Journal of Financial Planning: February 2013

Randy Gardner, J.D., LL.M., CFP®, CPA, is a professor of tax and financial planning at the University of Missouri–Kansas City and director of education for WealthCounsel and The Advisors Forum. He also is co-author (with Julie Welch) of 101 Tax Saving Ideas and co-author (with Leslie Daff) of The Closing Wealth Transfer Window. (gardnerjr@umkc.edu)

Leslie Daff, J.D., is a state bar certified specialist in estate planning, probate, and trust law and the founder of Estate Plan Inc., a professional law corporation with offices in Orange County, California, and Johnson County, Kansas. (ldaff@estateplaninc.com)

Julie Welch, CFP®, CPA, is the director of tax and a shareholder with Meara Welch Brown PC in Kansas City, Missouri. (julie@meara.com)

An increasing number of business owners are addressing their human capital needs by hiring independent contractors. Business owners benefit by avoiding the administrative hassles of employing workers and the out-of-pocket costs of payroll taxes and fringe benefits.

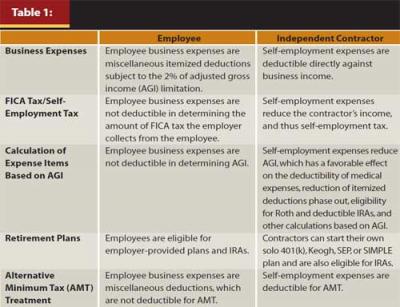

With the jobless rate, although decreasing, still hovering around 8 percent, the number of people willing to work as independent contractors at reasonable rates is high. Furthermore, as Table 1 shows, working as an independent contractor rather than as an employee offers several tax advantages.

The trend toward independent contractors will likely continue as business owners cope with the insurance mandate of President Obama’s Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act by hiring contractors rather than full-time workers.

Disadvantages of Working as an Independent Contractor

Several disadvantages exist, however, when working as an independent contractor. The contractor is responsible for self-employment tax, which is a 15.3 percent rate rather than the 7.65 percent FICA rate collected from an employee, and the contractor may need to pay estimated taxes. The contractor also must prepare a Schedule C or other business tax form to report the income. Finally, small businesses are audited at approximately a 5 percent rate, while the average audit rate for individual tax returns is 1 percent.

Example: Business Betty (BB) and Employee Ed (EE) both gross $120,000 from their work and have $20,000 of business-related expenses. Both are in the 34 percent federal and state marginal tax rate bracket.

A quick comparison of their relative tax situations goes as follows: BB will have net income of $100,000 on which she will owe approximately $14,100 of self-employment tax. Half of this self- employment tax ($7,050) is deductible for income tax, giving BB $92,950 of taxable income and $31,603 ($92,950 x 34%) of income tax, $45,703 ($31,603 + $14,100) when self-employment tax is added on.

EE, on the other hand, has $120,000 of income subject to payroll tax of approximately $8,789 because his entire wage, unreduced by the business expenses, is subject to payroll tax. The $20,000 of expenses must be reduced by $2,400 (2 percent of his $120,000 of AGI), meaning his taxable income is $102,400 ($120,000 – 20,000 + 2,400) and his income tax is $34,816 ($102,400 x 34%). His total tax, including his share of the payroll tax, is $43,605.

Although the independent contractor pays more tax, this calculation is before considering larger retirement plan contributions, home office deductions, and other benefits contractors can claim.

Determining Worker Status

Faced with lost revenue from payroll, income, and unemployment taxes, the federal and state governments have increased their scrutiny of the owner-worker relationship. A person is an employee for FICA and other employment tax purposes if the person is a common-law employee.

The common-law employer-employee relationship exists when the person for whom services are performed has the right (whether or not actually exercised) to control and direct the individual who performs the services—not only as to the result to be accomplished, but also as to how the result is accomplished.

In contrast, if a worker is subject to the direction or control of another merely as to the result to be accomplished by the work and not as to the means and methods by which the result is accomplished, the worker is an independent contractor.

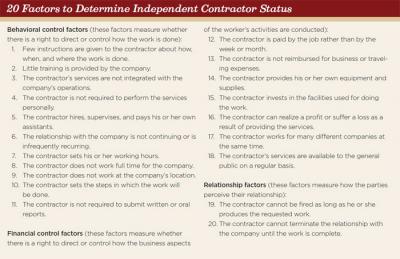

In making the determination whether a worker is an employee, examiners usually apply a 20-factor test (see sidebar). In determining whether the right of direction and control exists, no one factor is necessarily controlling, and the relative importance of any one factor may vary depending on the occupation under consideration.

The IRS considers three aspects of control when determining whether a business employs a worker:

- behavioral control

- financial control

- the relationship of the parties

Behavioral control is shown by facts regarding the right to direct or control how the worker performs the specific tasks for which he or she is hired.

Financial control is shown by facts regarding a right to direct or control the financial aspects of the worker’s activities. These include whether there is a significant investment by the worker, whether the worker’s success depends on entrepreneurial skill, and whether the worker makes his or her services available to the relevant market in addition to the service recipient.

The relationship of the parties is generally shown by the parties’ agreements and actions with respect to each other, paying close attention to those facts that show not only how they perceive their own relationship, but also how they represent their relationship to others.

The application of the factors outlined in the sidebar is illustrated by a couple of recent cases.

In Atlantic Coast Masonry Inc. (Tax Court, 2012), the IRS reclassified masons as employees and charged the construction company $700,000 in back taxes. Although the workers provided their own tools and were free to seek employment as masonry workers with other businesses, the business always delivered instructions to the workers prior to commencement of the project and many workers worked exclusively for the construction company. The workers also worked a required eight-hour day; they could be fired at will; and they received weekly cash payments based on their productivity.

In Donald G. Cave (Tax Court, 2011), a law firm failed in its attempt to reclassify its legal associates and clerks as independent contractors. The law firm argued it did not have sufficient control over the associates’ and clerks’ work. The IRS prevailed by focusing on the investment in facilities, permanence of the relationship, and the integral role the associates played in the law firm’s business.

3 Steps for Business Owners

These cases illustrate that how the business owners and contractors characterize the relationships does not necessarily control the IRS’s viewpoint. A document cannot change the substance of the arrangement completely. There are three important steps business owners can follow to make sure the independent contractor relationship is honored.

First, define the relationship in a written business document. Address the 20 factors item by item. Many business owners may not want to give up the control of the worker, but to obtain the savings, it may be necessary.

Second, using the 20 factors as a guide, structure the work relationship in such a way that it is an independent contractor relationship.

Third, comply with the IRS’s reporting requirements, primarily the issuance of Form 1099s for independent contractors.