shown, the life annuity gave higher income in Table 3 compared to Table 2), even as levels dropped across the board with lower interest rates.

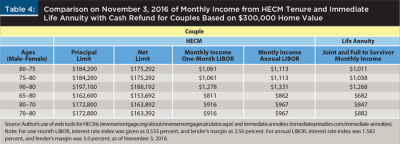

Table 4 shows results for couples, as of November 3, 2016, for older ages and wider spreads of spousal ages. Although the principal limits did not change from earlier dates, the HECM tool as of November 2016 indicated somewhat lower transaction costs and fees, so the net limit was higher, while the interest rate spread for the annual LIBOR was 300 basis points instead of the earlier 250. These changes increased income from the HECM, compared to Tables 2 and 3. Still, life annuity income was in the range of HECM income for couples, particularly at older ages and when the female member of the couple was older than the male.

These results indicate broadly that, for individuals, the implementation of lifetime retirement income strategies can be more effectively (and generally more cheaply) done using immediate life annuities bought with financial assets, than by HECMs based on home equity amounts. The results for couples are more ambiguous, but couples may particularly appreciate that the life annuity pays for life, whereas the HECM only pays for tenure. So for households that have both significant financial and housing assets, the HECM with a tenure payment feature is likely not best used for retirement security for the production of lifetime regular income flows, in contrast to life annuities with a cash refund feature. Although immediate life annuities are currently not widely used by retired households, there appear to be no impediments from them being so used. Hence, the assessment here is relevant to policy analysis and recommendations, as well as to the empirical analysis of the potential HECM market.

End-of-Life Outcomes

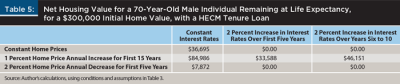

Using a few simple illustrations, some possible end-of-life outcomes using the HECM, instead of focusing on comparative lifetime income flows, were explored here. In particular, the net housing value remaining was examined (that is, gross house value less reverse mortgage payments accumulated with interest), arising from nine economic scenarios at the end of the life expectancies for two cases: (1) a 70-year-old male individual; and (2) a 65-year-old mixed-gender couple.

According to the longevity tool of the American Academy of Actuaries (longevityillustrator.org), based on Social Security data, the life expectancy in the first case was another 16 years, whereas in the second case (last survivor) it was 27 years. The economic scenarios involved different combinations of rising and constant interest rates, and rising, falling, and constant house prices. The initial interest rate conditions and HECM net limits and tenure payments were as of July 11, 2016, as shown in Table 3. Thereafter, interest rates either remained the same, increased by 2 percentage points over the next five years, or remained the same and then increased by 2 percentage points in years six to 10. Home prices either remained the same, declined by 2 percent annually over the next five years, or increased by 1 percent annually over the next 15 years. If the net value went to negative, it was set to zero because the HECM is a non-recourse loan.

Table 5 shows results for the first case, a 70-year-old male individual. In the second case, a 65-year-old mixed-gender couple, in no scenario was there any remaining value, given the longer payout period and the high interest costs, even when rates were flat. For the individual, the largest amount remaining, about $85,000, was when house prices increased and interest rates were flat. In the other scenarios, the remaining amounts were more modest or zero.

Summary and Conclusions

The HECM, a government-sponsored reverse mortgage, is designed to enable elderly homeowners to convert the equity in their homes to monthly streams of income and/or lines of credit. But the considerable up-front and on-going transaction costs reduce the value of the HECM as a way to realize home equity in the most common and simple uses, particularly for relatively modest amounts. The current end result of the financial planning literature is that, on balance, the tenure payment option is the best overall use of the HECM. That payment plan appears to be most consistent with the retirement security policy intent of the program.

A tenure payment HECM, even with high fees, might be appropriate for retired households with both housing and financial assets, if the terms for HECM payments are better than those for life annuities in the commercial market.

Several things are immediately apparent from a comparison of current terms for HECMs and life annuities. The net limits and monthly income produced by tenure HECMs did not differ by individual versus couple, by gender, nor by the extent of the age span in the couple. These variables did, however, influence life annuity pricing, or its obverse, monthly income, for the same initial borrowing/single-premium amount.

In general, the monthly income for individuals was lower for HECMs compared to life annuities—particularly for older individuals and males. By contrast, for couples, HECMs produced somewhat higher monthly income across all ages and age spreads, although the income from the life annuity improved relatively when the age spread among the couple widens and as they are older.

These results indicate broadly that, for individuals, the implementation of lifetime retirement income strategies can be more effectively and generally more cheaply done using immediate life annuities based on financial assets than by HECMs based on home equity amounts. The results for couples were more ambiguous. For households that have both significant financial and housing assets, the HECM with a tenure payment feature was generally not best used for retirement security for the production of lifetime regular income flows, in contrast to life annuities, which are frequently recommended by standard economic analysis.

Future work should focus on the potential use of HECMs among those retired households with some financial assets, but not “too much,” and significant housing equity—that is, those for whom a conventional life annuity based on assets will not produce much retirement income, but a reverse mortgage might.

Endnotes

- Based on the FAQs about HUD’s reverse mortgages (www.portal.hud.gov/hudportal/HUD?src=/program_offices/housing/sfh/hecm/rmtopten, viewed from October 2014 through July 2016); Stucki (2013), and Johnson and Simkins (2014).

- See www.portal.hud.gov/hudportal/documents/huddoc?id=FHAProdReport_Jun2016.pdf.

- Based on the IRS website (IRS.gov) viewed January 14, 2016; Sacks, Maningas, Sacks, and Vitagliano (2016); and Davison (2014).

- A lengthy review of the reverse mortgage literature and bibliography may be found in Warshawsky and Zohrabyan (2016).

- Tomlinson (2015) conducted a similar exercise, but deducted the HECM fees from the annuity premium, apparently used a straight annuity instead of a cash refund annuity, and looked at only age 65 instead of also the older ages where HECMs are more commonly taken.

References

Blanchett, David. 2014. “Determining the Optimal Fixed Annuity for Retirees: Immediate versus Deferred.” Journal of Financial Planning 27 (8): 36–44.

Davison, Thomas C. B. 2014. “Delay Social Security: Funding the Income Gap with a Reverse Mortgage.” Published online by the author, June 23. Available at www.docplayer.net/15689026-Delay-social-security-funding-the-income-gap-with-a-reverse-mortgage.html.

Johnson, David W. and Zamira S. Simkins. 2014. “Retirement Trends, Current Monetary Policy, and the Reverse Mortgage Market.” Journal of Financial Planning 27 (3): 52–59.

Pang, Gaobo and Mark J. Warshawsky. 2009. “Comparing Strategies for Retirement Wealth Management: Mutual Funds and Annuities.” Journal of Financial Planning 22 (8): 36–47.

Pechter, Kerry. 2016a. “The ‘Kosher’ Reverse Mortgage (IV).” Retirement Income Journal 355. Available at www.retirementincomejournal.com/issue/may-26-2016/article/the-kosher-reverse-mortgage-iv.

Pechter, Kerry. 2016b. “AIG Tops Annuity Sales Chart Again.” Retirement Income Journal 370. Available at www.retirementincomejournal.com/issue/september-29-2016/article/aig-tops-annuity-sales-chart-again.

Pfau, Wade D. 2016. “Incorporating Home Equity into a Retirement Income Strategy.” Journal of Financial Planning 29 (4): 41–49.

Sacks, Barry H., Nicholas Maningas, Sr., Stephen R. Sacks, and Francis Vitagliano. 2016. “Recovering a Lost Deduction.” Journal of Taxation April: 157–169.

Salter, John, Shaun Pfeiffer, and Harold Evensky. 2012. “Standby Reverse Mortgages: A Risk Management Tool for Retirement Distributions.” Journal of Financial Planning 25 (8): 40–48.

Stucki, Barbara. 2013. “New Directions for Policy and Research on Reverse Mortgages,” Public Policy and Aging Report 23 (1): 9–13.

Tomlinson, Joe. 2015. “New Research: Reverse Mortgages, SPIAs, and Retirement Income.” Advisor Perspectives. Posted April 14. Available at www.advisorperspectives.com/articles/2015/04/14/new-research-reverse-mortgages-spias-and-retirement-income.

Warshawsky, Mark J. 2013. “Retirement Income for Participants in Defined Contribution Plans and Holders of IRAs: Recent Developments in Immediate Life Annuities and Other Income Products.” Journal of Retirement 1 (1): 12–26.

Warshawsky, Mark J. 2016. “New Approaches to Retirement Income: An Evaluation of Combination Laddered Strategies.” Journal of Financial Planning 29 (8): 52–61.

Warshawsky, Mark J. and Tatevik Zohrabyan. 2016. “Retire on the House: The Use of Reverse Mortgages to Enhance Retirement Security.” MIT Golub Center for Finance and Policy, working paper. Available at www.gcfp.mit.edu/wpcontent/uploads/2016/08/Warshawsky-Retire-on-the-House.pdf.

Citation

Warshawsky, Mark J. 2017. “To Enhance Lifetime Retirement Security, Use Reverse Mortgages or Immediate Annuities?” Journal of Financial Planning 30 (2): 52–60.

Acronym Glossary

CMT: constant-maturity Treasury bond

FHA: Federal Housing Administration

FMV: fair market value

HECM: home equity conversion mortgage

HUD: U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development

LIBOR: London Interbank Offered Rate

MCA: maximum claim amount

PLF: principal limit factor