Journal of Financial Planning: December 2018

Moshe A. Milevsky, Ph.D., is a tenured professor of finance at the Schulich School of Business and part of the graduate faculty in mathematics and statistics at York University in Toronto.

Disclosure: The author is a member of the board of directors of CANNEX Financial, which operates in the annuity business and provided some of the data discussed. The views expressed here are his own and do not reflect the position of this journal, York University, or CANNEX.

Acknowledgment: The author thanks Lowell Aronoff, Gary Baker, Alexa Brand, Faisal Habib, Gary Mettler, Edna Milevsky, Alireza Rayani, and A.J. Tell for comments on prior versions.

Editor’s note: This commentary is being published in lieu of a research paper this month. It is the author’s personal views; it was not peer reviewed by the Journal’s peer review board. It was accepted for publication by the editorial staff.

As investment-focused financial advisers develop an appreciation for the important role of annuities in mitigating longevity risk, I continue to stumble upon annuity myths that permeate the retirement income dialogue. Fables are repeated with increasing frequency in the professional and public arena. And, while the world is awash in so-called fake news, if advisers view themselves as fiduciaries, then getting the facts straight should be more than an exercise in intellectual virtue. This article draws upon a quarter century of my own research to clarify what I see as common misconceptions around annuity benefits as well as unfair condemnation. The appendix at the end of this article provides support for a number of issues noted. — M.M.

Allow me to begin with a personal story that provides a typical example of widespread annuity ignorance. In 1993, when I was a graduate student in finance and economics, I wrote a term paper that eventually became a published (and co-authored) study titled “How to Avoid Outliving Your Money.” In that article I used some fancy mathematics to investigate how a retiree, defined as someone trying to target and maintain a desired standard of living (not necessarily the 4 percent rule), should allocate a portfolio between investments such as stocks and bonds.

The key message in the article—which in the early 1990s might have appeared novel—was that retirees should continue to maintain a substantial exposure to stocks well into their 70s and 80s because they were likely to live a long time. And, as everyone knows by now, in the long run (professor Jeremy Siegel is the messiah and) stocks will outperform bonds. Technically speaking, in the article I “proved” that the lifetime ruin probability (LRP) was minimized with more stocks, assuming certain analytic mathematical properties, etc. Anyway, that was the main thesis and like all budding academics in training, I took the message on the road.

In one of my very first public forays, I presented the above-mentioned paper to a large conference of insurance industry specialists and actuaries. The response from the crowd was tepid at best, partially because of my naiveté and inexperience communicating with non-academic audiences. At the time, 25-year-old me believed that a room full of 50-year-old financial service professionals in Orlando (or maybe it was Las Vegas) would be nothing short of thrilled to experience a compendium of equations early in the morning after a night of social cocktails.

When I completed my symphony of Greek and the patient moderator asked the audience for questions, there weren’t any from the floor. I remember this part clearly, because after a long and awkward silence, someone finally lumbered over to the microphone and declared in a crisp British accent: “Young man, if what you are trying to do is reduce the probability of running out of money, then you should consider purchasing an annuity from a life office.” There were murmurs, nods of approval, and even a few giggles from the audience. At the time, my own mumbled response was that well, thank you for the great comments about annuities, and that I would have to look into that annuity thing carefully and thank you again, blah, blah.

You see, back in 1993, I had absolutely no idea how a life annuity provided insurance against outliving wealth. It wasn’t part of my curriculum in business school or the established cannon in graduate courses on econometrics, microeconomics, and derivative pricing. Even to this day, a proper understanding of annuities is not part of the formal educational curriculum for most college and university students in finance, economics, and business.

Now, fast forward 25 years later, and I personally have atoned for my own ignorance but continue to come across large groups of educated professionals with CFPs, CFAs, MBAs, and Ph.D.s who, similar to mini-me, don’t quite understand the role of annuities in ensuring you have enough money for the rest of your life. So, I have decided to distill my observations into one document and hope this will be useful to financial advisers, planners, and wealth managers who are trying to help their clients manage the financial life cycle, longevity risk, and its associated expenses. Instead of selecting random myths to debunk, this article is a collection of insights, views, and observations on the topic of annuities from my perch in the ivory tower.

Observation No. 1: There’s Nothing to Hate or Love About Annuities

You might have seen the full-page newspaper advertisements funded by a well-known and high-profile registered investment adviser, Ken Fisher, claiming that he hates annuities and that everyone else should hate them too. In fact, there is an amusing video on YouTube where Fisher is interviewed by fellow billionaire Steve Forbes on the topic of annuities (watch it here: youtu.be/o8pEE6XTLV4). When Forbes asks our protagonist why he hates annuities, his response is, “What’s not to hate?” and they both share a laugh. Of course, being billionaires, neither of them really need to worry about retirement income or having enough money to last for the rest of their life. Most Americans don’t have that luxury.

In contrast to both of them (on many levels), I am occasionally classified as a “lover” of annuities or positioned as a previous “hater” who saw the light and converted to become a lover, perhaps while strolling on the Road to Damascus from Jerusalem. To set the record straight, I love my wife, my four precious daughters, and my mother (well, now that she has retired and moved south). But, I neither love nor hate annuities. They aren’t a type of music or literary genre that one can develop strong feelings for or against. Rather, annuities are a type of financial plus insurance instrument (I like the word finsurance) that is absolutely necessary for managing your retirement plan, no different than car insurance for driving a car, or other insurance and warranties.

Do you love the extended warranty on your home furnace? How about your life insurance? Do you love that piece of paper? To repeat, I like my furnace and love my life—but need to protect the financial implications of losing either.

Here are the cold facts. According to LIMRA, in 2017 Americans purchased a total of $200 billion in annuities, which coincidentally was the same amount of money they spent (or invested, depending on your definition) on auto insurance premiums, according to insurance analysts at NASDAQ. Now yes, the $200 billion figure is less than half of the $476 billion invested in exchange-traded funds (ETFs), but an ETF can’t solve all your retirement income problems, and a $200 billion market is worthy of your attention.

Why all the hate and vitriol, then? Well, in Fisher’s and Forbes’ defense, perhaps they associate annuities with opaque products, high ongoing fees, commissions, and infinite surrender charges. Many of those are odious to me as well, and I detest paying for things I don’t need, but it has nothing to do with annuities. It’s about compensation for selling product. And, as far as I’m concerned, as long as it’s disclosed in a pedagogically sound manner so the buyer understands what they are paying and why, then let the free market prevail in the race between commissions and fees.

More often than not, though, people don’t understand what they are paying for service, how an annuity works, or the combined nature of what it’s trying to achieve. This “ignorance” quite naturally leads to caution and trepidation. Also, please remember that most insurance premiums are meant to be wasted. You don’t want to put in a claim on your car insurance, home insurance, or even life insurance. So, what seems like an excessive fee to you might be an insurance premium to me. Bottom line: get the facts first then form an opinion.

Observation No. 2: Not All Annuities Are Really Annuities

With the emotional stuff out of the way, allow me to move on to linguistics. In my professional opinion the word annuity is quite meaningless, perhaps no different from the word fund.

Think about it this way: what are your thoughts about funds? Do you like funds? Do you own any funds? How much of your money is allocated to funds? Well, replies someone with even a remedial understanding of finance, what type of fund? Hedge funds? Venture capital and private equity funds? Exchange-traded funds? Mutual funds? The word annuity without a descriptor isn’t informative. There are life annuities and term-certain annuities, fixed annuities and variable annuities, immediate annuities and deferred (aka delayed) annuities, etc.

To the essence of this article, when an academic financial economist such as myself talks about the benefit of annuities, he or she is likely referring to a very simple product, quite similar to a coupon-bearing bond. The transaction works as follows. You fork over (invest,

deposit, allocate) $100,000 or $500,000 or $1 million to an insurance company. It then promises to pay you a monthly income of $500, or $2,500, or $5,000 for the rest of your life. The basic (academic) annuity differs from a coupon-bearing bond in that there is no maturity or terminal date when the principal is returned.

You never get the original deposit back, but the payments will last as long as you live. That could be 10, 20, 30, or even 100 years if you believe the optimists (or lunatics, depending on your point of view).

Financially speaking, the original investment is amortized and spread evenly over your lifetime. I like to explain it as having a mortgage on your house that never matures. As long as you are still alive, you have to make mortgage payments to the bank. No matter how much you have already paid, it’s never over. This sounds horribly usurious and unappealing, but reverse the image and you will understand how the basic (academic) annuity works. The insurance company has to make payments to you forever; it never ends as long as you are alive. That’s something I can live with.

Now, these basic (academic) annuities aren’t supposed to offer refunds, liquidity, or the ability to change your mind later. Nor do they offer much to your heirs in the form of a so-called death benefit. In fact, if you get hit by a bus tomorrow the money is gone. In exchange for this “risk” you get to enjoy your old age knowing that regardless of how long you (or perhaps jointly with a spouse) live, the check will be in the mail.

Speaking of old and academics, the first economist to advocate and rigorously argue for their use in retirement portfolios was a very distinguished scholar by the name of Menahem Yaari, writing in the 1960s when he was a professor at Yale and Stanford University. Another scholar who deserves credit is Solomon Huebner, who was a professor (nicknamed Sunny Sol) at Wharton. He wrote about and lectured on the benefit of (eventually, at retirement) converting whole life insurance policies into life annuities, back in the 1930s and 1940s. My point is that annuities have an academic pedigree.

This sort of basic (academic) annuity can also be described as a pension, quite justifiably, inasmuch as it’s purchased around the age of retirement and performs the same function. Think of buying more units of Social Security (you can’t) or defined benefit pension (growing extinct). I prefer the phrase income annuity and will stop referring to them as academic or basic.

I am willing to bet my Ph.D. that if these income annuities were the only annuities that most real people purchase, Ken Fisher and Steve Forbes wouldn’t dare belittle them. But, the fact is, these basic income annuities rarely sell and aren’t very popular. In fact, the same academics who—one could say—“love” them have employed teams of psychologists to explain the “hate.” I’ll get to that later, but first some industry background.

There are more than 1,000 life insurance companies in the U.S. that could potentially manufacture and issue income annuities, but the vast majority of sales are via approximately 25 carriers. The average premium for an income annuity in 2017 was $136,000 according to the LIMRA Secure Retirement Institute (referenced earlier). The average age of an income annuity buyer was just shy of 72 (an age I’ll return to later), although 20 percent of sales were to individuals under the age of 65. The gender composition of a typical buyer was balanced 50/50, and half of U.S. sales were in qualified retirement plans, which means that income was taxed as ordinary (I’ll also return to that later.)

Although an income annuity is manufactured by an insurance company, the transaction itself is intermediated via a sales channel, which—according to the CANNEX/LIMRA Secure Retirement Institute 2016 Income Annuity Buyer Study—could be a career agent (32 percent of sales), independent agent (8 percent), broker-dealer (41 percent), bank (17 percent), or direct response (2 percent). It’s interesting to note that the average premium and investment into an annuity were twice as large in the full-service national broker-dealer channel ($164,000) versus the direct response channel ($80,000).

Finally, the CANNEX/LIMRA study also shows that although 81 percent of income annuity sales guarantee a lifetime of income, 41 percent of sales included a period certain, 32 percent included a cash refund, and 10 percent included an installment refund. These guarantees cost extra and/or reduce the lifetime payout. Only 12 percent of income annuity sales were pure life only. Indeed, the product that most financial economists promote (and write about) aren’t very popular. See Table 1 for more on this emerging trend.

Notice how in late 2011, approximately 25 percent of income annuity sales (or more accurately, annuity quotes) were life-only annuities that offered no additional guarantees or death benefits. It provided the highest level of income for any given initial investment or deposit. In contrast, by the middle of 2018, that fraction had declined to 14 percent, and the majority of income annuity sales (which aren’t that large to begin with) were associated with a cash or installment refund at death. Nothing is free in life or even death, and these additional guarantees dilute the embedded mortality credits. You get less.

Now, I don’t have a degree in psychology, but I will venture a guess that people have very good reasons for not liking the simple life-only income annuity beloved by most academics. Retirees aren’t quite rational; they don’t always do what’s in their best interest; they want the ability to change their mind, leave money for their heirs, etc.

The old income annuity, which has been around since the 17th century, is perceived as a straightjacket. So, insurance companies in the last century have come to the rescue of consumers by offering—and promoting—guarantees and refunds. Many have gone a step further and created annuity-like investment products that offer a modicum of a pension but aren’t quite the longevity insurance nirvana endorsed by scholars. These would be variable annuities (VAs) with guaranteed lifetime withdrawal benefits (GLWB), guaranteed minimum income benefits (GMIB), equity-indexed annuities (EIA), fixed annuities, structure annuities, etc.

Some of these “annuities’’ grow and mature into a true income annuity. Others have the option to be converted into an income annuity. A few have absolutely nothing to do with either pensions or lifetime income, but for whatever legal and regulatory reason get to masquerade as annuities. These products have many complex (yes, I admit) features and can be quite confusing to understand unless you happen to have a Ph.D. in finance, economics, or mathematics. This isn’t the time or place to explain every annuity product currently available or review the history of their mispricing and the annuity blowups (and bad risk management) around the year 2008. Don’t get me started on annuity buybacks, which have recently hit the Canadian marketplace.

These complex annuities might be the source of the vitriol and fear alluded to earlier. And, to be honest, excess complexity in financial and insurance products is usually associated with shrouding of fees and commissions. In the VA + GLWB case, the shrouding blinded many of the insurance actuaries, and ironically, many were mispriced in favor of the consumer (full disclosure: I happily purchased some of these “underpriced” annuities).

Again, my objective here isn’t to offer an encyclopedic overview of all the different types of annuities available—a universe that continues to grow with every application and filing with the insurance commissioners—but rather to alert readers to appreciate the fact that not all annuities are annuities. More importantly, if you hear of, or plan to quote, research in support of the benefit of annuities, please appreciate that my fellow academics never liked or endorsed products that charge hundreds of basis points in fees for little in benefits.

Don’t stop at the word annuity. Dig deeper. What does it do for your client, exactly?

Observation No. 3: You Might Already Own Too Many Annuities

The U.S. National Academy of Sciences in Washington, D.C. publishes recommended dietary allowances and reference intakes on their website. In addition to the usual vitamins A, B, D, K, etc., they also recommend a number of elements for daily intake. For example, a typical 50-year-old male should consume 1,000 milligrams of calcium (for females it is 1,200) per day, 700 milligrams of phosphorus, and 11 milligrams of zinc (for females 8 is enough.) There are other interesting elements on the list, such as copper, iron, magnesium, and manganese.

Think about the following “allocation” question: should you include phosphorus or zinc supplements in your “portfolio” of daily pills? Well, if your regular diet consists of plenty of peas (phosphorus) and shellfish (zinc), then you are probably consuming more than the recommended milligrams per day. There’s no need for more. But if you don’t (or can’t) enjoy those foods, or other dishes heavy in phosphorus and zinc, you should consider supplements. But remember, 700 milligrams of phosphorus per day is a good idea, 7,000 is unhealthy and 70,000 will incinerate your internal organs and kill you.

My point?

The role of annuities in the optimal retirement portfolio is similar to the role of these minerals and elements. A well-balanced daily diet includes a cocktail of copper, iron, phosphorus, and zinc. All diversified retirement portfolios should consist of some cash, stocks, bonds, real estate, health insurance, long-term care insurance, and some—but not too much—annuities. I like to think of it as a retirement cocktail.

So, if your client already is entitled to annuity income, they don’t need any more. If they receive substantial Social Security payments relative to their income needs, or a corporate defined benefit (DB) pension, they might be over-annuitized. That group of clients (which may be larger than you think) do not need any more. If a couple is receiving $50,000 a year in Social Security benefits and they only have $100,000 in savings, why in the world should it be allocated to (more) annuities? Too much annuities—that is, income that dies with you—could kill you.

Observation No. 4: Warren Buffett Doesn’t Need an Annuity for Longevity Insurance

Consistent with the zinc and phosphorus analogy, some individuals don’t need any annuities because of the nature of their personal balance sheet. They may have very little Social Security or DB pension income (relative to their financial needs), but they have substantial assets and will never exhaust their money, even if they live forever. The longevity of their portfolio is infinite.

I suspect Warren Buffett would be in that category. He is a reasonable man with a savvy eye for investments. As the chairman and CEO of an insurance company, I’m sure he would understand the benefits of risk management. But I doubt he would be interested in purchasing an annuity, because he doesn’t face longevity risk exposure. To be clear, I’m not saying he already has enough zinc and copper. His body doesn’t need it.

Here is a story I enjoy telling undergraduate students when I give my standard lecture on the benefits of insurance:

During the habitable months of the academic year I teach in Toronto on the north shore of Lake Ontario where many people own boats moored at various marinas. A few years ago, I received a phone call during dinner from a salesperson representing one of the large P&C insurers in town. It was close to the end of the year and he wanted to know if I was interested in purchasing boat insurance (which, like car insurance, is mandatory for boat owners). He mentioned that the company was having a sale—something to do with capital and reserves changes—and if I acted within the next 24 hours I could save 40 percent on premiums compared to regular rates.

I thanked him for the call (well, not really), but informed him that I didn’t own a boat and had no interest in purchasing a boat and to please remove me from the calling list. Undeterred, this energetic fellow went on with his script and said something to the effect of “the offer will expire tomorrow,” this was a unique opportunity to take advantage of insurance that was on sale, etc.

“But, I don’t own a boat,” I said again, baffled that this call hadn’t ended yet. On he went. I wondered, what did he want me to do? Buy a boat so I could benefit from cheap insurance? No boat. No need for boat insurance.

Corny (yet true), but it is the essence of a problem with all insurance that also applies to annuities. Many people just don’t need more annuities. Yes, they could be cheap, on sale, and the deal of the century, but if you don’t face the underlying risk, don’t bother getting coverage.

The analogy may not be precise because everyone owns at least a small longevity raft, but they also have government (Social Security) insurance to protect them. So, who falls in the “no boat” category? Well, when someone who is already retired informs me that they are very comfortable financially and could sustain their lifestyle for another 50 years of retirement (albeit rare), they are not a candidate for an annuity—at least from a risk management perspective. They don’t own a “longevity risk” boat and therefore don’t need the coverage. Figure 1 offers another perspective on who needs income annuities and the associated insurance.

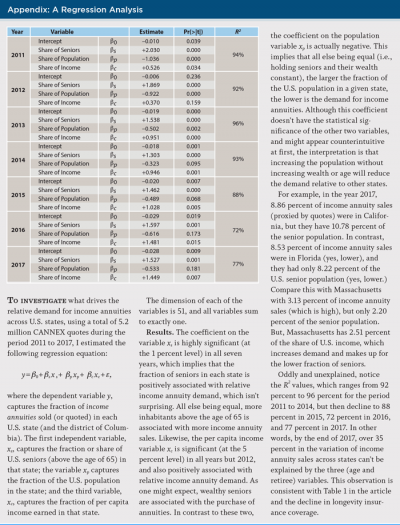

Imagine two single 65-year-olds. One is a relatively unhealthy male with an optimistic life expectancy of 15 years. The other is a healthy female who can expect 30 more years of remaining life. Assuming all else is equal on their personal balance sheet (although it never is), who benefits more from the longevity insurance inside income annuities? As you can see from Figure 1, the individual volatility of longevity (iVoL) for the unhealthy male is 60 percent, which is double the 30 percent number for the healthy female. I would argue that he needs the annuity more. It’s not about how long you think you will live. It’s about the risk.

Of course, cold, rational insurance protection is just one dimension of the demand for income annuities. There is also the emotional argument, popular as of late, well founded in the school of behavioral finance economics. However, I worry that approach leads to a slippery slope of justification for almost any financial product that makes your client “feel good.” More importantly, there might be excellent legal and regulatory reasons for owning annuities—namely their ability to shelter assets from creditors—but that has nothing to do with longevity risk and pooling. I suspect many bankrupt ex-millionaires and even billionaires wish more of their assets had been allocated to insurance and annuity products. These ancillary benefits bring me to my next point.

Observation No. 5: Taxes Disfigure Everything, Including Annuities

By construction, almost every annuity involves handing over a sum of money to an insurance company in exchange for the return of those funds over a drawn-out period, often decades. In between the “in” (investment, premium) and “out” (cash flow, lifetime income) the money sits inside the insurance company’s accounts and earns interest and investment returns. This gestation and growth period is important to governments, not only individuals, because someone, somewhere has to pay taxes on those gains. These gains aren’t easy to identify or compute, which leads to another host of annuity considerations and mathematical headaches.

Different countries and jurisdictions have their own unique tax treatment for this (imputed, assumed) growth. Some offer a rather liberal treatment and a very “good deal”—for example, the U.S. decision to approve the Qualified Longevity Annuity Contract (QLAC). Other countries impose disadvantageous and unfair distortions. The tax treatment of the longevity insurance can kill the appeal. Canada is an example of a jurisdiction in which the current tax treatment of deferred income annuities renders them unviable. So, you have a boat in Lake Ontario, need protection, but it’s financially better and suitable to set sail without insurance.

Most of the early academic articles and papers in the annuity economics literature focused exclusively on the benefits of risk-pooling and longevity insurance, and for better or worse shied away from commenting on—or even knowing about—the tax implications, including premium tax and exclusion/inclusion ratios.

As most financial advisers in the U.S. are well aware, if the annuity is sitting inside a tax shelter, such as an IRA or 401(k), the tax treatment is quite simple: all the money you receive (or extract) as cash flow over the course of your life is treated as ordinary income, since you never paid tax on the funds. But if the funds are outside a shelter (i.e., non-qualified) the situation is more complicated and can either help or hinder your tax position depending on specifics.

In other words, the annuity’s unique tax treatment might increase its appeal as an investment instrument for individuals who benefit from the shelter (today), regardless of their insurance attributes. For others, the ordinary income classification of the lifetime of cash flows might actually hurt. Again, it depends on specifics. Generally speaking, I would argue that annuities are better located in tax-sheltered (qualified) retirement accounts because the money is already “tax damaged” and you will be paying (high) ordinary interest income on the gains and withdrawals. But there are exceptions.

In sum, don’t confuse the economic and insurance properties of the annuity with its tax characteristics. You might hate or love the tax treatment, but that has nothing to do with longevity risk and pooling.

Observation No. 6: Annuities and Seniors Go Together

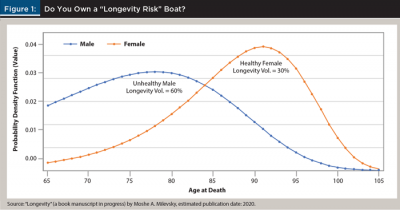

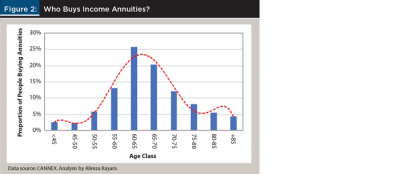

The financial and insurance products I’m discussing here, whether it be a variable annuity, deferred income annuity, or indexed annuity, is likely to be purchased by someone who is older, perhaps senior, and sadly with an increased likelihood of dementia and Alzheimer’s. These aren’t purchased by savvy, 25-year-old millennials. Figure 2, based on more than 5.2 million income annuity sales (or quotes) and described fully in the appendix at the end of this article, provides a graphical illustration of the typical buyer over the life cycle.

Now, to this point in the narrative, I have refrained from presenting any hard-core statistical analysis since most of the points didn’t require such firepower, but the obvious fact is that income annuities are more likely to be purchased by wealthy seniors. The appendix to this article (see page 55) describes a statistical analysis that indicates that between 75 percent and 95 percent of the variation in income annuity sales across the U.S. can be explained by the fraction of the state population above the age of 65 and their relative income. In other words, if you tell me how many seniors you have in a particular region and how wealthy they are, and I can “forecast” annuity sales with 75 percent to 95 percent accuracy. In fact, increasing the size of the population and holding the fraction of seniors constant actually reduces annuity demand. It’s really all about relatively old people.

What all of this means is that yes, these buyers need more protection than most and there should be a heightened regulatory awareness of the transaction, regardless of the type of annuity. It shouldn’t be as easy to buy an annuity online as it is to purchase a stock, bond, or Bitcoin for that matter. These decisions (and purchases) are quite difficult to reverse or undo, which is exactly why it makes sense to have a financial adviser as intermediary in between the manufacturer and end-user. To all you 20-year-old developers contacting me with ideas on how to create an app that sells annuities and longevity insurance directly to the public, please stop for now.

Likewise, I have little sympathy for advisers who lament an ever-growing regulatory burden placed on annuity sales relative to other financial products such as ETFs or mutual funds. They expect one-click annuity shopping on their internal firm’s platform. The compliance folks tell me this will never happen. Indeed, please take a careful look at the audience at your client appreciation events. They need more protection than average.

Observation No. 7: True Annuities Have Many Academic Fans

For readers interested in more than my personal opinions, the sidebar to this commentary (see page 52) is a curated list of 20 scholarly articles and some books that could form the basis of any formal university course on annuity finance and economics. I have assigned most of them as readings to my own graduate students. Although many of these articles are written in the language of mathematical probability, their main message is quite clearly English: annuities are worth considering.

The last article on the alphabetical list was written by the previously mentioned Menahem Yaari in the mid-1960s and should probably be listed first on any formal list. He created the foundation for the field of life cycle economics (and much of the financial planning profession) by “proving” that for rational individuals who were trying to “smooth’’ consumption over their life cycle, there was no other investment asset that could outdo the annuity. Why? The mortality credits and risk pooling. This insight might not seem terribly deep to the typical financial adviser, but in an academic’s ivory tower world, it was like uniting quantum physics and gravity in one big theory.

Other noted academic economists who have written about the important role of annuities in the optimal portfolio and have extended the Yaari model are Zvi Bodie, Jeffrey Brown, Shlomo Benartzi, Peter Diamond, Laurence Kotlikoff, Robert Merton, Olivia Mitchell, Franco Modigliani, James Poterba, William Sharpe, Eytan Sheshinski, and Richard Thaler. Any educated reader of the financial literature and self-respected investment adviser will recognize most of the names on this list, which includes quite a few Nobel laureates.

My point isn’t to convince you with credentials or blind you with science, but rather to alert you that in addition to their many other contributions to modern finance and economics—for which they are better known—all have written favorably about the role of annuities. They recognized long ago that many Americans would face a retirement income crisis as they approach the latter stages of the human life cycle. Your clients need the supplementary phosphorous and the zinc due to an ingrained dietary deficiency. Take the time to acquaint yourself with the science—not the marketing—before forming your own opinion.

A Personal Note

To end on a personal note, I have had the pleasure and honor of calling Menahem Yaari a mentor as well as a family friend. In his mid-80s and retired after teaching economics at Hebrew University, he is also the past-president of the Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities. I recently had the opportunity to have an informal lunch with him in Jerusalem where, after the usual pleasantries, the conversation turned to economics. Although he wrote the previously noted landmark piece over 50 years ago and has since published many important articles in other areas of mathematical economics and decision theory, he never returned to write about annuities. Some might call it a one-hit wonder, but what a song! My understanding is that he claimed, when asked, that he didn’t think he had much to add to that classic 1965 paper.

When I asked him during our recent lunch what he was thinking about these days (a standard question in our field), he mentioned that now that he was retired, he developed an appreciation for the importance of retiring slowly, versus ceasing work all at once. It’s quite reasonable advice and should resonate with anyone who counsels retirees. Here is his advice: work part-time, never exit the labor force irreversibly, and always maintain a connection to your profession.

We chatted on and I inquired whether this retirement observation was about economics or more of a personal, psychological reflection. His reply, after some thought, was that it likely meant people should also purchase their annuities slowly, versus all at once. And, he was convinced that even without behavioral and psychological considerations, a “neo-classical model of dynamic utility maximization” would lead to gradual annuitization. Ergo, annuities shouldn’t be purchased in one large irreversible transaction. Well, I nearly choked on my hummus as the implication dawned on me.

A follow-up paper? Stay tuned, there might be a sequel to the most famous (1965) academic annuity article ever written. For the time being, the sidebar contains the prerequisites.